1993 Four Corners hantavirus outbreak

.jpg)

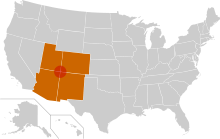

The 1993 Four Corners hantavirus outbreak refers to the first ever known human cases of hantavirus in the United States. It occurred within the Four Corners region of the southwestern part of the country. This region is the geographic intersection where the corners of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona meet. The region is home to the Hopi, Ute, Zuni, and Navajo Nation Indian Reservations.

The cause of the outbreak was found to be a previously unknown hantavirus, which causes a new form of illness known as hantavirus pulmonary syndrome or HPS. The virus is carried by deer mice. The virus was originally referred to as Four Corners virus, Muerto Canyon virus, and Convict Creek virus.[1] It was later named Sin Nombre virus. Transmission to humans was found to be via aerosolized contact with deer mice droppings in enclosed spaces in and around the homes of the victims.

Background

In April, 1993, a young Navajo woman arrived at the Indian Medical Center emergency room in Gallup, New Mexico complaining of flu-like symptoms and sudden, severe shortness of breath. Doctors found the woman’s lungs to be full of fluid. The young woman died soon after her arrival. An autopsy revealed the woman’s lung to be twice the normal weight for someone her age. The cause of her death could not be found and the case was reported to the New Mexico Department of Health.[2]

A month later, a young Navajo man was en route to his fiancée’s funeral in Gallup, when he suddenly became severely short of breath. By the time paramedics brought him to the Indian Medical Center emergency room, he’d stopped breathing and the paramedics were performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The young man could not be revived by doctors and died. The physicians, recalling the similar symptoms and death of the young woman a month earlier, reported his death to the New Mexico Department of Health.[2]

Epidemiology

New Mexico state health officials notified the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Within a week, a task force had formed in Albuquerque that included George Tempest, chief of medicine at the Indian Medical Center. Tempest quickly discovered that five people, including the young man’s fiancée, as well as an Arizona resident, all had experienced the same symptoms and all had died within a six-month period. Tempest learned from the young man's family members that his fiancée had the same symptoms and died on the Navajo Reservation five days earlier. Deaths on the reservations are not reported to the state health department because they are sovereign nations. Tempest had considered plague as the cause because it is endemic to the region. But that had already been ruled out by tests on all the victims. Within a short time, a dozen more people contracted the illness, most of them young Navajos in New Mexico. This included two relatives of the young couple who had died within a week of each other.[2]

Discovery of Sin Nombre virus

News outlets began reporting on the story of a mystery illness causing deaths among young Navajo, often using the term "Navajo Flu". Hearing a news report, a physician notified health officials to say that the illness sounded a lot like hantavirus, which he'd observed in Korea in the 1950s.[3]

The Centers for Disease Control tested for hantavirus even though Asia and Europe were the only documented places where hantavirus had been known to occur. No known cases had ever been reported in the United States. In addition, all the cases in Asia and Europe had involved hantaviruses that caused kidney failure, but never respiratory failure. The testing revealed a previously unknown hantavirus which was eventually named Sin Nombre virus, or No Name virus. The disease became formally known as hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, or HPS.[4][5]

Several theories were advanced to explain the emergence of the new virus. These included increased contact between humans and mice due to a 'bumper crop' in the deer mouse population. Another theory was that something within the virus had changed, allowing it to jump to humans. A third theory was that nothing had changed, that hantavirus cases had occurred previously, they just had not been properly diagnosed before. This last theory turned out to be the correct one when it was discovered that the first known case had actually occurred in a 38-year-old Utah man in 1959.[5]

Like the Korean virus, Sin Nombre virus did not spread person to person. Instead, transmission occurred from aerosolized mouse droppings in enclosed spaces in and around the homes of victims. All the Four Corners victims were found to have high infestations of deer mice in and around their homes.[5]

Course of illness and death rate

Doctors reported that all patients had mild flu-like symptoms such as malaise, headache, cough, fever, with a sudden onset of pulmonary edema necessitating ventilators and finally death. From April to May 1993, there were 24 reported cases. Twelve of those people died, or 50% mortality rate. Of the 24 cases, 14 were Native Americans, nine were non-Hispanic white and one was Hispanic.[6]

Early cases in Tribal lore

Navajo leaders reported similar outbreaks in 1918, 1933, and 1934. Navajo tribal stories identified mice as sources of bad luck and illness back to the 1800s.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Hjelle, B. et al., "Emergence of Hantaviral Disease in the Southwestern United States," Western Journal of Medicine, 1994 161 (5): 467-473.

- 1 2 3 "Death at the Corners". DiscoverMagazine.com. 1993-12-01. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ↑ "Doctors still trying to diagnose mysteries of hantavirus - Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ↑ BioScience: November 2002/Vol. 52. No. 1) 989.

- 1 2 3 "CDC - History of Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS) - Hantavirus". Cdc.gov. 2012-08-29. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ↑ CDC, "Outbreak of Acute Illness-Southwestern United States, 1993," Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, June 11, 1993, 42 (22): 421-424

- ↑ Fimrite, Peter (2012-09-23). "Hantavirus outbreak puzzles experts". SFGate. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hantavirus. |

- Sloan Science and Film / Short Films / Muerto Canyon by Jen Peel 29 minutes

- "Hantaviruses, with emphasis on Four Corners Hantavirus" by Brian Hjelle, M.D., Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, University of New Mexico

- CDC's Hantavirus Technical Information Index page

- Viralzone: Hantavirus

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Bunyaviridae

- Occurrences and deaths in North and South America