Battle of Gallabat

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

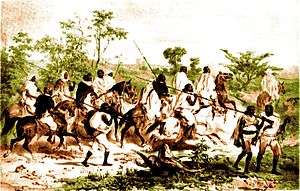

The Battle of Gallabat (also called the Battle of Metemma) was fought 9–10 March 1889 between the Mahdist Sudanese and Ethiopian forces. It is a critical event in Ethiopian history because Nəgusä Nägäst (or Emperor) Yohannes IV was killed in this battle. The fighting occurred at the site of the twin settlements of Gallabat (in modern Sudan) and Metemma (in modern Ethiopia), so both names are commonly used and either can be argued to be correct.

Background

When the Mahdists rebelled against the Egyptians, many Egyptian garrisons found themselves isolated in Sudan. As a result, the British, who had taken over the government of Egypt, negotiated the Treaty of Adowa with Emperor Yohannes IV of Ethiopia on 3 June 1884 whereby the Egyptian garrisons were allowed to evacuate to Massawa through Ethiopian territory. After that, the Mahdist Khalifa, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, considered the Ethiopians as his enemies and sent his forces to attack them.

The twin communities of Gallabat and Metemma were located on the trade route from the Nile to Gondar, the old Imperial capital; the Mahdists used these communities as their base for attacks on Ethiopia. These raids led to a Mahdist defeat by Ras Alula on 23 September 1885 at Kufit.

Sack of Gondar

A few years later, the negus of Gojjam, Tekle Haymanot (a vassal of Emperor Yohannes) attacked the Mahdists at Metemma in January 1887, and sacked the town. In response, that next year the Mahdists under Abu Anga campaigned out of Metemma into Ethiopia; their objective was the town of Gondar. Tekle Haymanot confronted him at Sar Weha on 18 January 1888, but was badly defeated.[1] The Mahdists proceeded to Gondar, and set about ransacking the town. Churches were pillaged and burnt, and many inhabitants were carried away into slavery.

Despite this damage to the historic capital, Emperor Yohannes held back from a counterattack due to his suspicions of Menelik II, then only the ruler of Shewa. He wanted to campaign against Menelik, but the clergy and his senior officers pressed him to handle the Mahdist threat first. The Abyssinians under Ras Gobana Dacche did defeat the Mahdists in the Battle of Guté Dili in the province of Wellega on 14 October 1888. Following this victory the Emperor accepted the advice of his people, and according to Alaqa Lamlam concluded "if I come back I can fight Shoa later on when I return. And if I die at Matamma in the hands of the heathens I shall go to heaven."[2]

Battle

In late January 1889, Yohannes mustered a huge army of 130,000 infantry and 20,000 cavalry in Dembiya. The Sudanese gathered an army of 85,000 and fortified themselves in Gallabat, surrounding the town with a huge zariba, a barrier made of entwined thorn bushes, replicating the effect of barbed wire.

On 8 March 1889 the Ethiopian army arrived within sight of Gallabat, and the attack began in earnest the next day. The wings were commanded by the Emperor's nephews, Ras Haile Maryam Gugsa over the left wing and Ras Mengesha the right.[3] The Ethiopians managed to set the zariba alight, and, by concentrating their attack against one part of the defense managed to break through the Mahdist lines into the town. The defenders suffered heavy losses and were about to break down completely, when the battle turned unexpectedly in their favour.

The Emperor Yohannes, who led his army from the front, had shrugged off one bullet wound to his hand, but a second lodged in his chest, fatally wounding him. He was carried back to his tent, where he died that night; before he died, Yohannes commanded his nobles to recognize his natural son, Ras Mengesha, as his successor.[4] The Ethiopians, demoralized by the death of their ruler, began to melt away, leaving the field—and victory—to the Mahdists.

According to David L. Lewis, the Mahdists were unaware of the Emperor's death until "stench from the rapidly decaying imperial corpse alerted a spy, and the nearly beaten Sudanese thundered out of their zariba to scatter the downcast Ethiopians like starlings."[5] A few days later (12 March) the forces of the Mahdist commander, Zeki Tummal, overtook Rasses Mangasha and Alula and their remaining followers near the Atbara River, who were escorting the Emperor's body to safety. The Mahdists inflicted heavy losses upon the Ethiopians and captured the body of the dead Emperor, whose head they cut off and sent back to Omdurman as a trophy.[6]

Aftermath

The death of the Emperor caused a period of political turmoil in Ethiopia. Although Yohannes on his deathbed named his son Ras Mengesha as his heir, and begged Ras Alula and his other nobles to support him, within a matter of weeks Menelik II was recognized throughout Ethiopia as the new emperor.[7]

For the Mahdists the consequences were severe, as many of their best soldiers had perished in the battle, seriously weakening their military strength. The Khalifa prudently decided to stop offensive actions against Ethiopia and the conflict dwindled to small-scale cross-border raiding.[8]

Notes

- ↑ Bahru Zewde (2001). A History of Modern Ethiopia (second ed.). Oxford: James Currey. p. 59. ISBN 0-85255-786-8.

- ↑ Erlich, Haggai (1996). Ras Alula and the Scramble for Africa. Lawrenceville: Red Sea. p. 133. ISBN 1-56902-029-9.

- ↑ Erlich, Ras Alula, p. 134

- ↑ Erlich (Ras Alula, p. 134) states that until the Emperor's dying declaration, Ras Mangesha had been considered the Emperor's nephew.

- ↑ David L. Lewis, The Race to Fashoda (New York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987), p. 107

- ↑ Erlich, Ras Alula, p. 135f

- ↑ Henze, Paul B. (2000). Layers of Time, A History of Ethiopia. New York: Palgrave. p. 162. ISBN 0-312-22719-1.

- ↑ Churchill Winston, The river war (London, Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1952) p. 83

External links

- "Yohannes IV" ethiopianhistory.com

- Gallabat The 1911 Classic Encyclopedia