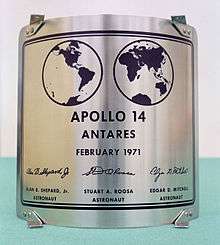

Apollo 14

Shepard poses next to the American flag on the Moon during Apollo 14 | |||||

| Mission type | Manned lunar landing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operator | NASA[1] | ||||

| COSPAR ID |

| ||||

| SATCAT № |

| ||||

| Mission duration | 9 days, 1 minute, 58 seconds | ||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||

| Spacecraft |

| ||||

| Manufacturer |

CSM: North American Rockwell LM: Grumman | ||||

| Launch mass | 102,084 pounds (46,305 kg) | ||||

| Landing mass | 11,481 pounds (5,208 kg) | ||||

| Crew | |||||

| Crew size | 3 | ||||

| Members | |||||

| Callsign |

| ||||

| Start of mission | |||||

| Launch date | January 31, 1971, 21:03:02 UTC | ||||

| Rocket | Saturn V SA-509 | ||||

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A | ||||

| End of mission | |||||

| Recovered by | USS New Orleans | ||||

| Landing date | February 9, 1971, 21:05:00 UTC | ||||

| Landing site |

South Pacific Ocean 27°1′S 172°39′W / 27.017°S 172.650°W | ||||

| Orbital parameters | |||||

| Reference system | Selenocentric | ||||

| Periselene | 16.9 kilometers (9.1 nmi) | ||||

| Aposelene | 108.9 kilometers (58.8 nmi) | ||||

| Period | 120 minutes | ||||

| Lunar orbiter | |||||

| Spacecraft component | Command/Service Module | ||||

| Orbital insertion | February 4, 1971, 06:59:42 UTC | ||||

| Departed orbit | February 7, 1971, 01:39:04 UTC | ||||

| Orbits | 34 | ||||

| Lunar lander | |||||

| Spacecraft component | Lunar Module | ||||

| Landing date | February 5, 1971, 09:18:11 UTC | ||||

| Return launch | February 6, 1971, 18:48:42 UTC | ||||

| Landing site |

Fra Mauro 3°38′43″S 17°28′17″W / 3.64530°S 17.47136°W | ||||

| Sample mass | 42.80 kilograms (94.35 lb) | ||||

| Surface EVAs | 2 | ||||

| EVA duration |

| ||||

| Docking with LM | |||||

| Docking date | February 1, 1971, 01:57:58 UTC | ||||

| Undocking date | February 5, 1971, 04:50:43 UTC | ||||

| Docking with LM Ascent Stage | |||||

| Docking date | February 6, 1971, 20:35:52 UTC | ||||

| Undocking date | February 6, 1971, 22:48:00 UTC | ||||

Left to right: Roosa, Shepard, Mitchell

| |||||

Apollo 14 was the eighth manned mission in the United States Apollo program, and the third to land on the Moon. It was the last of the "H missions," targeted landings with two-day stays on the Moon with two lunar EVAs, or moonwalks.

Commander Alan Shepard, Command Module Pilot Stuart Roosa, and Lunar Module Pilot Edgar Mitchell launched on their nine-day mission on January 31, 1971 at 4:04:02 p.m. local time after a 40-minute, 2 second delay due to launch site weather restrictions, the first such delay in the Apollo program.[2] Shepard and Mitchell made their lunar landing on February 5 in the Fra Mauro formation - originally the target of the aborted Apollo 13 mission. During the two lunar EVAs, 42.80 kilograms (94.35 lb) of Moon rocks were collected,[3] and several scientific experiments were performed. Shepard hit two golf balls on the lunar surface with a makeshift club he had brought from Earth. Shepard and Mitchell spent 33½ hours on the Moon, with almost 9½ hours of EVA.

In the aftermath of Apollo 13, several modifications were made to the Service Module electrical power system to prevent a repeat of that accident, including redesign of the oxygen tanks and addition of a third tank.

While Shepard and Mitchell were on the surface, Roosa remained in lunar orbit aboard the Command/Service Module Kitty Hawk, performing scientific experiments and photographing the Moon, including the landing site of the future Apollo 16 mission. He took several hundred seeds on the mission, many of which were germinated on return, resulting in the so-called Moon trees. Shepard, Roosa, and Mitchell landed in the Pacific Ocean on February 9.

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Alan B. Shepard, Jr. Second and last spaceflight | |

| Command Module Pilot | Stuart A. Roosa Only spaceflight | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Edgar D. Mitchell Only spaceflight | |

Shepard was the oldest U.S. astronaut when he made his trip aboard Apollo 14.[4][5] He is the only astronaut from Project Mercury (the original Mercury Seven astronauts) to reach the Moon. Another of the original seven, Gordon Cooper, had (as Apollo 10's backup commander) tentatively been scheduled to command the mission, but according to author Andrew Chaikin, his casual attitude toward training, along with problems with NASA hierarchy (reaching all the way back to the Mercury-Atlas 9 flight), resulted in his removal.

The mission was a personal triumph for Shepard, who had battled back from Ménière's disease which grounded him from 1964 to 1968. He and his crew were originally scheduled to fly on Apollo 13, but in 1969 NASA officials switched the scheduled crews for Apollos 13 and 14. This was done to allow Shepard more time to train for his flight, as he had been grounded for four years.[6]

All three crew members are now dead, making Apollo 14 the first of the eleven successfully launched Apollo missions whose crew have all died: Roosa in 1994 from pancreatitis, Shepard in 1998 from leukemia, and Mitchell in 2016.

Backup crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Eugene A. Cernan | |

| Command Module Pilot | Ronald E. Evans, Jr. | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Joe H. Engle | |

| The backup crew (with Harrison Schmitt replacing Engle) would become the prime crew of Apollo 17. | ||

Support crew

Flight directors

- Pete Frank, Orange team

- Glynn Lunney, Black team

- Milton Windler, Maroon team

- Gerald D. Griffin, Gold team

Mission parameters

Geocentric:

- Mass: CSM 29,240 kg; LM 15,264 kg

- Perigee: 183.2 km

- Apogee: 188.9 km

- Orbital inclination: 31.12°

- Orbital period: 88.18 min

Selenocentric:

- Periselene: 108.2 km

- Aposelene: 314.1 km

- Orbital inclination: °

- Orbital period: 120 min

- Landing Site: 3.64530° S – 17.47136° W or

3° 38' 43.08" S – 17° 28' 16.90" W

LM – CSM docking

- Undocked: February 5, 1971 – 04:50:43 UTC

- Docked: February 6, 1971 – 20:35:42 UTC

EVAs

- EVA 1

- Start: February 5, 1971, 14:42:13 UTC

- Shepard – EVA 1

- Stepped onto Moon: 14:54 UTC

- LM ingress: 19:22 UTC

- Mitchell – EVA 1

- Stepped onto Moon: 14:58 UTC

- LM ingress: 19:18 UTC

- End: February 5, 19:30:50 UTC

- Duration: 4 hours, 47 minutes, 50 seconds

- EVA 2

- Start: February 6, 1971, 08:11:15 UTC

- Shepard – EVA 2

- Stepped onto Moon: 08:16 UTC

- LM ingress: 12:38 UTC

- Mitchell – EVA 2

- Stepped onto Moon: 08:23 UTC

- LM ingress: 12:28 UTC

- End: February 6, 12:45:56 UTC

- Duration: 4 hours, 34 minutes, 41 seconds

Mission highlights

Launch and flight to lunar orbit

Apollo 14 launched during heavy cloud cover and the Saturn V booster quickly disappeared from view. NASA's long-range cameras, based 60 miles south in Vero Beach, had a clear shot of the remainder of the launch. Following the launch, the Launch Control Center at Kennedy Space Center was visited by U.S. Vice President Spiro T. Agnew, Prince Juan Carlos of Spain, and his wife, Princess Sofía.

At the beginning of the mission, the CSM Kitty Hawk had difficulty achieving capture and docking with the LM Antares. Repeated attempts to dock went on for 1 hour and 42 minutes, until it was suggested that Roosa hold Kitty Hawk against Antares using its thrusters, then the docking probe would be retracted out of the way, hopefully triggering the docking latches. This attempt was successful, and no further docking problems were encountered during the mission.

Lunar descent

After separating from the Command Module in lunar orbit, the LM Antares also had two serious problems. First, the LM computer began getting an ABORT signal from a faulty switch. NASA believed that the computer might be getting erroneous readings like this if a tiny ball of solder had shaken loose and was floating between the switch and the contact, closing the circuit. The immediate solution — tapping on the panel next to the switch — did work briefly, but the circuit soon closed again. If the problem recurred after the descent engine fired, the computer would think the signal was real and would initiate an auto-abort, causing the ascent stage to separate from the descent stage and climb back into orbit. NASA and the software teams at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology scrambled to find a solution, and determined the fix would involve reprogramming the flight software to ignore the false signal. The software modifications were transmitted to the crew via voice communication, and Mitchell manually entered the changes (amounting to over 80 keystrokes on the LM computer pad) just in time.

A second problem occurred during the powered descent, when the LM landing radar failed to lock automatically onto the Moon's surface, depriving the navigation computer of vital information on the vehicle's altitude and vertical descent speed (this was not a result of the modifications to the ABORT command; rather, the post-mission report indicated it was an unrelated bug in the radar's operation). After the astronauts cycled the landing radar breaker, the unit successfully acquired a signal near 18,000 feet (5,500 m), again just in time. Shepard then manually landed the LM closer to its intended target than any of the other six Moon landing missions. Mitchell believed that Shepard would have continued with the landing attempt without the radar, using the LM inertial guidance system and visual cues. A post-flight review of the descent data showed the inertial system alone would have been inadequate, and the astronauts probably would have been forced to abort the landing as they approached the surface.

Lunar surface operations

Shepard and Mitchell named their landing site Fra Mauro Base, and this designation is recognized by the International Astronomical Union (depicted in Latin on lunar maps as Statio Fra Mauro).

Shepard's first words, after stepping onto the lunar surface were, "And it's been a long way, but we're here." Unlike Neil Armstrong on Apollo 11 and Pete Conrad on Apollo 12, Shepard had already stepped off the LM footpad and was a few yards (meters) away before he spoke.

Shepard's moonwalking suit was the first to utilize red stripes on the arms and legs and on the top of the lunar EVA sunshade "hood," so as to allow easy identification between the commander and LM pilot on the surface;[7] on the Apollo 12 pictures, it had been almost impossible to distinguish between the two crewmen, causing a great deal of confusion. This feature was included on Jim Lovell's Apollo 13 suit; because no landing was made on that mission, Apollo 14 was the first to make use of it. This feature was used for the remaining Apollo missions, and for the EVAs of Space Shuttle flights afterwards, and it is still in use today on both the U.S. and Russian space suits on the International Space Station.

After landing in the Fra Mauro formation—the destination for Apollo 13—Shepard and Mitchell took two moonwalks, adding new seismic studies[8] to the by now familiar Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), and using the Modular Equipment Transporter (MET), a pull-cart for carrying equipment and samples, nicknamed "lunar rickshaw". Roosa, meanwhile, took pictures from on board Command Module Kitty Hawk in lunar orbit.

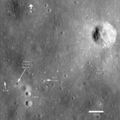

The second moonwalk, or EVA, was intended to reach the rim of the 1,000-foot (300 m) wide Cone Crater. The two astronauts were not able to find the rim amid the rolling terrain of the crater's slopes. They became physically exhausted from the attempt and with their suits' oxygen supplies starting to run low, the effort was called off. Later analysis, using the pictures that they took, determined that they had come within an estimated 65 feet (20 m) of the crater's rim. Images from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) show the tracks of the astronauts and the MET come to within 30 m of the rim.[9]

Shepard and Mitchell deployed and activated various scientific instruments and experiments and collected almost 100 pounds (45 kg) of lunar samples for return to Earth. Other Apollo 14 achievements included the only use of MET; longest distance traversed by foot on the lunar surface; first use of shortened lunar orbit rendezvous techniques; and the first extensive orbital science period conducted during CSM solo operations.

The astronauts also engaged in less serious activities on the Moon. Shepard brought along a six iron golf club head which he could attach to the handle of a lunar excavation tool, and two golf balls, and took several one-handed swings (due to the limited flexibility of the EVA suit). He exuberantly exclaimed that the second ball went "miles and miles and miles" in the low lunar gravity, but later estimated the distance as 200 to 400 yards (180 to 370 m). Mitchell then threw a lunar scoop handle as if it were a javelin.

Return, splashdown and quarantine

On the way back to Earth, the crew conducted the first U.S. materials processing experiments in space.

The Command Module Kitty Hawk splashed down in the South Pacific Ocean on February 9, 1971 at 21:05 [UTC], approximately 760 nautical miles (1,410 km) south of American Samoa. After recovery by the ship USS New Orleans, the crew was flown to Pago Pago International Airport in Tafuna for a reception before being flown on a C-141 cargo plane to Honolulu. The Apollo 14 astronauts were the last lunar explorers to be quarantined on their return from the Moon.

Roosa, who worked in forestry in his youth, took several hundred tree seeds on the flight. These were germinated after the return to Earth, and widely distributed around the world as commemorative Moon trees.[10]

Mission insignia

.jpg)

The oval insignia shows a gold NASA Astronaut Pin, given to U.S. astronauts upon completing their first space flight, traveling from the Earth to the Moon. A gold band around the edge includes the mission and astronaut names. The designer was Jean Beaulieu.

The backup crew spoofed the patch with its own version, with revised artwork showing a Wile E. Coyote cartoon character depicted as gray-bearded (for Shepard, who was 47 at the time of the mission and the oldest man on the Moon), pot-bellied (for Mitchell, who had a pudgy appearance) and red furred (for Roosa's red hair), still on the way to the Moon, while Road Runner (for the backup crew) is already on the Moon, holding a U.S. flag and a flag labeled "1st Team."[11] The flight name is replaced by "BEEP BEEP" and the backup crew's names are given. Several of these patches were hidden by the backup crew and found during the flight by the crew in notebooks and storage lockers in both the CSM Kitty Hawk and the LM Antares spacecraft, and one patch was even stored on the MET lunar hand cart.[12]

Spacecraft location

The Apollo 14 Command Module Kitty Hawk is on display at the Apollo/Saturn V Center building at the Kennedy Space Center after being on display at the United States Astronaut Hall of Fame near Titusville, Florida, for several years.

The ascent stage of Lunar Module Antares impacted the Moon on February 7, 1971 at 00:45:25.7 UT (February 6, 7:45 PM EST) 3°25′S 19°40′W / 3.42°S 19.67°W. Antares' descent stage and the mission's other equipment remain at Fra Mauro at 3°39′S 17°28′W / 3.65°S 17.47°W.

Photographs taken in 2009 by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter were released on July 17, and the Fra Mauro equipment was the most visible Apollo hardware at that time, owing to particularly good lighting conditions. In 2011, the LRO returned to the landing site at a lower altitude to take higher resolution photographs.[13]

Gallery

-

Apollo 14 astronaut Ed Mitchell sets foot on the Moon

-

Shepard and Mitchell erect a U.S. flag on the lunar surface

-

Reprocessed Lunar Orbiter 3 image taken in 1967, used in mission planning. The image is somewhat oblique and facing south at an illumination angle of about 34 degrees from the left (east).

-

Apollo 16 image showing the Apollo 14 landing site at the green dot near center. The hummocky terrain stretching from the lower left to the upper right is the approximate extent of the Fra Mauro formation.

-

Apollo 14 landing site, photograph by LRO

-

Later photo of landing site taken by LRO

See also

- Extravehicular activity

- Google Moon

- List of artificial objects on the Moon

- List of spacewalks and moonwalks 1965–1999

- Moon tree

- Splashdown

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ↑ Orloff, Richard W. (September 2004) [First published 2000]. "Table of Contents". Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 0-16-050631-X. LCCN 00061677. NASA SP-2000-4029. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ↑ Wheeler, Robin (2009). "Apollo lunar landing launch window: The controlling factors and constraints". Apollo Flight Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on April 2, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ↑ Orloff, Richard W. (September 2004) [First published 2000]. "Extravehicular Activity". Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. The NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 0-16-050631-X. LCCN 00061677. NASA SP-2000-4029. Retrieved August 1, 2013. For some reason, the total reported does not match the sum of the two EVAs.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (February 3, 2011). "Apollo 14 Moon shot: Alan Shepard 'told he was too old'". London: BBC News. Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- ↑ "1971 Year in Review: Apollo 14 and 15". UPI.com. United Press International. 1971. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ↑ Chaikin 2009

- ↑ von Braun, Wernher (July 1972). "Space Suits—from Pressurized Prison to Mini-Spacecraft". Popular Science: 121. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ↑ Brzostowski and Brzostowski, pp 414-416

- ↑ Lawrence, Samuel (August 19, 2009). "Trail of Discovery at Fra Mauro". Featured Images. Tempe, Arizona: LROC News System.

- ↑ Williams, David R. (28 July 2009). "The 'Moon Trees'". Goddard Space Flight Center. NASA. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ↑ Lotzmann, Ulrich; Jones, Eric M., eds. (2005). "Back-up-Crew Patch". Apollo 14 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Retrieved July 17, 2013. Image of backup crew patch.

- ↑ Jones, Eric M., ed. (1995). "Down the Ladder for EVA-1". Apollo 14 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ↑ Neal-Jones, Nancy; Zubritsky, Elizabeth; Cole, Steve (September 6, 2011). Garner, Robert, ed. "NASA Spacecraft Images Offer Sharper Views of Apollo Landing Sites". NASA. Goddard Release No. 11-058 (co-issued as NASA HQ Release No. 11-289). Retrieved July 17, 2013.

Bibliography

- Brzostowski, M.A., and Brzostowski, A.C., Archiving the Apollo active seismic data, The Leading Edge, Society of Exploration Geophysicists, April, 2009.

- Chaikin, Andrew (2009) [Originally published 1994]. A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. London: Michael Joseph. ISBN 978-0-14-104183-4. LCCN 93048680. OCLC 310154550.

- Lattimer, Dick (1985). All We Did Was Fly to the Moon. History-alive series. 1. Foreword by James A. Michener (1st ed.). Alachua, FL: Whispering Eagle Press. ISBN 0-9611228-0-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apollo 14. |

- "Apollo 14" at Encyclopedia Astronautica

- Apollo 14 Traverse Map at the Wayback Machine (archived September 19, 2006) – United States Geological Survey (USGS)

- "Apollo Mission Traverse Maps". USGS. Archived from the original on September 24, 2006. – Several maps showing routes of moonwalks

- Apollo 14 Science Experiments at the Lunar and Planetary Institute

NASA reports

- Apollo 14 Press Kit (PDF), NASA, Release No. 71-3K, January 21, 1971

- "Apollo Program Summary Report" (PDF), NASA, JSC-09423, April 1975

- The Apollo Spacecraft: A Chronology NASA, NASA SP-4009

- "Table 2-42. Apollo 14 Characteristics" from NASA Historical Data Book: Volume III: Programs and Projects 1969–1978 by Linda Neuman Ezell, NASA History Series (1988)

- "Masking the Abort Discrete" – by Paul Fjeld at the Apollo 14 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Detailed technical article describing the ABORT signal problem and its solution

- "Apollo 14 Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription" (PDF) Manned Spacecraft Center, NASA, February 1971

- NSSDC Master Catalog at NASA

Multimedia

- Apollo 14 "Mission to Fra Mauro" - NASA Space Program & Moon Landings Documentary on YouTube

- ""Apollo 14: Shepard, Roosa, Mitchell"". Archived from the original on 2011-05-04. Retrieved 2011-07-04. – slideshow by Life magazine

- "The Apollo Astronauts" – Interview with the Apollo 14 astronauts, March 31, 1971, from the Commonwealth Club of California Records at the Hoover Institution Archives

- "Apollo 14 Lunar Liftoff - Video" at Maniac World