Battle of St. Louis

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of St. Louis—Spanish San Luis, also known as the Battle of Fort San Carlos—was an unsuccessful British-led attack on St. Louis (a French settlement in Spanish Louisiana, founded on the west bank of the Mississippi after the Treaty of Paris (1763)) on May 26, 1780, during the Anglo-Spanish War. A force, composed primarily of Indians and led by a former British militia commander, attacked the settlement. The settlement's defenders, mostly local militia, under the command of Lieutenant Governor of Spanish Louisiana Fernando de Leyba, had fortified the town as best they could and successfully withstood the attack.

A second simultaneous attack on the nearby British colonial outpost at Cahokia, on the opposite bank of the Mississippi was also repulsed. The retreating Indians destroyed crops and took captive civilians outside the protected area. The British failure to defend their side of the river effectively ended attempts to gain control of the Mississippi River during the war.

Background

The Spanish entered the American Revolutionary War in 1779. British military planners in London wanted to secure the corridor of the Mississippi River against both Spanish and Patriot activity. Their plans included expeditions from West Florida to take New Orleans and other Spanish targets, and several expeditions to gain control of targets in the upper Mississippi, including the small town of St. Louis. The expedition from West Florida never got off the ground, since Bernardo de Gálvez, the Governor of Spanish Louisiana, had moved rapidly to gain control of British outposts on the lower Mississippi, and was threatening action against West Florida's principal outposts of Mobile and Pensacola.[5][6]

British expedition

The British expeditions from the north were organized by Patrick Sinclair, the military governor at Fort Michilimackinac, in present-day Michigan. Beginning in February 1780 he directed traders to circulate through their territories, recruiting interested tribes for an expedition against St. Louis. The fur traders were offered the opportunity to control the fur trade in the upper parts of Spanish Louisiana as an incentive to participate.[5]

Most of the force gathered at Prairie du Chien, where they were placed under the command of Emanuel Hesse, a former militia captain turned fur trader. The force numbered about two dozen fur traders and an estimated 750 to 1,000 Indians when it left Prairie du Chien on May 2.[2] The largest contingent of the force was about 200 Sioux warriors led by Wapasha, with additional sizable companies from the Chippewa, Menominee, and Winnebago nations, and smaller numbers of warriors from other nations.[2] The Chippewa chief Matchekewis was given overall command of the native forces. When the force reached Rock Island they were joined by about 250 men from the Sac and Fox nations. These warriors were somewhat reluctant to attack St. Louis, but Hesse gave them large gifts to secure their participation in the venture.[7] The diversity within the expedition included some animosity among the tribes, for the Chippewa and Sioux in particular had a history of conflict with each other. However, Wapasha and Matchekewis promoted unity during the expedition.[8]

Spanish and American defenses

The village of St. Louis was primarily a trading hub on the Mississippi River, but it was also the administrative capital of Upper Spanish Louisiana, governed by Lieutenant Governor Fernando de Leyba, a captain in the Spanish Army. Leyba was warned in late March 1780 by a fur trader that the British were planning an attack on St. Louis and the nearby American-held post at Cahokia. He began developing plans for the village's defense. He had only 29 regular army soldiers of the Fijo de Luisiana Colonial Regiment[9] and an inexperienced militia force of 168, most of whom were dispersed in the surrounding countryside.[2]

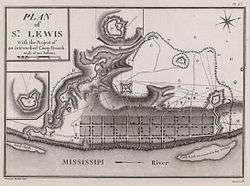

Leyba developed a grand plan of defense that included the construction of four stone towers. Without funds, or the time to get them from New Orleans, Leyba asked the villagers to contribute funds and labor to the construction of these fortifications, and paid for some of the work from his private funds.[10] By mid-May a single round tower had been built that was about 30 feet (9.1 m) in diameter and thirty to forty feet tall. The tower, dubbed Fort San Carlos, provided a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. As there did not appear to be sufficient time to build more towers, trenches were dug between the tower and the river to the north and south of the village.[11] Five cannon were placed on top of the tower,[10] and additional cannon were placed along the trenches.[11]

With a force of only 197 men, 168 of whom were inexperienced militia, it was highly probable that the opposing British-Indian force of 1,000 would overwhelm the Fort San Carlos. However, Leyba appealed to a 70 year old French habitant, Francois Valle, who was located 60 miles to the South of the fort at the site of the French Colonial Valles Mines. Valle sent his two sons and 151 well trained and equipped French militia men which tipped the scale in favor of the defenders. By Royal Decree on April 1, 1782, King Carlos III of Spain, conferred upon Francois Valle the rank of lieutenant in the regular Spanish army thus making him a Spanish don. (citation: Colonial Ste. Genevieve: An Adventure on the Mississippi Frontier written by Carl J. Ekberg, Patrice Pr; 2 Sub Edition, March 1996).

Valle also greatly aided in the Battle of Fort San Carlos because he gave the defenders of both forts a major tactical advantage by supplying them with genuine lead (instead of pebbles or stones) from his mines for musket balls and cannonballs. Getting hit with a pebble or stone did not compare to the damage and knockdown power of a 52-caliber rifle ball at 100 feet. (See France in the American Revolutionary War.)

As a result of his contributions, Francois Valle was called the "Defender of St. Louis".[12]

On May 15, Leyba was visited by John Montgomery, the American commander at Cahokia, who proposed a joint Spanish-American force to counter Hesse's expedition, an idea that did not reach fruition. On May 23, Leyba's scouts reported that Hesse's force was only 14 miles (23 km) away, had landed their canoes, and were coming overland.[1]

Battle

On May 25, Hesse sent out scouting parties to determine the situation at St. Louis. These parties were unable to get close to the village due to the presence of workers, including women and children, in the fields outside the village.[11] The next day Hesse sent Jean-Marie Ducharme and 300 Indians across the river to attack Cahokia, while the remainder headed toward St. Louis, arriving about 1:00 pm. A warning shot was fired from the tower when they came into view, with the Sioux and Winnebagoes leading the way, followed by the Sac and Fox, and the fur traders, including Hesse, bringing up the rear. Leyba directed the defense from the tower, and opened a withering fire from there and the trenches when the enemy force came in range. On the first volley, most of the Sac and Fox fell back, apparently unwilling to fight, leaving many of the other participants suspicious of their motives in joining the expedition and complaining of their "treachery".[13]

Wapasha and the Sioux persisted for several hours in attempts to draw the Spanish defenders out, going so far as brutally killing some captives they had taken in the fields. Although this angered some of the townspeople, to the point where the militia requested permission to make a sortie, Leyba refused. The attackers eventually withdrew and headed north, destroying crops, livestock, and buildings as they went.[13]

On the other side of the river, Ducharme's attack on Cahokia was easily repulsed. The timely arrival of George Rogers Clark to lead its defense played a role: Clark's reputation as a frontier fighter made the Indian force reluctant to pursue the attack.[3]

Aftermath

The village of 700 lost between 50 and 100 killed, wounded, and captured, virtually all civilians.[3] A year later the Spaniards from St. Louis raided Fort St. Joseph, bringing the captured British flag back to St. Louis.[14]

Fernando de Leyba died the following month, the subject of local criticism because he never formally recognized the efforts made by the citizenry in the town's defense.[15] His valor earned him a promotion to lieutenant colonel from King Charles, who did not know that he had died.[16]

Legacy

The site where Fort San Carlos stood is at the corner of Fourth and Walnut Streets in St. Louis. The event is commemorated annually by a local organization who read out the names of the 21 people who lost their lives during the battle.[17] The battle is also remembered in a mural and diorama located in the Missouri State Capitol (pictured).

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Van Ravenswaay, p. 44

- 1 2 3 4 Primm, p. 40

- 1 2 3 Van Ravenswaay, p. 46

- ↑ Van Ravenswaay, p. 45

- 1 2 Nester, p. 279

- ↑ Nester, p. 273

- ↑ Nester, p. 280

- ↑ "Biography of Wahpasha". Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. Retrieved 2013-01-09.

- ↑ "Conflict in the Far North and South". Canadian Military Heritage. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

- 1 2 Van Ravenswaay, p. 43

- 1 2 3 Primm, p. 41

- ↑ http://vallemines.com/OfHistoricalNote/DefenderOfStLouis.aspx[]

- 1 2 Primm, p. 42

- ↑ Primm, p. 45

- ↑ Van Ravenswaay, p. 47

- ↑ Primm, p. 44

- ↑ Rice, Patricia. "Group fights for recognition of little-known 1780 Battle of St. Louis". West End Word. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

References

- Gilman, Carolyn. "L'Anneé du Coup: The Battle of St. Louis, 1780 Part 2," Missouri Historical Review (2009) 103#4 pp: 195-211

- Primm, James Neal (1998). Lion of the Valley: St. Louis, Missouri, 1764–1980. St. Louis, MO: Missouri History Museum. ISBN 978-1-883982-24-9. OCLC 245700335.

- Nester, William R (2004). The Frontier War for American Independence. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0077-1. OCLC 260092836.

- Van Ravenswaay, Charles (1991). Saint Louis: an Informal History of the City and its People, 1764–1865. St. Louis, MO: Missouri History Museum. ISBN 978-0-252-01915-9. OCLC 24431022.