Acherontia atropos

| African death's head hawkmoth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Acherontia atropos ♀ MHNT | |

| |

| Acherontia atropos ♀ △ MHNT | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Sphingidae |

| Genus: | Acherontia |

| Species: | A. atropos |

| Binomial name | |

| Acherontia atropos (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| |

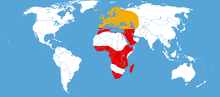

| Distribution map (red: all year distribution; orange: summer distribution possible) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Acherontia atropos (Greater death's head hawkmoth) is the most widely known of the three species of death's-head hawkmoth. Acherontia species are notorious for a vaguely skull-shaped pattern on the thorax.

Appearance

Acherontia atropos is a large hawk moth with a wingspan of 90–130 mm (about 3.5 to 5 inches), being the largest moth in some of the regions in which it occurs. The adult has the typical streamlined wings and body of the hawk moth family, Sphingidae. The upper wings are brown with slight yellow wavy lines; the lower wings are yellow with some wide brown waves. It rests during the day on trees or in the litter, holding the wings like a tent over the body.

The moth also has numerous other unusual features. It has the ability to emit a loud squeak if irritated. The sound is produced by expelling air from its proboscis. It often accompanies this sound with flashing its brightly marked abdomen in a further attempt to deter its predators. It is commonly observed raiding beehives for honey at night. Unlike the other species of Acherontia, it only attacks colonies of the well-known Western honey bee, Apis mellifera. It is attacked by guard bees at the entrance, but the thick cuticle and resistance to venom allow it to enter the hive. It is able to move about in hives unmolested because it mimics the scent of the bees.[1]

The British entomological journal Atropos takes its name from this species.

Etymology

The species name Atropos is related to death, derived from atropos that may not be turned, from a-1 + -tropos (Greek: τρόπος) from trepein to turn. Atropos was one of the three Moirai, goddesses of fate and destiny. In addition the genus name Acherontia is derived from Acheron, a river in Greece, which in Greek mythology was known as the river of pain, and was one of the five rivers of the Greek underworld.

Distribution

Acherontia atropos occurs throughout the Middle East and the Mediterranean region, much of Africa down to the southern tip, and increasingly as far north as southern Great Britain due to recently mild British winters. It occurs as far east as India and western Saudi Arabia, and as far west as the Canary Islands and Azores. It invades western Eurasia frequently, although few individuals successfully overwinter.[2]

Development

There are several generations of Acherontia atropos per year, with continuous broods in Africa. In the northern parts of its range the species overwinters in the pupal stage. Eggs are laid singly under old leaves of Solanaceae: potato especially, but also Physalis and other nightshades. However it also has been recorded on members of the Verbenaceae, e.g. Lantana, and on members of the families Cannabaceae, Oleaceae,[3] Pedaliaceae and others. The larvae are stout with a posterior horn, as is typical of larvae of the Sphingidae. Most sphingid larvae however, have fairly smooth posterior horns, possibly with a simple curve, either upward or downward. In contrast, Acherontia species and certain relatives bear a posterior horn embossed with round projections about the thicker part. The horn itself bends downwards near the base, but curls upwards towards the tip.

The newly hatched larva starts out a light shade of green but darkens after feeding, with yellow stripes diagonally on the sides. In the second instar, it has thorn-like horns on the back. In the third instar, purple or blue edging develops on the yellow stripes and the tail horn turns from black to yellow. In the final instar, the thorns disappear and the larva may adopt one of three color morphs: green, brown, or yellow. Larvae do not move much, and will click their mandibles or even bite if threatened, though the bite is effectively harmless to the human skin. The larva grows to about 120–130 mm, and pupates in an underground chamber. The pupa is smooth and glossy with the proboscis fused to the body, as in most Lepidoptera.[2]

Folklore

In spite of the fact that Acherontia atropos is perfectly harmless except as a minor pest to crops and to beehives,[4] the fancied skull pattern has burdened the moth with a negative reputation, such as associations with the supernatural and evil. There are numerous superstitions to the effect that the moth brings bad luck to the house into which it flies, and that death or grave misfortune may be expected to follow. More prosaically, in South Africa at least, uninformed people have claimed that the moth has a poisonous, often fatal, sting (possibly referring mainly to the proboscis, but sometimes to the horn on the posterior of the larva).[5]

Acherontia atropos has been featured in various visual arts. It was painted by Vincent van Gogh in his Death's-head Hawkmoth on Arum (Grote nachtpauwoog), 1889.[6] It appeared in The Hireling Shepherd, in Bram Stoker's "Dracula" and in movies such as Un chien andalou and the promotional marquee posters for The Silence of the Lambs. In the latter film the moth is used as a calling card by the serial killer "Buffalo Bill", though the movie script refers to Acherontia styx, and the moths that appear in the film are Acherontia atropos. In The Mothman Prophecies this moth is referred to. It also appears in the music video to Massive Attack's single, "Butterfly Caught."

The Death's-head moth is mentioned in Susan Hill's gothic horror novel, I'm the King of the Castle as it is used to instil fear in one of the young protagonists.

John Keats mentioned the moth as a symbol of death in his Ode to Melancholy, "Make not your rosary of yew-berries, / Nor let the beetle, nor the death-moth be / Your mournful Psyche".[7]

In José Saramago's novel Death With Interruptions, Acherontia atropos appears on the American edition's cover, and is a topic that two characters mull over.

References

- ↑ Moritz, RFA, WH Kirchner and RM Crewe. 1991. Chemical camouflage of the death's head hawkmoth (Acherontia atropos L.) in honeybee colonies. Naturwissenschaften 78 (4): 179-182.

- 1 2 Pittaway, AR. 1993. The hawkmoths of the western Palaearctic. Harley Books, London.

- ↑ Alan Weaving; Mike Picker; Griffiths, Charles Llewellyn (2003). Field Guide to Insects of South Africa. New Holland Publishers, Ltd. ISBN 1-86872-713-0.

- ↑ Smit, Bernard, "Insects in South Africa: How to Control them", Pub: Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1964.

- ↑ Skaife, Sydney Harold (1979). African insect life, second edition revised by John Ledger and Anthony Bannister. Cape Town: C. Struik. ISBN 0-86977-087-X.

- ↑ Van Gogh, Vincent (June 1889). "Grote nachtpauwoog". Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Full Text of John Keat's "Ode to Melancholy"". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acherontia atropos. |

- A. atropos detailed information

- Description in Richard South The Moths of the British Isles

- Sound recording of Acherontia atropos at BioAcoustica