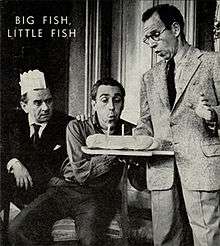

Big Fish, Little Fish (play)

Big Fish, Little Fish is a comedy in three acts by playwright Hugh Wheeler. The story concerns a former college professor, disgraced by a sex scandal, who now works in a minor post at a publishing company. The play explores his relationships with his parasitic group of friends and treats issues of homosexuality, guilt and friendship. The work was Wheeler's first play, and afterwards he turned to playwriting full-time.[1]

After an out-of-town tryout in Philadelphia beginning on February 27, 1961,[2] the piece premiered on March 15 at ANTA Playhouse on Broadway in New York City.[3] The production was directed by John Gielgud. It ran for 101 performances, closing on July 10, 1961.[4] The production did not make money at the box office,[5] but despite only mixed to warm reviews, it won two Tony awards, Best Director and Best Featured Actor, and was nominated for two more. A London production the following year was a failure, closing within two weeks. The piece has rarely been revived, but it was adapted for television in 1971.

Big Fish, Little Fish was one of the first Broadway plays to explore frankly the issue of homosexuality,[6] and Gielgud ignored advice to tone down the "implicit queerness."[7] Hume Cronyn kept a diary of the original production. He reported that, during rehearsals, the cast and creative team engaged in long discussions about the homosexuality theme. He commented that attempts to "prejudge audience or critical reaction" could lead to a "safe but regretful" production. Cronyn praised Gielgud's process and his abilities as a "director-analyst." He also praised the talent, creativity and generosity of Wheeler and of the other actors in the cast.[2]

Cast

- Jimmie Luton – Hume Cronyn

- William Baker – Jason Robards

- Basil Smythe – Martin Gabel

- Ronnie Johnson – George Grizzard

- Paul Stumpfig – George Voskovec

- Edith Maitland – Ruth White

- Hilda Rose – Elizabeth Wilson

Plot

The setting is William Baker's New York apartment in the East 30s. The time is the present (1961).[3]

William has worked in a minor position in a publishing firm for more than two decades. Before that he was a rising academic, the youngest full professor at a prestigious university. He was forced out of the post after a scandal: a young student broke into his rooms and committed suicide, leaving a note claiming that William seduced and then abandoned him. William's denials were not believed.[8]

His middle-aged circle of friends, who all have emotional demands on him, are Edith, a married woman with whom he sometimes sleeps; Jimmie, a schoolmaster with cultural aspirations and a crush on William;[9] Basil, a retired publisher and lonely cat-lover; Hilda, a minor executive who aspires to be racy; and Viola a former lover of William's, who is not seen but rings him frequently, usually when drunk.[10] William is kind and sweet to his friends, but it is not clear how much he depends emotionally on being a big fish in a small pond.[11]

William's friends bicker with one another and sometimes with him, but the group is generally stable until the arrival of Ronnie, an ambitious young author.[12] He has been asked to find someone to fill an unexpected senior vacancy in a publishing company in Geneva, and he successfully seeks to interest William in the post. Most of William's friends resist, then accept with sadness, the prospect of his departure for Europe, but Basil is devastated and suffers a fatal heart attack from the shock.[13]

Shortly before his departure for Geneva, in conversation with Jimmie, William confesses that he was not the victim of an injustice at the university: the student's accusation was true. He has been working in a lowly position ever since as a form of penance and expiation.[14]

The Swiss appointment falls through at the last minute.[15] William nevertheless announces his intention to go to Europe on holiday, hosting a farewell party where he expresses his unhappiness with his friends. It is left ambiguous as to whether he will return to resume his place at the center of his New York circle. The play ends with him once more soothing Viola over the phone.[16]

Critical reception

Reviewing the premiere for The New York Times, Howard Taubman wrote, "There is a softness at the core of the play because there is a disquieting elusiveness about the central character. If you can believe in him, and Jason Robards Jr. makes a brilliant effort to turn him into a credible human being, you may find the essential story deeply moving. But if you can't, the work goes soggy. … Mr. Wheeler has not always steered a straight, clear course. But he writes of strange relationships with an integrity that is occasionally beguiling."[17] The New York correspondent of The Times praised the virtuosity of the cast and director, and said of the play, "Still, good parts require to be written, and Mr. Wheeler, hitherto known only as a writer of detective novels ... has written them. And yet these characters are, in a sense, set adrift by their intense devotion to the less interesting character played by Mr. Robards and by their old isolation from the rest of the world."[18] In Theatre Journal, John Gassner shared his view that the central role was not the strong point of the play, but he praised both Wheeler and Cronyn for their sensitive and honest treatment of Jimmie's hidden homosexuality.[19]

Later productions

The play opened at the Duke of York's Theatre in London's West End on 18 September 1962, directed by Frith Banbury, with Hume Cronyn as Jimmie, Thomas Coley as William, Frank Pettingell as Basil, Frederick Jaeger as Ronnie, Carl Jaffé as Paul, Jessica Tandy as Edith and Viola Lyel as Hilda. The production closed less than two weeks later, on 29 September 1962.[20]

A television version was broadcast in the US in January 1971, with William Windom, Louis Gossett, Jr. and Bill Bixby leading the cast.[21] An Off-Off-Broadway production ran in 1974.[22]

Awards

The production won two Tony awards for the Broadway production, Gabel as Featured Actor, and Gielgud as Director, and was nominated for two more, Cronyn as Best Actor, and Grizzard as Featured Actor.[4][23]

Notes

- ↑ Hampton, Wilborn. Obituary: "Hugh Wheeler, Award Winning Playwright", The New York Times, July 28, 1987, retrieved March 14, 2014

- 1 2 Cronyn, Hume. "Dear Diary", Theatre Arts Magazine, July 1961, reproduced in Senelick, pp. 74–82

- 1 2 Wheeler, unnumbered introductory page

- 1 2 "Big Fish, Little Fish", Internet Broadway Database, retrieved 14 March 2014

- ↑ Bordman, p. 375

- ↑ Senelick, p. 74

- ↑ Croall, p. 463

- ↑ Wheeler, p. 48

- ↑ Wheeler, pp. 3–5

- ↑ Wheeler, p. 13

- ↑ Wheeler, p. 5

- ↑ Wheeler, p. 33

- ↑ Wheeler, p. 100

- ↑ Wheeler, p. 105

- ↑ Wheeler, p. 109

- ↑ Wheeler, p. 115

- ↑ Taubman, Howard. "The Theatre: Odd Circle; Robards and Cronyn in Big Fish, Little Fish", The New York Times, 16 March 1961, p. 42 (subscription required)

- ↑ "Not so dramatic on Broadway", The Times, 1 May 1961, p. 16

- ↑ Gassner, John. "Broadway in Review", Theatre Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2 (May 1961), p. 106 (subscription required)

- ↑ "Theatres", The Times, 29 September 1962, p. 2; and 1 October 1962, p. 2

- ↑ Gussow, Mel. "Big Fish, Little Fish returns", The New York Times, 6 January 1971, p. 75 (subscription required)

- ↑ Thompson, Howard. "Mainstream Drama Runs In Big Fish, Little Fish", The New York Times, 18 September 1974, p. 32 (subscription required)

- ↑ "Big Fish, Little Fish", Tony Awards, retrieved March 14, 2014

References

- Bordman, Gerald (1996). American Theatre: A Chronicle of Comedy and Drama, 1930–1969. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195358082.

- Croall, Jonathan (2011). John Gielgud: Matinee Idol to Movie Star. A & C Black. ISBN 1408131072.

- Senelick, Laurence (2013). Theatre Arts on Acting. Routledge theatre classics. ISBN 113472375X.

- Wheeler, Hugh (1961). Big Fish, Little Fish – A New Comedy. London: Rupert Hart-Davis. OCLC 11219792.

External links

- "Big Fish, Little Fish" at Playbill Vault

- "Big Fish, Little Fish" at Broadway Internet Database]