1904 Cambridge Springs International Chess Congress

The 1904 Cambridge Springs International Chess Congress was the first major international chess tournament in America in the twentieth century. It featured the participation of World Champion Emanuel Lasker, who had not played a tournament since 1900 and would not play again until 1909. After the tournament Lasker moved to America and started publishing Lasker's Chess Magazine, which ran from 1904 to 1907. However, that was not the only chess magazine spawned by the tournament. The Daily Bulletins produced by Hermann Helms proved so popular that Helms started the American Chess Bulletin as a direct consequence of the tournament. Volume 1, Issue 1 of the magazine was devoted to Cambridge Springs. Helms was somewhat more successful than Lasker as a publisher and American Chess Bulletin would be edited and published by Helms from 1904 until his death in 1963. The surprising upset victory of Frank Marshall marked his rise to prominence in American chess and he would eventually reign as champion of the United States for twenty six years.

Cambridge Springs 1904 marked the end of Harry Nelson Pillsbury's chess career. He would not play another tournament before his death in 1906 at the age of 33.

Background

A small town in northwestern Pennsylvania, Cambridge Springs seems like an unlikely location to hold an international chess tournament. However, back in the early 1900s Cambridge Springs was a flourishing resort town due to a couple geographic oddities. The primary factor was location. At first glance nothing seems remarkable about the town, but in fact it is located on the Erie Railroad line, halfway between New York and Chicago, which made it an ideal stopover location for railway patrons. The secondary factor was the local mineral springs which were visited by numerous people seeking to improve their health.

In 1895 William D. Rider Jr. started construction on what he hoped would be the greatest hotel between Chicago and New York City. The mammoth hotel was not completed until 1897. When finished, the hotel featured over five hundred rooms in a seven-story structure spanning five acres. Features included a theater for five hundred, where the chess tournament was held, a ballroom, a solarium, two gymnasiums, bowling alleys and an indoor pool. The hotel grounds were equally impressive, featuring a nine-hole golf course and a man-made lake.[1]

Rider was a successful publicist for his hotel, and the chess tournament of 1904 was an outgrowth of those efforts. Over two hundred reporters from around the world were present at the Rider Hotel. Financed primarily by Rider and the Erie Railroad Company, the tournament received additional support from Professor Isaac Leopold Rice as well as by selling tournament bulletins to chess clubs around the country.[2] It was originally intended that the chess tournament be a yearly affair; however, Rider died in 1905 and the prospect of future tournaments died with him.

Cambridge Springs was the most important chess tournament that took place in the year 1904.[3] It was the first major international tournament in America since the Sixth American Chess Congress of 1889.[4] There would not be another tournament of the same stature in America until the New York 1924 chess tournament. In 1998 the U.S. Chess Championship returned to Cambridge Springs and the tournament was held in one of the few hotels remaining from the railroad resort era, the Riverside Inn.

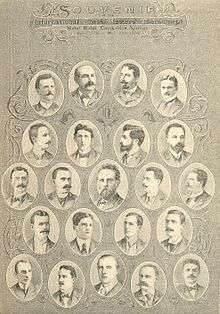

Participants

(From top to bottom:) H. Helms, H. Cassel, J. Redding, W. Van Antwerp, C. Schlechter, F.J. Marshall, Em. Lasker, M. Chigorin, J. Mieses, G. Marco, I. Rice, D. Janowsky, J.W. Showalter, A.B. Hodges, A.W. Fox, H.N. Pillsbury, T.F. Lawrence, W.E. Napier, R. Teichmann, H. Ridder, E. Delmar, J. Barry

All of the world's top players were invited to the tournament. Géza Maróczy was unable to attend due to his career as a mathematics teacher. Tarrasch, having finished behind Lasker at Hastings and Nuremberg, was carefully avoiding tournaments in which Lasker was participating.[6] In fact the two would not face each other in a tournament until the St. Petersburg 1914 chess tournament, eighteen years after their last meeting at Nuremberg.

While most of the players were seasoned international veterans, four of the competitors, Barry, Fox, Hodges and Lawrence, participated in an international tournament for the first time at Cambridge Springs.[7]

The players could be roughly divided into two groups, eight Europeans and eight Americans.

The Europeans:

- Emanuel Lasker 35, Berlin – The reigning World Chess Champion

- Mikhail Chigorin 53, St. Petersburg – Champion of Russia

- Dawid Janowski 35, Paris – Born in Poland, eventually became a French citizen

- Carl Schlechter 29, Vienna – Drew a World Championship match with Lasker in 1910, but Lasker retained the title

- Georg Marco 40, Vienna – Editor of the Wiener Schachzeitiung

- Jacques Mieses 38, Leipzig – Long career in Chess as a player, organizer and writer

- Richard Teichmann 35, London – Born in Germany, living in London as a language teacher, blind in his right eye

- Thomas Lawrence 33, London – Six-time champion of the London Chess Club

The Americans:

- Harry Pillsbury 31, Philadelphia – Winner of the greatest tournament of the nineteenth century, Hastings 1895

- Frank Marshall 26, Brooklyn – Living in England for the two years prior to the tournament

- Jackson Showalter 43, Georgetown, KY – Six-time United States Chess Champion

- Albert Hodges 42, Staten Island – Three-time New York State Champion

- John Barry 31, Boston – Champion of New England

- William Napier 22, Pittsburg – Born in England, moved to America at the age of five

- Albert Fox 23, New York – Brooklyn Chess Club champion

- Eugene Delmar 63, New York – Four-time New York State Champion

The Europeans and Marshall would all arrive in America on a single steamship, the S.S. Pretoria.

Main tournament

The tournament started on April 25, 1904, and ended on May 19, 1904. It was a single-round-robin tournament where each player would play one game against the other players, for a total of fifteen games. Games were played on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday. Wednesday was for adjourned games and Saturdays were for Rice Gambit consultation games. Games started at 10:00 am and played until 3:00 pm and then continued at 5:00 pm to 7:00 pm if necessary. The time control was 30 moves in 2 hours, then 15 moves per hour. There was a "grandmaster draw" rule that prohibited draws of less than 30 moves, unless the draw was forced.[8]

Janowski, Marshall and Teichmann all started the tournament very strongly. After six rounds Janowski led with 5½ points, followed closely by Marshall and Teichmann with 5. Teichmann became ill and would only score an additional 1½ points in the remaining nine rounds.[9] Marshall and Janowski continued their torrid pace through the ninth round where they both had eight points, followed by Lasker in third with 6½. In the tenth round however, Janowski started to falter and lost two games in a row, including one to Fox.

Going into the 15th and final round Marshall was in first place with 12 points, but he was only one point ahead of Janowski, who in turn was only one point ahead of Lasker. Marshall played black against Fox who was up a pawn after 20 moves. However, Fox quickly blundered a rook and Marshall won.[10] Meanwhile, Janowski and Lasker were playing against each other for second place. Janowski, with a one-point lead, only needed a draw with the white pieces to clinch the second prize. Janowski launched a very spirited attack against Lasker's king, which was stuck in the center of the board. Lasker was up to the challenge though, and built a defense that turned back Janowski's attack and eventually won the game.[11]

Marshall finished first, undefeated with 13/15, and with his last round victory Lasker tied Janowski for second place with 11/15.

Tournament crosstable

| # | Player | Country | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Frank Marshall | USA | X | 1 | ½ | ½ | 1 | 1 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 | $1000 |

| 2 | Dawid Janowski | POL | 0 | X | 0 | ½ | ½ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | $450 |

| 3 | Emanuel Lasker | GER | ½ | 1 | X | ½ | ½ | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 11 | $450 |

| 4 | Georg Marco | AUS | ½ | ½ | ½ | X | ½ | ½ | 1 | 0 | ½ | 1 | 0 | 1 | ½ | ½ | 1 | 1 | 9 | $200 |

| 5 | Jackson Showalter | USA | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | X | ½ | 1 | 1 | 1 | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | 8½ | $165 |

| 6 | Carl Schlechter | AUS | 0 | 0 | 1 | ½ | ½ | X | 0 | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | 1 | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | 7½ | $67.50 |

| 7 | Mikhail Chigorin | RUS | ½ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | X | 1 | ½ | 0 | 1 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7½ | $67.50 |

| 8 | Jacques Mieses | GER | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ½ | 0 | X | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ½ | 1 | 0 | 7 | |

| 9 | Harry Pillsbury | USA | 0 | 0 | 1 | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | 0 | X | 1 | ½ | 0 | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | 7 | |

| 10 | Albert Fox | USA | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | X | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6½ | |

| 11 | Richard Teichmann | GER | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ½ | 0 | 0 | ½ | 0 | X | ½ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6½ | |

| 12 | Thomas Lawrence | UK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ½ | 0 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 0 | ½ | X | 1 | ½ | 0 | ½ | 5½ | |

| 13 | William Napier | USA | ½ | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | 0 | 0 | 0 | ½ | 1 | 0 | 0 | X | 1 | 1 | ½ | 5½ | |

| 14 | John Barry | USA | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | 0 | 0 | 1 | ½ | 0 | X | 0 | 1 | 5 | |

| 15 | Albert Hodges | USA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ½ | 0 | 1 | 0 | ½ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | X | 0 | 5 | |

| 16 | Eugene Delmar | USA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ½ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ½ | ½ | 0 | 1 | X | 4½ |

In addition $700 was distributed among the non-prize winners, in accordance with the number of points scored by each player.

Brilliancy prize

.png)

The Baron von Rothschild contributed $100 for a brilliancy prize. Initially it was voted to split this into two prizes of $60 and $40.[12] However, in the end four prizes were actually awarded:

First prize ($40) was won by Schlechter for his defeat of Lasker. Second prize ($25) went to Napier for his win against Barry. Third and fourth prizes ($35) were split by Janowski for his victory over Chigorin, and by Delmar for his victory over Hodges.[13]

The game that won third place, Chigorin vs. Janowski, was not one of the games initially submitted for the prize.

Ten games were submitted for the prize (winners are in bold):[14]

- Barry vs. Napier

- Hodges vs. Delmar

- Lasker vs. Showalter (draw)

- Barry vs. Teichmann

- Janowski vs. Napier

- Mieses vs. Janowski

- Marshall vs. Pillsbury

- Janowski vs. Marshall

- Schlechter vs Lasker

- Lasker vs Napier (submitted by both players, Napier thought this the best game he ever played despite the loss[15] )

Pillsbury's revenge

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

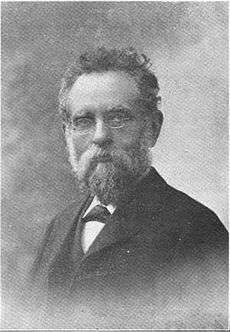

One of the most famous games of the tournament was Pillsbury's revenge against Lasker. This game is actually more famous for the folklore that surrounds it than for the game itself.

The story starts in St. Petersburg, 1896 when Lasker beat Pillsbury in a magnificent game which won the brilliancy prize. Immediately after the game Pillsbury is convinced his 7th move was a mistake and an alternate move would have led to an advantage.[16] Dr. J. Hannak, Lasker's biographer, describes Pillsbury's preparation:[17]

That very night, after his shattering defeat, Pillsbury sat down for many hours, analysing his new idea and satisfying himself that indeed it would have given him the advantage. During the next weeks and months he burned a good deal more midnight oil in the privacy of his room, analysing his new variation as thoroughly as he knew how; but he did not tell anybody about it. Since the opening concerned was a variation of the Queen's Gambit very popular in those days, Pillsbury had countless opportunities to give his new line the practical test; but he would not waste his precious discovery on any of the small fry, thereby divulging his great secret; he would spring that surprise on no one less than Lasker.— J. Hannak, Emanuel Lasker

Finally, eight years after his initial defeat, Pillsbury has the opportunity to unveil his improvement against Lasker.

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. Nf3 c5 5. Bg5 cxd4 6. Qxd4 Nc6 (see diagram) 7. Bxf6! gxf6 8. Qh4 dxc4 9. Rd1 Bd7 10. e3 Ne5 This knight move is a mistake. Tarrasch recommends (10...f5 11.Qxc4 Bg7 12.Qb3 Bxc3+ 13.Qxc3 Qa5) while modern engines prefer (10...f5 11.Qxc4 Qb6 12.Rd2 0-0-0) 11. Nxe5 fxe5 12. Qxc4 Qb6 13. Be2 A positional pawn sacrifice that Black probably should have declined with Rc8. 13... Qxb2 14. 0-0 Rc8 15. Qd3 Rc7 16. Ne4 Be7 17. Nd6+ Kf8 18. Nc4 Qb5 This move is given incorrectly as Qb4 by some sources.[18] 19. f4 exf4? 20. Qd4! White now has a large advantage. 20... f6 21. Qxf4 Qc5 22. Ne5 Be8 23. Ng4 f5 24. Qh6+ Kf7 25. Bc4 Rc6 26. Rxf5+ Qxf5 27. Rf1 Qxf1+ 28. Kxf1 Bd7 29. Qh5+ Kg8 30. Ne5 1–0 Black will get mated in six moves at most.

Cambridge Springs Defense

The Cambridge Springs Defense of the Queen's Gambit Declined takes its name from this 1904 tournament. It was played in three games: Marshall–Teichmann, Hodges–Barry and Schlechter–Teichmann. The results were not good as Black only scored a single draw and two losses.

Despite these results and the fact that the variation did not truly originate at Cambridge Springs, the name Cambridge Springs Defense is still used today to refer to this variation.[19]

Rice Gambit Tournament

Along with the main tournament a special Rice Gambit consultation tournament[20] was contested on three consecutive Saturdays, April 30, May 7 and May 14. This is widely attributed to Rice's sponsorship of the main tournament. It is not clear if the players received additional compensation for playing in the Rice Gambit tournament or if it was considered part of their responsibilities for entering the main tournament.

Overall, the Rice Gambit "won" the tournament with a score of four wins, one loss and two draws.

Round one

| White | Result | Black |

|---|---|---|

| Mieses, Lasker, Showalter and Barry | 1–0 | Chigorin, Schlechter and Fox |

| Delmar, Teichmann, Napier and Lawrence | 0–1 | Marco, Pillsbury, Marshall and Hodges |

Round two

| White | Result | Black |

|---|---|---|

| Mieses, Lasker, Showalter and Barry | 1–0 | Delmar, Teichmann, Napier and Lawrence |

| Chigorin, Schlechter, Fox and Janowski | 1–0 | Marco, Pillsbury, Marshall and Hodges |

In the third round the four man teams dissolved and three two man consultation games were played instead.

Round three

| White | Result | Black |

|---|---|---|

| Marshall & Barry | ½–½ | Lasker & Mieses |

| Chigorin & Showalter | ½–½ | Marco & Hodges |

| Schlechter & Teichmann | 1–0 | Delmar & Lawrence |

References

- ↑ Crisman, Sharon (2003). Around Cambridge Springs. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 30–35. ISBN 978-0738513270.

- ↑ Munro, James (Winter 1993). "The Cambridge Springs International Chess Congress, 1904". Western Pennsylvania History: 185.

- ↑ Harding, Tim. "Chess in the Year 1904" (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Hannak, J (1991). Emanuel Lasker. Dover. p. 106. ISBN 0-486-26706-7.

- ↑ Helms, Hermann (October 1904). American Chess Bulletin. 1 (5): 95.

- ↑ Spraggett, Kevin. "Tidbits on Cambridge Springs 1904". SPRAGGETT ON CHESS. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Helms, Hermann (1904). American Chess Bulletin. 1 (1): 27.

- ↑ Helms, Hermann (1904). American Chess Bulletin. 1 (1): 32–33.

- ↑ "The Players". Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ↑ "Fox – Marshall: Cambridge Springs, 1904". Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ↑ "One Hundred Years Ago: Chess in the Year 1904" (PDF). Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ↑ Helms, Hermann (1904). American Chess Bulletin. 1 (1): 33.

- ↑ Wall, Bill. "Cambridge Springs 1904". Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ↑ Helms, Hermann. American Chess Bulletin. 1 (1): 27.

- ↑ Hannak, J. Emanuel Lasker. Dover. p. 110. ISBN 0486267067.

- ↑ Brandreth, Dale (1960). Lasker vs. Pillsbury. p. 63.

- ↑ Hannak, J (1991). Emanuel Lasker. Dover. p. 107. ISBN 0-486-26706-7.

- ↑ Harding, Tim. "Chess in the Year 1904" (PDF). Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ Harding, Tim. "Chess in the Year 1904" (PDF). Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ Helms, Hermann. American Chess Bulletin. 1 (1): 34–35.

Further reading

- Reinfeld, Fred (ed.) (1935). The Book of the Cambridge Springs International Tournament, 1904. Black Knight Press.

- Helms, Hermann (ed.) (1904). The American Chess Bulletin, Vol. 1, No. 1.

- Schroeder, James (1992). Great American Chess Tournaments, Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania, 1904. Chess Digest.

- Panczyk & Ilczuk (2003). The Cambridge Springs. Gambit Publications. ISBN 978-1901983685.

External links

- CAMBRIDGE SPRINGS 1904

- Tidbits on Cambridge Springs 1904

- 1904 Cambridge Springs International Chess Congress

- Cambridge Springs (1904) at Chessgames.com

- Cambridge Springs 1904 at Chess.com