James Tod

| Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod | |

|---|---|

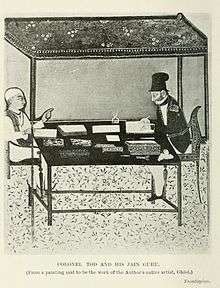

The frontispiece of the 1920 edition of Tod's Annals and Antiquities of Rajas'han | |

| Born |

20 March 1782 Islington, London, UK |

| Died |

18 November 1835 (aged 53) London |

| Cause of death | Apoplectic fit |

| Occupation | Political Agent; historian; cartographer; numismatist |

| Employer | East India Company |

| Notable work | Annals and Antiquities of Rajas'han; Travels in Western India |

| Spouse(s) | Julia Clutterbuck (m. 1826–35) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

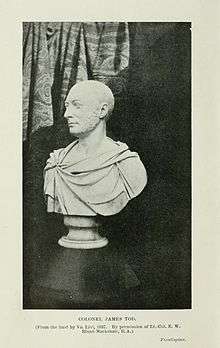

Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod (20 March 1782 – 18 November 1835) was an English-born officer of the British East India Company and an Oriental scholar. He combined his official role and his amateur interests to create a series of works about the history and geography of India, and in particular the area then known as Rajputana that corresponds to the present day state of Rajasthan, and which Tod referred to as Rajas'han.

Tod was born in London and educated in Scotland. He joined the East India Company as a military officer and travelled to India in 1799 as a cadet in the Bengal Army. He rose quickly in rank, eventually becoming captain of an escort for an envoy in a Sindian royal court. After the Third Anglo-Maratha War, during which Tod was involved in the intelligence department, he was appointed Political Agent for some areas of Rajputana. His task was to help unify the region under the control of the East India Company. During this period Tod conducted most of the research that he would later publish. Tod was initially successful in his official role, but his methods were questioned by other members of the East India Company. Over time, his work was restricted and his areas of oversight were significantly curtailed. In 1823, owing to declining health and reputation, Tod resigned his post as Political Agent and returned to England.

Back home in England, Tod published a number of academic works about Indian history and geography, most notably Annals and Antiquities of Rajas'han, based on materials collected during his travels. He retired from the military in 1826, and married Julia Clutterbuck that same year. He died in 1835, aged 53.

Tod's major works have been criticised as containing significant inaccuracies and bias, but he is highly regarded in some areas of India, particularly in communities whose ancestors he praised. His accounts of the Rajputs and of India in general had a significant effect on British views of the area for many years.

Life and career

Tod was born in Islington, London, on 20 March 1782.[1][lower-alpha 1] He was the second son for his parents, James and Mary (née Heatly), both of whom came from families of "high standing", according to his major biographer, the historian Jason Freitag.[2][lower-alpha 2] He was educated in Scotland, whence his ancestors came, although precisely where he was schooled is unknown.[4][5] Those ancestors included people who had fought with the King of Scots, Robert the Bruce; he took pride in this fact and had an acute sense of what he perceived to be the chivalric values of those times.[6]

As with many people of Scots descent who sought adventure and success at that time, Tod joined the British East India Company[6] and initially spent some time studying at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich.[7] He left England for India in 1799[lower-alpha 3] and in doing so followed in the footsteps of various other members of his family, including his father, although Tod senior had not been in the Company but had instead owned an indigo plantation at Mirzapur.[8][lower-alpha 4] The young Tod journeyed as a cadet in the Bengal Army, appointment to which position was at the time reliant upon patronage.[10] He was appointed lieutenant in May 1800 and in 1805 was able to arrange his posting as a member of the escort to a family friend who had been appointed as Envoy and Resident to a Sindian royal court. By 1813 he had achieved promotion to the rank of captain and was commanding the escort.[11]

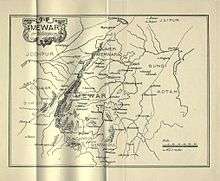

Rather than being situated permanently in one place, the royal court was moved around the kingdom. Tod undertook various topographical and geological studies as it travelled from one area to another, using his training as an engineer and employing other people to do much of the field work. These studies culminated in 1815 with the production of a map which he presented to the Governor-General, the Marquis of Hastings. This map of "Central India" (his phrase)[lower-alpha 5] became of strategic importance to the British as they were soon to fight the Third Anglo-Maratha War.[11] During that war, which ran from 1817 to 1818, Tod acted as a superintendent of the intelligence department and was able to draw on other aspects of regional knowledge which he had acquired while moving around with the court. He also drew up various strategies for the military campaign.[14]

In 1818 he was appointed Political Agent for various states of western Rajputana, in the northwest of India, where the British East India Company had come to amicable arrangements with the Rajput rulers in order to exert indirect control over the area. The anonymous author of the introduction to Tod's posthumously published book, Travels in Western India, says that

Clothed with this ample authority, he applied himself to the arduous task of endeavouring to repair the ravages of foreign invaders who still lingered in some of the fortresses, to heal the deeper wounds inflicted by intestine feuds, and to reconstruct the framework of society in the disorganised states of Rajas'han.[15]

Tod continued his surveying work in this physically-challenging, arid and mountainous area.[16] His responsibilities were extended quickly: initially involving himself with the regions of Mewar, Kota, Sirohi and Bundi, he soon added Marwar to his portfolio and in 1821 was also given responsibility for Jaisalmer.[17] These areas were considered a strategic buffer zone against Russian advances from the north which, it was feared, might result in a move into India via the Khyber Pass. Tod believed that to achieve cohesion it was necessary that the Rajput states should contain only Rajput people, with all others being expelled. This would assist in achieving stability in the areas, thus limiting the likelihood of the inhabitants being influenced by outside forces. According to Ramya Sreenivasan, a researcher of religion and caste in early modern Rajasthan and of colonialism, Tod's "transfers of territory between various chiefs and princes helped to create territorially consolidated states and 'routinised' political hierarchies."[18][19] His successes were plentiful and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography notes that Tod was

so successful in his efforts to restore peace and confidence that within less than a year some 300 deserted towns and villages were repeopled, trade revived, and, in spite of the abolition of transit duties and the reduction of frontier customs, the state revenue had reached an unprecedented amount. During the next five years Tod earned the respect of the chiefs and people, and was able to rescue more than one princely family, including that of the ranas of Udaipur, from the destitution to which they had been reduced by Maratha raiders.[4]

Tod was not, however, universally respected in the East India Company. His immediate superior, David Ochterlony, was unsettled by Tod's rapid rise and frequent failure to consult with him. One Rajput prince objected to Tod's close involvement in the affairs of his state and succeeded in persuading the authorities to remove Marwar from Tod's area of influence. In 1821 his favouritism towards one party in a princely dispute, contrary to the orders given to him, gave rise to a severe reprimand and a formal restriction of his ability to operate without consulting Ochterlony, as well as the removal of Kota from his charge. Jaisalmer was then taken out of his sphere of influence in 1822, as official concerns grew regarding his sympathy for the Rajput princes. This and other losses of status, such as the reduction in the size of his escort, caused him to believe that his personal reputation and ability to work successfully in Mewar, by now the one area still left to him, was too diminished to be acceptable. He resigned his role as Political Agent in Mewar later that year, citing ill health.[17] Reginald Heber, the Bishop of Calcutta, commented that

His misfortune was that, in consequence of favouring native princes so much, the government of Calcutta were led to suspect him of corruption, and consequently to narrow his powers and associate other officers with him in his trust, till he was disgusted and resigned his place. They are now satisfied, I believe, that their suspicions were groundless.[4]

In February 1823, Tod left India for England, having first travelled to Bombay by a circuitous route for his own pleasure.[20]

During the last years of his life Tod talked about India at functions in Paris and elsewhere across Europe. He also became a member of the newly established Royal Asiatic Society in London, for whom he acted for some time as librarian.[lower-alpha 6] He suffered an apoplectic fit in 1825 as a consequence of overwork,[22] and retired from his military career in the following year,[lower-alpha 7] soon after he had been promoted to lieutenant-colonel. His marriage to Julia Clutterbuck (daughter of Henry Clutterbuck) in 1826 produced three children – Grant Heatly Tod-Heatly, Edward H. M. Tod and Mary Augusta Tod – but his health, which had been poor for much of his life,[24] was declining. Having lived at Birdhurst, Croydon, from October 1828, Tod and his family moved to London three years later. He spent much of the last year of his life abroad in an attempt to cure a chest complaint and died on 18 November 1835[4] soon after his return to England from Italy. The cause of death was an apoplectic fit sustained on the day of his wedding anniversary, although he survived for a further 27 hours. He had moved into a house in Regent's Park earlier in that year.[20][25]

Worldview

According to Theodore Koditschek, whose fields of study include historiography and British imperial history, Tod saw the Rajputs as "natural allies of the British in their struggles against the Mughal and Maratha states".[26] Norbert Peabody, an anthropologist and historian, has gone further, arguing that "maintaining the active support of groups, like the Rajputs for example, was not only important in meeting the threat of indigenous rivals but also in countering the imperial aspirations of other European powers."[27] He stated that some of Tod's thoughts were "implicated in [British] colonial policy toward western India for over a century."[28]

Tod favoured the then-fashionable concept of Romantic nationalism. Influenced by this, he thought that each princely state should be inhabited by only one community and his policies were designed to expel Marathas, Pindaris and other groups from Rajput territories. It also influenced his instigation of treaties that were intended to redraw the territorial boundaries of the various states. The geographical and political boundaries before his time had in some cases been blurred, primarily due to local arrangements based on common kinship, and he wanted a more evident delineation of the entities,[lower-alpha 8] He was successful in both of these endeavours.[31]

Tod was unsuccessful in implementing another of his ideas, which was also based on the ideology of Romantic nationalism. He believed that the replacement of Maratha rule with that of the British had resulted in the Rajputs merely swapping the onerous overlordship of one government for that of another. Although he was one of the architects of indirect rule, in which the princes looked after domestic affairs but paid tribute to the British for protection in foreign affairs, he was also a critic of it. He saw the system as one that prevented achievement of true nationhood, and therefore, as Peabody describes, "utterly subversive to the stated goal of preserving them as viable entities."[31] Tod wrote in 1829 that the system of indirect rule had a tendency to "national degradation" of the Rajput territories and that this undermined them because

Who will dare to urge that a government, which cannot support its internal rule without restriction, can be national? That without power unshackled and unrestrained by exterior council or espionage, it can maintain its self-respect? This first of feelings these treaties utterly annihilate. Can we suppose such denationalised allies are to be depended upon in emergencies? Or, if allowed to retain a spark of their ancient moral inheritance, that it will not be kindled into a flame against us when opportunity offers?[32]

There was a political aspect to his views: if the British recast themselves as overseers seeking to re-establish lost Rajput nations, then this would at once smooth the relationship between those two parties and distinguish the threatening, denationalising Marathas from the paternal, nation-creating British. It was an argument that had been deployed by others in the European arena, including in relation to the way in which Britain portrayed the imperialism of Napoleonic France as denationalising those countries which it conquered, whereas (it was claimed) British imperialism freed people; William Bentinck, a soldier and statesmen who later in life served as Governor-General of India, noted in 1811 that "Bonaparte made kings; England makes nations".[33] However, his arguments in favour of granting sovereignty to the Rajputs failed to achieve that end,[31] although the frontispiece to volume one of his Annals did contain a plea to the then English King George IV to reinstate the "former independence" of the Rajputs.[34]

While he viewed the Muslim Mughals as despotic and the Marathas as predatory,[35][lower-alpha 9] Tod saw the Rajput social systems as being similar to the feudal system of medieval Europe, and their traditions of recounting history through the generations as similar to the clan poets of the Scottish Highlanders. There was, he felt, a system of checks and balances between the ruling princes and their vassal lords, a tendency for feuds and other rivalries, and often a serf-like peasantry.[37] The Rajputs were, in his opinion, on the same developmental trajectory that nations such as Britain had followed. His ingenious use of these viewpoints later enabled him to promote in his books the notion that there was a shared experience between the people of Britain and this community in a distant, relatively unexplored area of the empire. He speculated that there was a common ancestor shared by the Rajputs and Europeans somewhere deep in prehistory and that this might be proven by comparison of the commonality in their history of ideas, such as myth and legend. In this he shared a contemporary aspiration to prove that all communities across the world had a common origin.[38][39][40] There was another appeal inherent in a feudal system, and it was not unique to Tod: the historian Thomas R. Metcalf has said that

In an age of industrialism and individualism, of social upheaval and laissez-faire, marked by what were perceived as the horrors of continental revolution and the rationalist excesses of Benthamism, the Middle Ages stood forth as a metaphor for paternalist ideals of social order and proper conduct ... [T]he medievalists looked to the ideals of chivalry, such as heroism, honour and generosity, to transcend the selfish calculation of pleasure and pain, and recreate a harmonious and stable society.[41]

Above all, the chivalric ideal viewed character as more worthy of admiration than wealth or intellect, and this appealed to the old landed classes at home as well as to many who worked for the Indian Civil Service.[41]

In the 1880s, Alfred Comyn Lyall, an administrator of the British Raj who also studied history, revisited Tod's classification and asserted that the Rajput society was in fact tribal, based on kinship rather than feudal vassalage. He had previously generally agreed with Tod, who acknowledged claims that blood-ties played some sort of role in the relationship between princes and vassals in many states. In shifting the emphasis from a feudal to a tribal basis, Lyall was able to deny the possibility that the Rajput kingdoms might gain sovereignty. If Rajput society was not feudal, then it was not on the same trajectory that European nations had followed, thereby forestalling any need to consider that they might evolve into sovereign states. There was thus no need for Britain to consider itself to be illegitimately governing them.[37][42]

Tod's enthusiasm for bardic poetry reflected the works of Sir Walter Scott on Scottish subjects, which had a considerable influence both on British literary society and, bearing in mind Tod's Scottish ancestry, on Tod himself. Tod reconstructed Rajput history on the basis of the ancient texts and folklore of the Rajputs, although not everyone – for example, the polymath James Mill – accepted the historical validity of the native works. Tod also used philological techniques to reconstruct areas of Rajput history that were not even known to the Rajputs themselves, by drawing on works such as the religious texts known as Puranas.[38]

Publications

Koditschek says that Tod "developed an interest in triangulating local culture, politics and history alongside his maps",[26] and Metcalf believes that Tod "ordered [the Rajputs'] past as well as their present" while working in India.[43] During his time in Rajputana, Tod was able to collect materials for his Annals and Antiquities of Rajas'han, which detailed the contemporary geography and history of Rajputana and Central India along with the history of the Rajput clans who ruled most of the area at that time. Described by historian Crispin Bates as "a romantic historical and anecdotal account"[44] and by David Arnold, another historian, as a "travel narrative" by "one of India's most influential Romantic writers",[45] the work was published in two volumes, in 1829 and 1832,[lower-alpha 10] and included illustrations and engravings by notable artists such as the Storers, Louis Haghe and either Edward or William Finden.[49] He had to finance publication himself: sales of works on history had been moribund for some time and his name was not particularly familiar either at home or abroad.[50] Original copies are now scarce, but they have been reprinted in many editions. The version published in 1920, which was edited by the orientalist and folklorist William Crooke, is significantly editorialised.[51]

Freitag has argued that the Annals "is first and foremost a story of the heroes of Rajasthan ... plotted in a certain way – there are villains, glorious acts of bravery, and a chivalric code to uphold".[52] So dominant did Tod's work become in the popular and academic mind that they largely replaced the older accounts upon which Tod based much of his content, notably the Prithvirãj Rãjo and the Nainsi ri Khyãt.[53] Kumar Singh, of the Anthropological Survey of India, has explained that the Annals were primarily based on "bardic accounts and personal encounters" and that they "glorified and romanticised the Rajput rulers and their country" but ignored other communities.[54]

One aspect of history that Tod studied in his Annals was the genealogy of the Chathis Rajkula (36 royal races), for the purpose of which he took advice on linguistic issues from a panel of pandits, including a Jain guru called Yati Gyanchandra.[55] He said that he was "desirous of epitomising the chronicles of the martial races of Central and Western India" and that this necessitated study of their genealogy. The sources for this were Puranas held by the Rana of Udaipur.[56]

Tod also submitted archæological papers to the Royal Asiatic Society's Transactions series. He was interested in numismatics as well, and he discovered the first specimens of Bactrian and Indo-Greek coins from the Hellenistic period following the conquests of Alexander the Great, which were described in his books. These ancient kingdoms had been largely forgotten or considered semi-legendary, but Tod's findings confirmed the long-term Greek presence in Afghanistan and Punjab. Similar coins have been found in large quantities since his death.[25][57]

In addition to these writings, he produced a paper on the politics of Western India that was appended to the report of the House of Commons committee on Indian affairs, 1833.[4] He had also taken notes on his journey to Bombay and collated them for another book, Travels in Western India.[20] That book was published posthumously in 1839.

Reception

Criticism of the Annals came soon after publication. The anonymous author of the introduction to his posthumously published Travels states that

The only portions of this great work which have experienced anything like censure are those of a speculative character, namely, the curious Dissertation on the Feudal System of the Rajpoots, and the passages wherein the Author shows too visible a leaning towards hypotheses identifying persons, as well as customs, manners, and superstitions, in the East and the West, often on the slender basis of etymological affinities.[58]

Further criticism followed. Tod was an officer of the British imperial system, at that time the world's dominant power. Working in India, he attracted the attention of local rulers who were keen to tell their own tales of defiance against the Mughal empire. He heard what they told him but knew little of what they omitted. He was a soldier writing about a caste renowned for its martial abilities, and he was aided in his writings by the very people whom he was documenting. He had been interested in Rajput history prior to coming into contact with them in an official capacity, as administrator of the region in which they lived. These factors, says Freitag, contribute to why the Annals were "manifestly biased".[59] Freitag argues that critics of Tod's literary output can be split into two groups: those who concentrate on his errors of fact and those who concentrate on his failures of interpretation.[6]

Tod relied heavily on existing Indian texts for his historical information and most of these are today considered unreliable. Crooke's introduction to Tod's 1920 edition[lower-alpha 11] of the Annals recorded that the old Indian texts recorded "the facts, not as they really occurred, but as the writer and his contemporaries supposed that they occurred."[60] Crooke also says that Tod's "knowledge of ethnology was imperfect, and he was unable to reject the local chronicles of the Rajputs."[61] More recently, Robin Donkin, a historian and geographer, has argued that, with one exception, "there are no native literary works with a developed sense of chronology, or indeed much sense of place, before the thirteenth century", and that researchers must rely on the accounts of travellers from outside the country.[62][lower-alpha 12]

Tod's work relating to the genealogy of the Chathis Rajkula was criticised as early as 1872, when an anonymous reviewer in the Calcutta Review said that

It seems a pity that Tod's classification of 36 royal races should be accepted as anything but a purely ornamental arrangement, founded as it was on lists differing considerably both in the numbers and names of the tribes included in it, and containing at least two tribes, the Jats and Gujars, with whom the Rajputs do not even generally intermarry.[63]

Other examples of dubious interpretations made by Tod include his assertions regarding the ancestry of the Mohil Rajput clan when, even today, there is insufficient evidence to prove his point.[64] He also mistook Rana Kumbha, a ruler of Mewar in the fifteenth century, as being the husband of the princess-saint Mira Bai[65] and misrepresented the story of the queen Padmini.[66] The founder of the Archaeological Survey of India, Alexander Cunningham, writing in 1885, noted that Tod had made "a whole bundle of mistakes" in relation to the dating of the Battle of Khanwa,[67] and Crooke notes in his introduction to the 1920 edition that Tod's "excursions into philology are the diversions of a clever man, not of a trained scholar, but interested in the subject as an amateur."[68] Michael Meister, an architectural historian and professor of South Asia Studies, has commented that Tod had a "general reputation for inaccuracy ... among Indologists by late in the nineteenth century", although the opinion of those Indologists sometimes prevented them from appreciating some of the useful aspects in his work.[69] That reputation persists, with one modern writer, V. S. Srivastava of Rajasthan's Department of Archaeology and Museums, commenting that his works "are erroneous and misleading at places and they are to be used with caution as a part of sober history".[70]

In its time, Tod's work was influential even among officials of the government, although it was never formally recognised as authoritative. Andrea Major, who is a cultural and colonial historian, has commented on a specific example, that of the tradition of sati (ritual immolation of a widow):

The overly romanticised image of Rajasthan, and of the Rajput sati, that Tod presented came to be extremely influential in shaping British understanding of the rite's Rajput context. Though Tod does make a point of denouncing sati as a cruel and barbarous custom, his words are belied by his treatment of the subject in the rest of the Annals. ... Tod's image of the Rajput sati as the heroic equivalent of the Rajput warrior was one that caught the public imagination and which exhibited surprising longevity.[71]

The romantic nationalism that Tod espoused was used by Indian nationalist writers, especially those from the 1850s, as they sought to resist British control of the country. Works such as Jyotirindranath Tagore's Sarojini ba Chittor Akrama and Girishchandra Ghosh's Ananda Raho retold Tod's vision of the Rajputs in a manner to further their cause.[34] Other works which drew their story from Tod's works include Padmini Upakhyan (1858) by Rangalal Banerjee and Krishna Kumari (1861) by Michael Madhusudan Dutt.[72]

In modern-day India, he is still revered by those whose ancestors he documented in good light. In 1997, the Maharana Mewar Charitable Foundation instituted an award named after Tod and intended it to be given to modern non-Indian writers who exemplified Tod's understanding of the area and its people.[73] In other recognition of his work in Mewar Province, a village has been named Todgarh,[74] and it has been claimed that Tod was in fact a Rajput as an outcome of the process of karma and rebirth.[75] Freitag describes the opinion of the Rajput people

Tod, here, is not about history as such, but is a repository for "truth" and "splendor" ... The danger, therefore, is that the old received wisdom – evident and expressed in the work of people like Tod – will not be challenged at all, but will become much more deeply ingrained.[59]

Furthermore, Freitag points out that "the information age has also anointed Tod as the spokesman for Rajasthan, and the glories of India in general, as attested by the prominent quotations from him that appear in tourism related websites."[76]

Works

Published works by James Tod include:

- Tod, James (1824). "Translation of a Sanscrit Inscription, Relative to the Last Hindu King of Delhi, with Comments Thereon". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 1 (1): 133–154.

- Tod, James (1826). "Comments on an Inscription upon Marble, at Madhucarghar; And Three Grants Inscribed on Copper, Found at Ujjayani". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 1 (2): 207–229.

- Tod, James (1826). "An Account of Greek, Parthian, and Hindu Medals, Found in India". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 1 (2): 313–342.

- Tod, James (1829). "On the Religious Establishments of Mewar". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2 (1): 270–325. doi:10.1017/S0950473700001415.

- Tod, James (1829). "Remarks on Certain Sculptures in the Cave Temples of Ellora". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2 (1): 328–339. doi:10.1017/S0950473700001439.

- Tod, James (1829). Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han or the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India, Volume 1. London: Smith, Elder.

- Tod, James (1830). "Observations on a Gold Ring of Hindu Fabrication found at Montrose in Scotland". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2 (2): 559–571.

- Tod, James (1831). "Comparison of the Hindu and Theban Hercules, illustrated by an ancient Hindu Intaglio". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 3 (1): 139–159.

- Tod, James (1832). Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han or the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India, Volume 2. London: Smith, Elder.

- Tod, James (1839). Travels in Western India. London: W. H. Allen.

Later editions

- Tod, James (1920). Crooke, William, ed. Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han or the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India. 1. London: Humphrey Milford / Oxford University Press.

- Tod, James (1920). Crooke, William, ed. Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han or the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India. 2. London: Humphrey Milford / Oxford University Press.

- Tod, James (1920). Crooke, William, ed. Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han or the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India. 3. London: Humphrey Milford / Oxford University Press.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Although 20 March 1782 is generally used as his date of birth, documentation for his christening states it as 19 March.[1]

- ↑ As of 2009, when his biography of Tod was published, Jason Freitag was not aware of any other book-length study of Tod. Freitag received hospitality from His Highness Arvind Singh Mewar, of the Mewar royal family, during the process that resulted in publication of his work. Much of the content of Freitag's book appears in his earlier PhD thesis.[3]

- ↑ Freitag says Tod left for India in 1798 in his 2007 work, and in 1799 in his 2009 work.

- ↑ Suetonius Grant Heatly was another of Tod's relatives who spent time in India. He was an uncle and, together with one or perhaps two other colleagues from the East India Company, he is the first documented instance of someone attempting the commercial extraction of coal in the country. Suetonius Heatly died before James Tod entered the service of the Company; another uncle – Suetonius's brother, Patrick Heatly – did not die until 1834 and also worked for the Company both in India and in London.[9]

- ↑ Accounts written during Tod's lifetime say that he also coined the term Rajasthan,[12] although it appears in an inscription of 1708.[13]

- ↑ Fellowships of the Royal Asiatic Society appear not to have existed at the time of his death in 1835, but at that point he was a member of the Society's Oriental Translation Committee.[21]

- ↑ The introduction to Tod's Travels in Western India gives the date of his retirement from military service as 28 June 1825, but recent sources use 1826.[23]

- ↑ Romantic nationalism found much support as an alternative theory to civic nationalism and was a force behind the nineteenth-century unifications of Germany and Italy.[30]

- ↑ It had been a commonly held view since at least the time of the Crusades that Muslim rulers were despotic because it was thought that Islamic beliefs promoted such tendencies; in the words of Alexander Dow, it was "peculiarly calculated for despotism".[36]

- ↑ The Annals were sold at a price of £4. 14s. 6d. per volume,[46][47] and the Travels sold for £3. 13s. 6d.[48]

- ↑ The 1920 edition of the Annals was produced in three volumes rather than the original two volumes.

- ↑ The exception is Kalhana's Rajatarangini.

Citations

- 1 2 Freitag (2009), p. 33.

- ↑ Freitag (2001), p. 29.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), p. 9, n. 4 p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wheeler & Stearn, (2004) Tod, James (1782–1835).

- ↑ Freitag (2009), p. 35.

- 1 2 3 Freitag (2007), p. 49.

- ↑ Tod (1839), p. xviii.

- ↑ Freitag (2001), p. 30.

- ↑ Manners & Williamson (1920), p. 180.

- ↑ Freitag (2001), p. 31.

- 1 2 Freitag (2009), pp. 34–36.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), n. 17 p. 36.

- ↑ Gupta & Bakshi (2008), p. 142.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), p. 37.

- ↑ Tod (1839), p. xxxiii.

- ↑ Gupta & Bakshi (2008), p. 132.

- 1 2 Freitag (2009), pp. 37–40.

- ↑ Sreenivasan (2007), pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Peabody (1996), p. 203.

- 1 2 3 Freitag (2009), p. 40.

- ↑ Royal Asiatic Society (1835), Appendix, pp. xlvii–liv, lxi.

- ↑ Tod (1839), p. xlvii.

- ↑ Tod (1839), p. l.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), p. 41.

- 1 2 The Gentleman's Magazine (February 1836), Obituary, pp. 203–204.

- 1 2 Koditschek (2011), p. 68.

- ↑ Peabody (1996), p. 204.

- ↑ Peabody (1996), p. 185.

- ↑ British Library, Residency.

- ↑ Hutchinson (2005), pp. 49–50.

- 1 2 3 Peabody (1996), pp. 206–207.

- ↑ Tod (1829), Vol. 1., pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Peabody (1996), p. 209.

- 1 2 Peabody (1996), p. 217.

- ↑ Peabody (1996), p. 212.

- ↑ Metcalf (1997), p. 8.

- 1 2 Metcalf (1997), pp. 73–74.

- 1 2 Sreenivasan (2007), pp. 130–132.

- ↑ Koditschek (2011), p. 69.

- ↑ Tod (1829), Vol. 1., pp. 72–74.

- 1 2 Metcalf (1997), p. 75.

- ↑ Peabody (1996), p. 215.

- ↑ Metcalf (1997), p. 73.

- ↑ Bates (1995), p. 242.

- ↑ Arnold (2004), p. 343.

- ↑ Edinburgh Review (1830), Advertisement, p. 13.

- ↑ Asiatic Journal (1832), New Publications, p. 80.

- ↑ British Magazine (1839), New Books, p. 359.

- ↑ The Literary Gazette and Journal (1829), Sights of books, p. 536.

- ↑ Tod (1839), pp. li–lii.

- ↑ Peabody (1996), p. 187.

- ↑ Freitag (2001), p. 20.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), p. 10.

- ↑ Singh (1998), p. xvi.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), pp. 112, 120, 164.

- ↑ Tod (1829), Vol. 1., p. 17.

- ↑ Wilson (1998), pp. 4–10.

- ↑ Tod (1839), pp. lii–liii.

- 1 2 Freitag (2009), pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Crooke (Annals, 1920 ed.), introduction to Vol. 1., p. xxx.

- ↑ Crooke (Annals, 1920 ed.), introduction to Vol. 1., p. xxxi.

- ↑ Donkin (1998), p. 152.

- ↑ Calcutta Review (1872), The Hindu Castes, p. 386.

- ↑ Handa (1981), p. RA-120.

- ↑ Nilsson (1997), pp. 12, 19.

- ↑ Sreenivasan (2007), p. 140.

- ↑ Cunningham (1885), p. 97.

- ↑ Crooke (Annals, 1920 ed.), introduction to Vol. 1., p. xxxix.

- ↑ Meister (1981), p. 57.

- ↑ Srivastava (1981), p. 120.

- ↑ Major (2010), p. 33.

- ↑ Mehrotra (2006), pp. 7-8

- ↑ Freitag (2009), pp. 2, 4.

- ↑ Sebastian (2010).

- ↑ Freitag (2009), n. 2 p. 2.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), pp. 8–9.

Bibliography

- "Advertisement". The Edinburgh Review. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green; Edinburgh: Adam Black. CI. April 1830. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- "Appendix: Rules and Regulations of the Society; Members of the Oriental Translation Committee". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. London: John W. Parker. 2. 1835. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- Arnold, David (2004). "Deathscapes: India in an age of Romanticism and empire, 1800–1856". Nineteenth-Century Contexts. Abingdon: Routledge. 26 (4). Retrieved 2012-01-09. (Subscription required).

- Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter. The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1885). Report of a Tour in Eastern Rajputana in 1882–83. Archaeological Survey of India. XX. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India. Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- Donkin, Robin A. (1998). "Beyond price: pearls and pearl-fishing: origins to the age of discoveries". Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. 224. ISBN 978-0-87169-224-5. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- East India Company (May–August 1832). "New publications". Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany. New Series. London: Wm. H. Allen & Co. 8 (29). Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- Freitag, Jason (2001). The power which raised them from ruin and oppression: James Tod, historiography, and the Rājpūt ideal. New York: Columbia University Libraries. Retrieved 2011-10-05. (Subscription required).

- Freitag, Jason (2007). "Travel, history, Politics, Heritage: James Tod's "Personal Narrative"". In Henderson, Carol E.; Weisgrau, Maxine K. Raj rhapsodies: tourism, heritage and the seduction of history. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-7067-4. Retrieved 2011-08-08.

- Freitag, Jason (2009). Serving empire, serving nation: James Tod and the Rajputs of Rajasthan. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17594-5. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- Gupta, R. K.; Bakshi, S. R. (2008). Studies In Indian History: Rajasthan Through The Ages The Heritage Of Rajputs. 1. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 81-7625-841-5. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- Handa, Devendra (1981). "An interesting inscribed relief dated S. 1010 from Ladmun". In Prakash, Satya; Śrivastava, Vijai Shankar. Cultural contours of India: Dr. Satya Prakash felicitation volume. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-0-391-02358-1. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- Hutchinson, John (2005). Nations as zones of conflict. London: SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-5727-0. Retrieved 2011-08-11.

- Koditschek, Theodore (2011). Liberalism, Imperialism, and the Historical Imagination: Nineteenth Century Visions of a Greater Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76791-0. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- Major, Andrea (2010). Sovereignty and social reform in India: British colonialism and the campaign against Sati, 1830–1860. Abingdon: Routledge (Taylor & Francis e-Library). ISBN 978-0-415-58050-2. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- Manners, Victoria; Williamson, G. C. (1920). John Zoffany, R.A. his life and works : 1735–1810. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head. Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna (2006). An illustrated history of Indian literature in English. India: Permanent Black. ISBN 978-81-7824-151-7.

- Meister, Michael W. (1981). "Forest and Cave: Temples at Candrabhāgā and Kansuāñ". Archives of Asian Art. New York: University of Hawai'i Press for the Asia Society. 34: 56–73. ISSN 1944-6497. JSTOR 20111117. (Subscription required).

- Metcalf, Thomas R. (1997). Ideologies of the Raj. The New Cambridge History of India, Volume 4 (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58937-6. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- "New Books". The British Magazine. London: J. Petheram. XVI. 1 September 1839. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- Nilsson, Usha (1997). Mira Bai. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-0411-9. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- "Obituary". The Gentleman's Magazine. New Series. London: William Pickering; John Bowyer Nichols and Son. 5. February 1836. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- Peabody, Norbert (1996). "Tod's Rajast'han and the Boundaries of Imperial Rule in Nineteenth-Century India". Modem Asian Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 30 (1): 185–220. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0001413X. ISSN 0026-749X. Retrieved 2012-02-08. (Subscription required).

- Saran, Richard; Ziegler, Norman (2001). The Mertiyo Rathors of Merto, Rajasthan: Select Translations Bearing on the History of a Rajput Family, 1462–1660, Volumes 1–2. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-89148-085-3.

- "Residency, Oodeypore". London: British Library. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- Sebastian, Sunny (4 October 2010). "Rajasthan now plans an eco-train safari". The Hindu. Jaipur. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- "Sights of books". The Literary Gazette and Journal. London: The Literary Gazette (656). 15 August 1829. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- Singh, Kumar Suresh (1998). People of India: Rajasthan, Part 1. Volume 38 of People of India. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-766-1. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- Sreenivasan, Ramya (2007). The many lives of a Rajput queen: heroic pasts in India c. 1500–1900. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98760-6. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- Srivastava, Vijai Shankar (1981). "The story of archaeological, historical and antiquarian researches in Rajasthan before independence". In Prakash, Satya; Śrivastava, Vijai Shankar. Cultural contours of India: Dr. Satya Prakash felicitation volume. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-0-391-02358-1. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- "The Hindu Castes". Calcutta Review. Calcutta: Thomas S. Smith. LV (CX). 1872. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- Tod, James (1920) [1829]. Crooke, William, ed. Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han or the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India, Volume 1. London: Humphrey Milford / Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- Tod, James (1839). Travels in Western India. London: W. H. Allen. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- Wheeler, Stephen; Stearn, Roger T. (2004). "Tod, James (1782–1835)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2012-02-08. (Subscription or UK public library membership required).

- Wilson, Horace Hayman (1998) [1841]. Ariana antiqua: a descriptive account of the antiquities and coins of Afghanistan (Reprinted ed.). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1189-4. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

Further reading

- East India Company (August 1829). "Review of books: Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han". Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany. London: Wm. H. Allen & Co. 28 (164): 187–198.

- East India Company (May–August 1832). "Colonel Tod's History of Rajpootana (book review, volume 2)". Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany. New Series. London: Wm. H. Allen & Co. 8 (29): 57–66.

- Ojha, Gaurishankar Hirachand (2002). Suprasiddha itihaskara Karnala James Toda ka jivana charitra (in Hindi). Jodhpur: Rajasthani Granthagara.

- "Reviews". The Athenaeum. London: The Athenaeum (613): 555–558. 27 July 1839. – A partial review of Travels, concluded in the subsequent issue.

- Tillotson, Giles, ed. (2008). James Tod's Rajasthan: The Historian and His Collections. Mumbai: Radhika Sabavala for Marg Publications on behalf of the National Centre for the Performing Arts. ISBN 81-85026-80-7.

- "Treaty with the Rajah of Boondee". Treaties and engagements with native princes and states in India 1817 and 1818. London: India Office. 1824. p. xci. – an example of a treaty in which Tod was involved.

- Vaishishtha, Vijay Kumar (1992). "James Tod as a Historian". In Sharma, Gopi Nath; Bhatnagar, V. S. The Historians and sources of history of Rajasthan. Jaipur: Centre for Rajasthan Studies, University of Rajasthan.