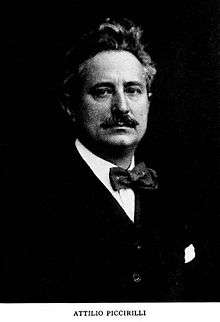

Attilio Piccirilli

Attilio Piccirilli (May 16, 1866 – October 8, 1945) was an American sculptor. Born in the province of Massa-Carrara, Italy, he was educated at the Accademia di San Luca of Rome.

Life and career

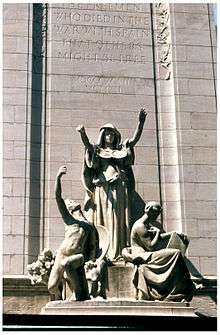

Piccirilli came to the United States in 1888 and worked for his father and then with the Piccirilli Brothers as a sculptor, modeler and stone carver at their studio in The Bronx, New York, at 467 East 142nd Street. This location is now a vacant lot. As artist in his own right, he is the author of the Maine Memorial in Columbus Circle, at the entrance to Central Park. One of the groups that he created for this monument was also used for his mother’s memorial in Woodlawn Cemetery. Also in New York he created a pediment and other sculptural details for the Frick Mansion on 5th Avenue and the Firemen's Memorial, a group of figures in Riverside Park.

As Piccirilli gained fame, he became invaluable to many American sculptors. Before Piccirilli and his family arrived in America, many American artists were forced to travel to Italy to have their models carved into stone. In the case of Attilio, if an artist presented him with small plaster model, Attilio could create a marble replica to any size. In fact, the vast majority of Attilio’s works were designed by other artists. Fragilina is one of the view works that was designed and sculpted into marble by Attilio himself. Piccirilli’s most famous work is the creation of the Lincoln statue for the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, which was originally designed by Daniel Chester French. Attilio and his family collaborated with Paul Eartlett, Frederick MacMonnies, Hermon MacNeil, Massey Rhind, Karl Bitter, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Olin Warner, Lorado Taft, Charles Niehaus, and Andrew O’Connor. Piccirrili also did architectural work for Cass Gilbert, Henry Bacon, McKim, Mead, and White, Carrére, and Hastings.[1] Attilio’s most famous works that which he designed and sculpted are the Maine Monument in Central Park, New York and the Fireman’s Monument on Riverside Drive, New York. He also designed a Monument to Guglielmo Marconi (1941) in Washington DC.

Piccirilli became a member of the National Academy of Design and the Architectural League. He won numerous prizes including a Gold Medal at the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. Attilio also helped create the Leonardo da Vinci Art School in New York City, New York. Its purpose was to give affordable training in art, like sculpture, to New York’s poor.

Piccirilli’s 1935 Pyrex glass relief sculpture Advance Forever, Eternal Youth over the entrance of the Palazzo d'Italia at Rockefeller Center was removed during World War Two when the Italian inscriptions were used by Mussolini,[2] and it was associated with fascist iconography. It disappeared from storage some years afterwards.

Piccirilli is represented in the sculpture collection at Brookgreen Gardens. His work is also found in museums around the United States. White marble "Fragilina" now stands in the newly re-arranged American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

He died in New York City in 1945. He is interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City. His half-length portrait by Edmond Thomas Quinn is in the collection of the National Academy of Design.[3]

Selected public commissions

- MacDonough Memorial, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1898

- Indian Literature and Indian Law Giver, facade of the Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York, 1909

- Maine Memorial, Columbus Circle, New York, 1913

- Firemen's Memorial, Riverside Drive, New York City. 1913[4]

- North pediment, Wisconsin State Capitol, Madison, Wisconsin. 1915

- Mothers' War Memorial, Albany, New York, 1923

- James Monroe Statue, Ash Lawn, Albemarle County, Virginia

- Thomas Jefferson Bust in Rotunda[5] of Virginia State Capitol, Capitol Square, Richmond, Virginia, 1931.

- James Monroe Bust in Rotunda of Virginia State Capitol, Capitol Square, Richmond, Virginia, 1931

- Advance Forever Eternal Youth (Sempre Avanti Eterna Giovinezza), The first of two glass sculptures, above Palazzo d'Italia entrance for Rockefeller Center, New York City, 1935, removed in 1940, destroyed 1968[6]

- Youth Leading Industry, The second of two glass (Pyrex) sculptures[7] (the first being 'Eternal Youth'), over the main entrance of the International Building 636 FIfth Avenue,[8] Rockefeller Center, New York City, 1935

- Present Day Postman, Post Office Building, Washington DC, 1936

- Joy of Life, frieze above doorway at One Rockefeller Plaza (48th Street Entrance),[9] New York City, 1937

- Guglielmo Marconi Memorial, Washington D.C. 1941

Fragilina

Fragilina is the name given to a sculpture completed by Attilio Piccirilli in 1923. The original is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, New York. It is 48 ½ inches by 15 ½ inches by 25 inches. It is completely made of marble. Piccirilli also made five additional smaller copies, one of which is in the Muscarelle Museum of Art at the College of William and Mary.[10]

“Fragilina” in Italian means “the little delicate one.” Fragilina is part of a series of female nudes that Attilio sculpted, beginning with “A Soul” in 1909. The woman in Fragilina is almost identical in pose to the woman in “A Soul.” Though, in Fragilina, more marble is cut away to leave a freer, fluid, and abstract work. Going with the theme of the work being abstract, many art critics the oval shaped head gives less definition of the hair and face. Some say, “the eyes appear almost veiled in stone.” When discussing Fragilina, Piccirilli said, “Every person has his own ideal of beauty stored away in his subconscious mind. When facial characteristics are precisely delineated, the observer is denied the opportunity of personally visualizing his ideal type. This reaction frequently takes place without full realization.” [11] So, as can be seen with Fragilina and his subsequent works, it can be said he was a minimalist. Piccirilli was described impeccably in the book, Attilio Piccirilli: Life of an American Sculptor, by Josef Vincent Lombardo. Lombardo writes, “Piccirilli’s art stands out boldly for its discipline, simplicity, and dignity.... His sculpture was and is simply tailored, free from adventitious detail and superficiality... Piccirilli’s style is distinctly personal and highly selective. Simplicity is his gospel, restraint his creed.” Fragilina was part of an exhibit at the National Sculpture Society in New York in 1923. It was also exhibited at the National Academy of Design commemorative exhibition in 1925. Piccirilli also made smaller versions of Fragilina, including two bronze casts. One of which is at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Notes

- ↑ Tolles, p.214.

- ↑ "ADVANCE FOREVER ETERNAL YOUTH by Attilio Piccirilli". artnet.com. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ It is illustrated in David Bernard Dearinger, Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design 2004:455.2004:455

- ↑ Another view of the sculptures.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-03-22. Retrieved 2014-05-02.

- ↑ Tolles, pg. 482

- ↑ http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F60617FE3B5B1B7B93C7A8178ED85F428385F9

- ↑ "Youth Leading Industry". rockefellercenter.com. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ http://www.rockefellercenter.com/art-and-history/art/the-joy-of-life/

- ↑ Forte, p.13.

- ↑ Gardner, p.95.

References

- Balfour, Alan, Rockefeller Center – Architecture As Theater, McGraw-Hill Book Company, NY, NY, 1978 Washington D.C. 1974

- Goode, James M. The Outdoor Sculpture of Washington D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press,

- Kvaran and Lockley Architectural Sculpture in America, unpublished manuscript

- Lombardo, Josef Vincent, Atilio Piccirilli: Life of an American Sculptor, Pitman Publishing Corporation, New York 1944

- National Sculpture Society, Contemporary American Sculpture 1929, National Sculpture Society, New York, NY 1929

- Opitz, Glenn B, Editor, Mantle Fielding’s Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors & Engravers, Apollo Book, Poughkeepsie NY, 1986

- Proske, Beatrice Gilman, Brookgreen Gardens Sculpture, Brookgreen Gardens, South Carolina, 1968

- Reynols, Donald Martin, "Masters of American Sculpture" Abbeville Press Publishers

- Crayen, Wayne, "Sculpture in America From the Colonial Period to the Present"

- Thayer Tolles (1999). American Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 2

- Albert Ten Eyck Gardner (1965). American Sculpture: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Kennis Forte (2011). Curators at Work: 16 Memoranda for the Curatorial Files