Immigration Act of 1917

.svg.png) | |

| Other short titles | Asiatic Barred Zone Act |

|---|---|

| Legislative history | |

| |

The Immigration Act of 1917 (also known as the Literacy Act and less often as the Asiatic Barred Zone Act) was the most sweeping immigration act the United States had passed to date. It was the first bill aimed at restricting, as opposed to regulating, immigrants and marked a turn toward nativism. The law imposed literacy tests on immigrants, created new categories of inadmissible persons and barred immigration from the Asia-Pacific Zone. It governed immigration policy until amended by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 also known as the McCarran–Walter Act.

Background

Various groups, including the Immigration Restriction League had supported literacy as a prerequisite for immigration from its formation in 1894. In 1895, Henry Cabot Lodge had introduced a bill to the United States Senate to impose a mandate for literacy for immigrants, using a test requiring them to read five lines from the Constitution. Though the bill passed, it was vetoed by President Grover Cleveland in 1897. In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt lent support for the idea in his first address.[1] though the resulting proposal was defeated in 1903. Literacy was introduced again in 1912 and though it passed, it was vetoed by President William Howard Taft.[2] By 1915, yet another bill with a literacy requirement was passed. It was vetoed by President Woodrow Wilson because he felt that literacy tests denied equal opportunity to those who had not been educated.[1]

Previous immigration Acts, as early as 1882, had levied head taxes on aliens entering the country to offset the cost of their care if they became indigent, but excluded immigrants from Canada or Mexico,[3] as did subsequent amendments to the amount of the head tax.[4] The Immigration Act of 1882 prohibited entry to the U.S. for convicts, indigent people who could not provide for their own care, prostitutes, and lunatics or idiots.[5] The Alien Contract Labor Law of 1885 prohibited employers from contracting with foreign laborers and bringing them into the U.S.,[6] though U.S. employers continued to recruit Mexican contract laborers assuming they would just return home.[7] After the assassination of William McKinley, several immigration Acts were passed which broadened the defined categories of "undesireables". The Immigration Act of 1903 expanded barred categories to include anarchists, epileptics and those who had had episodes of insanity.[8] Those who had infectious diseases and those who had physical or mental disabilities which would hamper their ability to work were added to the list of excluded immigrants in the Immigration Act of 1907[9]

Anxiety over the fragmentation of American cultural identity, led to many laws aimed at stemming the Yellow Peril or perceived threat of Asian societies replacing the American identity with a foreign one.[10] Laws restricting Asian immigration to the United States had first appeared in California as state laws.[11] With the enactment of the Naturalization Act of 1870, which denied citizenship to Chinese immigrants and forbade all Chinese women,[12] exclusionary policies moved into the federal sphere. Exclusion of women aimed to cement a bachelor society, making Chinese men unable to form families and thus, transient, temporary immigrants.[13] Barred categories expanded with the Page Act of 1875, which established that Chinese, Japanese and Oriental bonded labor, convicts, and prostitutes were forbidden entry to the U.S.[14] The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred Chinese from entering the U.S. and the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 was made with Japan to regulate Japanese immigration to the US.[15]

Provisions

On February 5, 1917, the United States Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1917 with an overwhelming majority, overriding President Woodrow Wilson's December 14, 1916, veto.[2] This act added to and consolidated the list of undesirables banned from entering the country, including: "alcoholics", "anarchists", "contract laborers", "criminals and convicts", "epileptics", "feebleminded persons", "idiots", "illiterates", "imbeciles", "insane persons", "paupers", "persons afflicted with contagious disease", "persons being mentally or physically defective", "persons with constitutional psychopathic inferiority", "political radicals", "polygamists", "prostitutes" and "vagrants".[16]

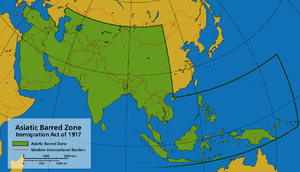

For the first time, an immigration law of the U.S. impacted European immigration with the provision barring all immigrants over the age of sixteen who were illiterate. Literacy was defined by being able to read 30-40 words of their own language from an ordinary text.[2] The Act reaffirmed the ban on contracted labor, but made a provision for temporary labor, which allowed laborers to obtain temporary permits, because they were inadmissible as immigrants. The waiver program, enabled continued recruitment of Mexican agricultural and railroad workers.[17] Legal interpretation on the terms "mentally defective" and "persons with constitutional psychopathic inferiority" effectively included a ban on homosexual immigrants who admitted their orientation.[18] One section of the law designated an "Asiatic Barred Zone", from which people could not immigrate, and included much of Asia and the Pacific Islands. The zone was described on longitudinal and latitudinal lines, excluding immigrants from Afghanistan, the Arabian Peninsula, Asiatic Russia, India, Malaysia, Myanmar, and the Polynesian Islands. Neither Japan nor the Philippines were included in the banned zone.[19] The law also increased the head tax to $8 per person and eliminated the exclusion of paying the head tax from Mexican workers.[4]

Aftermath

Almost immediately, the provisions of the law were challenged by Southwestern businesses. The advent of World War I, a few months after the law's passage, prompted a waiver of the Act's provisions on Mexican agricultural workers. It was soon extended to include Mexicans working in the mining and railroad industries and the exemptions continued through 1921.[4] The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943. The Luce-Celler Act of 1946 ended discrimination against Asian Indians and Filipinos, who were accorded the right to naturalization, and allowed a quota of 100 immigrants per year. The Immigration Act of 1917 was later altered formally by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, known as the McCarran-Walter Act. It extended the privilege of naturalization to Japanese, Koreans, and other Asians.[20] The McCarran-Walter Act revised all previous laws and regulations regarding immigration, naturalization, and nationality, and collected into one comprehensive statute.[21] Legislation barring homosexuals as immigrants remained part of the immigration code until passage of the Immigration Act of 1990.[22]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 Koven & Götzke 2010, p. 130.

- 1 2 3 Powell 2009, p. 137.

- ↑ Powell 2009, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 Coerver, Pasztor & Buffington 2004, p. 224.

- ↑ Powell 2009, pp. 135-136.

- ↑ Russell 2007, p. 48.

- ↑ Coerver, Pasztor & Buffington 2004, pp. 223-224.

- ↑ Powell 2009, pp. 136-137.

- ↑ History Central 2000.

- ↑ Railton 2013, p. 11.

- ↑ Chan 1991, p. 94-105.

- ↑ Soennichsen 2011, p. xiii.

- ↑ Pfaelzer 2008.

- ↑ Vong 2015.

- ↑ Van Nuys 2002, pp. 19, 72.

- ↑ Bromberg 2015.

- ↑ Chin & Villazor 2015, p. 294.

- ↑ Davis n.d.

- ↑ Sohi 2013, p. 534.

- ↑ “Commentary on Excerpt of the McCarran-Walter Act, 1952”, American Journal Online: The Immigrant Experience, Primary Source Microfilm, (1999), Reproduced in History Resource Center, Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, February 9, 2007

- ↑ "McCarran-Walter Act”, Dictionary of American History, 7 vols, Charles Scribner's Sons, (1976), Reproduced in History Resource Center, Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, February 9, 2007

- ↑ Chin & Villazor 2015, p. 250.

Bibliography

- Russell, John (2007). "Alien Contract Labor Law". In Arnesen, Eric. Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-class History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-96826-3.

- Bromberg, Howard (2015). "Immigration Act of 1917". Immigration to the United States. Archived from the original on November 22, 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Chan, Sucheng (1991). "4: The Exclusion of Chinese Women, 1870-1943". In Chan, Sucheng. Entry Denied: Exclusion and the Chinese Community in America, 1882-1943 (PDF). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-56639-201-3.

- Chin, Gabriel J.; Villazor, Rose Cuison (2015). The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: Legislating a New America. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08411-7.

- Coerver, Don M.; Pasztor, Suzanne B.; Buffington, Robert (2004). Mexico: An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Culture and History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-132-8.

- Davis, Tracy J. (n.d.). "Opening the Doors of Immigration: Sexual Orientation and Asylum in the United States". Washington, D.C.: Washington College of Law. Archived from the original on August 22, 2002. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Koven, Steven G.; Götzke, Frank (2010). American Immigration Policy: Confronting the Nation's Challenges. New York, New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-95940-5.

- Pfaelzer, Jean, ed. (2008). "Chinese American Women, A History of Resilience and Resistance: To Enter and Remain". NWHM. adviser: Weatherford, Doris; researchers: Chen, Shi; Hindmarch, Meghan and Love, Claire; designer: Emser, Nikki. Washington, D.C.: The National Women’s History Museum. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Powell, John (2009). Encyclopedia of North American Immigration. New York, New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1012-7.

- Railton, Ben (2013). The Chinese Exclusion Act: What It Can Teach Us about America. New York, New York: Pamgrave-McMillan. ISBN 978-1-137-33909-6.

- Soennichsen, John (2011). The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing/ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37947-5.

- Sohi, Seema (2013). "Immigration Act of 1917 and the "Barred Zone"". In Zhao, Xiaojian; Park, Edward J.W. Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 534–535. ISBN 978-1-59884-240-1.

- Van Nuys, Frank (2002). Americanizing the West: Race, Immigrants, and Citizenship, 1890-1930. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1206-8.

- Vong, Jimmy (2015). "1875 Page Law". University of Washington Bothell. Bothell, Washington: University of Washington-Bothell Library. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- "Immigration Act (1907)". History Central. New Rochelle, New York: MultiEductor. 2000. Archived from the original on February 28, 2001. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

External links

- The Text of the Act (PDF)

- UDayton.edu Timeline of Asian Pacific Americans and Immigration Law

- AILF.org Closed Borders and Mass Deportations: The Lessons of the Barred Zone Act

- PBS.org Text of the Act describing the limits of the Asiatic Barred Zone

- Helen F. Eckerson, "Immigration and National Origins"