Anthropomorphism in Kabbalah

| Part of a series on | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kabbalah | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

Concepts |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Role

|

|||||||||||||||||||

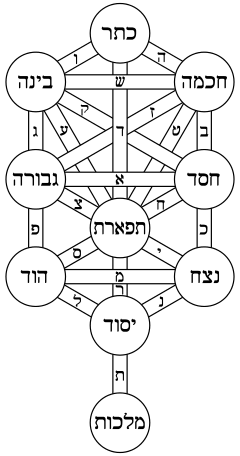

Kabbalah, the central system in Jewish mysticism, uses subtle anthropomorphic analogies and metaphors to describe God in Judaism. These include male-female influences in the Divine. Kabbalists repeatedly warn and stress the need to divorce their notions from any corporeality, dualism, plurality, or spatial and temporal connotations. As "the Torah speaks in the language of Man",[1] the empirical terms are necessarily imposed upon man's experience in this world. Once the analogy is described, its limitations are then related to, stripping the kernel of its husk, to arrive at a truer conception.

Due to the danger of impure material analogy, Kabbalists traditionally restricted oral transmission to close circles, with sincere motives, advanced learning and elite preparation, while also seeking possible dissemination from the 16th century to further Messianic preparation. Understanding Kabbalah through its unity with complete mainstream Talmudic, Halachic and philosophical proficiency was a traditional prerequisite to avoid the false dangers. They attributed 17th-18th century Sabbatean mystical heresies to false corporeality of Kabbalah through unworthy motives. Later Hasidic thought saw its communal popularisation as a safeguard against esoteric corporeality, by its new internalisation of Jewish mysticism through the psychological spiritual experience of man.[2]

Kabbalah emerged parallel to, and soon after, the rationalist tradition of Medieval Jewish philosophy. Maimonides articulated normative Jewish theology in his philosophical stress against any false corporeal interpretation of references to God in the Hebrew Bible and Rabbinic literature, encapsulated in his 3rd principle of faith[3] and legal codification of Monotheism. He formulated the philosophical transcendence of the Godhead through negative theology. Kabbalists agreed with this but gave a radical, different immanent approach to God by relating to Divine emanations. These involved Medieval Zoharic notions of Divine attributes and male-female powers, recast though 16th century Lurianism as cosmic Withdrawal, exile-redemption and Divine Personas, further emphasising the non-corporeal nature of its personified doctrines which became dominant in early-modern Judaism.[4] Nonetheless, Kabbalists carefully chose their terminology to denote subtle connotations and profound relationships in the Divine spiritual influences. More accurately, as they describe the emanation of the Material world from the Spiritual realms, the analogous anthropomorphisms and material metaphors themselves derive through cause and effect from their precise root analogies on High.

Athropomorphisms and metaphors

The consciousness of Atzilut

The Man metaphor

The metaphor of sexuality in Kabbalah

Divine Names and Sephirot in Meditative Kabbalah

See also

- God in Judaism

- Godhead in Judaism

- Negative theology in Judaism

- Idolatry in Judaism

- Prophecy

- Song of Songs

- Aggadah

- Four who entered the Pardes

- Merkabah mysticism

- Sephirot

- Shechinah

- Tohu and Tikun

- Partzufim

- Deveikut

- Jewish meditation

- Hasidic internalisation of Kabbalah

- Generational ascent in Kabbalah

- Sabbatean mystical heresies

- Dor Daim

Notes

- ↑ Talmud Berachot 31b and other sources in Chazal

- ↑ The Great Maggid, Jacob Immanuel Schochet, Kehot. Footnote quoting the Baal Shem Tov in the name of Menachem Mendel Schneersohn (1789-1866) directing the layman against learning classical Kabbalah, outside its inner Hasidic explanation. The error of Sabbateanism and its offshoot Frankism arose from the unworthy corporeal misinterpretation of Kabbalah

- ↑ "I believe with perfect faith that the Creator, Blessed be His Name, has no body, and that He is free from all the properties of matter, and that there can be no (physical) comparison to Him whatsoever," Maimonides' 3rd principle of faith

- ↑ "The Lurianic Kabbalah was the last religious movement in Judaism the influence of which became preponderant among all sections of Jewish people and in every country of the Diaspora, without exception." Gershom Scholem Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism 3rd edition 1955, Thames & Hudson, pages 285-6

External links

- True Monotheism Kabbalistic understanding of the absolute Unity of Divine manifestations, from inner.org