Bob Hoover

| Robert A. Hoover | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Bob |

| Born |

January 24, 1922 Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died |

October 25, 2016 (aged 94) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1940–1948 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit |

52d Fighter Group Flight Evaluation Group |

| Battles/wars |

World War II Korean War |

| Awards |

Distinguished Flying Cross Soldier's Medal for Valor Air Medal with Clusters Purple Heart Croix de guerre |

| Other work | Test and air show pilot |

Robert Anderson "Bob" Hoover (January 24, 1922 – October 25, 2016) was an air show pilot, United States Air Force test pilot, and fighter pilot.[1] Known as the "pilot's pilot", Hoover revolutionized modern aerobatic flying and has been referred to in many aviation circles as one of the greatest pilots ever to have lived.[2][3][4][5]

Aviation career

Hoover learned to fly at Nashville's Berry Field while working at a local grocery store to pay for the flight training.[6] He enlisted in the Tennessee National Guard and was sent for pilot training with the Army.[7]

During World War II, Hoover was sent to Casablanca, where his first major assignment was flight testing the assembled aircraft ready for service.[8] He was later assigned to the Spitfire-equipped 52d Fighter Group in Sicily.[9] On February 9, 1944, on his 59th mission, his malfunctioning Mark V Spitfire was shot down by 96-victory ace Ltn Siegfried Lemke of Jagdgeschwader 2[10] in a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 off the coast of Southern France, and he was taken prisoner.[11] He spent 16 months at the German prison camp Stalag Luft 1 in Barth, Germany.[12]

After a staged fight covered his escape from the prison camp, Hoover managed to steal a Fw 190 from a recovery unit's unguarded field — the one flyable plane being kept there for spare parts — and flew to safety in the Netherlands.[13] He was assigned to flight-test duty at Wilbur Wright Field after the war. There he impressed and befriended Chuck Yeager.[14] When Yeager was later asked whom he wanted for flight crew for the supersonic Bell X-1 flight, he named Hoover. Hoover became Yeager's backup pilot in the Bell X-1 program and flew chase for Yeager in a Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star during the Mach 1 flight.[15] He also flew chase for the 50th anniversary of the Mach 1 flight in a General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon.[16]

Hoover left the Air Force for civilian jobs in 1948.[17] After a brief time with Allison Engine Company, he worked as a test/demonstration pilot with North American Aviation, in which capacity he went to Korea to teach pilots in the Korean War how to dive-bomb with the F-86 Sabre. During his six weeks in Korea, Hoover flew many combat bombing missions over enemy territory, but was denied permission to engage in air-to-air combat flights.[18]

During the 1950s, Hoover visited many active-duty, reserve, and Air National Guard units to demonstrate planes' capabilities to their pilots. Hoover flew flight tests on the FJ-1 Fury, F-86 Sabre, and the F-100 Super Sabre.

In the early 1960s, Hoover began flying the North American P-51 Mustang at air shows around the country. The Hoover Mustang (N2251D) was purchased by North American Aviation from Dave Lindsay's Cavalier Aircraft Corp. in 1962. A second Mustang (N51RH), later named "Ole Yeller", was purchased by North American Rockwell from Cavalier in 1971 to replace the earlier aircraft, which had been destroyed in a ground accident when an oxygen bottle exploded after being overfilled. Hoover demonstrated the Mustang and later the Aero Commander at hundreds of air shows until his retirement in the 1990s. In 1997, Hoover sold "Ole Yeller" to his good friend John Bagley of Rexburg, Idaho. "Ole Yeller" still flies frequently and is based at the Legacy Flight Museum[19] in Rexburg.

Hoover set records for transcontinental and time-to-climb, speed,[20] and personally knew such great aviators as Orville Wright, Eddie Rickenbacker, Charles Lindbergh, Jimmy Doolittle, Chuck Yeager, Jacqueline Cochran, Neil Armstrong, and Yuri Gagarin.[21]

Hoover was best known for his civil air show career, which started when he was hired to demonstrate the capabilities of Aero Commander's Shrike Commander, a twin piston-engined business aircraft that had developed a rather staid reputation due to its bulky shape. Hoover showed the strength of the plane as he put the aircraft through rolls, loops, and other maneuvers, which most people would not associate with executive aircraft. As a grand finale, he shut down both engines and executed a loop and an eight-point hesitation slow roll as he headed back to the runway. He touched down on one tire, then the other, before landing. After pulling off the runway, he would start engines to taxi back to the parking area. On airfields with large enough parking ramps (such as the Reno Stead Airport, where the Reno Air Races take place), Hoover would sometimes land directly on the ramp and coast all the way back to his parking spot in front of the grandstand without restarting the engines.

End of career

His air show aerobatics career ended in 1999, but was marked by issues with the FAA over his medical certification that began when Hoover's medical certificate was revoked by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the early 1990s.[22][23]

Shortly before his revocation, Hoover experienced serious engine problems in a North American T-28 Trojan off the coast of California. During his return to Torrance, he was able to keep the engine running intermittently by constantly manipulating the throttle, mixture, and propeller levers. The engine seized at the moment of touchdown. Hoover believed his successful management of this difficult emergency should have convinced the FAA that he hadn't lost any ability.[24] Meanwhile, Hoover was granted a pilot's license, and medical certificate, by Australia's aviation authorities.[25] Hoover's medical certificate was restored shortly afterward and he returned to the American air show circuit for several years before retiring in 1999. The 77-year old Hoover still felt capable of performing and had recently passed a rigorous FAA physical, but he was unable to obtain insurance for air shows. Although he had had free insurance for several years as part of air show sponsorship deals, he was forced in 1999 to pay for it out of his own pocket and could not get coverage under $2 million. His final show was Sun'N'Fun 2000 in Lakeland, Florida, where he did not perform any aerobatics.[23]

Following Hoover's retirement, his Shrike Commander was placed on display at the National Air and Space Museum, Udvar-Hazy Center, in Dulles, Virginia.[26]

Honors and recognition

Hoover was considered one of the founding fathers of modern aerobatics and was described by Jimmy Doolittle as "the greatest stick-and-rudder man who ever lived".[27] In the Centennial of Flight edition of Air & Space/Smithsonian, he was named the third greatest aviator in history.

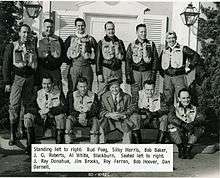

During his career, Hoover was awarded the following military medals: the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Soldier's Medal for non-combat valor, the Air Medal with several oak leaf clusters, the Purple Heart, and the French Croix de Guerre.[28] He was also made an honorary member of the Blue Angels, the Thunderbirds, the RCAF Snowbirds, the American Fighter Aces Association, and the original Eagle Squadron, and received an Award of Merit from the American Fighter Pilots Association.[28] He was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1988 and to the Aerospace Walk of Honor in 1992.[29]

Hoover received the Living Legends of Aviation Freedom of Flight Award in 2006, which was renamed the Bob Hoover Freedom of Flight Award the following year. In 2007, he received the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum Trophy.[27][30]

On May 18, 2010, Hoover delivered the 2010 Charles A. Lindbergh Memorial Lecture at the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School conferred an honorary doctorate on Hoover at the school's December 2010 graduation ceremony.[31] Flying magazine placed Hoover number 10 on its list of "The 51 Heroes of Aviation" in 2013.[2]

On December 12, 2014, at the Aero Club of Washington's 67th annual Wright Memorial Dinner, Hoover was awarded the National Aeronautic Association's Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy.

Flying the Feathered Edge: The Bob Hoover Project

Hoover's decades of fantastic flying formed the framework for the 2014 documentary film, Flying the Feathered Edge: The Bob Hoover Project, in which Hoover's likeable personality was the star. Hoover received a standing ovation from the crowd of about 100 at the invitation-only preview during EAA AirVenture Oshkosh, July 2014.[32]

Harrison Ford and aerobatic legend Sean D. Tucker frame the documentary about the beloved aviation pioneer.[33] The film begins with a tribute to Bob's flying skills by Neil Armstrong, and it stars Harrison Ford, Burt Rutan, Dick Rutan, Carroll Shelby, Gene Cernan, Medal of Honor Recipient Col. George E. Bud Day, Clay Lacy, and Sean D. Tucker, among others.[34]

Flying the Feathered Edge is a highly researched three-year project.[35] The film tells Hoover's story from his first flying lessons before World War II to his combat and postwar careers as a test pilot and air show legend.[34] Aviation Week reporter Fred George's review stated, "After 90 minutes there were few dry eyes in the house as the credits rolled at the end of the documentary ... in 'Aviation Week''s opinion, a film well worth our reader's viewing time when it appears in nearby theaters."[36]

The film premiered August 2014 at the Rhode Island International Film Festival at the Veterans Memorial Auditorium (Providence) in Providence, Rhode Island,[34] winning the "Grand Prize, Soldiers and Sacrifice Award."[37] The film received the Combs/Gates Award from the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2015 [38] for excellence in preserving aerospace history.

Hoover Nozzle and Hoover Ring

A perhaps-undesired recognition for the late pilot is the "Hoover Nozzle" used on jet fuel pumps. The Hoover Nozzle is designed with a flattened bell shape. The Hoover Nozzle cannot be inserted in the filler neck of a plane with the "Hoover Ring" installed, thus preventing the tank from accidentally being filled with jet fuel.

This system was given this name following an accident in which Hoover was seriously injured, when both engines on his Shrike Commander failed during takeoff. Investigators found that the plane had just been fueled by line personnel who mistook the piston-engine Shrike for a similar turboprop model, filling the tanks with jet fuel instead of avgas (aviation gasoline).[39] There was enough avgas in the fuel system to taxi to the runway and take off, but then the jet fuel was drawn into the engines, causing them to stop.

Once Hoover recovered, he widely promoted[40] the use of the new type of nozzle with the support and funding of the National Air Transportation Association, General Aviation Manufacturers Association, and various other aviation groups (the nozzle is now required by Federal regulation on jet fuel pumps).[41][42]

References

Notes

- ↑ Collins, Bob (October 25, 2016). "Bob Hoover, one of history's greatest pilots, dead at 94". MPR News. Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- 1 2 "51 Heroes of Aviation." Flying. Retrieved: May 3, 2015.

- ↑ The Bob Hoover Project: Flying the Feathered Edge. Documentary video. Retrieved: May 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Robert A. “Bob” Hoover, The Greatest Stick and Rudder Man, is Honored in Hollywood". AirSpace Blog. Retrieved: July 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Bob Hoover; considered one of the greatest pilots in world". The Boston Globe. Retrieved: October 28, 2016.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, p. 17.

- ↑ Hoover. Forever Flying. p. 37.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, p. 50.

- ↑ http://bbs.hitechcreations.com/smf/index.php?topic=277903.0

- ↑ Hoover 1997, pp. 65–67.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, p. 90.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, pp. 88–90.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, p. 93.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, p. 110.

- ↑ "Hoover Flys Chase for Yeager." Ohio University Post, October 15, 1997. Retrieved: November 29, 2008.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, p. 137.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, pp. 187–189.

- ↑ "Library of Planes: Old Yeller." Archived May 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Legacyflightmuseum.com. Retrieved: June 24, 2013.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, pp. 251–253.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, p. 247.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, pp. 278–279.

- 1 2 Jordan, Jon L., MD, JD. "The Federal Air Surgeon's Column: Bob Hoover, the facts." Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved: July 19, 2015.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, p. 280.

- ↑ Hoover 1997, pp. 281–282.

- ↑ "North American Rockwell Shrike Commander 500S, Robert A. "Bob" Hoover." Archived July 21, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved: June 25, 2013.

- 1 2 "Robert A. "Bob" Hoover and Hale, STS-121 Shuttle Team are Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum Trophy Winners>" Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, March 7, 2007. Retrieved: November 29, 2008. Archived March 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Hoover 1997, p. xiii.

- ↑ "Hoover Biography." Archived December 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Aerospace Walk of Honor, City of Lancaster, California. Retrieved: November 29, 2008.

- ↑ "Recipients of the National Air and Space Museum Trophy." Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved: July 9, 2015.

- ↑ "That's Dr. Hoover to You." Air & Space/Smithsonian, Volume, 25, Issue 7, February–March 2011, p. 11. ISSN 0886-2257

- ↑ "Bob Hoover Documentary Preview Screening at AirVenture Warmly Received." Oshkosh Daily Paper, July 25, 2014.

- ↑ FilmStew.com, Harrison Ford Frames Documentary About Beloved Aviation Pioneer, July 30, 2014

- 1 2 3 "Bob Hoover documentary premieres Aug. 10." General Aviation News, August 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Flying The Feathered Edge." The Bob Hoover Project, July 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Things with Wings: Hoover Bio Pic Premiers at AirVenture." Aviation Week Blog, July 30, 2014.

- ↑ "RIIFF Awards, 2014 Film Festival Award Winners Announced." film-festival.org, August 10, 2014.

- ↑ "AOPA.com", November 19, 2015

- ↑ Hoover 1997, pp. 275–277.

- ↑ "Six aviation legends to be recognized as 'Master Pilots'." Aviation Online Magazine, September 19, 2010. Retrieved: June 24, 2013.

- ↑ "The Causes and Remedies of Aviation Misfueling." Federal Aviation Administration, July–August 2005, p. 20. Retrieved: June 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Aircraft Misfueling – A Continuing Threat." NATA Safety 1st eToolkit, July 18, 2006, p. 1. Retrieved: June 24, 2013.

Bibliography

- Hoover, Robert A. Forever Flying:Fifty Years of High-Flying Adventures, From Barnstorming in Prop Planes to Dogfighting Germans to Testing Supersonic Jets: An Autobiography. New York: Pocket Books, 1997. ISBN 978-0-67153-761-6.

External links

- Bob Hoover: A Legendary Stick and Rudder Man | National Air and Space Museum

- The Bob Hoover Project: Flying the Feathered Edge

- Biography in the National Aviation Hall of Fame

- Biography in Airport Journals

- Aviation Legend Bob Hoover dies at 94

- Bob Hoover video in which he pours tea while performing an aileron roll from Amelia's Landing Hotel aviation video library

- Hoover 2005 Gathering of Eagles Biography

- Hoover obituary via The New York Times