Baltic Way

|

| |

| Date | August 23, 1989 |

|---|---|

| Location | Estonian SSR, Latvian SSR, Lithuanian SSR |

| Also known as | Baltic Chain of Freedom |

| Participants | About 2 million people |

| Website |

balticway |

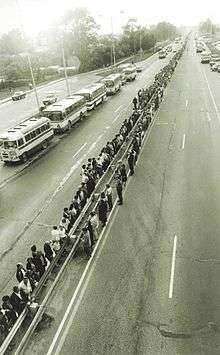

The Baltic Way or Baltic Chain (also Chain of Freedom,[1] Estonian: Balti kett, Latvian: Baltijas ceļš, Lithuanian: Baltijos kelias, Russian: Балтийский путь) was a peaceful political demonstration that occurred on 23 August 1989. Approximately two million people joined their hands to form a human chain spanning 675.5 kilometres (419.7 mi) across the three Baltic states – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, considered at the time to be constituent republics of the Soviet Union.

The demonstration originated in "Black Ribbon Day" protests held in the western cities in the 1980s. It marked the 50th anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. The pact and its secret protocols divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence and led to the occupation of the Baltic states in 1940. The event was organised by Baltic pro-independence movements: Rahvarinne of Estonia, the Tautas fronte of Latvia, and Sąjūdis of Lithuania. The protest was designed to draw global attention by demonstrating a popular desire for independence for each of the entities. It also illustrated solidarity among the three nations. It has been described as an effective publicity campaign, and an emotionally captivating and visually stunning scene.[2][3] The event presented an opportunity for the Baltic activists to publicise the illegal Soviet occupation and position the question of Baltic independence not as a political matter, but as a moral issue. The Soviet authorities in Moscow responded to the event with intense rhetoric,[2] but failed to take any constructive actions that could bridge the widening gap between the Baltic states and the Soviet Union. Within seven months of the protest, Lithuania became the first of the Soviet republics to declare independence.

After the Fall of Communism, 23 August has become an official remembrance day both in the Baltic countries, in the European Union and in other countries, known as the Black Ribbon Day or as the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism.

Background

Baltic stance

The Soviet Union denied the existence of the secret protocols to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, even though they were widely published by western scholars after surfacing during the Nuremberg Trials.[4] Soviet propaganda also maintained that there was no occupation and that all three Baltic states voluntarily joined the Union – the People's Parliaments expressed people's will when they petitioned the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union to be admitted into the Union.[5] The Baltic states claimed that they were forcefully and illegally incorporated into the Soviet Union. Popular opinion was that the secret protocols proved that the occupation was illegal.[6] Such an interpretation of the Pact had major implications in the Baltic public policy. If Baltic diplomats could link the Pact and the occupation, they could claim that the Soviet rule in the republics had no legal basis and therefore all Soviet laws were null and void since 1940.[7] Such a position would automatically terminate the debate over reforming Baltic sovereignty or establishing autonomy within the Soviet Union – the states never de jure belonged to the union in the first place.[8] This would open the possibility of restoring legal continuity of the independent states that existed in the interwar period. Claiming all Soviet laws had no legal power in the Baltics would also cancel the need to follow the Constitution of the Soviet Union and other formal secession procedures.[9]

In anticipation of the 50th anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, tensions were rising between the Baltics and Moscow. Lithuanian Romualdas Ozolas initiated a collection of 2 million signatures demanding withdrawal of the Red Army from Lithuania.[10] The Communist Party of Lithuania was deliberating the possibility of splitting off from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[11] On 8 August, 1989, Estonians attempted to amend election laws to limit voting rights of new immigrants (mostly Russian workers).[12] This provoked mass strikes and protests of Russian workers. Moscow gained an opportunity to present the events as an "inter-ethnic conflict"[13] – it could then position itself as "peacemaker" restoring order in a troubled republic.[14] The rising tensions in anticipation of the protest spurred hopes that Moscow would react by announcing constructive reforms to address the demands of the Baltic people.[15] At the same time fears grew of violent clampdown. Erich Honecker from East Germany and Nicolae Ceauşescu from Romania offered the Soviet Union military assistance in case it decided to use force and break up the demonstration.[16]

Soviet response

On 15 August, official daily Pravda, in response to worker strikes in Estonia, published sharp criticism of "hysteria" driven by "extremist elements" pursuing selfish "narrow nationalist positions" against the greater benefit of the entire Soviet Union.[12] On 17 August, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union published a project of new policy regarding the union republics in Pravda. However, this project offered few new ideas: it preserved Moscow's leadership not only in foreign policy and defense, but also in economy, science, and culture.[17] The project made few cautious concessions: it proposed the republics the right to challenge national laws in a court (at the time all three Baltic states had amended their constitutions giving their Supreme Soviets the right to veto national laws)[18] and the right to promote their national languages to the level of the official state language (at the same time the project emphasised the leading role of the Russian language).[17] The project also included law banning "nationalist and chauvinist organisations," which could be used to persecute pro-independence groups in the Baltics,[18] and a proposal to replace the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR of 1922 with a new unifying agreement, which would be part of the Soviet constitution.[17]

On 18 August, Pravda published an extensive interview with Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev,[19] chairman of a 26-member commission set up by the Congress of People's Deputies to investigate the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and its secret protocols.[4] During the interview, Yakovlev admitted that the secret protocols were genuine. He condemned the protocols, but maintained that they had no impact on the incorporation of the Baltic states.[20] Thus Moscow reversed its long-standing position that the secret protocols did not exist or were forgeries, but did not concede that events of 1940 constituted an occupation. It was clearly not enough to satisfy the Baltics and on 22 August, a commission of the Supreme Soviet of the Lithuanian SSR announced that the occupation in 1940 was a direct result of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and therefore illegal.[21] It was the first time that an official Soviet body challenged the legitimacy of the Soviet rule.[22][23]

Protest

Preparation

In the light of glasnost and perestroika, street demonstrations had been increasingly growing in popularity and support. On 23 August, 1986, Black Ribbon Day demonstrations were held in 21 western cities including New York, Ottawa, London, Stockholm, Seattle, Los Angeles, Perth, and Washington, DC to bring worldwide attention to human rights violations by the Soviet Union. In 1987, Black Ribbon Day protests were held in 36 cities including Vilnius, Lithuania. Protests against the Molotov Ribbentrop Pact were also held in Tallinn and Riga in 1987. In 1988, for the first time, such protests were sanctioned by the Soviet authorities and did not end in arrests.[7] The activists planned an especially large protest for the 50th anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in 1989. It is unclear when and by whom the idea of a human chain was advanced. It appears that the idea was proposed during a trilateral meeting in Pärnu on 15 July.[24] An official agreement between the Baltic activists was signed in Cēsis on 12 August.[25] Local Communist Party authorities approved the protest.[26] At the same time several different petitions, denouncing Soviet occupation, were gathering hundreds of thousands of signatures.[27]

The organisers mapped out the chain, designating specific locations to specific cities, towns, and villages to make sure that the chain would be uninterrupted. Free bus rides were provided for those who did not have other transportation.[28] Preparations spread across the country, energising the previously uninvolved rural population.[29] Some employers did not allow workers to take the day off from work (23 August fell on a Wednesday), while others sponsored the bus rides.[28] On the day of the event, special radio broadcasts helped to coordinate the effort.[26] Estonia declared a public holiday.[30]

The Baltic pro-independence movements issued a joint declaration to the world and European community in the name of the protest. The declaration condemned the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, calling it a criminal act, and urged declaration that the pact was "null and void from the moment of signing."[31] The declaration said that the question of the Baltics was a "problem of inalienable human rights" and accused the European community of "double standards" and turning a blind eye to the "last colonies of Hitler–Stalin era."[31] On the day of the protest, Pravda published an editorial titled "Only the Facts." It was a collection of quotes from pro-independence activists intended to show the unacceptable anti-Soviet nature of their work.[32]

Human chain

The chain connected the three Baltic capitals – Vilnius, Riga, and Tallinn. It ran from Vilnius along the A2 highway through Širvintos and Ukmergė to Panevėžys, then along the Via Baltica through Pasvalys to Bauska in Latvia and through Iecava and Ķekava to Riga (Bauska highway, Ziepniekkalna street, Mūkusalas street, Stone bridge, Kaļķu street, Brīvības's street) and then along road A2, through Vangaži, Sigulda, Līgatne, Mūrnieki and Drabeši, to Cēsis, from there, through Lode, to Valmiera and then through Jēči, Lizdēni, Rencēni, Oleri, Rūjiena and Ķoņi to Estonian town Karksi-Nuia and from there through Viljandi, Türi and Rapla to Tallinn.[33][34] The demonstrators peacefully linked hands for 15 minutes at 19:00 local time (16:00 GMT).[5] Later, a number of local gatherings and protests took place. In Vilnius, about 5,000 people gathered in the Cathedral Square, holding candles and singing national songs, including Tautiška giesmė.[35] Elsewhere, priests held masses or rang church bells. Leaders of the Estonian and Latvian Popular Fronts gathered on the border between their two republics for a symbolic funeral ceremony, in which a giant black cross was set alight.[30] The protesters held candles and pre-war national flags decorated with black ribbons in memory of the victims of the Soviet terror: Forest Brothers, deportees to Siberia, political prisoners, and other "enemies of the people."[23][35]

In Moscow's Pushkin Square, ranks of special riot police were employed when a few hundred people tried to stage a sympathy demonstration. TASS said 75 were detained for breaches of the peace, petty vandalism, and other offences.[35] About 13,000 demonstrated in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic which was also affected by the secret protocol.[36] A demonstration was held by the Baltic émigré and German sympathizers in front of the Soviet embassy in Bonn, then West Germany.

| Measure[37] | Estonia | Latvia | Lithuania |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population (1989) | 1.6M | 2.7M | 3.7M |

| Indigenous population (1959) | 75% | 62% | 79% |

| Indigenous population (1989) | 61% | 52%[38] | 80% |

Most estimates of the number of participants vary between one and two million. Reuters News reported the following day that about 700,000 Estonians and 1,000,000 Lithuanians joined the protests.[36] The Latvian Popular Front estimated an attendance of 400,000.[39] Prior to the event, the organisers expected an attendance of 1,500,000 out of the about 8,000,000 inhabitants of the three states.[35] Such expectations predicted 25–30% turnout among the native population.[29] According to the official Soviet numbers, provided by TASS, there were 300,000 participants in Estonia and nearly 500,000 in Lithuania.[35] To make the chain physically possible, an attendance of approximately 200,000 people was required in each state.[5] Video footage taken from airplanes and helicopters showed an almost continuous line of people across the countryside.[22]

Aftermath

"Matters have gone far. There is a serious threat to the fate of the Baltic peoples. People should know the abyss into which they are being pushed by their nationalistic leaders. Should they achieve their goals, the possible consequences could be catastrophic to these nations. A question could arise as to their very existence."

Declaration of the Central Committee on the situation in the Soviet Baltic republics, 26 August[40]

On 26 August, 1989, a pronouncement from the Central Committee of the Communist Party was read during the opening 19 minutes of Vremya, the main evening news program on Soviet television.[41] It was a sternly worded warning about growing "nationalist, extremist groups" which advanced "anti-socialist and anti-Soviet" agendas.[42] The announcement claimed that these groups discriminated against ethnic minorities and terrorised those still loyal to Soviet ideals.[42] Local authorities were openly criticised for their failure to stop these activists.[32] The Baltic Way was referred to as "nationalist hysteria." According to the pronouncement, such developments would lead to an "abyss" and "catastrophic" consequences.[27] The workers and peasants were called on to save the situation and defend Soviet ideals.[32] Overall, there were mixed messages: while indirectly threatening the use of force it also placed hopes that the conflict could be solved via diplomatic means. It was interpreted that the Central Committee had not yet decided which way to go and had left both possibilities open.[43] The call to pro-Soviet masses illustrated that Moscow believed it still had a significant audience in the Baltics.[32] Sharp criticism of Baltic Communist Parties was interpreted as signalling that Moscow would attempt to replace their leadership.[43]

President of the United States George H. W. Bush[44] and chancellor of West Germany Helmut Kohl urged peaceful reforms and criticised the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[45] On August 31, the Baltic activists issued a joint declaration to Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, Secretary-General of the United Nations.[46] They claimed to be under threat of aggression and asked for an international commission to be sent to monitor the situation. Almost immediately after the broadcast the tone in Moscow began to soften[47] and the Soviet authorities failed to follow up on any of their threats.[48] Eventually, according to historian Alfred Erich Senn, the pronouncement became a source of embarrassment.[48] On 19-20 September, the Central Committee of the Communist Party convened to discuss the nationality question – something Mikhail Gorbachev had been postponing since early 1988.[49] The plenum did not specifically address the situation in the Baltic states and reaffirmed old principles regarding the centralised Soviet Union and the dominant role of the Russian language.[50] It did promise some increase in autonomy, but was contradictory and failed to address the underlying reasons for the conflict.[51]

Evaluation

The human chain helped to publicise the Baltic cause around the world and symbolised solidarity among the Baltic peoples.[52] The positive image of the non-violent Singing Revolution spread among the western media.[53] The activists, including Vytautas Landsbergis, used the increased exposure to position the debate over Baltic independence as a moral, and not just political question: reclaiming independence would be restoration of historical justice and liquidation of Stalinism.[54][55] It was an emotional event, strengthening the determination to seek independence. The protest highlighted that the pro-independence movements, established just a year before, became more assertive and radical: they shifted from demanding greater freedom from Moscow to full independence.[22]

In December 1989, the Congress of People's Deputies accepted and Mikhail Gorbachev signed the report by Yakovlev's commission condemning the secret protocols of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[56] In February 1990, the first free democratic elections to the Supreme Soviets took place in all three Baltic states and pro-independence candidates won majorities. On 11 March, 1990, within seven months of the Baltic Way, Lithuania became the first Soviet state to declare independence. The independence of all three Baltic states was recognised by most western countries by the end of 1991.

This protest was one of the earliest and longest unbroken human chains in history. Similar human chains were later organised in many East European countries and regions of the USSR and, more recently, in Taiwan (228 Hand-in-Hand Rally) and Catalonia (Catalan Way). Documents recording the Baltic Way were added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in 2009 in recognition of their value in documenting history.[57][58]

See also

- Baltics are Waking Up

- Catalan Way

- Revolutions of 1989

- Singing Revolution

- 71st anniversary of Ukrainian unification

Notes

- ↑ Wolchik, Sharon L.; Jane Leftwich Curry (2007). Central and East European Politics: From Communism to Democracy. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 238. ISBN 0-7425-4068-5.

- 1 2 Dreifelds, Juris (1996). Latvia in Transition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-521-55537-X.

- ↑ Anušauskas (2005), p. 619

- 1 2 United Press International (12 August 1989). "Baltic Deal / Soviets Publish Secret Hitler Pact". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- 1 2 3 Conradi, Peter (18 August 1989). "Hundreds of Thousands to Demonstrate in Soviet Baltics". Reuters News.

- ↑ Senn (1995), p. 33

- 1 2 Dejevsky, Mary (23 August 1989). "Baltic Groups Plan Mass Protest; Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia's Struggle for Independence". The Times.

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), p. 336

- ↑ Senn (1995), p. 91

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), pp. 317, 326

- ↑ Conradi, Peter (16 August 1989). "Lithuania's Communist Party Considers Split from Moscow". Reuters News.

- 1 2 Fisher, Matthew (16 August 1989). "Moscow Condemns 'Hysteria' in Baltics". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ Blitz, James (16 August 1989). "Moscow Voices Growing Concern Over Ethnic Conflict". Financial Times. p. 2.

- ↑ Senn (1995), p. 30

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), p. 330

- ↑ Ashbourne, Alexandra (1999). Lithuania: The Rebirth of a Nation, 1991–1994. Lexington Books. p. 24. ISBN 0-7391-0027-0.

- 1 2 3 Laurinavičius (2008), p. 334

- 1 2 "Soviet party leaders accept Baltic demand". Houston Chronicle. Associated Press. 17 August 1989.

- ↑ Vardys, Vytas Stanley; Judith B. Sedaitis (1997). Lithuania: The Rebel Nation. Westview Series on the Post-Soviet Republics. Westview Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 0-8133-1839-4.

- ↑ Remnick, David (19 August 1989). "Kremlin Acknowledges Secret Pact on Baltics; Soviets Deny Republics Annexed Illegally". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Senn (1995), p. 66

- 1 2 3 Fein, Esther B. (24 August 1989). "Baltic Citizens Link Hands to Demand Independence". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Dobbs, Michael (24 August 1989). "Huge Protest 50 Years After Soviet Seizure". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Anušauskas (2005), p. 617

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), p. 326. Full text

- 1 2 Dobbs, Michael (24 August 1989). "Baltic States Link in Protest 'So Our Children Can Be Free'; 'Chain' Participants Decry Soviet Takeover". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 Imse, Ann (27 August 1989). "Baltic Residents Make Bold New Push For Independence". Associated Press.

- 1 2 Alanen (2004), p. 100

- 1 2 Alanen (2004), p. 78

- 1 2 Lodge, Robin (23 August 1989). "More than Two Million Join Human Chain in Soviet Baltics". Reuters News.

- 1 2 "The Baltic Way" (PDF). Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian National Commissions for UNESCO. 17 August 1989.

- 1 2 3 4 Senn (1995), p. 67

- ↑ http://www.ltfmuz.lv/files/Iepirkums_tfm_m-ksliniecisk-_risin-juma_realiz-cija2.doc

- ↑ "The Baltic Way". Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Imse, Ann (23 August 1989). "Baltic Residents Form Human Chain in Defiance of Soviet Rule". Associated Press.

- 1 2 Lodge, Robin (23 August 1989). "Human Chain Spanning: Soviet Baltics Shows Nationalist Feeling". Reuters News.

- ↑ Dobbs, Michael (27 August 1989). "Independence Fever Sets Up Confrontation". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia". csb.lv. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "Pravda chides Baltic activists". Tulsa World. Associated Press. 24 August 1989.

- ↑ Misiunas, Romuald J.; Rein Taagepera (1993). The Baltic States: Years of Dependence 1940–1990 (expanded ed.). University of California Press. p. 328. ISBN 0-520-08228-1.

- ↑ Fein, Esther B. (27 August 1989). "Moscow Condemns nationalist 'Virus' in 3 Baltic Lands". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Remnick, David (27 August 1989). "Kremlin Condemns Baltic Nationalists; Soviets Warn Separatism Risks 'Disaster'". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 Laurinavičius (2008), p. 347

- ↑ Hines, Cragg (29 August 1989). "Bush Urges Restraint in Baltics Dealings". Houston Chronicle.

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), pp. 351–352

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), p. 352

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), p. 350

- 1 2 Senn (1995), p. 69

- ↑ Senn (1995), p. 70

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), p. 361

- ↑ Winfrey, Paul (25 September 1989). "Flaws in Soviet Plan to End Strife: Moscow's Attempt to Cope with Nationalist Turmoil". Financial Times.

- ↑ Taagepera, Rein (1993). Estonia: Return to Independence. Westview Series on the Post-Soviet Republics. Westview Press. p. 157. ISBN 0-8133-1703-7.

- ↑ Plakans, Andrejs (1995). The Latvians: A Short History. Studies of Nationalities. Hoover Press. p. 174. ISBN 0-8179-9302-9.

- ↑ Katell, Andrew (22 August 1989). "Baltics Call Soviet Annexation a 'Crime,' Equate Hitler, Stalin". Associated Press.

- ↑ Senn (1995), p. 155

- ↑ Senn (1995), p. 78

- ↑ "Thirty-Five Documentary Properties Added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register". ArtDaily.org. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- ↑ "The Baltic Way – Human Chain Linking Three States in Their Drive for Freedom". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2009-07-31. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

References

- Alanen, Ilkka (2004). Mapping the Rural Problem in the Baltic Countryside: Transition Processes in the Rural Areas of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Perspectives on Rural Policy and Planning. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-3434-5.

- Anušauskas, Arvydas; et al., eds. (2005). Lietuva, 1940–1990 (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras. ISBN 9986-757-65-7.

- Laurinavičius, Česlovas; Vladas Sirutavičius (2008). Sąjūdis: nuo "persitvarkymo" iki kovo 11-osios. Part I. Lietuvos istorija (in Lithuanian). XII. Baltos lankos, Lithuanian Institute of History. ISBN 978-9955-23-164-6.

- Senn, Alfred Erich (1995). Gorbachev's Failure in Lithuania. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-12457-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baltic Way. |

- Full-text of joint Baltic declaration to the world

- Footage of the Baltic Way with soundtrack of the trilingual Baltic independence song Baltics are Waking Up

- Footage of the Baltic Way with soundtrack of the Lithuanian independence song Pabudome ir kelkimės

- Documentary Baltijos kelias by the Lithuanian Television

- Photo album, a virtual gallery hosted by the Government of Lithuania

- Stamps of the Baltic States Mail Offices, commemorating the Baltic Way