Action of 4 April 1808

| Action of 4 April 1808 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

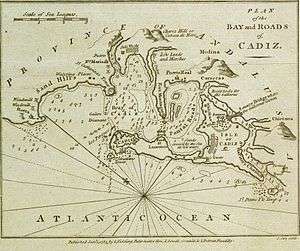

Battle location in Cadiz Bay. Rota is on left of map | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Captain Murray Maxwell | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Frigates: HMS Mercury HMS Alceste HMS Grasshopper |

large number of merchantmen, 20 gunboats, shore batteries[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 killed, 2 wounded 1 Frigate damaged[2] |

Unknown casualties, 7 merchants captured, 2 gunboats destroyed, 7 gunboats run ashore[3][4] | ||||||

The Action of 4 April 1808 was a naval engagement off the coast off Rota near Cadiz, Spain where Royal Naval frigates Mercury, Alceste and Grasshopper intercepted a large Spanish convoy protected by twenty gunboats and a train of batteries close to shore.

Background

Blockade duties around Cadiz were still being carried out by the Royal Navy over two years since Trafalgar (1805). The intention was the same as it was in 1805 to keep the Franco-Spanish fleet 'locked up' and also to keep a watchful eye on any movements by sea and attack if necessary. These included vessels such as that under the command of Captain Murray Maxwell with his 38-gun frigate Alceste, 28-gun frigate Mercury, Captain James Alexander Gordon, and 18-gun brig-sloop Grasshopper (16 carronades, 32-pounders, and two long sixes), under Captain Thomas Searle

Attack

38-gun frigate Alceste Captain Murray Maxwell, 28-gun frigate Mercury, Captain James Alexander Gordon, and 18-gun brig-sloop Grasshopper (16 carronades, 32-pounders, and two long sixes), Captain Thomas Searle, lay at anchor about three miles to the north-west of the lighthouse of San-Sebastian, near Cadiz, a large convoy, under the protection of about 20 gun-boats and a numerous train of flying' artillery on the beach, was observed coming down close along-shore from the northward. At 3 p.m., the Spanish convoy being then abreast of the town of Rota, the Alceste and squadron weighed, with the wind at west-south-west, and stood in for the body of the Spanish vessels.[5]

At 4 p.m. the shot and shells from the Spanish gun-boats and batteries passing over them, the British ships opened their fire. The Alceste and Mercury devoted their principal attention to the gun boats; while the Grasshopper, drawing much less water, stationed herself upon the shoal to the southward of the town and so close to the batteries, that by the grape from her carronade drove the Spaniards from their guns, and at the same time kept in check a division of gun-boats, which had come out from Cadiz to assist those engaged by the two frigates. The situation of the Alceste and Mercury was also rather critical, they having in the state of the wind, to tack every fifteen minutes close to the end of the shoal.[6]

The first Lieutenant of the Alceste Lieutenant Stewart intended to board the convoy with boats. Accordingly, the boats of the Alceste with marines set off and the boats of the Mercury quickly followed. As they came across the convoy, the two divisions of boats, led by Lieutenant Stewart, soon boarded and brought out seven merchants, from under the very muzzles of the Spanish guns and from under the protection of the barges and pinnaces of the Franco-Spanish squadron of seven sail of the line; which barges and pinnaces had also by that time effected their junction with the gun-boats. By early evening the action had ended and the 3 frigates set off with the captured prizes.[7]

Aftermath

Exclusive of the seven merchants captured, two of the gun-boats were destroyed, and another seven had run on shore by the fire from the two British frigates and brig. The merchants contained ship timber, gunpowder and weapons. The cost to the British was one dead and two slightly wounded on board the Grasshopper. The damages of the latter, however, were extremely severe, as well in hull, masts, rigging and sails. With the exception of an anchor shot away from the Mercury, the damages of the two frigates were confined to their sails and ridging.[8]

Notes

References

- Perrett Bryan, The Real Hornblower: The Life and Times of Admiral Sir James Gordon, GCB (London, 1998) ISBN 1-55750-697-3

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8. OCLC 67375475.

- Winfield, Rif, British Warships of the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates Seaforth 2007; ISBN 1-86176-295-X