Johnson South Reef Skirmish

| Johnson South Reef Skirmish | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sino-Vietnamese conflicts 1979–90 and Spratly Islands dispute | |||||||

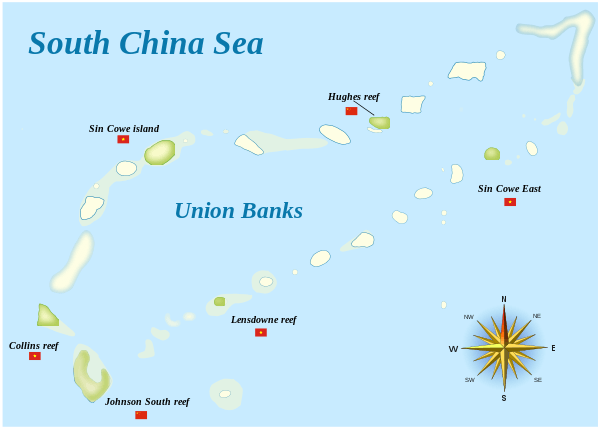

Map of the Union Banks, where the battle occurred | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

502 Nanchong 南充 (Jiangnan Class/065) frigate; 556 Xiangtan 湘潭 (Jianghu II Class/053H1) frigate; 531 Yingtan 鹰潭 (Jiangdong Class/053K) frigate |

HQ-505 (ex Quy Nhon HQ-504) landing craft; HQ-604 armed transporter; HQ-605 armed transporter | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 wounded |

64 killed[1][2]

1 landing craft destroyed | ||||||

The Johnson South Reef Skirmish of 1988 (Chinese: 赤瓜礁海战; pinyin: Chìguā jiāo hǎizhàn; literally: "Naval Battle of Chigua Reef"; Vietnamese: Hải chiến Trường Sa, lit: "Spratly Islands naval battle", or Vietnamese: Hải chiến Gạc Ma, lit: "Johnson South Reef naval battle") was a naval battle that took place between Chinese and Vietnamese forces over Johnson South Reef in the Spratly Islands on 14 March 1988.

Background

During the 14th UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC), it was agreed upon that China would establish five observation posts, including one at the Spratly Islands, for worldwide ocean survey.[4] In March 1987, the UNESCO IOC commissioned China to build the observation post at the Spratly Islands.[4] During the meeting of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, UNESCO in Paris, the Delegate of the People's Republic of China, speaking highly of GLOSS (Global Sea Level Observing System), noted what the PRC considered a few mistakes in the text of Document IOC/INF-663 rev.; for instance, "Taiwan" is listed as a "country" in relevant Tables contained in the Document (Taiwan's official title is in fact the "Republic of China", though within Taiwan and internationally the nation is commonly referred to as "Taiwan, Republic of China", or simply "Taiwan").[5] The scientists from the GLOSS, who did not know that the PRC claims Taiwan is not a "country" or about the territorial disputes in the South China Sea, agreed that China will install few tide gauges on "its coasts" in the East China Sea and on its "Nansha islands" in the South China Sea. Scientists of this era did not know that Taiwan had an island in the Spratly but China (PRC) had none in spite of its claims.[6] In April 1987, after numerous surveys and patrols, China chose the Fiery Cross Reef as the ideal location for the observation post because the unoccupied reef was remote from other claims and it was large enough for the observation post.[4] On the other hand, Johnson South Reef, 150 km East of Fiery Cross Reef, is inside Philippines claimed 200 NM EEZ and close to Sin Cowe Island inhabited by the Vietnamese in Union Banks sunken atoll; clearly a disputed area.[7][8] Between January and February, Vietnamese forces began establishing a presence at surrounding reefs to monitor the Chinese activity.[4] That led to a series of confrontations.[4]

Course

| Part of a series on the |

| Spratly Islands |

|---|

Spratly Islands military occupations map |

| Related articles |

| Confrontations |

| Military occupations |

|

|

China's account

On March 13, the frigate Nanchong detected PAVN Vietnamese transport HQ-604 heading toward Johnson South Reef, transport HQ-605 heading toward Lansdowne Reef, and landing craft HQ-505 heading toward Collins Reef in a simultaneous three-pronged intrusion upon the disputed reefs.[9]

At approximately 07:30 on Johnson South Reef, Vietnamese troops attempted to erect the Vietnam flag on the reef. It was reported that PAVN Corporal Nguyen Van Lanh and PAVN Sub Lieutenant Tran Van Phuong argued over the flag raising with PLA-N sailor Du Xianghou, which led to a pitched battle between the opposing forces on the reef. In response, Vietnamese forces, with naval transport HQ-604 in support, opened fire.[9] PLA-N forces and the frigate Nanchong counter-attacked at 08:47 hours. Transport HQ-604 was set ablaze and sunk.[9]

At 09:15 hours, the frigate Xiangtan arrived at Lansdowne reef and found that 9 Vietnamese marines from transport HQ-605 had already landed. The frigate Xiangtan immediately hailed the Vietnamese and demanded they withdraw from the reef. Instead, the Vietnamese opened fire .[9] The HQ-605 was damaged heavily and finally sunk by the Chinese.[9]

The PLA-N "314" documentary

The PLA-N filmed the skirmish and produced a propaganda documentary called "314" meaning "March 14" in Chinese, which was published on the Internet. It does not show evidence of Vietnamese shots. After the Chinese landing attempt and the Chinese pinnace withdrawal, the Vietnamese soldiers standing in water on the submerged reef, were killed by 37mm AA gunfire from the frigates. Vietnamese soldiers, most of them unarmed,[3][10][11] formed a line on the reef to protect the 3 Vietnamese flags. The PLA-N frigates open fire on the reef's defenders, killing 64 Vietnamese soldiers. Then the PLA-N frigates opened fire on the Vietnamese ships and sunk them.

Vietnam's account

In January 1988, China sent a group of ships from Hainan to the southern part of the South China Sea. This included four ships despatched to the north-west of the Spratly Islands. The four ships then began provoking and harassing the Vietnamese ships around Tizard Bank and the London Reefs. Vietnam believed this battle group intended to create a reason to "occupy the Spratly Islands in a preventive counterstrike".[12]

In response, two transport ships from the Vietnamese Navy's 125th Naval Transport Brigade, the HQ-604 and HQ-505, were mobilized. They carried nearly 100 army officers and men to Johnson South Reef, Collin Reef, and Lansdowne Reef in the Spratly Islands.[10] On 14 March 1988, as the soldiers from the HQ-604 were moving construction materials to Johnson South Reef, the four Chinese ships arrived.[10] The three Chinese frigates approached the reef:

- frigate 502 Nanchong / 南充, (type 65 (Jiangnan class)). Weighs 1,400 tons, equipped with three 100mm guns and eight 37mm AA guns.[13]

- frigate 556 Xiangtan / 湘潭, (Jianghu II class / 053H1). Weighs 1,925 tons, equipped with four 100mm guns and two 37mm AA guns.[14]

- frigate 531 Yingtan / 鹰潭, (Jiangdong class / 053K). Weighs 1,925 tons, equipped with four 100mm guns and eight 37mm AA guns.[15]

Commander Tran Duc Thong ordered Second Lieutenant Tran Van Phuong and two men, Nguyen Van Tu and Nguyen Van Lanh, to rush to the reef in a small boat and the Vietnamese flag that had been planted there the previous day.[10] The Chinese landed armed soldiers on the reef, and the PLA-N frigates opened fire on the Vietnamese ships. Both the HQ-604 and HQ-605 (all armed transports) were sunk.[10] The HQ-505 armed transport was ordered to run aground on Collin reef to prevent the Chinese from taking it.[10]

Vietnamese soldiers, most of them unarmed,[3][11] formed a circle on the reef to protect the Vietnamese flag. The Chinese attacked, and the Vietnamese soldiers resisted as best they could.[10] A skirmish ensued in which the Chinese shot and bayoneted dead some Vietnamese soldiers, but they were unable to capture the flag.[10] The Chinese finally retreated enabling PLA-N frigates to open fire on the reef's defenders. When all of the Vietnamese had been killed or wounded, the Chinese occupied the reef and began building a bunker. Vietnam reported that 64 Vietnamese soldiers had been killed in the battle.[12][16]

Vietnam also accused China of refusing to allow Vietnam's Red Cross ship to recover bodies and rescue wounded soldiers.[17]

Independent account

Cheng Tun-jen and Tien Hung-mao, two American professors, summarized the battle as following: in late 1987, the PRC started deploying troops to some of the unoccupied reefs of the Spratly Islands. Soon after the PLA stormed the Johnson South Reef on 14 March 1988, a skirmish began between Vietnamese troops and PRC landing parties. Within a year, the PLA occupied and took over seven reefs and rocks in the Spratly Islands.[18]

Koo Min Gyo, Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Administration at Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea, reported the battle's course was as follows: On 31 January 1988, two Vietnamese armed cargo ships approached the Fiery Cross Reef to get construction material to build structures signifying Vietnam's claim over the reef.[4] However, the PLA-N intercepted the ships and forced them away from the reef.[4] On 17 February, a group of Chinese ships (a PLA-N destroyer, escort, and transport ships) and several Vietnamese ships (a minesweeper and armed freighter) all attempted to land troops at Cuarteron Reef. Eventually the outgunned Vietnamese ships were forced to withdraw.[4] On 13 and 14 March, a PLAN artillery frigate was surveying the Johnson reef until it spotted three Vietnamese ships approaching its location.[4] Both sides dispatched troops to occupy Johnson Reef.[4] After shots were fired by ground forces on the reef, the Chinese and Vietnamese ships opened fire on each other.[4]

Aftermath

China moved quickly to consolidate its presence. By the end of 1988, it had occupied six reefs and atolls in the Spratly Islands.[4]

On September 2, 1991, China released the nine Johnson South Reef Skirmish Vietnamese prisoners.[3]

In 1994, China had a similar confrontation by asserting its ownership of Mischief Reef, which was inside the claimed EEZ of the Philippines. However, the Philippines only made a political protest, since according to the Henry L. Stimson Center, the Philippine Navy decided to avoid direct confrontation. This was partly based on the Johnson South Reef Skirmish, in which the Chinese had killed Vietnamese troops even though the conflict took place near the Vietnamese-controlled area.[19]

See also

Bibliography

- The South China Sea Online Resource

- Kelly, Todd C. (1999). "Vietnamese Claims to the Truong Sa Archipelago". Explorations in Southeast Asian Studies Vol 3

References

- ↑ Martin Petty; Simon Cameron-Moore. "Vietnam protesters denounce China on anniversary of navy battle". Reuters.

- ↑ TRƯỜNG TRUNG - QUỐC NAM. "Lễ tưởng niệm 64 anh hùng liệt sĩ bảo vệ Gạc Ma". Tuổi Trẻ.

- 1 2 3 4 "Deadly fight against Chinese for Gac Ma Reef remembered". Thanh Nien News. 14 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Koo, Min Gyo (2009). Island Disputes and Maritime Regime Building in East Asia. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4419-6223-2.

- ↑ "IOC. Assembly; 14th session; (Report)" (PDF). 1 April 1987. p. 41.

- ↑ "South China Sea Treacherous Shoals", Far Eastern Economic Review, 13 August 1992: p14-17

- ↑ "Territorial claims in the Spratly and Paracel Islands". GlobalSecurity.org. 11 July 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ "Digital Gazetteer of Spratly Islands". www.southchinasea.org. Archived from the original on 2007-07-17. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- Version dated 19 August 2011 is available at: "Digital Gazetteer of Spratly Islands". www.southchinasea.org. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2014.This list includes the names of all Spratly features known to be occupied and/or above water at low tide.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Secrets of the Sino-Vietnamese skirmish in the South China Sea", WENWEIPO.COM LIMITED., March 14, 1988

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 QUỐC VIỆT (1988-03-14). ""Vòng tròn bất tử" trên bãi Gạc Ma (The immortal circle in the Johnson South Reef)". Tuổi Trẻ. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- 1 2 Mai Thanh Hai - Vu Ngoc Khanh (14 March 2016). "Vietnamese soldiers remember 1988 Spratlys battle against Chinese". thanhniennews.com. Thanh Nien News. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- 1 2 Hồng Chuyên. "Một phần Trường Sa của Việt Nam bị Trung Quốc chiếm như thế nào? (bài 8) (How China took a part of Vietnam's Spratly Islands)". infornet. Infornews. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ↑ "Jiangnan - People's Liberation Army Navy". fas.org. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Jianghu-class frigates - People's Liberation Army Navy". fas.org. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Jiangdong-class Frigate - People's Liberation Army Navy". fas.org. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ H.QUÂN - V.TÌNH - X.HOÀI (2014-03-14). "Tưởng niệm 64 anh hùng liệt sĩ hy sinh bảo vệ đảo Gạc Ma ngày 14-3-1988 (Honoring 64 martyrs who died for protecting the Johnson South Reef in 14-03-1988)". Vietbao. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ↑ Từ Đặng Minh Thu (7 January 2008). "Tranh chấp Trường Sa - Hoàng Sa: Giải quyết cách nào? (Spratly Islands and Paracel Islands dispute: How to resolve?)". Công an Thành Phố Hồ Chí Minh. Công an Thành Phố Hồ Chí Minh Magazine. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ↑ Cheng, Tun-jen; Tien, Hung-mao (2000). The Security environment in the Asia-Pacific. Armonk, N.Y: M.E. Sharpe. p. 264. ISBN 0-7656-0539-2.

- ↑ Cronin, Richard P. (2010-02-04). "China's Activities in Southeast Asia and the Implications for U.S. Interests" (PDF). www.uscc.gov.