Alexandru Ioan Cuza

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Styles of Alexandru Ioan Cuza | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Royal Highness |

| Spoken style | Your Royal Highness |

| Alternative style | Sir |

Alexandru Ioan Cuza (pronounced [alekˈsandru iˈo̯an ˈkuza], or Alexandru Ioan I, also anglicised as Alexander John Cuza; 20 March 1820 – 15 May 1873) was Prince of Moldavia, Prince of Wallachia, and later Domnitor (ruler) of the Romanian Principalities. He was a prominent figure of the Revolution of 1848 in Moldavia. He initiated a series of reforms that contributed to the modernization of Romanian society and of state structures.

Early life

Born in Bârlad, Cuza belonged to the traditional boyar class in Moldavia, being the son of Ispravnic Ioan Cuza (who was also a landowner in Fălciu County) and his wife Sultana (or Soltana), a member of the Cozadini family of Phanariote origins. Alexander received an urbane European education, becoming an officer in the Moldavian Army (rising to the rank of colonel). He married Elena Rosetti in 1844. In 1848, known as the year of European revolutions, Moldavia and Wallachia fell into revolt. The Moldavian unrest was quickly suppressed, but in Wallachia the revolutionaries took power and governed during the summer (see 1848 Wallachian revolution). Young Cuza played a prominent enough part so as to establish his liberal credentials during the Moldavian episode and to be shipped to Vienna as a prisoner, where he made his escape with British support.

Returned during the reign of Prince Grigore Alexandru Ghica, he became Moldavia's minister of war in 1858 representing also Galați in the ad hoc Divan at Iași. Cuza was acting freely under the guarantees of the European Powers in the eve of the Crimean War for a recognition of the Prince of Moldavia. Cuza was a prominent speaker in the debates and strongly advocated the union of Moldavia and Walachia. In default of a foreign prince, he was nominated as a candidate in both principalities by the pro-unionist Partida Națională (profiting of an ambiguity in the text of the Treaty of Paris). Cuza was finally elected as Prince of Moldavia on 17 January 1859 (5 January Julian) and, after "street pressure" changed the vote in Bucharest, also Prince of Wallachia, on 5 February 1859 (24 January Julian). He received the firman from the Sultan on 2 December 1861 during a visit to Istanbul. He was recipient of the Order of Medjidie, Order of Osmanieh, Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus and Order of the Redeemer.

Although he and his wife Elena Rosetti had no children, she raised as her own children his two sons from his mistress Elena Maria Catargiu-Obrenović: Alexandru Al. Ioan Cuza (1864–1889), and Dimitrie Cuza (1865–1888 suicide).

Reign

Diplomatic efforts

Thus Cuza achieved a de facto union of the two principalities. The Powers backtracked, Napoleon III of France remaining supportive, while the Austrian ministry withheld approval of such a union at the Congress of Paris (18 October 1858); partly as a consequence, Cuza's authority was not recognized by his nominal suzerain, Abdülaziz, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, until 23 December 1861, (and, even then, the union was only accepted for the duration of Cuza's rule).

The union was formally declared three years later, on 5 February 1862, (24 January Julian), the new country bearing the name of Romania, with Bucharest as its capital city.

Cuza invested his diplomatic actions in gaining further concessions from the Powers: the sultan's assent to a single unified parliament and cabinet for Cuza's lifetime, in recognition of the complexity of the task. Thus, he was regarded as the political embodiment of a unified Romania.

Reforms

Assisted by his councilor Mihail Kogălniceanu, an intellectual leader of the 1848 revolution, Cuza initiated a series of reforms that contributed to the modernization of Romanian society and of state structures.

His first measure addressed a need for increasing the land resources and revenues available to the state, by "secularizing" (confiscating) monastic assets in 1863.[2] Probably more than a quarter of Romania's farmland was controlled by untaxed Eastern Orthodox "Dedicated Monasteries", which supported Greek and other foreign monks in shrines such as Mount Athos and Jerusalem (a substantial drain on state revenues). Cuza got his parliament's backing to expropriate these lands. He offered compensation to the Greek Orthodox Church, but Sophronius III, the Patriarch of Constantinople, refused to negotiate; after several years, the Romanian government withdrew its offer and no compensation was ever paid. State revenues thereby increased without adding any domestic tax burden. The land reform, liberating peasants from the last corvées, freeing their movements and redistributing some land (1864), was less successful.[2] In attempting to create a solid support base among the peasants, Cuza soon found himself in conflict with the group of Conservatives. A liberal bill granting peasants title to the land they worked was defeated. Then the Conservatives responded with a bill that ended all peasant dues and responsibilities, but gave landlords title to all the land. Cuza vetoed it, then held a plebiscite to alter the Paris Convention (the virtual constitution), in the manner of Napoleon III.

His plan to establish universal manhood suffrage, together with the power of the Domnitor to rule by decree, passed by a vote of 682,621 to 1,307. He consequently governed the country under the provisions of Statutul dezvoltător al Convenției de la Paris ("Statute expanding the Paris Convention"), an organic law adopted on 15 July 1864. With his new plenary powers, Cuza then promulgated the Agrarian Law of 1863. Peasants received title to the land they worked, while landlords retained ownership of one third. Where there was not enough land available to create workable farms under this formula, state lands (from the confiscated monasteries) would be used to give the landowners compensation.

Despite the attempts by Lascăr Catargiu's cabinet to force a transition in which some corvées were to be maintained, Cuza's reform marked the disappearance of the boyar class as a privileged group, and led to a channeling of energies into capitalism and industrialization; at the same time, however, land distributed was still below necessities, and the problem became stringent over the following decades – as peasants reduced to destitution sold off their land or found that it was insufficient for the needs of their growing families.

Cuza's reforms also included the adoption of the Criminal Code and the Civil Code based on the Napoleonic code (1864), a Law on Education, establishing tuition-free, compulsory public education for primary schools[2] (1864; the system, nonetheless, suffered from drastic shortages in allocated funds; illiteracy was eradicated about 100 years later, during the communist regime). He founded the University of Iași (1860) and the University of Bucharest (1864), and helped develop a modern, European-style Romanian Army, under a working relationship with France. He is the founder of the Romanian Naval Forces.

Downfall and exile

Cuza failed in his effort to create an alliance of prosperous peasants and a strong liberal prince, ruling as a benevolent authoritarian in the style of Napoleon III. Having to rely on a decreasing group of hand-picked bureaucrats, Cuza began facing a mounting opposition after his land reform bill, with liberal landowners voicing concerns over his ability to represent their interests. Along with financial distress, there was an awkward scandal that revolved around his mistress, Maria Catargiu-Obrenović, and popular discontent culminated in a coup d'état.

Cuza was forced to abdicate by the so-called "monstrous coalition" of Conservatives and Liberals. At four o'clock on the morning of 22 February 1866, a group of military conspirators broke into the palace, and compelled the prince to sign his abdication. On the following day they conducted him safely across the frontier.

His successor, Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, was proclaimed Domnitor as Carol I of Romania on 20 April 1866. The election of a foreign prince with ties to an important princely house, legitimizing Romanian independence (which Carol came to do after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878), had been one of the liberal aims in the revolution of 1848.

Despite the participation of Ion Brătianu and other future leaders of the Liberal Party in the overthrow of Cuza, he remained a hero to the radical and republican wing, who, as Francophiles, had an additional reason to oppose a Prussian monarch; anti-Carol riots in Bucharest during the Franco-Prussian War (see History of Bucharest) and the coup attempt known as the Republic of Ploiești in August 1870, the conflict was eventually resolved by the compromise between Brătianu and Carol, with the arrival of a prolonged and influential Liberal cabinet.

Cuza spent the remainder of his life in exile, chiefly in Paris, Vienna and Wiesbaden, accompanied by his wife, his mistress, and his two sons. He died in Heidelberg. His remains were buried in his residence in Ruginoasa, but were moved to the Trei Ierarhi Cathedral in Iași after World War II.

Notes

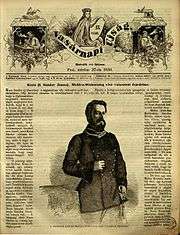

- ↑ (Romanian) "Vasárnapi Ujság este unul din numeroasele publicații care apăreau atunci și care au relatat și comentat cu simpatie și respect alegerea lui Cuza" http://actualitateasm.ro/stiri/22661-publicatia-vasarnapi-ujsag-saluta-la-1859-dubla-alegere-a-lui-alexandru-ioan-cuza/

- 1 2 3 Stoica, Vasile (1919). The Roumanian Question: The Roumanians and their Lands. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Company. pp. 69–70.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Alexandru Ioan Cuza |

- Cuza, Alexandru Ioan (1820-1870), by Gerald J. Bobango and Paul E. Michelson, at the Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions.

| Alexandru Ioan Cuza House of Cuza Born: 20 March 1820 Died: 15 May 1873 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Title created |

Domnitor of Romania 5 February 1862 – 22 February 1866 |

Succeeded by Carol I |

| Preceded by Grigore Alexandru Ghica |

Prince of Moldavia 24 January 1859 – 5 February 1862 |

Succeeded by Title abandoned |

| Preceded by Barbu Știrbei |

Prince of Wallachia 24 January 1859 – 5 February 1862 |

Succeeded by Title abandoned |