Km (hieroglyph)

| ||

| "I6", Crocodile skin with spines in hieroglyphs |

|---|

The Egyptian hieroglyph for "black" in Gardiner's sign list is numbered I6. Its phonetic value is km. The Wörterbuch der Aegyptischen Sprache-(Dictionary of the Egyptian Language) lists no less than 24 different terms of km indicating 'black' such as black stone, metal, wood, hair, eyes, and animals.[1]

The most common explanation for the hieroglyph is under the Gardiner's Sign List, section I for "amphibious animals, reptiles, etc" is a crocodile skin with spines. Rossini and Schumann-Antelme propose that the crocodile skin hieroglyph actually shows claws coming out of the hide.[2]

Besides 'black', the alternate use of the hieroglyph is for items terminating, coming-to-an-end, items of completion, hence a reference to charcoal, burning to its ending.[3]

km.t

(Egyptian: km-m-t, with "City-Region" determinative, " kmt ")

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the Demotic (Egyptian) text of the Rosetta Stone, the demotic for Egypt is 'Kmi' . There are three uses of the actual Kmi, but 7 others referenced as Kmi refer to iAt in the hieroglyphs. Other euphemistic references to Egypt in the Rosetta Stone include "Ta-Mer-t", which has the meaning of the 'full/fruitful/cultivated land', hr-tAwy, the 'lands of Horus', and tAwy, the "Two Lands."

- Kmi—spelling-"Egypt" —(22 places, synchronized, Demotic–Hieroglyphs)

|

|

Egyptian word examples, conclusion, completion, kmt, km iri

| ||||||||||||||

| "conclusion" and "to total"--("complete") --"kmt"--and--"km iri"-- in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Coming to a conclusion, or completion is one use of the km hieroglyph in the words kmt and km iri ('to make an end').[7] The discussion of the biliteral states: The conclusion of a document, written in black ink, ending the work, has the same semantic connotation.[8] (as km for 'concluding') The Rossini, Schumann-Antelme write-up states that initially the word comes from "shield", ikm, and thus the original association with the crocodile.[8]

Alternative glyph, X5 equivalent, items burning black to an ending

| ||

| "burning flames, on charcoal" in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Since the origin of the 'black' hieroglyph, and relationships to other forms showing vertical flame-like rises on the end of a flat-triangular shape, there has been discussion of this hieroglyph. As stated above, Schumann-Antelme and Rossini explain the crocodile skin, but with claws.[8] The text by Egyptologists Mark Collier and Bill Manley describes the same "crocodile skin", Gardiner I6, as burning charcoal with flames.[9]

Skin, I6 entry in 1920 Budge "dictionary"

|

|

The last three of four entries ending the 27 entries deal with black stones, or powders and black plants, or seeds; (all small multiple, plural, grains-of, items). They are preceded by entries 21 and 22, a "buckler", or "shield", and "black wood". Entry 26 is an image, or statue, using the vertical mummy hieroglyph gardiner A53, ("in the form of", "the custom of"). These last six entries are unreferenced.

The first 4 of 5 entries, kam, kam-t, or kamkam all deal with items coming to an end. (Entry four is untranslated and is from Pap. 3024, Lepsius, Denkmaler-(papyrus).) The references for the others in the first five are: Peasant, Die Klagen des Bauern, 1908.,[11] Thes.-(Thesaurus Inscriptionum Aegyptiacarum, Brugsch);.[12] A. Z.-(twice);[13] Shipwreck., 118-(Tale of the shipwrecked sailor);[14] Amen.-(author: Amen-em-apt);[15] and Thes. (again).

Entries 6 to 20 deal with "black" or gods, or named items. Only 8 of these items reference black, but start by also referring to Coptic. Entries 6, 7, and 8 refer to coptic "KAME", for 6 and 8; entry 7 to coptic "KMOM", "KMEM". For entry 7, to be black, Budge also references Revue-(Rev.);[16] for entry 8, black items, Budge also references T.-(King Teta);[17] and N.-(Pepi II-(King Nefer-ka-Ra).[18] The other hieroglyph word entries of entry 9 to 20, have about fifteen further references, all starting with the km hieroglyph.

On the other hand, the works of Budge have not held up well in terms of recent hieroglyph scholarship since the 1930s. Even during Budge's own lifetime, many Egyptological scholars disputed Budge's interpretation of glyphs and texts.[19] Today, no modern Egyptological scholar relies upon the works of E. A. W. Budge as evidence of proper glyph rendering, by either his translation or transliteration (his transliteration system was unique to Budge alone as most Egyptologists then (and today) relied upon the transcription and transliteration system developed by the Berlin School which issued the master compendium of Egyptian hieroglyphic language in 1926, Wörterbuch der Aegyptischen Sprache (7 Vols.),[20] and which is detailed in the publication by A. H. Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs (1957)). As such, references to Budge's dictionary and within Budge's dictionary are considered highly suspect by most Egyptologists today, as they do not actually relate back to the terms as he defined them.

Shield

| ||||||||||||

| "shield" and "to put an end to" --"ikm"--and--'khm-- in hieroglyphs |

|---|

"Shield", ikm and another word with an approximate km cognate, 'khm starting with the vowel ( ' ), 'khm, meaning to put to an end are the possible words related to the origins of the crocodile skin, and the 'verb of action', of items coming to an end. The second word 'khm has nine entries in the Budge dictionary,[21] shield, ikam, has two entries.[22]

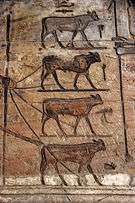

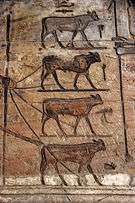

The 4th cow is labelled, black

The 4th cow is labelled, black

(variant "triangle-hieroglyph" with "flames") Obelisk of Nectanebo II-

Obelisk of Nectanebo II-

(crocodile skin hieroglyph)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crocodile skin (hieroglyph). |

- Gardiner's Sign List#I. Amphibious Animals, Reptiles, etc.

- Kemeticism

- Kemet

- Kmt

- Mnewer, the black bull: "Black-Great (One)", Kemwer-(Km-wr)

References

- ↑ Wörterbuch V: 122-124)

- ↑ Schumann-Antelme, Rossini, Illustrated Hieroglyphics Handbook, p 140.

- ↑ Collier-Manley, How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs, Other small signs-D8', Sign D8, crocodile skin glyph, "burning charcoal with flames", p. 138.

- ↑ Gardiner 2005 (1957): 498.

- ↑ Ptolemaic Lexicon (Wilson 1997: 36, indicating is as a euphemism for the land after the inundation subsided.

- ↑ Wörterbuch (Erman and Grapow 1926, "I": 26, 13), indicating it as a collateral term for exposed fertile black land of Egypt.

- ↑ Schumann-Antelme, Rossini, Illustrated Hieroglyphics Handbook, p 140-141.

- 1 2 3 Schumann-Antelme, Rossini, p. 140.

- ↑ Collier-Manley, How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs, Other small signs-D8, p. 138.

- ↑ Budge, An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, volume 2, p 787B, 788A.

- ↑ Budge, An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, Principal Works used in Preparation of Dictionary, p. lxxxv.

- ↑ Budge, Ibid. p. lxxxviii.

- ↑ Budge, Ibid. (Zeitschrift fur Agypttische Sprache und Alterthumskunde, in progress) p. lxxxviii.

- ↑ Budge, Ibid. (Shipwreck.), p. lxxxvii.

- ↑ Budge, Ibid. "The Book of Precepts of Amen-em-apt, the son of Ka-nekht", according to the Papyrus in the British Museum, p. lxxvii;

- ↑ Budge, Ibid. Revue, 13, 15, 14, 10; Revue Egyptologique publiee sous la direction de MM. Brugsch, F. Chabas, and Eug. Revillout, p. lxxxvi.

- ↑ Budge, Ibid. T 26, King Teta, funerary texts published by Maspero, p. lxxxvii.

- ↑ Budge, Ibid. N 208, King Nefer-ka-Ra, (Pepi II), funerary texts published by Maspero, p. lxxxvii.

- ↑ D. Forbes 1997: 79

- ↑ Bierbrier 1995: 72

- ↑ Budge, An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, p. 135B, p. 136A.

- ↑ Budge, Ibid., p. 94A.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Black (hieroglyphic 'km'). |

External links

Further reading

- Bierbrier, M. 1995. Who Was Who in Egyptology. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

- Budge. An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, E.A.Wallace Budge, (Dover Publications), c 1978, (c 1920), Dover edition, 1978. (In two volumes) (softcover, ISBN 0-486-23615-3)

- Collier, Mark, and Manley, Bill, How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs, c 1998, University of California Press, 179 pp, (with a word Glossary, p 151-61: Title Egyptian-English vocabulary; also an "Answer Key", 'Key to the exercises', p 162-73) {hardcover, ISBN 0-520-21597-4}

- Erman, A. and H. Grapow 1926. Wörterbuch der Aegyptischen Sprache. (7 Vols.) Leipzig: J. C. Hinrich.

- Forbes, D. 1997. Giants of Egyptology: E.A. Wallis Budge (1857–1943). KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt 8/2 (Summer 1997): 78-80.

- Gardiner, A. H. 2005 (1957). Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs. Oxford: Griffith Institute.

- Hannig, R. 1995. Die Sprache der Pharaonen: Großes Handwörterbuch Ägyptisch-Deutsch (2800 - 950 v. Chr.). Kulturegeschichte der Antiken Welt 64. Mainz: von Zabern.

- Schumann-Antelme, and Rossini, 1998. Illustrated Hieroglyphics Handbook, Ruth Schumann-Antelme, and Stéphane Rossini. c 1998, English trans. 2002, Sterling Publishing Co. (Index, Summary lists (tables), selected uniliterals, biliterals, and triliterals.) (softcover, ISBN 1-4027-0025-3)

- Wilson, P. 1997. A Ptolemaic Lexikon. A Lexographical Study of the Texts of the Temple of Edfu. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 78. Leuven: Peeters/Department of Oosterse Studies.