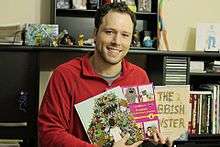

Braam Jordaan

| Braam Jordaan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Johannes Abram Jordaan 1981 Benoni, Johannesburg, South Africa |

| Residence | Cape Town, South Africa |

| Nationality | South African |

| Education | Universal Computer Arts Academy |

| Occupation | Author, filmmaker, animator, advocate |

| Employer | Convo Communications in Manhattan, New York City, Director of International Relations and Development |

| Organization | World Federation of the Deaf, World Federation of the Deaf Youth Section, United Nations, UNICEF Youth Council Member Global Partnership on Children with Disabilities |

| Known for | The Rubbish Monster, director, producer, writer, animation (2006) |

| Website | http://www.braamjordaan.com/ |

Braam Jordaan is a South African filmmaker, animator, and activist. He is an advocate for Sign Language and human rights of Deaf people, and board member of the World Federation of the Deaf Youth Section.[1][2][3][4] In 2009, Jordaan collaborated with the Canadian Cultural Society of the Deaf and Marblemedia on the first children’s animated dictionary of American Sign Language, which allows deaf children to look up words in their own primary language of ASL along with the English counterpart.[1] The dictionary allows both deaf children and their hearing parents to learn sign language together.[5]

Jordaan was interviewed by international news organizations including The Washington Times, BBC, and People magazine about the sign language interpreter scandal during the funeral services of President Nelson Mandela.[5][6][7]

In 2014, Jordaan collaborated with the Camp Mark Seven's first summer of Deaf Film Camp in the making the hit song Happy by Pharrell Williams into an American Sign Language music video.[3][8] The music video made by all 24 camp students was selected as one of NBC News 25 Most Inspirational Stories of the Year and listed as one of People magazine's 2014 Internet Trends.[3][7][9]

Early life and education

Jordaan was born in Benoni, Johannesburg, South Africa during the era of apartheid to a predominantly deaf family that later moved to Cape Town, South Africa.[10] He attended high school at De La Bat School for the Deaf in Worcester.[11] During high school, Jordaan participated in the Law Commission Workshop at The Bastion in Newlands, Cape Town. At the age of 16, he attended the first-ever Deaf Youth Leadership Camp in Durban, led by Wilma Newhoudt-Druchen, which led to Jordaan being elected to attend the National Youth Policy Commission in Midrand in 1998.[12] In 1998, he became a Member of the Council of Learners, and the Chairperson of the council in 2000.[13]

Career

Jordaan's career began at Wicked Pixels, post-production company, creating visual effects and animation for TV commercials, with a client list that included BMW, Rabea Tea, Mitsubishi, Musica, World Wildlife Fund, American Eagle and Yardley.[10]

In 2002, Jordaan won best newcomer and best creative at the Vuka awards by creating a three-dimensional animation advertisement about HIV/Aids awareness.[11] He also created Sipho the Lion, the official mascot of the XVI World Congress of the World Federation of the Deaf.[10] In 2010, Jordaan created visual effects and animation for an award winning short film with Gallaudet University called Gallaudet, which had over 140,000 views.[13] Jordaan created a video montage that stretched 1,500 feet at the DeafNation World Expo in 2012.[14] He also won the DeafNation Inspiration Award for Visual Arts that year.[15]

Deaf education and awareness advocacy

Jordaan became a representative of World Federation of the Deaf, an international organization that represents 70 million deaf people worldwide, and World Federation of the Deaf Youth Section, a youth section under the World Federation of the Deaf.[16] In 2012, during the Hong Kong International Deaf Film Festival, Jordaan appealed to the Hong Kong government for the development of proper sign language curriculum and for the accessibility of sign language interpreters in their nation.[17] In 2014, Jordaan delivered a statement about the right to an education in sign language for deaf youth and children to the Youth with Disabilities of the Seventh Conference of States Parties to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.[18] He also works with the United Nations and is a Youth Council Member of the UNICEF Global Partnership on Children with Disabilities.[19]

#WHccNow campaign

Jordaan launched a social media campaign around the hashtag #WHccNow to advocate for the White House to improve accessibility for Deaf and hard of hearing people from the government.[20] Without closed captions on videos from the White House, Deaf and hard of hearing people are excluded. The hashtag stands for ‘White House closed caption now,’ and it trended on Twitter’s accessibility advocate communities.[21] The White House responded with a State of the Union preview video with open captions posted on social media and the State Department Special Advisor for International Disability Rights, Judith Heumann announced that the White House opened Accessibility Officer position to lead inclusion efforts.

References

- 1 2 McLean, Tom (December 8, 2009). "Animated dictionary for deaf children unveiled". Animation Magazine. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Speaking out: Young voices on NCDs". UNICEF. September 23, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Awford, Jenny (August 27, 2014). "Happy campers: Inspirational deaf summer camp group uses sign language to put a new spin on Pharrell hit". Daily Mail. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ Simon, Natalie (December 11, 2013). "Outrage over sign language interpreter at Madiba Memorial". Yahoo News. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- 1 2 "Transcript of Braam Jordaan Interview". BBC World News. December 19, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ Cheryl K. Chumley (December 11, 2013). "Mandela service sign language interpreter: 'He made up his own signs'". The Washington Times. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- 1 2 Billups, Andrea (December 11, 2013). "Mandela Memorial Deaf interpreter was a fake". People. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ Daily Mail Reporter (April 23, 2013). "Calling Spielberg! Deaf Oscar hopefuls get their big shot at an innovative summer 'Deaf Film Camp'". Daily Mail. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ Serico, Chris (December 25, 2014). "The 25 most inspirational stories of the year". NBC News. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Star profile". This Ability. October 21, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- 1 2 "Capetonian wins TV ad award". News 24 Archives. November 25, 2002. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Lawrence, Sarah (June 4, 2015). "Leading and pushing for change, Braam Jordaan's representation promises great things". SL First Magazine. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- 1 2 Lawrence, Sarah (April 8, 2015). "Braam Jordaan, instrumental Deaf film producer and human rights ambassador". SL First Magazine. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Stunning Exhibition of 2012 DeafNation World Expo". DeafNation. 2010. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "DeafNation 2012 Inspirational Awards". DeafNation. 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "UNICEF Activate Talk - Speaking out: Young voices on non communicable diseases". World Federation of the Deaf Youth Section (WFDYS). September 23, 2014. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ↑ Meigs, Doug (February 27, 2012). "Beyond silent films". China Daily Asia. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ↑ "WFD and WFDYS statement delivered by Braam Jordaan at the panel of Youth with Disabilities of the 7th Conference of States Parties to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 12 June 2014". World Federation of the Deaf. September 23, 2014. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Let's "Beard Up Braam" campaign". News 24. March 10, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ↑ Jabulile S. Ngwenya (December 2, 2015). "People with disabilities have rights". African News Agency. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ Griffin, Emily (December 31, 2015). "#WHCCNOW campaign succeeds in getting closed captions on White House video". 3PlayMedia. Retrieved January 31, 2016.