Annular tropical cyclone

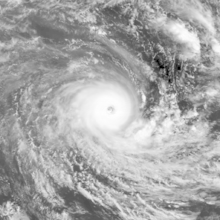

An annular tropical cyclone is a subset of tropical cyclones that features a large, symmetric eye surrounded by a thick and uniform ring of intense convection, often having a relative lack of discrete rainbands. As a result, the appearance of an annular tropical cyclone can be referred to as akin to a truck tire or doughnut.[1] Annular characteristics can be attained as tropical cyclones intensify; however, outside of the processes that drive the transition from asymmetric systems to annular systems and the abnormal resistance to negative environmental factors found in storms with annular features, annular tropical cyclones behave similarly to asymmetric storms. Most research related to annular tropical cyclones is limited to satellite imagery and aircraft reconnaissance as the conditions thought to give rise to annular characteristics normally occur over water well removed from landmasses where surface observations are possible.

Characteristics and identification

The annular hurricane was first defined as a subset of tropical cyclones by John Knaff of Colorado State University and James Kossin of the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 2002 by use of infrared satellite imagery, which serves as the visual means of ascertaining annular characteristics within tropical cyclone. Knaff and Kossin defined an annular tropical cyclone as a tropical cyclone that maintains both average or larger-than-average eye surrounded by deep convection containing the storm's inner core and a lack of convection occurring outside of the central dense overcast for at least three hours. As a result, annular storms lack the rainbands characteristic of typical tropical cyclone. These features lend the storm an axisymmetric appearance common to annular tropical cyclones. However, this definition is only applicable while a storm maintains these characteristics—when and while a storm is not feature annular characteristics, the tropical cyclone is considered asymmetric. In addition to the primary defining characteristics, the diurnal pulsation the cirrus cloud canopy associated with outflow is subdued once storms become annular.[1]

Although tropical cyclones can achieve annular characteristics across a wide spectrum of intensities, annular storms are typically strong tropical cyclones, with average maximum sustained windspeeds of 108 kn (200 km, 124 mph). In addition, storms attaining annular characteristics are less prone to weakening as a result of negative environmental factors. Annular cyclones can maintain their respective peak intensities for extended periods of time unlike their asymmetric counterparts. Following peak intensity, such systems will tend to gradually taper off. This unusual intensity persistence makes their future intensities difficult to forecast and often results in large forecast errors. In an analysis of hurricanes in the East Pacific and North Atlantic between 1995 and 1999, Knaff and Kossin observed that the National Hurricane Center underestimated the intensity of annular hurricanes 72 hours out by 18.9 kn (35.0 km, 21.7 mph).[1]

An algorithm for identification of annular tropical cyclones in real-time by objective criteria has been developed, and shows some power, but is not yet operational.[2]

Transition from asymmetric cyclones and necessary conditions

Tropical cyclones can become annular as a result of eyewall mesovortices mixing the strong winds found in the eyewalls of storms with the weak winds of the eye, which helps to expand the eye. In addition, this process helps to make the equivalent potential temperature (often referred to as theta-e or ) within the eye relatively uniform. This transition takes roughly 24 hours to complete and can be considered a type of eyewall replacement cycle. Winds have also been found to decrease in a stairstep like fashion within the radius of maximum wind, which may indicate that more wind is mixed between the eye and eyewall as cyclones strengthen, which helps to explain why annular characteristics are generally exclusive to storms of higher intensities.[1]

The intensity of annular systems is typically greater than 83.5% of the maximum potential intensity, suggesting that the conditions in which storms gain annular characteristics are generally conducive for tropical cyclone persistence. Annular tropical cyclones also necessitate low wind shear, and of the storms in the East Pacific and North Atlantic studied by Knaff and Kossin, all exhibited easterly winds and cold air in the upper troposphere, suggesting that the conditions that give rise to annular tropical cyclones are most optimal towards the equatorward side of a subtropical ridge and within the tropics. However, warmer sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are not a necessity for annular tropical cyclones, with annular characteristics developing only within a narrow range of modest SSTs ranging from 25.4 °C–28.5 °C (77.7 °F–83.3 °F).

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Knaff, John A.; Kossin, James P. (April 2003). "Annular Hurricanes" (PDF). Weather and Forecasting. Fort Collins, Colorado: American Meteorological Society. 18 (2): 204–223. Bibcode:2003WtFor..18..204K. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2003)018<0204:AH>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ↑ Knaff, John A.; Cram, T.A.; Schumacher, A.B.; Kossin, J.P.; DeMaria, M. (February 2008). "Objective Identification of Annular Hurricanes" (abstract). Weather and Forecasting. American Meteorological Society. 23 (1): 17–28. Bibcode:2008WtFor..23...17K. doi:10.1175/2007WAF2007031.1.