Battle of Longewala

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Longewala (4–7 December 1971) was one of the first major engagements in the Western Sector during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, fought between assaulting Pakistani forces and Indian defenders at the Indian border post of Longewala, in the Thar Desert of the Rajasthan state in India.

The "A" company (reinforced) of the 23rd Battalion, Punjab Regiment,[9] under the Indian Army's 30th Infantry, commanded by Major Kuldip Singh Chandpuri, was left with the choice of either attempting to hold out until reinforced, or fleeing on foot from a mechanised infantry Pakistani force. Choosing the former, Major Kuldip Singh Chandpuri ensured that all his assets were correctly deployed, and made the most use of his strong defensive position, and weaknesses created by errors in enemy tactics. He was also fortunate in that an Indian Air Force forward air controller was able to secure and direct aircraft in support of the post's defence until reinforcements arrived six hours later.

The Pakistani commanders made several questionable decisions, including a failure of their strategic intelligence to foresee availability of Indian strike aircraft in the Longewala area, exercising operational mobility with little or no route reconnaissance, and conducting a tactical frontal assault with no engineer reconnaissance. This led to the Pakistani brigade group being left extremely vulnerable to air attack, vehicles becoming bogged in terrain not suitable for the movement of armoured vehicles as they tried to deploy off a single track, these being more susceptible to enemy fire by using external fuel storage in tactical combat, attempting to execute a night attack over unfamiliar terrain, and infantry being surprised by obstacles to troop movement causing confusion and stalling the attack during the crucial hours of darkness, when the assaulting infantry still had a measure of concealment from Indian small arms and infantry support weapon fire.

Background

The main thrust of the Indian Army during the 1971 war was directed towards the eastern theatre, with the western sector envisaged as a holding operation to prevent the Pakistan Army from achieving any success that would allow the President of Pakistan, Yahya Khan, any bargaining tool to trade against the captured territories in the east. By the last week of November 1971, the Indian Army had launched offensive manoeuvres at Atgram against Pakistani border posts and communications centres along the eastern border. The Mukti Bahini also launched an offensive on Jessore at this time.[10] It was clear to Islamabad by this time that open conflict was inevitable, and that East Pakistan was indefensible in the long run.[11] Yahya Khan chose at this point to try to protect Pakistan's integrity and to hold India by Ayub Khan's strategy – "The defence of East Pakistan lies in the West".[12]

Prelude

The Western sector

Khan's policy made the assumption that an open conflict with India would not last long due to International pressure, and that since East Pakistan was undefendable, the war-effort should be concentrated on occupying as large an area of Indian territory as possible as a bargaining tool at the negotiating table. To this end, Gen Tikka Khan had proposed an offensive into India, and the PAF's "overriding priority was to give maximum support to this offensive". The initial plans for the offensive called for at least a temporary cover of air dominance by the PAF under which Khan's troops could conduct a lightning campaign deep into Western India before digging in and consolidating their positions. To support Khan's troops, the PAF had launched pre-emptive strikes on the evening of 3 December that led to the formal commencement of hostilities. In the western theatre, the town of Rahim Yar Khan, close to the international border, formed a critical communication centre for Khan's forces and, situated on the Sindh — Punjab railway, remained a vulnerable link on Khan's logistics. The fall of Rahim Yar Khan to Indian forces would cut off the rail as well as road link between Sindh and Punjab, starving Khan's forces of fuel and ammunitions delivered to Karachi.

Indian battle plans called for a strike across the international border with the 12th Indian division towards Islamgarh through Sarkari Tala, subsequently advancing through Baghla to secure Rahim Yar Khan, which would not only destabilise the Pakistani defences in the Punjab, but also in the Jammu & Kashmir Sector, allowing the planned Indian offensive in the Shakargarh sector to sweep the Pakistani forces trapped there.[13]

Pakistan, which envisaged the Punjab as an operational centre, had a strong intelligence network in the area and planned to counter its own comparatively weak strength on the ground with a pre-emptive strike through Kishangarh towards the divisional headquarters south of Ramgarh[13] Pakistani intelligence was able to infiltrate the operations area posing as local people and passing on information. However, these sources failed to pass on information on the Longewala post which, originally a BSF post, was now held by a company of the Punjab Regiment. Longewala formed a strategic point en route to capturing vast tracts of land and also a pivotal theatre of war in engaging India on the western front.

Tactical plan

Pakistan's tactical plan was based on the assumption that an attack in the area would help Pakistan’s 1st Armoured Divisions task in the Sri Ganganagar area. Pakistan High command also felt that it was important to protect the North-South road link which they felt was vulnerable as it was close to the border. A Combined Arms Plan was decided upon. This involved two Infantry Brigades and two Armoured Regiments. A separate division, the 18 Division, was formed for this purpose. 18 Division Operation Orders required one Infantry Brigade (206) with an Armoured Regiment (38 Cavalry) to capture and establish a firm base at Longewala, a junction on the Indian road system and 51st Infantry Brigade and the 22nd Cavalry (Pakistan Army Armoured Corps) to operate beyond Longewala to capture Jaisalmer.[14]

The Pakistani plan was to reach Longewala, Ramgarh and Jaisalmer". The plan was far-fetched from the start, if only because it called for a night attack to be conducted over terrain that was not preceded by route or engineer reconnaissance, and the armoured troops were therefore unaware of the ground surface that could not support rapid movement towards the objective. As the day unfolded, Longewala would stand out as one of the biggest losses in a battle for Pakistan despite overwhelming superiority before commencement of the battle, largely due to the vehicles becoming bogged down in soft sand.

Indian defensive planning

On the Indian side, the post was held by the A company of the 23rd Battalion, Punjab Regiment,[9] led by Major K S Chandpuri, the defences occupying a high sand dune which dominated the area that was largely intractable to vehicles. The post was surrounded by a barbed wire fence of three stands. The rest of the battalion was located at Sadhewala, 17 km north-east of the Longewala post. Chandpuri commanded an infantry company reinforced by a section each of MMGs and L16 81mm Mortar, and one Jeep-mounted RCL. His two other recoilless rifle teams of the anti-tank section were under training at the battalion headquarters. Major Chandpuri also had under his command a four-man team of the camel Border Security Force division.[15] The Longewala post had no armoured vehicles, but artillery support was available from a battery of 170 Field Regiment (Veer Rajput) tasked in direct support to the battalion, and 168 Field Regiment which had been deployed to the area in secrecy just a day earlier. The direct support battery was attached to the 168 Field Regiment and served as its "Sierra" Battery. Immediately after PAF strikes on Indian airfields on 3 December, Chandpuri dispatched a 20-man strong patrol under Lieutenant Dharam Veer to Boundary Pillar (BP) 638, on the international border. This patrol was to play an important part in detecting the advances of Pakistani forces.

Battle

During the night of the 4th, Lt. Veer's platoon conducting a patrol detected noises across the border that suggested a large number of armoured vehicles approaching.[16] These were soon confirmed by reports — from the Army's Air Observation Post aircraft flown by Maj. Atma Singh — in the area of a 20 km long armoured column on the track leading to the post advancing in the general direction of the Longewala post.[17] Directing Lt Veer's patrol to trail the advancing armoured column, Chandpuri got in touch with the battalion headquarters requesting urgent reinforcements and armour and artillery support. Battalion HQ gave him the choice of staying put, and containing the attack as much as possible, or carrying out a tactical retreat of the company to Ramgarh, as reinforcements would not be available for at least six hours. Considering that Chandpuri's command had no transportation, and was facing a mobile enemy, he decided to maintain the defensive position of the post where his troops at least had the benefit of prepared defensive works, rather than conducting a withdrawal at night that was a far riskier option.

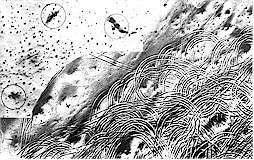

The Pakistani forces began their attack at 12:30 am.[18] As the offensive approached the lone outpost, Pakistani artillery opened up across the border with medium artillery guns, killing five of the ten camels from the BSF detachment. As the column of 45 tanks neared the post, Indian defences, lacking the time to lay a prepared minefield, laid a hasty anti-tank minefield as the enemy advanced, one infantryman being killed in the process.[19] The Indian infantry held fire until the leading Pakistani tanks had approached to 15–30 metres before firing their PIATs.[19] They accounted for the first two tanks on the track with their Jeep-mounted 106 mm M40 recoilless rifle,[20] with one of its crew being killed during the combat. This weapon proved quite effective because it was able to engage the thinner top armour of the Pakistani tanks from its elevated position, firing at often stationary bogged down vehicles. In all the post defenders claimed 12 tanks destroyed or damaged. The initial Pakistani attack stalled almost immediately when the infantry discovered the barbed wire which was unseen in the night, and interpreted it to signify a minefield. Firing for the Indian RCL crews was made easier by the flames of fires when the spare fuel tanks on the Pakistani tanks, intended to supplement their internal capacity for the advance to Jaisalmer, exploded, at once providing ample light for Indians located on higher ground, and creating a dense acrid smoke screen at ground level for the Pakistani infantry, adding to the confusion. Two hours were lost as Pakistani sappers were brought up, only to discover there was no minefield. However, at this time Pakistani infantry were required to make another attack, from a different direction, but in the dawn light. The Pakistani advance then attempted to surround the post two hours later by vehicles getting off the road, but many vehicles, particularly armoured personnel carriers and tanks, in trying to soften up the Indian defenders before attacking, became bogged in the soft sand of the area surrounding the post. Throughout the engagement Major Chandpuri continued to direct the supporting artillery fire.[19]

Although massively outnumbering the Indian defenders, and having surrounded them, the Pakistani troops were unable to advance over open terrain on a full-moon night,[18] under small arms and mortar fire from the outpost. This encouraged the Indians not to give up their strong defensive position, frustrating the Pakistani commanders. As dawn arrived, the Pakistan forces had still not taken the post, and were now having to do so in full daylight.

In the morning the Indian Air Force was finally able to direct some HF-24 Maruts and Hawker Hunter aircraft to assist the post; they were not outfitted with night vision equipment, and so were delayed from conducting combat missions until dawn.[21] With daylight, however, the IAF was able to operate effectively, with the strike aircraft being guided to the targets by the airborne Forward Air Controller (FAC) Major Atma Singh in a HAL Krishak.[22] The Indian aircraft attacked the Pakistani ground troops with the 16 Matra T-10 rockets and 30 mm cannon fire on each aircraft. Without support from the Pakistan Air Force, which was busy elsewhere, the tanks and other armoured vehicles were easy targets for the IAF's Hunters. The range of the 12.7 mm anti-aircraft heavy machine guns mounted on the tanks was limited and therefore ineffective against the Indian jets. Indian air attacks were made easier by the nature of the barren terrain. Many IAF officers later described the attack as a 'Turkey Shoot' signifying the lopsidedness. By noon the next day, the assault ended completely, having cost Pakistan 22 tanks claimed destroyed by aircraft fire, 12 by ground anti-tank fire, and some captured after being abandoned, with a total of 100 vehicles claimed to have been destroyed or damaged in the desert around the post. The Pakistani attack was first halted, and then Pakistani forces were forced to withdraw when Indian tanks from division's cavalry regiment the 20 Lancers, Commanded by Col Bawa Guruvachan Singh, and the 17th Rajputana Rifles launched their counter-offensive to end the six-hour combat;[19] Longewala had proved to be one of the defining moments in the war.

Aftermath

The battle of Longewala saw heavy Pakistani losses and low Indian casualties. Since the Indians were able to use the defenders' advantage, they managed to inflict heavy losses on the Pakistanis. Indian casualties in the battle were two soldiers along with one of their jeep mounted recoil-less rifles knocked out. Pakistani losses were 200 soldiers killed.[8] The Pakistanis also suffered the loss of 34 tanks destroyed or abandoned, and lost 500 additional vehicles.[7] The judicial commission set up at the end of war recommended the commander of 18 division Major General Mustafa to be tried for negligence during the war.[23]

Notwithstanding the Indian victory, there were intelligence and strategic failures on both sides. India's intelligence failed to provide warning of such a large armoured force in the western sector. Moreover, the defending post was not heavily armed to neutralise the enemy. Finally, they did not push home the advantage by destroying the fleeing Pakistani tanks, while the IAF had them on the run. They did, however destroy or capture some 36 tanks,[24] remaining one of the largest disproportionate tank casualties for one side in a single battle after World War II.

Invading Pakistan troops meanwhile, had overestimated the Longewala post's defensive capability due to the difficulty of approach over sand, conducting the attack at night and in full-moon light, against stiff resistance encountered there from a well prepared defensive position located on a dominant height. Attacking with virtually no air cover, they took too long to close for an assault on the position, and failed to anticipate availability of Indian close air support. Given that Pakistan's Sherman tanks and T-59/Type 59 Chinese tanks were slow on the sandy Thar desert, some military analysts[25] have opined that the attack may have been a poorly planned and executed given the terrain. Some Pakistan tanks had suffered engine failures due to overheating in trying to extricate themselves, and were abandoned. The open desert battleground provided little to no cover for the tanks and infantry from air attacks. The plan to capture Longewala may have been good in conception, but failed due to lack of air cover. As a result, two tank regiments failed to take Longewala.

For his part, the Indian company commander Major (later Brigadier) Kuldip Singh Chandpuri was decorated with India's second highest gallantry award, the Maha Vir Chakra. Several other awards were earned by members of the defending company, and the battalion's commander. On the other hand, the Pakistani divisional commander was dismissed from service. However, the commander of the Pakistani 51 Brigade who mounted the daring attack and crossed into Indian territory was later awarded Pakistan's high award of the Sitara-e-Imtiaz.

The British media significantly exploited the defence of Longewala. James Hatter compared the Battle of Longewala as to Battle of Thermopylae in his article Taking on the enemy at Longewala describing it as the deciding moment of the 1971 war.[24] Similarly, Field Marshal R.M. Carver, the British Chief of the Imperial General Staff, visited Longewala a few weeks after the war to learn the details of the battle from Major Chandpuri.[24]

In the early twenty-first century the battle was the subject of disagreement, some officers of the time ascribing all the combat success to the air-force.[26][27][28] The Kuldip Singh Chandpuri sued for a nominal one Rupee damages.

In popular culture

The Battle of Longewala was depicted in the 1997 Bollywood Hindi film Border, which was directed by J.P. Dutta and starred Sunny Deol as the Major Kuldip Singh Chandpuri, Jackie Shroff as the Wing Commander M.S. Bawa, Sunil Shetty as the Rajput Border Security Force Captain Bhairon Singh, and then the teen idol Akshaye Khanna as Lt. Dharam Veer Bhan.[29] The main criticism of the movie was that it showed Indian forces being in a terrible position before any sort of help came from the Indian Air Force. The movie also exaggerates the casualties of Indian soldiers for dramatic purposes.[30] This was not the case in the real incident as Indian forces had defended a position on a height that commanded the area, and were able to defend it effectively due to tactical mistakes made by the Pakistani commanders. This resulted in only two jawan casualties before combat ceased. Indian troops were later able to capture damaged or abandoned Pakistani tanks.[31]

External links

- Longewal Battle short summary

- Longewal Battle documentary, part-1

- Longewal Battle documentary, part-2

- Battle of Longewal

- The battle from the Indian Air Force Journal, 1997

- The Western Theatre in 1971;— A Strategic and Operational Analysis by A.H. Amin - Orbat

See also

Citations and notes

- ↑ p.1187, IDSA

- ↑ Lal, Pratap Chandra. My Years With The Iaf. ISBN 978-81-7062-008-2. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Karl R. DeRouen; Uk Heo (2007). Civil Wars of the World: Major Conflicts Since World War II. ABC-CLIO. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-1-85109-919-1.

- ↑ Singh, Polly. "HAL HF-24 Marut - Where the wind blows". bharat-rakshak.com. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "HAL HF 24 Marut India's First Indigenous Fighter Aircraft - Battle of longewala". vidinfo.org. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ DeRouen, Karl R. (2007). Karl R. DeRouen, Uk Heo, ed. Civil Wars of the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 596. ISBN 978-1851099191.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-First Century. Greenwood. p. 597. ISBN 978-0313335389.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Col J Francis (Retd) (30 August 2013). Short Stories from the History of the Indian Army Since August 1947. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. pp. 93–96. ISBN 978-93-82652-17-5.

- 1 2 "The Tribune - Windows - Featured story". tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "Pakistan — Yahya Khan and Bangladesh". Library of Congress Country Studies. April 1994. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ↑ Kyle, R.G. (14 March 1964). "The India-Pakistan War Of 1971: A Modern War". Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ↑ Failure in Command: Lessons from Pakistan's Indian Wars, 1947–1999. Faruqui A. Defense Analysis Vol.17, No. 1, 1 April 2001

- 1 2 Thakur Ludra, K. S. (13 January 2001). "An assessment of the battle of Longewala". India: The Tribune. p. 1. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ↑ Correspondence from Lt. Col. (Retd) H.K. Afridi Defence Journal,Karachi. feb-mar99 Archived 22 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine. URL accessed on 22 September 2006

- ↑ Shorey A. Sainik Samachar. Vol.52, No.4, 16–28 February 2005

- ↑ p.177, Nayar

- ↑ p.239, Rao

- 1 2 p.83, Imprint

- 1 2 3 4 p.42, Sharma

- ↑ there is a suggestion there were two RCL-armed Jeeps at the post

- ↑ p.100, Nordeen

- ↑ An IAF pilot's account of the battle Archived 5 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine., Suresh

- ↑ Hamoodur Rehman; Sheikh Anwarul Haq; Tufail Ali Abdul Rehman. Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report (PDF) (Report). Government of Pakistan. p. 79-80. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Hattar, James (16 December 2000). "Taking on the enemy at Longewala". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ↑ "Pakistan Army Order of Battle — Corps Sectors". Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ "The truth of courage". tehelka."The truth of courage". tehelka.

- ↑ "Army lied to the nation Longewala?". Hindustan times. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014.

- ↑ Sura, Ajay (29 November 2013). "War veteran's book reiterates doubts over Army's role in Longewala battle". Times of India.

- ↑ p.17, Alter

- ↑ "Border". 1 January 2000. Retrieved 2 August 2016 – via IMDb.

- ↑ p.17-18, Alter

References

- Indivisible Air Power, Strategic Analysis, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, 1984, v.8, 1185–1202

- Imprint, Justified Press, 1972, v.12:7-12 (Oct 1972-Mar 11973)

- Alter, Stephen, Amritsar to Lahore: A Journey Across the India-Pakistan Border, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000

- Nordeen, Lon O., Air Warfare in the Missile Age, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985

- Suresh, Kukke, Wg. Cdr. (Retd), Battle of Longewala: 5 and 6 December 1971, 1971 India Pakistan Operations, http://www.bharat-rakshak.com

- Sharma, Gautam, Valour and Sacrifice: Famous Regiments of the Indian Army, Allied Publishers, 1990

- Nayar, Kuldip, Distant Neighbours: A Tale of the Subcontinent, Vikas Publishing House, 1972

- Rao, K. V. Krishna, Prepare Or Perish: A Study of National Security, Lancers Publishers, 1991

Further reading

- Anil Shorey Pakistan's Failed Gamble: The Battle of Laungewala Manas, 2005, ISBN 81-7049-224-6.

- Brigadier Zafar Alam Khan The Way It Was. He was probably the commanding officer of the 22nd Armoured Regiment.

- Virendra Verma, Hunting hunters: Battle of Longewala, December 1971: a study in joint army-air operations (Stories of war in post-independence India), Youth Education Publications, 1992