Andrew Prine

| Andrew Prine | |

|---|---|

|

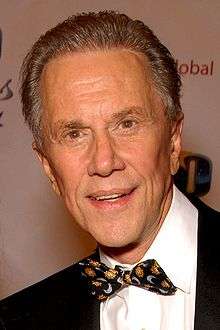

Andrew Prine attending the "Night of 100 Stars" for the 82nd Academy Awards viewing party at the Beverly Hills Hotel in Beverly Hills, California, on March 7, 2010 | |

| Born |

Andrew Lewis Prine February 14, 1936 Jennings, Florida, U.S. |

| Years active | 1957–present |

| Spouse(s) |

Sharon Farrell (1962–1962; divorced) Brenda Scott (1965–1966; 1968–1969; 1973-1978 divorced) Heather Lowe (1986–present) |

Andrew Lewis Prine (born February 14, 1936) is an American film, stage, and television actor.

Early life and career

Prine was born in Jennings in Hamilton County in northern Florida. After graduation from Miami Jackson High School in Miami, Prine made his acting debut three years later in an episode of CBS's United States Steel Hour. His next role was in the 1959 Broadway production of Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward, Angel.[1] In 1962, Prine was cast in Academy Award-nominated film, The Miracle Worker as Helen Keller's older brother, James.

In 1962, Prine landed a lead role with Earl Holliman in the 28-episode NBC series, The Wide Country, a drama about two brothers who are rodeo performers.

After The Wide Country, Prine continued to work throughout the 1960s and 1970s, appearing in films with John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, William Holden, and Dean Martin and on television series such as Gunsmoke, Bonanza, The Virginian, Wagon Train, Dr. Kildare, Baretta, Hawaii Five-O, Twelve O'Clock High, and The Bionic Woman. He played Dr. Richard Kimble's brother Ray in an important first-season episode of The Fugitive. During the 1980s and 1990s, Prine continued to work in film and television. In the 1983–84 season, he appeared on W.E.B., Dallas, Weird Science, Boone, and as Steven in the science fiction miniseries V and its sequel V: The Final Battle.

Most recently, Prine has worked with director Quentin Tarantino on an Emmy-winning episode of CSI and in Saving Grace with Holly Hunter, Boston Legal and Six Feet Under in addition to feature films with Johnny Knoxville. The Encore Western Channel has featured him on Conversations with Andrew Prine interviewing Hollywood actors like Eli Wallach, Harry Carey, Jr., Patrick Wayne, and film makers such as Mark Rydell with behind-the-scenes anecdotes.

A life member of The Actors Studio,[2] Prine's stage work includes Long Day's Journey into Night with Charlton Heston and Deborah Kerr, The Caine Mutiny, directed by Henry Fonda, and A Distant Bell on Broadway. He has received the Golden Boot Award for his body of work in Westerns and two Best Actor Dramalogue awards.

Personal life

In 1962, Prine married actress Sharon Farrell, but the marriage ended a few months later.

Prine married actress Brenda Scott in 1965; the marriage ended after one month. While Prine and Scott remarried in 1966, their second marriage also ended in divorce. Following their second divorce, Prine and Scott co-starred as brother and sister in the NBC western series The Road West from 1966–1967. In 1973, Prine and Scott tried marriage yet again. Their third marriage also ended in divorce; this time after five years, in 1978.

Prine married his third wife, actress Heather Lowe, in 1986.

Murder suspect

In 1962, Prine met a 21-year-old actress, Karyn Kupcinet, when she guest-starred on one episode of The Wide Country.[3] They began a relationship. When Kupcinet was found dead three days after she was murdered in the early morning hours of Thanksgiving Day, November 28, 1963, the subsequent investigation led the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department to consider Prine as one of their chief suspects.[3] Newspapers did not report his status as a suspect or that anyone else was a suspect.[3] The coroner determined Kupcinet had been strangled; her nude body was found in her Los Angeles apartment by friends, the married couple Mark Goddard and Marcia Rogers Goddard.[3]

When questioned by law enforcement, Andrew Prine said he had talked with Kupcinet twice by phone on Wednesday, the day before her murder, in an attempt to patch up an argument they had had.[3] Two other men were also named as suspects; both were friends of Prine. Each stated that together they had visited Kupcinet on Wednesday evening and watched television with her, including The Danny Kaye Show, and they left when she went to bed for the night. Prine was not with them at Kupcinet's home; they saw him elsewhere later that night.[3]

According to reports from sheriff's investigators, Prine and Kupcinet had been receiving hand-made, anonymous death threats for several weeks prior to the murder, and these messages had been created from letters and words cut out of magazine headlines. The Chicago Tribune and other newspapers reported on December 5 and 6, 1963 that detectives had found Kupcinet's fingerprints on a piece of Scotch Tape used to create one of the messages, leading them to believe Kupcinet had been the person making the threats. (Whoever sent them hand-delivered them to Prine's home and Kupcinet's home instead of mailing them with postage stamps.) Prine told investigators that when he and Kupcinet had met to show each other the threatening messages, she had acted puzzled and clueless about who could have done such a thing.[3]

After reports that investigators had matched fingerprints from the Scotch tape to ones from Kupcinet's 1962 arrest for shoplifting, all newspapers dropped the story. In the December 1998 issue of GQ magazine, however, crime writer James Ellroy claimed that Andrew Prine and his two friends had been questioned by the sheriff's department many times throughout the 1960s until as late as 1969.

In 1988, Karyn Kupcinet's father, syndicated newspaper columnist Irving Kupcinet, published a memoir in which he revealed that he and his wife Essee, Karyn's mother, believed that Andrew Prine had nothing to do with her murder.[4] They believed the culprit was a neighbor in her apartment complex in West Hollywood, California who had no connection to Prine or either of the friends who visited her a few hours before the murder.[4] Irving Kupcinet stated further that he and his wife believed that the culprit's wealthy family had hired lawyers who blocked sheriff's investigators from questioning him.[5]

According to the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department, Karyn Kupcinet's murder was never solved and remains a cold case.[6][7]

Filmography

- Kiss Her Goodbye (1959)

- The Miracle Worker (1962)

- Advance to the Rear (1964)

- Texas Across the River (1966)

- The Devil's Brigade (1968)

- Bandolero! (1968)

- Lost Flight (1969)

- This Savage Land (1969)

- Generation aka A Time for Caring, A Time for Giving (1969)

- Along Came a Spider (1970)

- Chisum (1970)

- Night Slaves (1970)

- Simon, King of the Witches (1971)

- Another Part of the Forest (1972)

- Squares aka Honky Tonk Cowboy, Riding Tall (1972)

- One Little Indian (1973)

- Crypt of the Living Dead aka La tumba de la isla maldita, Vampire Women (1973)

- Wonder Woman (1974)

- Centerfold Girls (1974)

- Nightmare Circus (1974)

- Rooster Cogburn (Uncredited, 1975)

- The Town That Dreaded Sundown (1976)

- The Deputies aka The Law of the Land (1976)

- Grizzly (1976)

- The Winds of Autumn (1976)

- The Evil (1978)

- Amityville II: The Possession (1982)

- They're Playing with Fire (1984)

- Eliminators (1986)

- Chill Factor (1990)

- Life on the Edge (1992)

- Deadly Exposure (1992)

- Gettysburg (1993)

- Without Evidence (1995)

- The Dark Dancer (1995)

- Serial Killer (1995)

- The Shadow Men (1998)

- Possums (1998)

- The Boy with the X-Ray Eyes aka X-Ray Boy, X-treme Teens (1999)

- Critical Mass (2000)

- Witchouse 2: Blood Coven (2000)

- Sweet Home Alabama (Uncredited, 2002)

- Gods and Generals (Uncredited, 2003)

- The Dukes of Hazzard (2005)

- Glass Trap (2005)

- Hell to Pay (2005)

- Daltry Calhoun (2005)

- Lords of Salem (2012)

Television

- U.S. Steel Hour (1 episode, 1957)

- Playhouse 90 (1 episode, 1960)

- Alcoa Presents: One Step Beyond (1 episode, 1960)

- Overland Trail (1 episode, "Sour Annie", 1960)

- Peter Gunn (1 episode, 1960)

- The DuPont Show of the Month (1 episode, 1961)

- Have Gun — Will Travel (2 episodes, 1960–1961)

- Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1 episode, 1962)

- The Defenders (1 episode, 1962)

- Alcoa Premiere (2 episodes, 1961–1962)

- The New Breed (1 episode, 1962)

- Ben Casey (1 episode, 1962)

- The Wide Country (28 episodes, 1962–1963)

- Vacation Playhouse (1 episode, 1963)

- Gunsmoke (3 episodes, 1962–1963)

- The Lieutenant (1 episode, 1963)

- The Great Adventure (1 episode, 1963)

- Advance to the Rear (1964)

- Profiles in Courage (1 episode, 1964)

- Wagon Train aka Major Adams, Trail Master (2 episodes, 1964–1965)

- Combat! (1 episode, 1965)

- Kraft Suspense Theatre (1 episode, 1965)

- Bonanza (1 episode, 1965)

- Dr. Kildare (7 episodes, 1963–1965)

- Convoy (1 episode, 1965)

- Twelve O'Clock High (2 episodes, 1964–1965)

- The Fugitive (2 episodes, 1964–1965)

- The Road West (Unknown episodes, 1966)

- Tarzan (1 episode, 1966)

- The Invaders (1 episode, 1967)

- Daniel Boone (1 episode, 1968)

- Felony Squad (1 episode, 1968)

- Ironside (2 episodes, 1968)

- The Virginian (5 episodes, 1965–1969)

- Love, American Style (1 episode, 1969)

- Insight (1 episode, 1970)

- Lancer (2 episodes, 1968–1970)

- The Name of the Game (2 episodes, 1968–1970)

- Matt Lincoln (1 episode, 1970)

- The Most Deadly Game (1 episode, 1970)

- Dan August (1 episode, 1970)

- The Courtship of Eddie's Father (1 episode, 1971)

- Dr. Simon Locke aka Police Surgeon (1 episode, 1971)

- The F.B.I. (3 episodes, 1968–1973)

- The Delphi Bureau (1 episode, 1973)

- Kung Fu (1 episode, 1974)

- Banacek (1 episode, 1974)

- Hawkins (1 episode, 1974)

- Barnaby Jones (2 episodes, 1973–1974)

- Cannon (2 episodes, 1971–1974)

- Amy Prentiss (1 episode, 1974)

- Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1 episode, 1975)

- Barbary Coast (1 episode, 1975)

- Hawaii Five-O (1 episode, 1975)

- The Family Holvak (2 episodes, 1975)

- Riding With Death (1 episode, 1976)

- Baretta (2 episodes, 1975–1976)

- Quincy, M.E. (1 episode, 1977)

- Tail Gunner Joe (1977)

- Hunter (1 episode, 1977)

- The Bionic Woman (1 episode, 1977)

- The Last of the Mohicans (1977)

- Christmas Miracle in Caufield, U.S.A. aka The Christmas Coal Mine Miracle (1977)

- Abe Lincoln: Freedom Fighter (1978)

- W.E.B. (5 episodes, 1978)

- Donner Pass: The Road to Survival (1978)

- Flying High (1 episode, 1979)

- Mind Over Murder (1979)

- The Littlest Hobo (2 episodes, 1979)

- M Station: Hawaii (1980)

- One Day at a Time (1980)

- Callie & Son aka Callie and Son aka Rags to Riches (1981)

- A Small Killing (1981)

- Darkroom (1 episode, Undated)

- Hart to Hart (1 episode, 1982)

- The Fall Guy (1 episode, 1983)

- V aka V: The Original Miniseries (1983)

- Boone as A.W. Holly in "The Graduation" (1983)

- Trapper John, M.D. (1 episode, 1984)

- No Earthly Reason (1984)

- They're Playing with Fire (1984)

- V: The Final Battle (1984)

- Matt Houston (2 episodes, 1984)

- Cover Up (1 episode, 1984)

- And the Children Shall Lead aka Wonderworks: And the Children Shall Lead (1985)

- Danger Bay (2 episodes, 1986)

- Paradise aka Guns of Paradise (1 episode, 1988)

- Dallas (1 episode, 1989)

- Freddy's Nightmares aka Freddy's Nightmares: A Nightmare on Elm Street: The Series (2 episode, 1989)

- In the Heat of the Night (1 episode, 1990)

- Murder, She Wrote (4 episodes, 1984–1991)

- Parker Lewis Can't Lose (1 episode, 1991)

- Mission of the Shark: The Saga of the U.S.S. Indianapolis (1991)

- Matlock (1 episode, 1991)

- FBI: The Untold Stories (1 episode, 1992)

- Room for Two (26 episodes, 1992)

- Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman (1 episode, 1993)

- Star Trek: The Next Generation (1 episode, 1993)

- Scattered Dreams aka Scattered Dreams: The Kathryn Messenger Story (1993)

- Married... with Children (1 episode, 1994)

- Weird Science (Unknown episodes, 1994–1996)

- Night Stand with Dick Dietrick (1 episode, 1995)

- The Avenging Angel (1995)

- Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1 episode, 1995)

- University Hospital (1 episode, 1995)

- Pointman (1 episode, 1995)

- Baywatch Nights (1 episode, 1996)

- Melrose Place (1 episode, 1996)

- Walker, Texas Ranger aka Walker (1 episode, 1997)

- Silk Stalkings (1 episode, 1997)

- JAG (1 episode, 1999)

- The Miracle Worker (2000)

- James Dean (2001)

- Six Feet Under (2 episodes, 2004)

- CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (2005)

- Boston Legal (1 episode, 2006)

- Hollis & Rae (2006)

- Saving Grace (1 episode, 2008)

References

- ↑ Parkway Playhouse Archived June 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Garfield, David (1980). "Appendix: Life Members of The Actors Studio as of January 1980". A Player's Place: The Story of The Actors Studio. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc. p. 279. ISBN 0-02-542650-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ellroy, James (1999). Crime Wave: Reportage and Fiction From the Underside of L.A. Random House, Inc. ISBN 0-375-70471-X.

- 1 2 Kupcinet, Irving (1988). Kup: A Man, An Era, A City. Bonus Books. pp. 186–188. ISBN 0-933893-70-1.

- ↑ Kupcinet, Irving (1988). Kup: A Man, An Era, A City. Bonus Books. p. 187. ISBN 0-933893-70-1.

- ↑ By Stephan Benzkofer (November 24, 2013). "Karyn Kupcinet 1963 death still unsolved". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ Phil Potempa (November 29, 2013). "OFFBEAT: Chicago gossip columnist Kup never forgot beloved daughter". Northwest Indiana Times. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

External links

- Andrew Prine at the Internet Movie Database

- AndrewPrineArt.com - original paintings