71st Regiment of Foot, Fraser's Highlanders

The 71st Regiment of Foot was a regiment of infantry raised in 1775, during the American Revolution. The unit served in both the Northern and Southern Campaigns, and participated in many major battles including the Battle of Long Island (1776), the Battle of Brandywine (1777), Capture of Savannah(1778), Battle of Briar Creek (1779), the Siege of Savannah (1779), the Siege of Charleston (1780), the Battle of Camden (1780), Guilford Courthouse (1781), and the Battle of Yorktown (1781). The regiment was disbanded at the end of hostilities in 1783.

The regiment was unofficially known as Fraser's Highlanders and is referred to both in contemporary writings, including correspondence by regimental soldiers, and in later historical accounts. The official title of the regiment was always simply "71st Regiment of Foot" in the Annual Army List. When the regiment arrived in America in the summer of 1776, the two battalions were split up to form three smaller provisional battalions of about 500 men each. The two Grenadier Companies joined the Grenadier Company of the 42nd Highlanders to form the 4th British Grenadier Battalion.

Raising The 71st Regiment

When war erupted with the American Colonies, Britain's recruiting efforts became crucial to her ability to wage the war and many Scottish people flocked to the cause. In 1778, some 15,000 men were enlisted into the British Army. Two-thirds of them were from Scotland. The 71st Regiment of Foot (1775–1783) was created from among these recruits.

Upon the realization that war with the American Colonies was imminent, the British Army was expanded from its 70 numbered Regiments of Foot. The first new regiment was raised by Colonel Simon Fraser and designated the 71st Regiment of Foot. King George III bestowed the honour of being the first new regiment to Fraser because of the outstanding service of another regiment of Fraser’s Highlanders, the 78th Regiment (1753–1763), in the Seven Years (or French and Indian) War. The earlier unit’s service in Canada was widely lauded and equal hopes of success were held for the "new" Fraser’s Highlanders. In point of fact, however, the Regiment was never officially called the Fraser’s Highlanders; instead it was always the 71st Regiment of Foot.

Colonel Simon Fraser was the chieftain of the Frasers of Lovat. He raised the 78th Regiment of Foot for the French and Indian Wars. He regained the lands forfeit in 1746, but did not accompany his Regiment to America. He died a Lieutenant General in 1782.

The Regiment was officially raised at Stirling Castle and in April 1776 moved to Glasgow. Several clan chiefs supported Fraser in building the regiment. Six of these served as officers. In short order, the 71st exceeded their recruiting needs and the unit embarked for America overstrength, including a large number of combat-proven officers from the old 78th Fraser’s Highlanders.

Organization

While typical regiments of the time had 1080 men in 10 companies, many sources indicate that the 71st were unusual as their organization numbered 2340 all ranks. The Regiment was organized into the 1st and 2nd battalions. The Regiment was later divided into three battalions during the New York campaign of 1776.

The 71st Regiment joined the Black Watch (42nd Regiment of Foot) in Glasgow in April 1776. The presence of the two regiments in Glasgow doubled the Highland population of the city. The 71st was well received in Glasgow according to historian John S. Keltie:

Their conduct was so laudable and exemplary as to gain the affections of the inhabitants, between whom and the soldiers the greatest cordiality prevailed.

Before the 71st Regiment left Glasgow for Greenock and America the unit’s overage was discovered and some of the unit ordered left behind in Scotland. This overage was probably identified by the Inspector General during the review of the Regiment prior to departing Glasgow. It is thought that many soldiers may have stowed away on the transports to avoid being left behind.

At about the same time, a company of 120 men raised on the forfeited estate of Captain Cameron of Lochiel mutinied. The company enlisted with the understanding that Captain Cameron would serve as their commander; when Cameron fell ill and did not arrive in Glasgow the company refused to leave the city until he arrived. The mutiny quickly ended when Simon Fraser convinced the men that a friend and relative of Captain Cameron, Captain Cameron of Fassifern should command the company instead. Captain Cameron died while traveling to join his unit.

Colonel Fraser did not accompany the new 71st Regiment of Foot when it set sail for Boston Harbor.

Uniforms of the Fraser Highlanders

Little is certain about the regiment’s dress. Archaeological research revealed buttons and a bonnet badge from the Regiment, but little else.

The Frasers were originally outfitted in proper Highland Military uniforms since surviving records indicated "no breeches" when the regiment was formed. Kilts were probably of standard military tartan officially known as 'Government', commonly called "Black Watch" today. Pipers may have worn another tartan since they were not officially on the Army's rolls.

Enlisted men wore brick-red coats and officers and non-commissioned officers wore scarlet. Uniform coats had white facings and the buttons were numbered 71. The lace for the button holes was white with a red worm for enlisted and corporals; sergeants wore white tape while officers had silver.

The cartridge box badge, commonly misidentified as a bonnet badge, was a brass roundel with the cross of St. Andrew surrounded by an outer band with the words Quicquid Amt Facere Aut Pati (Whatever is to be performed or endured). In the centre of the Roundel is a Thistle and below it is the number 71. In an Inner circle around the Thistle is the phrase: Nemo Me Impune Lacesset (No one assails me with impunity). The type of headgear the unit soldiers wore was a blue bonnet with a diced band. This was adorned with a regimental button, silk cockade and ostrich feathers.

The American climate and lack of re-supply may have had an adverse effect on men wearing the kilt during the first year, since there is no mention of the kilt in historical records after that. First-hand accounts confirm that by the time of the Southern Campaign the unit’s soldiers wore trousers. Typically, white linen trousers were worn in the summer while brown wool trousers were worn in the winter months. Regimental records indicate that large numbers of these tightly fitted trousers were ordered in the Southern Campaign.

Deployment to America

The crossing to America proved dangerous; in the spring and summer of 1776, when the 42nd and 71st Regiments travelled to America, American privateers were regularly successful at intercepting British merchant shipping. In May, the convoy transporting the Regiment was separated in a storm and two transports carrying men of the 71st were later attacked. HMS Crawford carrying men of the regiment, their wives, and children was captured by the USS Andrew Doria. Later, the British vessel HMS Cerberus recaptured the Crawford, though the Crawford was later once again captured by the Americans.

In June 1776, six ships carrying 71st soldiers were attacked with mixed results by Americans. The Anne with the 1st Battalion's light infantry and Captain Hamilton Maxwell was captured by the schooners USS Lee, USS Lynch, and USS Warren. HMS George, carrying Archibald Campbell and Major Menzies was captured in Boston Harbor by the USS Franklin and the same three American ships that attacked Anne. Likewise, the Brig HMS Annabella, with a company of the 1st battalion under Captain George Mac Kenzie was attacked and run aground in Boston Harbor. The final loss occurred when the Lord Howe with a grenadier company of the 2nd Battalion was captured by seven vessels.

Not all the American attacks were successful, however. The Mayflower with Captain Angus MacIntosh and the Mermaid with Captain Peter Campbell both evaded capture when attacked. In the Mayflower encounter, according to eye-witness accounts, the privateers were repulsed by the 71st. The Mayflower attacked with cannon and when its ammunition gave out, the Americans closed to board the British vessel. But upon seeing the 71st ready for a fight, the privateers broke off the action.

It is thought by some that the losses in Boston Harbour resulted from poor communication. When the British evacuated the city, they could not communicate this change to all the ships headed there. Later, unaware that the city had been abandoned by the British, several ships sailed into the harbour and were attacked by American land and naval units. When the 71st Regiment was attacked, they put up a stiff resistance, but the transports were trapped within an American stronghold. During the fighting, Major Menzies and several others were killed and the rest became prisoners. Many of these prisoners were later exchanged in time to participate in the Southern Campaign.

The Northern Campaign

The 71st Regiment of Foot joined General William Howe at Staten Island in July 1776. Even though the 71st had never drilled, it was placed on line almost immediately. Major Menzies was supposed to lead the drill but he was killed in Boston Harbour and the rapid pace of events in the summer of 1776 virtually eliminated any training time.

On 1 August 1776, General Clinton arrived with reinforcements and the army of 25,000 was divided into seven brigades and a reserve for operations against Brooklyn. The 71st was placed in the 7th Brigade with some Loyalist and Hessian units. The 71st's Grenadiers were placed in the reserve along with the 33rd and 42nd Regiments.

The Americans under Major General Israel Putnam placed 10,000 men in defensive positions along Brooklyn Heights, and another 5,000 defended New York and the Hudson River. General Howe intended to sweep Long Island free of Americans and envelop the city from the east and north, beginning with Brooklyn.

The British moved into position by sea and on 22 August 1776. The British force landed at Gravesend Bay, Long Island. Light American resistance was quickly swept aside and the Americans retreated to Flatbush, burning everything they could in the retreat. Lord Cornwallis pursued the Americans near Utrecht and Flatlands.

Over the next few days, the American strengthened their positions along high ground while the British reconnoitred the defences. The American right was defended by Major General William Alexander aka "Lord Stirling" in a good position, but the left under Major General John Sullivan failed to cover the Jamaica Road. This left the extreme left American flank open.

On 26 August 1776, Hessian units approached Flatbush and engaged General Sullivan's forces with artillery to hold the Americans in place while the main British force flanked General Sullivan along the Jamaica Road. The main force set out on its flanking march at 9:00 pm with the 71st, 17th Light Dragoons, Light Infantry, Grenadiers, the 1st Brigade, and 14 guns. Two hours before sunrise, the pass on the road was captured and the British force immediately moved on. The British main force then envelopment and General Sullivan's main force was nearly encircled and forced into retreat.

With General Sullivan’s force out of the way, the British left under Major General James Grant moved against General Stirling’s better position. The engagement lasted for four hours but was eventually flanked by Lord Cornwallis and organized resistance ended.

Reports of bravery among soldiers of the 71st Regiment were noted in the battle while the Regiment lost three men killed and 11 wounded (two sergeants and nine men).

After the battle, General George Washington reinforced the defences at Brooklyn, but on the night of 29 August 1776, he withdrew the entire force to New York.

On 15 September 1776, British warships sailed up the Hudson River to Bloomingdale and up the East River to Turtle Bay. Fire from these vessels scattered American defenders, and the British ground forces landed to complete the encirclement of New York. The two thousand Americans remaining at Harlem retired to Harlem Heights and won a small action there the next day.

The next operation for the 71st Regiment was at Fort Washington on 16 November 1776. Participating with the regiment were the 4th, 10th, 15th, 23d, 27th, 28th, and 52nd Regiments and a force of Hessians.

Fort Washington

Fort Washington was an oblong fortification three miles (5 km) long by one-and-a-half mile wide with five bastions along the Hudson River. At dawn on 16 November 1776, a naval and artillery bombardment began, and the infantry moved into place. The Hessian column moved against the north from Kingsbridge. The second column, commanded by Lord Cornwallis, moved against the east from Harlem Creek. The third began a feint south of Lord Cornwallis, and below them, the fourth under Lord Percy (including the 71st Regiment) moved forward. The advance was slow because of the heavy American resistance, the difficult terrain, and the strength of the fortifications, but the 42nd eventually broke through the defences which effectively routed the defenders. The British lost 458 and the Americans over 3,000 killed, wounded, or captured.

Fort Lee

Four days later, on 20 November 1776, Lord Cornwallis led 4,500 men to surprise Fort Lee. A deserter spoiled the surprise attack, however, and Major General Nathanael Greene withdrew his 2,000 men to Hackensack, New Jersey, where they joined General Washington. Six days later, the 71st Regiment joined Lord Cornwallis as reinforcements.

Winter 1776-77

On 28 November 1776, as General Washington’s army left New York for Hackensack, Lord Cornwallis attacked his rear guard and continued the pursuit to Trenton, New Jersey. At Trenton, the Americans crossed to safety.

General Howe ordered the British into winter quarters on 14 December 1776. The 71st Regiment wintered in Amboy, New Jersey and played no part in the winter operations in New Jersey even though they were quartered in the area. Likewise, early operations of 1777 were limited to skirmishing actions and the expeditions against Willsborough and Westfield which did not involve the regiment.

Brandywine

The Regiment did, however, participate in the Battle of Brandywine. General Howe's plan called for the capture of Philadelphia while simultaneously tying up American forces that might hinder General Burgoyne’s operations in upstate New York. To confuse the Americans, General Howe chose naval movement for the manoeuvre which placed several American cities at risk, including Boston, Albany, and Philadelphia. The 71st sailed for the Chesapeake Bay on 23 July 1777.

The British landed near Elkton, Maryland on 25 August 1777 and moved north towards Philadelphia in two columns. The 71st joined the first column under Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen along with Hessians, two brigades with four regiments each, the Loyalist Queen's Rangers, a squadron of dragoons, and several guns.

General Washington's forces tailed the British after the landing, skirmishing at Elkton, Wilmington and Cooch's Bridge, with the main Continental defence taking place along the Brandywine halfway between Elkton and Philadelphia on good defensive ground. The main defence was placed at Chadd's Ford and was supported with very strong defensive works.

On 11 September 1777, General Howe sent the second column under Cornwallis north to the American right where it flanked the Americans. Knyphausen’s force, using both battalions of the 71st to protect his flanks, drove directly to Chadd’s Ford and began an artillery bombardment which pinned General Greene’s forces in place.

General Sullivan’s force was pushed aside by Cornwallis which then threatened Greene’s force holding along Brandywine Creek, and Greene moved to counter Cornwallis, forced to defend against both him and Knyphausen. The 1st battalion of the 71st spearheaded Knyphausen’s attack across the ford. General Washington withdrew the Americans, while Greene’s force held off the British until after dark.

Autumn 1777

The 71st Regiment remained with this force until November, but records do not indicate participation in the Battles of Paoli Tavern (night of 20 September 1777), or Germantown (4 October 1777), or in the capture of Philadelphia (25 September 1777). The 71st sailed back to New York in November 1777 where they received 200 recruits from Scotland and 100 men from hospitals.

Burgoyne's expedition

A detachment of 71st Regiment men under Captain Colin MacKenzie supported General John Burgoyne’s operations along the Hudson River in 1777, which were intended to sever the New England colonies from the Mid-Atlantic. The 71st men led the taking of Forts Clinton and Montgomery on 6 October 1777. The 71st men, along with the 26th and 63rd Regiments and a squadron of dismounted dragoons and Hessians, moved to the front of the forts from the river while the 52d and 57th Regiments flanked the positions and attack from the rear. Both forts were simultaneously attacked with bayonets at about 4:30 pm, routing the defenders. The detachment did not participate at Saratoga.

Several sources indicate that a third battalion of the regiment was raised in May 1777 for use in that year’s campaigning, however there is mixed evidence to support this claim. It is more likely that the existing two battalions were divided to create a temporary third battalion.

1778-1779

The 71st Regiment of Foot spent 1778 under Lord Cornwallis in operations in New Jersey, but there is no record of the unit participating in major activities during that period.

Grenadier company

At the end of 1778, the 71st Regiment of Foot departed New York for Savannah but their Grenadiers, which had fought apart from the rest of the regiment since arriving in America, were left behind. When the regiment departed, the Grenadiers remained in the Northern Theater, where they were eventually stationed at Stony Point, New York.

In July 1779, the British captured the fortification at Stony Point. A 600-man garrison, including the 71st's Grenadiers, was left to defend it but on the night of 15 July 1779, Brigadier General Anthony Wayne attacked and recaptured the fort. Wayne's disciplined light infantry force advanced in two columns down the Stony Point peninsula. Between the two larger forces was a minor one to draw British attention. Sentries detected the Americans as they approached the fort, and the general engagement ensued, lasting only thirty minutes. With the entire British force taken prisoner, the operations of the 71st Regiment of Foot in the Northern Campaign came to an end.

The Southern Campaign

The 71st now became involved in the Southern Theatre, where it spent the remainder of the war.

On 26 November 1778, both battalions of the 71st Regiment of Foot (under Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell), two Hessian and four Provincial Infantry regiments, and some artillery set sail from New York for Savannah. They arrived on 24 December and crossed the sand bar into the Savannah River three days later. In the days before the major landing, Campbell captured several Americans and gathered intelligence to improve his understanding of American forces in the area.

First actions

After crossing the bar, Lieutenant Colonel Campbell moved his transports up the Savannah River to within two miles (3 km) of Savannah where they landed unopposed at Girardeau's Plantation (also called Brewton's Hill) on 29 December 1778. The light Infantry under Captain Cameron landed first, followed by the first division (1st Battalion 71st Regiment, New York Volunteers and the 1st Battalion DeLancey's Brigade with two guns) under Lieutenant Colonel Maitland. The forces quickly moved inland along the causeway that led from the Plantation inland toward Girardeau’s Bluff. At the plantation on the bluff, an American force had prepared for defence. Captain Cameron's light infantry advanced to the buildings. Leading the advance was a corporal and four soldiers. A sergeant and 12 men flanked the buildings and the remainder of the company advanced behind the lead group. The Americans allowed the 71st men to come within 100 yards (91 m) of the buildings and then opened fire. With the first American shots, the two groups rushed the buildings, taking them in about three minutes. Captain Cameron and three other ranks were killed in the action.

Advance on Savannah

American defences quickly stiffened, however, and with less than the half force landed, Campbell's advance was halted about one-half mile from Savannah. The American General Howe established his defensive line astride the road to Savannah with his front covered by a stream. The right flank was protected by a wooded marsh and the left by rice-paddies. American artillery was located in the centre of the line. The defence, however, was incomplete, for Howe had failed to protect a road which ran through the swamp on his right. Lieutenant Colonel Campbell learned of this road from a slave and quickly dispatched a flanking force.

At about 2:00 pm, the British were deployed with the Light Infantry on the (British) right and the 1st Battalion of the 71st and the Hessians in the front facing the main American line. The Americans were deceived when Campbell moved the Light Infantry out of sight of the Americans where they, under the cover of broken terrain, and the New York Volunteers marched to the British rear and circled around to the American right and the road through the swamp.

A British officer, Major Skelly watched the movement from a tall tree to ensure the Americans did not discover the deception. Once beyond the swamp, the British attacked from the flank and the front simultaneously driving the American force from the field. Savannah fell to Campbell and the 71st's 1st Battalion and the New York Volunteers were billeted in the town.

With the capture of Savannah, the British set out in the Southern Campaign to neutralize and isolate the southern States to keep their goods from the more populous North. The British believed that the occupation would entice additional loyalists to join the British.

The 71st Regiment moved inland a few days later along the Savannah River to raise Loyalist support and take the city of Augusta, Georgia. There was virtually no resistance and it is possible that as many as 1,500 Tories were added to British rolls. When Augusta fell, the 71st remained in camp there.

American attention now turned to the worsening situation in the South, and decided to challenge the British in Georgia.

New commander

That winter, Lieutenant Colonel Campbell left for Scotland and Lieutenant Colonel John Maitland assumed command of the 71st Regiment of Foot. He was appointed to command the 1st Battalion on 14 October 1778, though one source gives a promotion date of 9 March 1779.

Briar Creek and Charleston

On 14 February 1779, while the 71st Regiment wintered in Augusta, the Americans defeated a strong Loyalist force in the Battle of Kettle Creek, dispelling belief that the British were in total control of the Colony. American threats to Augusta prompted Campbell's withdrawal of the 71st Regiment from Augusta to Savannah. American troops dogged the retreating British. The king's forces, however, forces engaged those of Generals Ashe and Elbert at the Battle of Briar Creek on 3 March 1779. Lieutenant Colonels Maitland, Prevost, and MacDonald with the 2nd battalion of the 71st as well as the Light Infantry flanked the Americans while Lieutenant Colonel MacPherson's 1st battalion of the 71st diverted attention with a feint. The Americans were routed, with the 71st losing three men and one officer killed, and twelve more men wounded.

After the loss at Briar Creek, a sizeable American force moved upriver towards Augusta in the last days of April 1779. The British in turn threatened undefended Charleston, and in an unnamed skirmish on 24 April 1779, pro-British Creek Indians and the 71st Regiment surprised and swept much of the American forces from their positions, forcing an American retreat into the city. Demands for the city's surrender were met with a plea for neutrality which was rejected. The British lacked the manpower to assault the city and remained inactive.

Stono Ferry

On 20 June 1779, American forces attacked the British rear guard, including the 1st Battalion of the 71st under Lieutenant Colonel Maitland, at Stono Ferry. In all, the force under Maitland included the 1st battalion, a Hessian regiment, and North and South Carolinian provincials, about 500 all told.

On the day of the battle, Maitland’s force was covering a foraging party that had re-crossed the Stono River. Maitland knew that since he was waiting for the foraging party to return, he could not give up his position. Fortunately, Maitland had prepared several redoubts to facilitate defence.

When General Benjamin Lincoln’s forces appeared from the woods, Captain Colin Campbell (Of Glendaruel, Argylshire) and two Highland companies of about 60 men were sent out in skirmish formation to reconnoitre the Americans. The American force far outnumbered Lieutenant Colonel Maitland’s. The American had nearly 3,000 men, including Continentals, North and South Carolina Militia, cavalry, and artillery. Captain Campbell, however, would not withdraw and a determined skirmish ensued. The Highlanders stood their ground and the American advance was temporarily halted. All but seven of the Scotsmen were killed or wounded. When hit, Captain Campbell ordered his men to return to the redoubts, but they refused stating: "that if they left their officers behind in the field, they would bring a lasting disgrace on themselves." When the fighting did slacken, all of the officers were carried back to the redoubt by the seven men who could still walk.

Once the fighting began at Stono Ferry, the 2nd Battalion of the 71st immediately ran for the shore of John’s Island to cross the waterway and into the fight, but the ferries were on the wrong side of the river and the ferrymen fled with the first shots. To remedy the problem, Lieutenant Robert Campbell and several men swam across to retrieve the boats. The 2nd Battalion joined the fight shortly thereafter.

As the 2nd Battalion was crossing, the general engagement began. The Hessians on Maitland’s left were being dislodged by the Carolina Militia which had breached the Hessian redoubt. Maitland shifted two companies of Fraser’s Highlanders from the 1st Battalion to the breach, and the situation stabilized. The arrival of the 2d Battalion tipped the scales to favour the British, and after an hour of heavy fighting, Lincoln’s forces became disorganized and withdrew. The Highlanders pursued the retiring Americans but timely employment of the American cavalry forced the Highlanders to switch over to the defence. In a well synchronized effort, General Lincoln then brought up infantry to rake the Highlanders with musket fire. Maitland began to retire his force. General Lincoln returned to Charleston and the British to Savannah.

In all, the British lost 26 killed and 103 wounded, the Americans 150 killed and wounded. While this small battle had little effect on the overall conduct of the Southern Campaign, it was a severe setback for General Lincoln's force which greatly outnumbered but could not overcome the British.

Savannah

The remainder of the summer of 1779 passed without significant action, the British retaining control of Georgia. In September, arrival of a French fleet with 4,000 soldiers threatened British-held Savannah, with the French desiring to take the port before hurricanes wrecked the fleet. The first attack went in on 16 September 1779, and a surrender demand was made. The British, with 1,100 men in the garrison (including the 1st Battalion of the 71st), were outnumbered.

The British commander used his 24-hour deadline to summon aid from outside the port, including Lieutenant Colonel Maitland’s force of 71st Regiment soldiers (720 all ranks), 200 men of the 2nd Battalion 60th Regiment of Foot, 350 Light Infantry, a small number of Marines, Hessians and Provincial forces from Beaufort, South Carolina. The force arrived at the northern shore of the Savannah River, found it blocked, and was guided by a native fisherman into the city in time to participate in the siege.

Joined by American forces, the French declined to storm the city, and brought up siege guns instead. Men of the garrison did make sorties into Allied lines, including raiding parties from the 71st.

On 8 October 1779, the French launched a direct assault, hoping to expedite the capture of the city and freeing the fleet to make sail before hurricane season. A three-pronged attack was fought back with severe losses on both sides. Both battalions of the 71st took part in repelling the assault, the 2nd from the second line behind the Spring Hill Redoubt, and the 1st Battalion elsewhere in the city where it may have been employed against Brigadier Arthur Dillon or Brigadier General Isaac Huger.

After the direct assault, the siege continued for a few days, before the French fleet sailed away for fear of hurricanes. The Americans were forced to abandon the siege. The 71st remained in Savannah afterwards the siege, where many men fell victim to disease. At one point, over 25% of the regiment was hospitalized, Lieutenant Colonel Maitland died of illness.

Charleston

On 11 February 1780, a large number of reinforcements from England under General Clinton, landed at Edisto Inlet, South Carolina and advanced without opposition. The next day the rest of the embarked troops were landed and the British fleet moved up to blockade Charleston. By 3 March the 2nd Battalion of the 71st Regiment had arrived at James Island where they joined the British Grenadiers. Over the next few days, the 71st moved several times and on 8 March the regiment's light infantry provided cover to the British crossing at Lighthouse Island, becoming the most significant action the regiment would take part in during this siege.

On 28 March 1780, the 1st Battalion arrived in the British camp and the next day joined the main force departing for Charleston, marching in the last of seven divisions. The siege began on 1 April when the British broke ground for their first siege parallel. Kept from escaping from Charleston when he could have by the city’s Assembly, General Lincoln was later asked, by the same politicians, to surrender Charleston without enduring the siege. Charleston was handed over to the British on 12 May, in their third effort to take the city.

Camden

From the siege of Charleston to the end of the war, the 71st Regiment was involved in most of the key battles in the Southern Theatre. In April, General Washington sent needed reinforcements to the Southern District to help save Charleston. Arriving too late to have any impact on the siege, the Continental Congress replaced the Brigadier General Johann de Kalb or, more properly, Johannes von Kalb who was born in the OberBayern town of Kalb near Nurnberg. The OberBayern is equivalent to what we in the US would call the piedmont or foothills approaching the Bavarian Alps, with Major General Horatio Gates as the commander of the forces in the Southern District, who proved a disappointing choice. He chose a route of march hostile to his men, making foraging difficult, and consequently arrived at Camden with an army rife with illness.

On the morning of 16 August 1780, both Cornwallis and his American opponent Gates were moving towards each other for a surprise attack and their armies met at 3:00am. Cornwallis’ force consisted of 2,000 men, including the 71st Regiment (now numbering five companies), the 23rd and 33rd Regiments, the British Legion, Lord Rawdon's Volunteers of Ireland, several Loyalist units, and six guns (four 6-pounders and two 3-pounders). General Gates commanded 3,000 men and several guns.

At daybreak, British and American cavalry clashed on the Charlotte road but neither side gained an advantage; in turn, advancing American infantry was repelled by the British line. Artillery fire announced the start of a general engagement. American militia attempted to advance but hesitated, advancing to within 40 paces of the British only to begin harassing fire on the light infantry. There, the 71st Regiment’s Captain Charles Campbell, watching the activity from a tree stump remarked: "I’ll see you damned first!", and ordered his force forward with the words "Remember you are Light Infantry; Remember you are Highlanders, Charge." The American militia was swept from the field at bayonet point, crumbling the left of the American line. Gates lost his nerve and fled, assuming the battle over. However, the 2nd Maryland Brigade under General De Kalb continued to resist, and Cornwallis ordered up the 71st from reserve with the words "My brave Highlanders, now is your time."

The smoke of the battle prevented the 71st, 23rd, and 33rd from seeing that the American right was intact and General De Kalb rallied several units; the greatly out-numbered Americans fought with determination and held their ground. After De Kalb was fatally wounded and the British cavalry again charged, most of the Americans retreated or surrendered. The British lost 331 of 2,239 men engaged in the battle and Americans losses probably totalled near 700 of the 3,052 engaged.

The battle featured prominently in written literature regarding the 71st, given the critical nature they played in winning the battle.

Fishing Creek

Two days after Camden, the 71st fought again, this time under Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s command against Colonel Thomas Sumter at the Battle of Fishing Creek on 18 August 1780. In this engagement, Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton's 150-man British force found a poorly defended American camp containing Colonel Sumter and about 800 men. In the battle, Captain Campbell of the 71st's light infantry formed his men up with the cavalry for the spontaneous attack. Campbell was killed but nearly the entire American force was killed or captured; with Sumter narrowly escaping by leaping upon his horse and riding, naked or nearly so, to the nearby town of Lancaster, SC.

Kings Mountain

By the end of August 1780, the British had destroyed two American armies in the Southern District, leaving virtually no forces in the South save for partisans. One of these groups shook the entire British plan for the Southern District on 7 October 1780, when the Americans destroyed a large British force in the back woods of South Carolina. The British commander of the partisan force defeated there was Major Patrick Ferguson of the 71st.

In September 1780, Major Ferguson’s Loyalist militia force was sent to cover Cornwallis’ flank as the main British force moved towards Charlotte; tasked to screen and defeat any American militia force that might intervene. In late September, Major Ferguson established himself at Gilbert Town where he sent a message to Patriots in the Appalachians "to desist from their opposition to the British, or that he would march his army over the mountains and hang their leaders." On 24 September, the American militia, or Overmountain Men began to gather at Sycamore Shoals. The two forces pursued each other in the hill country of North and South Carolina; the Americans had hoped to catch Major Ferguson at Gilbert Town and again at Cowpens, but it was a few miles from Cowpens that Major Ferguson’s force took up its last position and battle was joined in the afternoon of 7 October. The Americans advanced under cover of dense woods, to be met with a Loyalist bayonet charge. Major Ferguson manoeuvred his dwindling manpower personally, astride a horse, wearing a chequered hunting shirt and using a great silver whistle to signal his forces. Eventually he was hit by American fire and killed, which brought Loyalist resistance to an end. The Americans killed 225, wounded 163, and took over 700 prisoners while suffering 28 killed and 62 wounded.

Kings Mountain had a major significance to the conduct of the war, forcing Cornwallis to redeploy forces from the coast and towards major cities in the South.

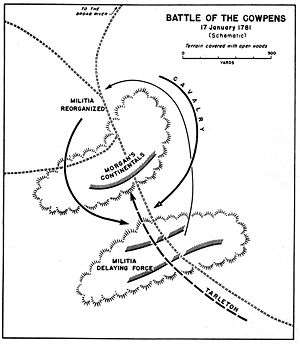

Cowpens

Despite losses at Charleston and Camden, the Americans continued to resist; Washington appointed General Nathaniel Greene to the Southern Army on 3 December 1780. Greene soon moved into South Carolina in a controversial move, splitting the army to ensure enough fodder for both wings and correctly assuming his forces' superior mobility would allow it to fight on ground of its own choosing.

Greene's left wing moved to Cheraw Hill but did not see action, as Cornwallis concentrated against the right wing under General Daniel Morgan. On 27 December 1780, American scouts learned of 250 Tories at Fair Forest, who fled when American cavalry was sent to meet them. Pursuing and routing the Tories, Washington continued on to Fort Williams, whose garrison also retreated. Cornwallis was forced to deal with the thread of the American right wing, and so Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton moved across the Broad River in early January. Joining the 1st battalion of the 71st under his command were 3 pound guns and Tarleton's own Loyalist unit, the British Legion. Tarleton was reinforced by Cornwallis, but terrain made quick movement impossible. A lengthy pursuit of the right wing began, while Cornwallis also sent forces to deal with the left wing.

The American forces converged at Cowpens, received reinforcements, and stopped to make a stand on 17 January 1781. As the forces formed for battle, the 71st we left in reserve. Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton was so focused on attacking quickly that he failed to consider the poor position of his reserves and the terrain’s limits on their manoeuvre. This dramatically affected the battle as the 71st was significantly delayed in joining the fight owing because of the deep underbrush on the British left. Although the main field was clear, the surrounding terrain contained thick underbrush which channelled British movement. Additionally, Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton didn’t allow the 71st time to move into a proper reserve position before the opening of the battle; thereby further worsening their position and ability to react.

After the main engagement got underway, and things went favourably for the British save for actions of the cavalry on the left, Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton, believing victory was at hand, signalled for the reserve. The 71st Regiment and some of his Legion were ordered to strike and envelop the American right. Poor positioning of the regiment prior to the battle came into play dramatically delayed the 71st, and as they struggled forward, the American line of battle fired a deadly volley at 30 to 40 paces with devastating effect on the British line. An American charge resulted in a fierce melee. Major Archibald McArthur, supported by his pipers, rallied the 71st, who stood unflinching in musket fire for 10 to 15 minutes. Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton’s Legion abandoned the regiment’s left flank and most of the Fusiliers threw down their guns and surrendered.

with only the 71st Regiment holding against the encircling Americans, the Georgian Militia charged unsuccessfully against the Regimental Colour. Unsupported and surrounded, the 71st begin to retire, and some even attempted to flee the field. American regulars and militia encircled the regiment by this time, and American Colonel Howard offered Major McArthur quarter, the latter accepting his offer.

The detachment of 71st Regiment men left guarding the baggage train destroyed it and fell back behind the fleeing British cavalry, becoming the only 71st men of the 1st Battalion to escape capture.

As a result of the defeat, the 71st Regiment wore no facings on their uniforms for the rest of the war. Additionally, the surviving officers of the 71st petitioned Lord Cornwallis, asking that the Regiment never serve under Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton again; a request that was approved. At the same time, the 71st was consolidated into a Brigade with the 23rd (Royal Welsh Fusilers) Regiment of Foot and the 33d Regiment of Foot.

Guildford Courthouse

.jpg)

Lord Cornwallis felt that the overall operation in the South could still succeed despite the loss at Cowpens, but to do so, he would have to deal with the growing American forces in the Southern District. Cornwallis set out to chase down the force of American regulars that had defeated Tarleton after the latter's battered forces had consolidated.

By the time Cornwallis began to move into North Carolina and Virginia, General Morgan’s force had already crossed the Broad River. Pursuit of the Americans lasted into February 1781 while the Americans retreated towards their supply lines. Skirmishing began in mid-February, as both armies paused to rest. Not wishing to forestall a decisive battle, Cornwallis managed to engage the Americans in a full-scale battle on 15 March 1781 at Guilford Courthouse.

General Greene sought to emulate the successful deployments of Cowpens, and put his least experienced and reliable North Carolinian militiamen in the centre of the line, at a fence line, opposite the 71st Regiment. The remainder of the line extended to the tree lines and the flanks were guarded by sharpshooters. This formation forced the British into the open along the fence line. The second line, also of militia units, considered more reliable and better trained, was positioned 300 yards (270 m) to the rear. Finally, the Continental regulars were positioned some 500 yards (460 m) further to the American rear.

Cornwallis was outnumbered roughly two-to-one, with only 2,200 troops on the ground and was forced to attack over open ground, beyond which were fences and forests which would make control over the troops difficult, followed by more open ground over which the army would have to pass to engage the Continentals.

The 71st Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Duncan MacPherson began to move at about one in the afternoon as the British line advanced. The British left may have lost as many as a third of its force in engaging the first line of Americans. Captain Dugald Stewart of the 71st said: "One half of the Highlanders dropped on that spot" (Later estimates put the regiment's actual losses that day at about 70 men). After this volley, the British returned fire and drove the American first line from the field with a charge.

The British left then began a contested drive through the second American line and into the open ground in front of the American third. But the British right, including the 71st Regiment, became entangled in a hotly contested skirmish in the woods. This action then split into two, and the 71st were engaged by the Virginia militia in heavy woods, unsupported by any other unit. This was just one of many small battles within the larger battle of Guilford Courthouse where sub-regimental units struggled as individuals and small parties of men without the clearly defined lines which were the convention at the time.

The success of the 71st, along on the British right, now began to support the entire effort. Because the regiment had continued as ordered, they were able to tie-down the Virginia militia in the American second line which prevented them from flanking the British left. Finally, after an exhausting fight, the 71st broke the American second line and the threat to the British flank was eliminated, though the regiment remained in the woods and could provide no support to the main advance on the third American line.

In the end, the day was long and difficult for both sides and neither side could claim a clear victory. The British had swept the field up to the third line, but the Americans succeeded in their goal of inflicting casualties the British could ill-afford. General Greene, believing he had little to gain by remaining, withdrew, leaving the British in possession of the field. The losses at Guilford Courthouse totalled over 500 dead and wounded, of these, the 71st lost Ensign Grant and 11 men killed, with 50 men wounded (including 4 sergeants and 46 other ranks), or a total of 62 casualties.

Yorktown

The battle of Guilford Courthouse concluded, Cornwallis made a strategic decision not to prosecute the war in the Carolinas, but rather to link with American forces in Virginia. The army arrived in Wilmington in early April with fewer than 1,500 men, and continued in late April to Virginia to link up with other forces from New York under Benedict Arnold; by 20 May 1781 Cornwallis commanded 7,500 men.

The two Scottish Regiments under Arnold’s service, the 76th Foot (Macdonald's Highlanders) and the 80th Regiment of Foot (Royal Edinburgh Volunteers) were joined with a Highland force they "revered as the elite of the army, who had fought and generally led in every action during the war". The combined battalions of the 71st by this point numbered only 175 survivors though fairly accurate numbers after the battle of Yorktown put the regiment at over 240 strong.

Cornwallis completed his movement to Hampton Roads in late June and in early July, prepared to evacuate the peninsula at Jamestown and move to Norfolk. The Marquis de Lafayette attacked Lord Cornwallis’ rear at the Battle of Green Spring on 6 July 1781. The 71st did not participate in this engagement. Lord Cornwallis’ forces prevailed and forced a stalemate, moving to Norfolk the next day.

On 26 July 1781, Cornwallis decided to winter at Yorktown, a port town north of Hampton at Gloucester Point on the York River. The movement to Yorktown was complete in late August and work began on fortifications that would encircle the city from the York River in the south up to Yorktown Creek in the north and then back towards the York River. The 71st Regiment of Foot arrived early-on in the landings, but it took 21 days to complete the movement of the British force to Yorktown.

For the first few weeks at Yorktown, work consisted of foraging and construction of fortifications. The former was moderately successful but the latter was too slow to meet the future needs of the British, due mainly to the extreme heat. The British also received help from a number of slaves who had flocked to the British from the local area hoping to win freedom. Additionally, it appears that Cornwallis felt no compulsion to hurry the work since General Lafayette’s forces 25 miles (40 km) away near West Point, Virginia were limited in number and showing no interest in a fight. General Lafayette’s American force did not move closer until 3 September 1871, when it moved into Williamsburg.

At Yorktown, a letter was sent from Lieutenant Colonel Duncan MacPherson, commander of the 71st Regiment. It was written in the first days of September and presumably sent to Lord Cornwallis. The letter painted a picture of the enthusiasm of the regiment. It also refers to "these Highlanders," and thereby possibly the 76th as well as the 71st. The letter begins by announcing that his Regiment heard of the arrival of the French Fleet two days before and then states: "nothing but hard labor goes on here at present in constructing and making Batteries towards the River, and Redoubts towards the Land. The troops are in perfect health and if our Enemies are polite enough to give us three days' grace (we will be ready)."

The letter refers to the arrival of the French Fleet to blockade the Chesapeake. While the British assumed a British fleet from New York would drive off the French, it did not. While he could not know, Lord Cornwallis sea-lanes of communications were permanently cut and the situation at Yorktown would only deteriorate from that point until the surrender.

After the arrival of the French fleet, work on the defences of Yorktown took on new emphasis. When complete, the defences stretched for over a mile around Yorktown. The York River covered the entire rear of the British position, and Gloucester Point, across the York, was defended by a smaller British detachment.

To the north on the right British flank, the defences were anchored by Yorktown Creek, a swampy very rough barrier that ran through a ravine which was all but impassable. Beyond the Creek, the British placed the Fusiliers Redoubt, just astride the York River, to provide cover against any possible Allied approach in that direction. Inside the York Creek, some 600 feet (180 m) towards the town, the main defences ran 1,400 feet (430 m) through the outskirts of the town. This first line moved inland from the river and parallel to the creek. The line there turned left to parallel the river for 2,000 feet (610 m), and terminated in a hornwork that faced the main Allied axis of attack. From the hornwork, the defences turned back to the river, for another 2,000 feet (610 m), ending on the cliffs that protected the port facilities of the town. Two important redoubts protected this last section of line. Redoubts 9 and 10 were located 1,200 ft (370 m) south of the main fortifications. Redoubt 10 was near the cliffs and Redoubt 9 was inland from the river 800 ft (240 m).

These two fortifications played a crucial role in the battle, and Cornwallis knew he must hold them as long as possible. Maybe because of this, both of these key defences were commanded and defended by the 71st Regiment. Major James Campbell and 45 men defended Redoubt 10 and Lieutenant Colonel Duncan MacPherson and 120 men, part of them Hessians, defended Redoubt 9. Lieutenant Colonel MacPherson may have been describing these defences in his intercepted letter to Lord Cornwallis. These defences were well defended and the lynchpin to either side's success.

The Allies prepared their first parallel line beginning on 6 October 1781. The next morning, the parallel stretched across the open fields in front of his line for 2,600 ft (790 m).

Though the circle closed upon Lord Cornwallis, morale was not low. On 11 October, Lord Cornwallis began to consider abandoning Yorktown and escaping across to Gloucester and breaking-out. But the British commander’s attention was soon turned to the opening of the Allies second parallel, only 300 odd yards from the British defences.

On 14 October, the Allies began bombarding Redoubts 9 and 10. That night, the Americans under Alexander Hamilton took Redoubt 10 in a ten-minute bayonet charge. Seventeen men and three officers were taken prisoner. The French under Major General de Vioménil attacked the larger redoubt. This attack lasted 20 minutes before the Redoubt fell to the Allies. Once taken, the two earthworks were incorporated into the Allied line. The circle was fully closed upon the defenders.

On 16 October 1781, the British replied with an attack by 350 men, mostly Grenadiers, Royal Edinburgh Volunteers, and Light Infantry, damaging a handful of Allied guns. Later that day, the Allied second siege line opened fire from their new and deadly positions. That night, Lord Cornwallis decided to retire with his best troops to Gloucester Point and break-out and escape. The forces were divided into divisions and movement began but a storm blew in and ruined Cornwallis’ plan.

At 10:00 am on 17 October 1781, Lord Cornwallis surrendered. On the morning of 18 October 1781, the pipers of the Highland units played a final salute, which was answered by the band of the Franco-German Royal Deux-Ponts Regiment. After the surrender at Yorktown, British forces were marched off to prison camps in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. The men of the 71st Regiment received new kilts while in POW camps, and eventually returned to Perth, Scotland to be discharged in 1783.

The 71st at the End of the War and the Evacuation of Charlestown

On 30 April 1782, the War Office notified Sir Guy Carleton, Commander in Chief of British forces in North America, that due to the death of Lt. General Fraser, the two battalions of the 71st were to be formed into two distinct units, the 71st Regiment under the command of Colonel Thomas Stirling of the 42nd Regiment, and the Second 71st Regiment under the command of the Earl of Balcarres who was appointed a Lt. Colonel Commandant.[1] The latter company was to be augmented by recruits to be raised in the Highlands of Scotland. All private men currently serving in both battalions in America, whether prisoners of war or not, were to be appointed to the new 71st Regiment, as were additional companies at Newfoundland, while additional companies in Britain were to be attached to the Second 71st. The newly organized 71st, consisting of 12 companies, was to continue in service in America, while the commissioned and non-commissioned officers of the Second 71st were to set sail for Britain at the first opportunity.[2]

The two new 71st companies remained in South Carolina until the final evacuation of Charleston on 18 December 1782. The officers of the Second 71st set sail for England in the 203-ton ship Moor, while the remaining men of the 71st Regiment, numbering only 189, were to sail on the 319-ton ship Sally bound for Jamaica.[3] Some of the ships leaving Charleston were bound for St. Augustine, Florida, and it appears likely that at least one member of the 71st was shipwrecked at that port, as archaeologists from the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program have discovered a pewter button from a 71st Regiment uniform on a shipwreck site that appears to date to the 1782 evacuation of Charleston.[4]

References

- ↑ Letter from War Office to Sir Guy Carleton, 30 April 1782, PRO 30/55/39, document 4519, page 1, National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom

- ↑ Letter from War Office to Sir Guy Carleton, 30 April 1782, PRO 30/55/39, document 4519, pages 1-2, National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom

- ↑ List of Transports for the Evacuation of Charleston, 19 November 1782, CO 5/108, folios 37-42, National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom

- ↑ Excavation of the Storm Wreck, Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program

Bibliography

- Baker, Thomas E., Another Such Victory, Eastern Acorn Press, 1981

- Bearss, Edwin, The Battle of Cowpens, Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1967

- Browne, Esq, LLD, A History of the Highlands and of the Highland Clans, A. Fullarton and Co, Edinburgh, 1843

- Campbell, Archibald, Journal of an expedition against the rebels of Georgia in North America under the orders of Archibald Campbell, Esquire, Lieut. Colol. of His Majesty's 71st Regimt., 1778, The Ashantilly Press, Darien, GA, 1981

- Chichester, Henry M, and Burges-Short, George, Records and Badges of Every Regiment in the British Army, London 1900

- Ewald, Johann; Hinrichs, Johann; and Von Juyn, Johann, The Siege of Charleston, New York Times and Arno Press

- Fortescue, John, the Hon, A History of the British Army, Vol III, MacMillan and Co, London, 1911

- Furneaux, Rupert, The Battle of Saratoga, Stein and Day, 1971

- General Return of Officers and Privates Surrendered Prisoners of War, the 19th of October, 1781, to the Allied Army under Command of his Excellency George Washington - taken from the Original Muster-rolls, Archives, State Department Library, Washington, DC

- Graham, James, J. Colonel, Memoir of General Graham: with notices of the campaigns in which he was engaged from 1779 to 1801, R. & R. Clark, Edinburgh, 1862

- Graham, James, The life of General Daniel Morgan of the Virginia Line of the Army of the United States, New York, 1859

- Heinlein, Bruce, Could the British Have Won at Yorktown… with better GEOINT?, GeoInformatics, Brussels, Belgium, 2007

- Katcher, Philip R., Encyclopedia of British, Provincial, and German Army Units 1775-1783, Stackpole Books, 1973

- Keltie, John S., A History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland Clans and Highland Regiments, A Fullerton & Co, Edinburgh 1877, 465

- MacKenzie, Roderick, Strictures On Lt. Col. Tarleton’s History "Of The Campaigns Of 1780 And 1781, In The Southern Provinces Of North America", London, 1787

- MacPherson, Duncan. Letter in George Washington Papers, Library of Congress

- Stewart, David, Major General, Sketches of the Character, Manners, and Present State of the Highlanders of Scotland: With Details of the Military Service of the highland Regiments, Archibald Constable and Co, Edinburgh, 1825

- Thompson, Erwin N., Historic Resource Study, The British Defenses of Yorktown, 1781, US Park Service, 1976

US Geological Survey Chart, 1:24,000, Colonial National Historical Park, 37076-B5-PF-025, 1981

- Wood, William J. Battles of the Revolutionary War, Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, NC, 1990