Boston Vigilance Committee

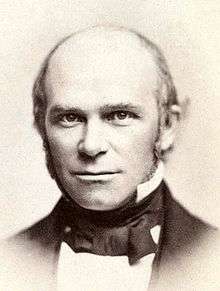

Boston Vigilance Committee was an abolitionist organization formed in Boston, Massachusetts on June 4, 1841 at the Marlboro Chapel, Hall No. 3.[1] with the mission of protecting fugitive slaves from being kidnapped and returned to their Southern owners in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. The organization was led by Theodore Parker, an American Transcendentalist and reforming minister of the Unitarian church. Parker is known to history as a member of the Secret Six, an abolitionist group which supported John Brown.

Definition

A vigilance committee, in the 19th century United States, was a group of private citizens who organized themselves for self-protection. The committees were established in areas where there was no local law enforcement, or where the local government was ineffectual, corrupt, or unpopular. The groups, despite generally held opinions, were not mobs of unorganized individuals bent on revenge of the moment, but usually well-organized, with charters defining their purposes and official membership lists.

Some were public, but many were secret. Secrecy prevented retaliation by lawless or corrupt organizations and also made it difficult for government officials to pursue criminal charges in areas where the government held jurisdiction. Vigilance committees are not unique to the United States and existed into the 20th century.

Fugitive Slave Law

Before the Civil War, Fugitive Slave Laws authorized slave hunters to pursue run-away slaves into non-slave states.[2] All through the North, vigilance committees opposed to slavery provided fugitive slaves protection,[2] food, clothing, and temporary shelter. They also assisted run-aways in using the Underground railroad[2] toward Canada, which did not recognize the Fugitive Slave Act.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was a Federal law which enforced a section of the United States Constitution that required the return of runaway slaves. It sought to force the authorities in free states to return fugitive slaves to their masters.[2]

State's response to the act

Some Northern states passed "personal liberty laws", mandating a jury trial before alleged fugitive slaves could be moved. Otherwise, they feared free blacks (who could vote in ten of the 13 states at the time of the adoption of the Constitution) could be kidnapped into slavery. Other states forbade the use of local jails or the assistance of state officials in the arrest or return of such fugitives. In some cases, juries simply refused to convict individuals who had been indicted under the Federal law. Moreover, locals in some areas actively fought attempts to seize fugitives and return them to the South.

The Missouri State Supreme Court routinely held that transportation of slaves into free states automatically made them free. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), that states did not have to proffer aid in the hunting or recapture of slaves, greatly weakening the law of 1793.

In the response to the weakening of the original fugitive slave act, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 made any Federal marshal or other official who did not arrest an alleged runaway slave liable to a fine of $1,000. Law-enforcement officials everywhere now had a duty to arrest anyone suspected of being a runaway slave on no more evidence than a claimant's sworn testimony of ownership. The suspected slave could not ask for a jury trial or testify on his or her own behalf. In addition, any person aiding a runaway slave by providing food or shelter was subject to six months' imprisonment and a $1,000 fine.[2] Officers who captured a fugitive slave were entitled to a fee for their work.

With this new law, many Northern citizens of the United States felt compromised in their views on slavery. Whereas the Underground Railroad had previously supported fugitive slaves escape from Southern slaveholding states to freedom in Northern states, the Fugitive Slave Law left those who opposed slavery with the immediate choice of either defying what they believed was an unjust law, or breaking with their beliefs.

Founding of the Boston Vigilance Committee

In response to the law, the Boston Vigilance Committee began advocating resistance to the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law through a variety of means. Members contributed funds to send fugitive slaves on to Canada, and for giving shelter and hiding to slaves making their way to Boston. When slaves were captured, the Committee paid for legal fees, and provided money which allowed escaped slaves to purchase necessities.[3]

Shadrach Minkins

Additionally the Committee also carried out more violent resistance. In 1851, members stormed Federal marshals and freed Shadrach Minkins, a slave who escaped from Virginia, and who had been captured in Boston.[4]

Associates of the group included Francis Jackson.[5]

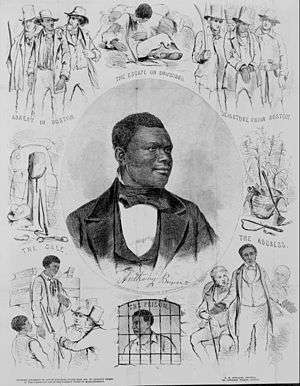

Anthony Burns

The case of escaped slave Anthony Burns fell under this statute. His arrest in Boston, and Judge Edward G. Loring's decision to order him back into slavery in Virginia, outraged abolitionists and many ordinary Bostonians, who were increasingly hostile towards the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Abolitionist planned to free Burns from prison and spirit him to safety were frustrated when President Pierce deployed federal artillery and Marines to take Burns to the ship back to Virginia.

See also

References

- ↑ William Cooper Nell (2002). William Cooper Nell, Nineteenth-Century African American Abolitionist, Historian, Integrationist: Selected Writings from 1832-1874. Black Classic Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-57478-019-2. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fugitive Slave Law. Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Black History: Fugitives". primaryresearch.org. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ↑ The Ordeal of Shadrach Minkins. Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ↑ Life and correspondence of Theodore Parker. 1864

Further reading

- The Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired With John Brown, by Edward Renehan. (1997) (ISBN 1-57003-181-9)

- The Secret Six: John Brown and the Abolitionist Movement, by Otto J. Scott. (1979) (ISBN 0-8129-0777-9)