Bosnian-Herzegovinian Infantry

The Bosnian-Herzegovinian Infantry (Bosnisch-Hercegovinische Infanterie), commonly called the Bosniaken (German for Bosniaks),[lower-alpha 1] were a branch of the Austro-Hungarian Army. Recruited from outside the Austrian and Hungarian regions of the Dual-Monarchy, with a significant proportion of Muslim personnel (31.4%), these regiments enjoyed a special status. They had their own distinctive uniforms and were given their own numbering sequence within the Common Army (KuK).

The units were part of the Austro-Hungarian infantry in 1914 and consisted of four infantry regiments (numbered 1-4) and a Field Rifles Battalion (Feldjägerbataillon).[1]

Background

The Congress of Berlin of 1878 assigned two Ottoman provinces, the Vilayet of Bosnia and the Sanjak of Novi Pazar to administration by Austro-Hungary. In July of the same year Austrian troops began the occupation of the two provinces but encountered widespread resistance from the Muslim population of Bosnia.[2] During a campaign that lasted until October 1878 the Austrian forces suffered casualties of 946 dead and 3,980 wounded.[3]:135

Although the two provinces constitutionally still belonged to the Ottoman Empire, the Austrian Imperial Administration began to build up a rudimentary administrative apparatus based on a reform of the existing systems. There was ongoing communal tension and resistance to Habsburg rule in many rural areas, especially in Herzegovina and along the eastern border with Montenegro. "The Austrians set up a special local militia force there, the 'Pandurs'; but many of these militia men became rebellious themselves, and some took to brigandage."[3]:138

"In November 1881 the Austro-Hungarian government passed a Military Law (Wehrgesetz) imposing an obligation upon all Bosnians to serve in the Imperial Army."[4] This led to widespread riots over December 1881 and throughout 1882 - which could only be defeated and suppressed by military means. The Austrians appealed to the Mufti of Sarajevo, Mustafa Hilmi Hadžiomerović (born 1816) and he soon issued a Fatwa "calling on the Bosniaks to obey military Law."[5] Other important Muslim community leaders such as Mehmedbeg Kapetanović, later Mayor of Sarajevo, also appealed to young Muslim men to serve in the Habsburg military.

Creation

Infantry formations were first set up in 1882 in each of the four main areas of Sarajevo, Banja Luka, Tuzla and Mostar. Initially each was composed of one infantry company which was enlarged in subsequent years by a company each. By 1889 there were eight independent battalions. In 1892 three more battalions were established. In 1894 the military administration set up the Bosnian Herzegovinian Infantry Regiment Association (Bosnisch-Hercegowinische Infanterie den Regimentsverband) in order to integrate them into the rest of the Imperial Austrian army. On 1 January 1894 a "Most High Resolution" (Allerhöchste Entschließung) formalised this measure but it proved to be difficult and was not completed until 1897.

The Field Rifles Battalion (Feldjägerbataillon) was established in 1903.

Composition

Immediately prior to the outbreak of World War I the four Bosnian-Herzegovian infantry regiments numbered 10,156 men (plus 21,327 reservists).[6] The Field Rifles Battalion comprised 434 serving jägers, with 1,208 reservists. In January 1913 31.4% of NCOs and other ranks were Muslims, 39.8% Serbian Orthodox and 25.4% Roman Catholic. The remainder were a mix of Greek Catholics, Jews and Protestants.[7] Regardless of religious faith all other ranks wore the fez.

World War I

In the course of the war the Bosnian-Herzegovian infantry regiments (including jägers) expanded to a maximum of 35 battalions. Each had a strength of about 1,000 men when at full strength.[8] The pressures of heavy casualties led to a breakdown of rigid regional recruitment after 1915, with Hungarian, Polish, Czech and Ukrainian troops serving in Bosnian units, while Bosnians were drafted into the nominally German and Hungarian regiments of the K.u.K. Army.[9] Inevitably this diversity led to a dilution of the effectiveness of individual units but the Bosnian-Herzegovian regiments retained a high reputation for loyalty and effectiveness until the very end of the war.

In 1916 Austria-Hungary occupied Albania and about 5,000 Albanian men were recruited "to serve in a militia with Bosnian Muslim officers."[10]

Captain Gojkomir Glogovac was awarded Austria-Hungary's highest military honour, the Military Order of Maria Theresa, for extreme bravery in 1917; he was subsequently ennobled as Baron Glogovac. Another prominent Bosnian officer to rise in the ranks was Colonel Hussein Biscevic (Husein Biščević or Biščević-beg) who later served in the Waffen SS.[11] Muhamed Hadžiefendić (1898–1943) served as a lieutenant in a Bosnian-Herzegovian unit during World War I.

Uniform

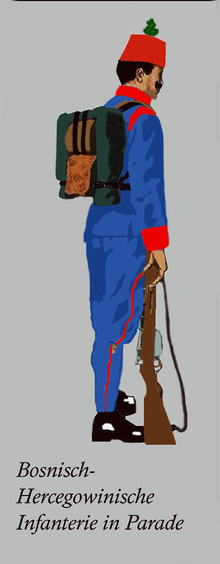

Bosnian infantry regiments had several uniform features which distinguished them from other units of the Austro-Hungarian army. The most distinctive of these garments was the Oriental fez, which was worn both on parade and in field uniform. The fez was made of reddish-brown felt and equipped with a tassel of black sheep's wool. This tassel was 18.5 cm long and mounted on a rosette fringes. The fez had to be worn so that the tassel was at the back. Officers and cadets usually wore standard Austrian military infantry rigid black caps or full-dress shakos. However, if officers were Muslim, they had the option of wearing the fez. Tunics and blouses were consistent with those of the standard "German" line infantry of the K.u.K. Army. The buttons were of bronze metal, carrying the appropriate regimental number. Officers' uniforms consisted of light blue tunics, with red collar and yellow buttons, and light blue trousers.

Ordinary soldiers had a light blue uniform with red facings. Included were widely cut oriental-style breeches, which narrowed below the knee (see coloured illustrations above).[12]

The Field Rifles Battalion (Feldjägerbataillon) had a different uniform. The officers and cadets wore the same uniform as the Tyrolean Jägerbataillon, while the ordinary soldiers wore grey uniforms with green facings and the red-brown fez. The žandamerijskom corps wore the standard jäger hat with black feathers.

In 1908 "pike-grey" (light blue-grey) uniforms were introduced for field service and ordinary duty wear. The pale blue tunics and breeches were retained for parade and off-duty wear until the outbreak of war in 1914. In 1910 a pike-grey fez was adopted, although the red-brown model was retained for full dress and walking out.[13]

During the early months of World War I the pike-grey uniform proved too conspicuous against the dark forest backgrounds common on the Eastern Front. Greenish tinged "field-grey" uniforms of a similar shade to that of the Imperial German Army were accordingly issued. For reasons of economy the distinctive knee-breeches of the Bosnian regiments were replaced with the universal model of the Austro-Hungarian infantry.[14] In practice, supply shortages led to mixtures of field-grey, pike-grey and even peacetime blue clothing being worn for the remainder of the war. The fez remained in general use.

Weaponry

For most of its existence the Bosnian units were equipped with the Austrian Gewehr Mannlicher M 1890 rifle. The religious requirements of Muslim soldiers were meticulously observed and respected. Junior officers and NCOs came up the ranks during the first phase of training. Within the German-speaking Habsburg army these five units were considered as an elite, warranting a special separate numbering system (within the line infantry).

Legacy

In 1895 Eduard Wagnes wrote the "Die Bosniaken Kommen" march to honour the k.u.k. Bosnian soldiers, the second Infantry Regiment in particular.

Many Bosnian soldiers from the Second Regiment were killed over 1916 and 1917 in fighting in north Italy during World War I and were subsequently buried in the small village of Lebring-Sankt Margarethen, near Graz, Austria. Since 1917 locals have held a modest memorial service to mark the anniversary of the Battle of Monte Meletti in South Tyrol, only interrupted briefly during the Nazi period. Currently there is a Memorial plaque and a street named "Zweierbosniakengasse" ("Second Bosniak Street") in Graz. The Italians and the Austrians have also erected a Memorial plaque to the role of the Bosnian soldiers in the biggest Italian military defeat of the war. An impassable ridge defended by Bosnian soldiers four kilometers north of Gorizia is now called the "Passo del Bosniaco" (Pass of the Bosniak). In honour of the Fourth regiment a monument has been erected on the eastern slope of Rombon mountain in Slovenia. Two Bosnian soldiers wearing fez are carved on granite, which takes into account the Rombon. The monument was made by Ladislav Kofranek, a sculptor from Prague.

In 1929 the Army History Museum in Vienna erected a Memorial Plaque to the Bosnian veterans.

| Cemetery of the 2nd regiment, Bosnian-Herzegovinian Infantry in Lebring-Sankt Margarethen, Austria | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gallery

Notes

References

- ↑ All such informations as of August 1914

- ↑ Neumayer, p. 24.

- 1 2 Malcolm, Noel (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5561-5.

- ↑ Karčić, p . 118.

- ↑ Karčić, p. 119.

- ↑ Neumayer, p. 51.

- ↑ Neumayer, p. 104.

- ↑ Neumayer p. 137.

- ↑ Neumayer p. 135.

- ↑ Tomes, Jason. King Zog of Albania: Europe's Self-Made Muslim Monarch, 2003 (ISBN 0-7509-3077-2) , page.33.

- ↑ Lepre, George (2000). Himmler's Bosnian Division: The Waffen-SS Handschar Division 1943-1945. Schiffer Publishing. p. 118. ISBN 0-7643-0134-9.

- ↑ Neumayer p. 262.

- ↑ Neumayer p. 199.

- ↑ Neumayer p 204.

Sources

- Neumayer, Christoh. The Emperor's Bosniaks. ISBN 978-3-902526-17-5.

- Karčić, Fikret (1999). The Bosniaks and the Challenges of Modernity: Late Ottoman and Hapsburg Times. ISBN 9789958230219.

Further reading

- Noel Malcolm, Bosnia: A Short History, 1994

- Johann C. Allmayer-Beck, Erich Lessing: Die K.u.k. Armee. 1848-1918. Verlag Bertelsmann, München 1974, ISBN 3-570-07287-8

- Stefan Rest: Des Kaisers Rock im ersten Weltkrieg. Verlag Militaria, Wien 2002, ISBN 3-9501642-0-0

- Werner Schachinger, Die Bosniaken kommen! - Elitetruppe in der k.u.k. Armee 1879-1918. Leopold Stocker Verlag, Graz 1994, ISBN 978-3-7020-0574-0

- k.u.k. Kriegsministerium „Dislokation und Einteilung des k.u.k Heeres, der k.u.k. Kriegsmarine, der k.k. Landwehr und der k.u. Landwehr“ in: Seidels kleines Armeeschema - Herausg.: Seidel & Sohn Wien 1914

- Lepre, George (2000). Himmler's Bosnian Division: The Waffen-SS Handschar Division 1943-1945 Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 0-7643-0134-9, page.118.

- Tomes, Jason. King Zog of Albania: Europe's Self-Made Muslim Monarch, 2003 (ISBN 0-7509-3077-2)

- Donia R., Islam under Double Eagle: The Muslims of Bosnia and Hercegovina, 1878-1914

- F. Schmid, Bosnien und Herzegowina unter der Verwaltung Österreich-Ungarns (Leipzig, 1914)

- B. E. Schmitt, The Annexation of Bosnia, 1908–1909 (Cambridge, 1937)

- Adelheid Wölfl, "Mit dem Fes auf dem Kopf für Österreich-Ungarn" in Der Standard (20. Jänner 2014)

- Fabian Bonertz, "Remembering the Bosnian Infantry", University of Regensburg, http://www.uni-regensburg.de/Fakultaeten/phil_Fak_III/Geschichte/istrien/route-log-pod-mangartom.html#infantry