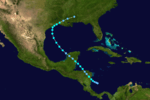

1940 Atlantic hurricane season

| |

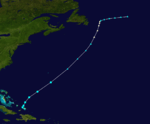

| Season summary map | |

| First system formed | May 19, 1940 |

|---|---|

| Last system dissipated | November 8, 1940 |

| Strongest storm1 | Four – 961 mbar (hPa) (28.38 inHg), 110 mph (175 km/h) |

| Total depressions | 14 |

| Total storms | 9 |

| Hurricanes | 6 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 0 |

| Total fatalities | 71 |

| Total damage | $29.329 million (1940 USD) |

| 1Strongest storm is determined by lowest pressure | |

1938, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1942 | |

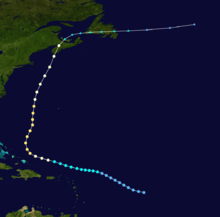

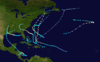

The 1940 Atlantic hurricane season was a generally average period of tropical cyclogenesis in 1940.[nb 1] Though the season had no official bounds, most tropical cyclone activity occurred during August and September. Throughout the year, fourteen tropical cyclones formed, of which nine reached tropical storm intensity; six were hurricanes. None of the hurricanes reached major hurricane intensity. Tropical cyclones that did not approach populated areas or shipping lanes, especially if they were relatively weak and of short duration, may have remained undetected. Because technologies such as satellite monitoring were not available until the 1960s, historical data on tropical cyclones from this period are often not reliable. As a result of a reanalysis project which analyzed the season in 2012, an additional hurricane was added to HURDAT.[nb 2] The year's first tropical storm formed on May 19 off the northern coast of Hispaniola. At the time, this was a rare occurrence, as only four other tropical disturbances were known to have formed prior during this period;[2] since then, reanalysis of previous seasons has concluded that there were more than four tropical cyclones in May before 1940.[3] The season's final system was a tropical disturbance situated in the Greater Antilles, which dissipated on November 8.

All three hurricanes in August brought flooding rainfall to areas of the United States. The first became the wettest tropical cyclone recorded in Louisiana history. The second hurricane impacted regions of the Southeastern United States, producing record precipitation and killing at least 52 people. Despite not making landfall, the third hurricane in August interacted with a stationary front over the Mid-Atlantic states, resulting in localized flooding and thus making the tropical cyclone the wettest in New Jersey history. This hurricane would also be the strongest in the hurricane season, with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 961 mbar (hPa; 28.39 inHg), making it a high-end Category 2 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Activity decreased in September, though a damaging hurricane swept through areas of the Canadian Maritimes, resulting in large crop and infrastructural losses. Two tropical cyclones of at least tropical storm strength were recorded in October, though neither resulted in fatalities. Collectively, storms in the hurricane season caused 71 fatalities and $29.329 million in damages.[nb 3] The 1940 South Carolina hurricane, which swept through areas of the Southeastern United States in August, was the most damaging and deadly of the tropical cyclones.

Storms

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | May 19 – May 25 | ||

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) <996 mbar (hPa) | ||

On May 18, a weak low-pressure area was detected south of Hispaniola.[4] Moving northward, the low became sufficiently organized to be classified as a tropical storm at 1200 UTC on May 19,[3] southeast of Turks Island.[2] At the time, ship observations indicated that the disturbance had a well-defined cyclonic circulation, with the strongest winds situated in the northern semicircle of the cyclone.[2] Continuing northward, the tropical storm gradually intensified and attained maximum sustained winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) by 0000 UTC on May 22.[3] The Belgian ship M.S. Lubrafol recorded a peripheral barometric pressure of 996 mbar (hPa; 29.42 inHg); this was the lowest pressure measured in connection with the storm.[2][4] The following day, the tropical storm temporarily curved towards the east-southeast before recurving back towards a northeast direction.[3][2] At the same time, the storm expanded in size and began to transition into an extratropical cyclone.[4] By 1200 UTC, the cyclone completed its extratropical transition,[3] due to the entrainment of colder air.[4] The remnant system persisted until 0600 UTC on May 27.[3]

Hurricane Two

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 3 – August 10 | ||

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 972 mbar (hPa) | ||

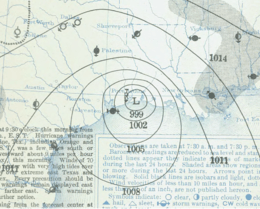

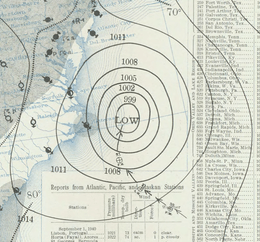

On August 3, an extratropical cyclone developed into a tropical depression off the west coast of Florida.[2][3] Initially a weak disturbance, it moved generally westward, slowly gaining in intensity. Early on August 4, the depression attained tropical storm intensity.[3] Ships in the vicinity of the storm reported a much stronger tropical cyclone than initially suggested.[4] After reaching hurricane strength on August 5 south of the Mississippi River Delta, the storm strengthened further into a modern-day Category 2 hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph and a minimum barometric pressure of 972 mbar (hPa; 28.71 inHg) at 0600 UTC on August 7. The hurricane moved ashore near Sabine Pass, Texas later that day at peak strength.[4] Once inland, the storm executed a sharp curve to the north and quickly weakened, degenerating into a tropical storm on August 8 before dissipating over Arkansas on August 10.[3]

Reports of a potentially destructive hurricane near the United States Gulf Coast forced thousands of residents in low-lying areas to evacuate prior to the storm moving inland.[5][6] Offshore, the hurricane generated rough seas and a strong storm surge, peaking at 6.4 ft (1.95 m) on the western edge of Lake Pontchartrain.[7] The anomalously high tides flooded many of Louisiana's outlying islands, inundating resorts. Strong winds caused moderate infrastructural damage, primarily in Texas, though its impact was mainly to communication networks along the U.S. Gulf Coast which were disrupted by the winds. However, much of the property and crop damage wrought by the hurricane was due to the torrential rainfall it produced in low-lying areas, setting off record floods. Rainfall peaked at 37.5 in (953 mm) in Miller Island off Louisiana, making it the wettest tropical cyclone in state history. Nineteen official weather stations in both Texas and Louisiana observed record 24-hour rainfall totals for the month of August as a result of the slow-moving hurricane.[7][8] Property, livestock, and crops – especially cotton, corn, and pecan crops – were heavily damaged. Entire ecosystems were also altered by the rainfall.[9] Overall, the storm caused $10.75 million in damages and seven fatalities.[7][8]

Hurricane Three

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 5 – August 14 | ||

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 972 mbar (hPa) | ||

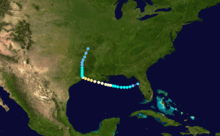

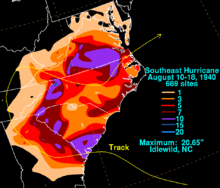

A storm of potentially Cape Verde origin was detected in the Virgin Islands at 1800 UTC on August 5. Initially moving westward, the tropical storm gradually gained in intensity before making a sharp curve towards the north on August 8. The storm continued in a northerly motion before a second curvature brought it in a generally westward direction on August 9. Shortly after, the tropical storm reached hurricane intensity as a modern-day Category 1 hurricane.[3] The hurricane eventually made landfall at peak intensity on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina at 2030 UTC on September 21.[4] At the time, the storm had maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (155 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 972 mbar (hPa; 28.71 inHg), equivalent to a modern-day Category 2 hurricane.[3] Once inland, the tropical cyclone gradually weakened,[2] and recurved northeastward before dissipating over the Appalachian Mountains on August 14.[3]

The hurricane dropped torrential rainfall over the Southeast United States, causing unprecedented devastation in the region.[2] The storm was considered the worst to impact in the region in at least 29 years.[10] Precipitation peaked at 20.65 in (525 mm) in Idlewild, North Carolina.[11] The heavy rainfall caused streams to greatly exceed their respective flood stages, damaging waterfront property.[12] Many of the deaths occurred in North Carolina, where 30 people died.[2] Transportation was disrupted as a result of the debris scattered by the wind and rain. In Caldwell County alone, 90 percent of bridges were swept away.[13] Overall, the storm caused 50 fatalities and $13 million in damages.[2]

Hurricane Four

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 26 – September 2 | ||

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) 961 mbar (hPa) | ||

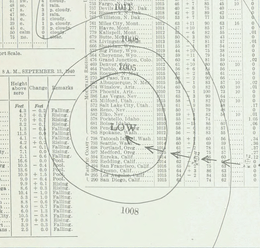

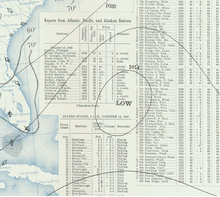

On August 26, a low-pressure area in the open Atlantic Ocean became sufficiently organized to be classified as a tropical cyclone. Moving slowly in a general west-northwest motion, the disturbance intensified, reaching tropical storm strength on August 28 and subsequently hurricane intensity on August 30.[3] The hurricane passed within 85 mi (135 km) of Cape Hatteras before recurving towards the northeast.[4] However, the hurricane continued to intensify, and reached peak intensity as a modern-day Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 961 mbar (hPa; 28.38 inHg), though these statistical peaks were achieved at different times on September 2. Afterwards, the tropical cyclone began a weakening trend as it proceeded northward, and had degenerated into a tropical storm by the time it made its first landfall on Nova Scotia later that day.[3] The storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone the next day while making another landfall on New Brunswick. The extratropical remnants persisted into Quebec before merging with a larger extratropical system late on September 3.[2][4]

Despite not making landfall on the United States,[2] the hurricane caused widespread damage.[14] Extensive precautionary measures were undertaken across the coast, particularly in New England. The heightened precautions were due in part to fears that effects from the storm would be similar to that of a devastating hurricane which struck the region two years prior.[15] Most of the damage associated with the hurricane occurred in New Jersey, where the combination of moisture from the hurricane and a stationary front produced record rainfall, peaking at 24 in (610 mm) in the town of Ewan. This would make the storm the wettest in state history.[16] The resultant floods damaged infrastructure, mostly to road networks. Damage in the state amounted to $4 million.[14] Further north in New England, strong winds were reported, though damage remained minimal.[4] Although the storm made two landfalls in Atlantic Canada, damage too was minimal, and was limited to several boating incidents caused by strong waves.[17] Overall, the hurricane caused $4.05 million in damage, primarily due to flooding in New Jersey, and seven fatalities.[14]

Hurricane Five

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 7 – September 17 | ||

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) <988 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical depression was first detected east of the Lesser Antilles on September 7,[3] though at the time weather observations in the area were sparse.[2][4] The disturbance gradually intensified throughout much of its early formative stages, attaining tropical storm strength on September 10; further strengthening into a hurricane north of Puerto Rico occurred two days later. Shortly thereafter, the hurricane recurved northward, and reached peak intensity the following day as a modern-day Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of at least 988 mbar (hPa; 29.18 inHg).[2][4] The cyclone steadily weakened thereafter before making landfall on Nova Scotia on September 17 with winds of 85 mph (135 km/h).[18] Moving into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence later that day, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. The remnant system curved eastward and passed over Newfoundland before dissipating over the Atlantic on September 19.[3]

While off of the United States East Coast, the hurricane caused numerous shipping incidents, most notably the stranding of the Swedish freighter Laponia off of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina on September 16. Two other boat incidents resulted in two deaths.[19] The hurricane also brought strong winds of tropical storm-force and snow over areas of New England. In Atlantic Canada, a strong storm surge peaking at 4 ft (1.3 m) above average sunk or damaged several ships and inundated cities. In New Brunswick, the waves hurt the lobster fishing industry. In Nova Scotia, strong winds disrupted telecommunication and power services. The winds also severely damaged crops.[18] Roughly half of apple production in Annapolis Valley was lost during the storm, resulting in around $1.49 million in economic losses.[20] Strong winds in New Brunswick caused moderate to severe infrastructural damage, and additional damages to crops occurred there.[18] Overall, the hurricane caused three fatalities, with two off of the United States and one in New Brunswick.[18][19]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 18 – September 25 | ||

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) | ||

A westward moving tropical depression developed in the southwestern Caribbean Sea just west of Bluefields, Nicaragua at 1200 UTC on September 18.[2][3] The following day, the depression intensified into a tropical storm at 0600 UTC.[3] The tropical storm made landfall on the Mosquito Coast of Nicaragua at 1400 UTC, with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h).[3][4] The cyclone weakened to a tropical depression over land, but reintensified back to tropical storm strength upon entry into the Gulf of Honduras on September 20.[3] The cyclone's northwest motion caused it to make a second landfall near the border of Mexico and British Honduras at 0300 UTC on September 21 as a slightly stronger system with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h);[nb 4][4] this would be the storm's peak intensity. Over the Yucatán Peninsula, the tropical storm re-weakened, but later intensified once again once it reached the Gulf of Mexico. In the Gulf, the storm made a gradual curve northward,[3] before making a final landfall near Lafayette, Louisiana at 0900 UTC on September 24 with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1002 mbar (hPa; 29.59 inHg).[2][4] Once inland, the tropical cyclone curved eastward and weakened before dissipating the next day, after becoming absorbed by a frontal boundary.[4]

Upon making landfall, the tropical storm produced strong winds over a wide area. The strongest winds were reported by a station in San Antonio, Texas, which reported 40 mph (65 km/h) winds, far removed from the storm's center; these strong winds were likely due to squalls.[4] Heavy rainfall was also reported, though the rains mainly occurred to the east of the passing tropical cyclone. Precipitation peaked at 10 in (254 mm) in Ville Platte, Louisiana.[16] The tropical storm produced three tornadoes over the Southern United States which collecitvely caused $39,000 in damage and caused two fatalities. Two of the tornadoes formed in Mississippi while one formed in Louisiana. Several other people were also injured by the tornadoes.[22]

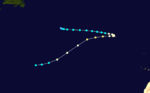

Hurricane Seven

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 22 – September 28 | ||

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) <977 mbar (hPa) | ||

In late September, a tropical wave persisted in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean. The low-pressure area later became sufficiently organized to be classified as a tropical storm at 0000 UTC on September 22.[4][3] The disturbance quickly organized after tropical cyclogenesis, and reached a strength equivalent to a modern-day Category 1 hurricane strength at 1800 UTC later that day.[4] The American steamship Otho encountered the system that day, and reported gale force winds in conjunction with a peripheral barometric pressure of 996 mbar (hPa; 29.42 inHg).[23] The tropical cyclone continued to the east-northeast, where it gradually intensified. At 1200 UTC on September 23, the hurricane attained modern-day Category 2 hurricane intensity with winds of 100 mbar (155 km/h); a peak which would be maintained for at least the following 12 hours.[3] A second steamship, the Lobito, reported hurricane-force winds along with a minimum pressure of 977 mbar (hPa; 28.85 inHg); this would be the lowest pressure measured associated with the tropical cyclone.[23] After reaching peak intensity, the hurricane began a weakening trend, and degenerated to a Category 1 hurricane at 0600 UTC as it passed over the Azores.[3] The following day, the hurricane recurved westward, where it weakened before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone on September 28.[4] This remnant system subsequently dissipated.[3]

As the hurricane passed over the Azores, several weather stations reported low barometric pressures,[23] with the lowest being a measurement of 984 mbar (hPa; 29.06 inHg) on Terceira Island at 0600 UTC on September 25.[4][3] As a result of the impending storm, several Pan Am Clipper flights to the archipelago were suspended for three consecutive days.[24] The maximum reported gust in the Azores was an observation of 65 mph (100 km/h) on September 25. As a result of moving slowly over the islands, torrential rainfall was also reported. At Angra do Heroísmo, 13.11 in (333 mm) of precipitation was reported in a four-day, accounting for a third of the station's yearly average rainfall. Strong storm surge was reported at the same location. The waves swept boats away from the coasts of islands. Further inland, there was extensive damage to homes and crops, though no people died.[23] Despite evidence that the system had distinct tropical characteristics, it was not operationally added to HURDAT.[4]

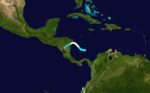

Hurricane Eight

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 20 – October 24 | ||

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) <983 mbar (hPa) | ||

On October 19, a low-pressure area moved into the southwestern Caribbean Sea.[2] The area of disturbed weather quickly became well-organized,[2] and was analyzed to have become a tropical depression at 0000 UTC on October 20.[3] Initially, the tropical cyclone moved very slowly towards the west and then the northwest. Shortly after formation, the disturbance intensified into a tropical storm at 1800 UTC later that day.[3] The S.S. Cristobal provided the first indications of a tropical cyclone in the region, after reporting strong gusts and low pressures north of the Panama Canal Zone during that evening.[2] Continuing to intensify, the storm reached hurricane intensity at 0600 UTC on October 22.[3] Several vessels in the storm's vicinity reported strong gusts and rough seas generated by the storm.[2] Later that day at 1200 UTC, the ship S.S. Castilla reported a minimum pressure of 983 mbar (hPa; 29.03 inHg) near the periphery of the storm. Based on this observation, the hurricane was estimated to have reached intensity at the same time with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).[4] The hurricane subsequently curved west and then southwest, before making its only landfall in northern Nicaragua at 1900 UTC on October 23 at peak intensity. Once inland, the tropical cyclone rapidly weakened over mountainous terrain, and dissipated at 1200 UTC the following day.[3] Reports of damage were limited, though a report stated that considerable damage had occurred where the hurricane made landfall.[2]

Tropical Storm Nine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 24 – October 26 | ||

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) <1007 mbar (hPa) | ||

On October 23, an open trough was centered north of Hispaniola near the Turks and Caicos islands.[4] At 0000 UTC the following day,[3] the area of disturbed weather became organized and was analyzed to have become a tropical storm southeast of Inagua, based on nearby vessel reports. Initially, the storm drifted northward, but later began to accelerate towards the northeast after a roughly 12-hour period.[2][3] At 0600 UTC on September 25, the disturbance slightly gained in intensity to attain maximum wind speeds of 45 mph (75 km/h); these would be the strongest winds associated with the storm as a fully tropical cyclone.[3] A reanalysis of the system indicated that due to a lack of definite tropical features, the storm may have had been a subtropical cyclone. On October 26, the system became increasingly asymmetric and had developed frontal boundaries,[4] allowing for it to be classified as an extratropical cyclone at 0600 UTC that day. Once transitioning into an extratropical system, the storm continued to intensified as it moved northward.[3] On October 27, the system was analyzed to have a minimum pressure of at least 985 mbar (hPa; 29.09 inHg) after passing to the southeast of Bermuda.[3][4] At 1200 UTC later that day, the cyclone reached an extratropical peak intensity with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) just east of Newfoundland. Had the storm been tropical at the time, it would have been classified as a modern-day Category 1 hurricane. Subsequently, the extratropical storm curved eastward, where it persisted before dissipating by 1800 UTC on September 29.[3]

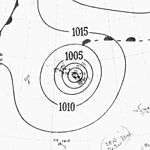

Tropical depressions

In addition to the storms which attained at least tropical storm strength in 1940, five additional tropical depressions were analyzed by the HURDAT reanalysis project to have developed during the season. Due to their weak intensity, however, they were not added to HURDAT.[4] On September 2, a closed low-pressure area was detected in the open Atlantic Ocean southeast of Bermuda and was analyzed as a tropical depression. At the time, the disturbance had a minimum pressure of at least 1015 mbar (hPa; 29.98 inHg). The depression initially moved to the southeast, but later recurved towards the northwest over the next two days.[4] On September 4, the S.S. West Kebar en route for Boston, Massachusetts reported winds of 40 mph (65 km/h),[25] which would be considered as tropical storm-force winds. The depression later moved to the northeast before it was absorbed by a stationary front on September 7. Since there was only one report that the disturbance may have reached tropical storm intensity, it was not included in HURDAT. Later on September 10, a trough was detected in a similar region in the Atlantic where the first depression formed. The trough later became sufficiently organized to be classified as a tropical depression. The cyclone moved slowly to the east and did not further intensify before dissipating on September 13.[4]

On October 7, a large elongated extratropical cyclone extended across the Atlantic Ocean with a pressure of at most 1015 mbar (hPa; 29.98 inHg). The following day, the low-pressure area became more narrow and well-defined, with its central pressure deepening to 1000 mph (hPa; 29.53 inHg). On October 9, the extratropical system was analyzed to have become a tropical depression. The low moved slowly to the northeast and gradually weakened before dissipating on October 10. On October 14, offshore observations indicated that a tropical depression had developed north of The Bahamas. The following day, however, the depression became less defined and degenerated into a trough of low pressure. On October 16, two ships listed in the International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set reported winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) off the coast of North Carolina. However, since these reports occurred in a higher pressure gradient, the system was not included in HURDAT.[4]

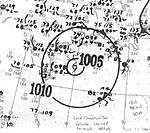

On November 2, a trough of low-pressure was analyzed near the Lesser Antilles. The system moved westward into the Caribbean Sea without much organization. On November 7, the low-pressure area moved south of Cuba and became sufficiently organized to be considered a tropical depression with a pressure of at least 1010 mbar (hPa; 29.83 inHg). The depression moved over Cuba and into the Atlantic, where it dissipated the following day. On November 9, a second system was detected northeast of Bermuda with a pressure of 1005 mbar (hPa; 29.68 inHg), though it remained unclear whether the two systems were related.[4]

Season effects

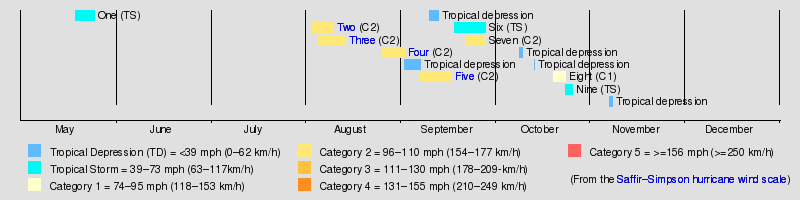

| Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (millions USD) |

Deaths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | May 19 – May 25 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | <995 | None | None | None | |||

| Two | August 3 – August 10 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 972 | Southern United States (Texas, Louisiana) | 10.75 | 7 | |||

| Three | August 5 – August 14 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 972 | Southeastern United States (South Carolina), Mid-Atlantic states | 13 | 52 | |||

| Four | August 26 – September 2 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 961 | Mid-Atlantic states, New England, Atlantic Canada | 4.05 | 7 | |||

| Five | September 7 – September 17 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | <988 | New England, Atlantic Canada | 1.49 | 3 | |||

| Six | September 18 – September 25 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1002 | Central America, Southern United States | 0.039 | 2 | |||

| Seven | September 22 – September 28 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | <977 | Azores | None | None | |||

| Eight | October 20 – October 24 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | <983 | Nicaragua | Unknown | None | |||

| Nine | October 24 – October 26 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | <1007 | None | None | None | |||

| Season Aggregates | ||||||||||

| 9 cyclones | May 19 – October 26 | 110 (175) | 961 | 29.3 | 71 | |||||

See also

Notes

- ↑ An average season, as defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has twelve tropical storms, six hurricanes and two major hurricanes.[1]

- ↑ HURDAT is an official database listing the locations and intensities of Atlantic hurricanes since 1851.

- ↑ All damage totals are in 1940 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

- ↑ British Honduras, formerly a British Overseas Territory, attained its independence in 1981, becoming the country of Belize.[21] The region is referred as British Honduras in the article.

References

- ↑ Climate Prediction Center Internet Team (August 4, 2011). "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Gallenne, J.H. (1940). "Tropical Disturbance of May 18–27, 1940; Tropical Disturbances of August 1940; Tropical Disturbances of September 1940; Tropical Disturbances of October 1940" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 68 (5,8–10): 148, 217–218, 245–247, 280. Bibcode:1940MWRv...68..280G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1940)068<0280:tdoo>2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (pdf) on February 17, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Landsea, Chris; Atlantic Oceanic Meteorological Laborartory; et al. (December 2012). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Gale Blows 90 Miles Per Hour". San Jose News. Port Arthur, Texas. United Press. August 7, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Port Arthur Citizens Flee Coming Storm". The Tuscaloosa News. Port Arthur, Texas. Associated Press. August 7, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Louisiana Hurricane History (PDF). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- 1 2 Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Texas Hurricane History (PDF). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricanes in Louisiana History". thecajuns.com. March 25, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ↑ Ivan Ray Tannehill (1943). Hurricanes. Princeton University Press. pp. 250–251.

- ↑ Roth, David M.; Weather Prediction Center. "Southeast Hurricane - August 10-18 1940". Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. Silver Spring, Maryland: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ↑ Roth, David M.; Weather Prediction Center. "Early Twentieth Century". Silver Spring, Maryland: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Laurelmor and Landslides". WNCSOS. March 5, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "New Jersey Fights To Prevent Disease". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Camden, New Jersey. Associated Press. September 2, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Storm Veers Away From New England". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. September 2, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- 1 2 Schoner, R.W.; Molansky, S.; Hydrologic Services Division (July 1956). "Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances)" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Hurricane Research Project. pp. 262–263. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ Environment Canada (November 12, 2009). "1940-4". Storm Impact Summaries. Government of Canada. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Environment Canada (November 13, 2009). "1940-5". Storm Impact Summaries. Government of Canada. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Hits Steamer; Rescue Ship Draws Near". The Evening Independent. New York, New York. Associated Press. September 16, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricane Diminishes After Causing $1,000,000 Damage in Canadian Area". St. Petersburg Times. Halifax, Nova Scotia. United Press. September 18, 1940. p. 3. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Belize country profile". BBC News. August 2, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ↑ Souder, Mary O. (September 1, 1940). "Severe Local Storms" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 68 (9): 268. Bibcode:1940MWRv...68..268.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1940)068<0268:SLS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Hunter, H.C. (September 1, 1940). "Weather On The North Atlantic Ocean" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 68 (9): 253–254. Bibcode:1940MWRv...68..253H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1940)068<0253:WOTNAO>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ "Clippers Again Are Delayed". New York Times. New York, New York. New York Times. September 27, 1940. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Ocean Gales and Storms". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 68 (9): 255–255. September 1, 1940. Bibcode:1940MWRv...68..255.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1940)068<0255:OGAS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 5, 2013.