Clock Tower, Brighton

| Clock Tower | |

|---|---|

|

The Clock Tower, lit up for the festive season. | |

| Location | North Street, Brighton, Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 50°49′25″N 0°08′37″W / 50.8237°N 0.1436°WCoordinates: 50°49′25″N 0°08′37″W / 50.8237°N 0.1436°W |

| Founded | 1887 |

| Built | 1888 |

| Built for | James Willing |

| Architect | John Johnson |

| Architectural style(s) | Classical |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name: Clock Tower and Attached Railings | |

| Designated | 26 August 1999 |

| Reference no. | 1380624 |

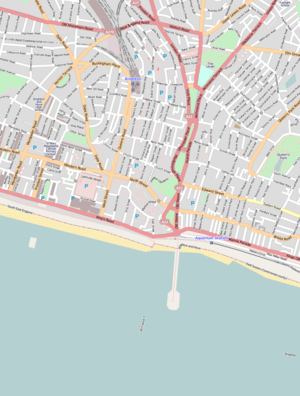

Location within central Brighton | |

The Clock Tower (sometimes called the Jubilee Clock Tower) is a free-standing clock tower in the centre of Brighton, part of the English city of Brighton and Hove. Built in 1888 in commemoration of Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee, the distinctive structure included innovative structural features and became a landmark in the popular and fashionable seaside resort.[1] The city's residents "retain a nostalgic affection" for it,[2] even though opinion is sharply divided as to the tower's architectural merit. English Heritage has listed the clock tower at Grade II for its architectural and historical importance.

History

The small fishing village of Brighthelmston was transformed into a fashionable seaside resort and thriving commercial centre after local doctor Richard Russell's treatise explaining the health-giving effects of drinking and bathing in seawater became a fad in the late 18th century.[3][4] Royal patronage ensued—the Prince Regent (later King George IV) moved into a farmhouse which became the lavish Royal Pavilion—and speculative residential and commercial development, encouraged by transport improvements, attracted large numbers of day-trippers, holidaymakers and new residents throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.[5][6]

By the 1780s, North Street had become established as an important shopping street, and its status as the commercial heart of Brighton grew over the next century.[7] It first developed as a route in the 14th century, when it formed the medieval village's northern boundary, and ran from west to east from the end of the main route from London towards the Royal Pavilion and the seafront.[8] West Street, the ancient western boundary of the settlement, ran southwards towards the beach and seafront;[9] and Queen's Road was built straight through a slum area in 1845 to link the recently built railway station directly with the centre of Brighton.[10] The western section of North Street was renamed Western Road in the 1830s to match the rest of that road, which was built as an access route to the high-class Brunswick Town estate but became the town's main shopping street by the 1860s[11] (the remaining section of North Street was lined with offices and banks by this time).[8]

The roads were widened in the second half of the 19th century, and by 1880 the junction of North Street, Western Road, West Street and Queen's Road was a major landmark with a small, old waiting shelter in the middle.[12] The site was ideal for redevelopment, and in 1881 a competition was held for a replacement building. Architects Henry Branch and Thomas Simpson were recorded as the winners, but their plans were never executed and the site stood vacant until 1888.[1]

Queen Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee in 1887, and many towns built Jubilee clock towers to commemorate the occasion. A local advertising contractor, James Willing,[note 1] decided to commission one for Brighton.[7][13][14] He donated £2,000.[7] The town organised an architectural competition which was won by a London-based architect, John Johnson.[1] The tower was completed at the start of 1888 and was unveiled on 20 January 1888 on Willing's 70th birthday.[13]

Local inventor Magnus Volk—responsible for Britain's oldest surviving electric railway, an eccentric sea-based railway line, a pioneering electric car and Brighton's first telephone link—designed a time ball for the clock tower soon after it opened.[2][15] The hydraulically operated copper sphere moved up and down a 16-foot (4.9 m) metal mast every hour, based on electrical signals transmitted from the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. The feature was disabled after a few years because of complaints about the noise it caused.[2][7][13][14]

The tower was the focal point of several bursts of anti-Victorian sentiment in Brighton in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; as such it fulfilled a similar function to the Albert Memorial in London's Kensington Gardens, which was occasionally the scene of similar local and national demonstrations.[13]

The tower is acknowledged as one of Brighton's main landmarks[1] (although its impact has been affected by intrusive street furniture),[14] and it has been described as "the hub of modern Brighton".[2] The "nostalgic affection" felt by the city's population towards the structure, and the difficulty of demolishing or removing it without great expense, have ensured its survival despite demands (occasionally vociferous) for its destruction.[2][13] Criticism by architectural historians has sometimes been intense, although others have praised the tower. Nikolaus Pevsner and Ian Nairn dismissed it as "worthless",[1][16] and it has been likened to "a giant salt-cellar";[14] but its idiosyncratic appeal has prompted descriptions such as "charmingly ugly"[14] and "extremely charming and delightful",[13] and the most recent academic study of the city's architecture acclaimed it as "supremely confident and showy".[1]

The Clock Tower was listed at Grade II by English Heritage on 26 August 1999.[17] This status is given to "nationally important buildings of special interest".[18] As of February 2001, it was one of 1,124 Grade II-listed buildings and structures, and 1,218 listed buildings of all grades, in the city of Brighton and Hove.[19]

Architecture

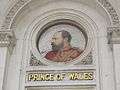

The Clock Tower is a Classical-style structure with Baroque touches.[13][14] It rises to 75 feet (23 m), and the mast for Volk's time ball adds a further 16 feet (4.9 m). The four clock faces have a diameter of 5 feet (1.5 m).[2] James Willing and 1887 are inscribed on the clock faces.[17] The square base is of pink granite, as are the Corinthian columns on each shaft; the rest of the structure is of Portland stone. On each side, the tapering columns rise part way up the shaft and are topped by pediments with open bases, below which is elaborately carved scrollwork and a protuberance designed to resemble the gunwale of a ship. Incised lettering on each ship indicates where they are pointing: clockwise from north, they show to the station, to kemp town, to the sea and to hove.[2][14][17] Below these, each side has an arched recess containing a medallion-style mosaic portrait of a member of the Royal Family. At the corners of the base, there are carved stone statues of female figures.[13][14][17] Above the pediments, the rusticated stone walls are decorated with pilasters, narrow round-headed recesses and a frieze formed by enclosed balusters.[17] Pevsner saw Gothic elements in the design of this section.[16] Above the frieze, an ornate cornice with turrets at each corner[13] is topped by a dome with a copper fish-scale roof, the time ball and a weather-vane topped with James Willing's initials.[17] There had once been public toilets under the structure.[20][21]

-

Portrait of Albert, Prince Consort

-

Portrait of the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII

-

Portrait of the Princess of Wales, later Queen Alexandra

-

Portrait of Queen Victoria

References

Notes

- ↑ Some sources give his name as John Willing.

Sources

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 162.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Carder 1990, §41.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §161.

- ↑ Musgrave 1981, p. 54.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §71.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, pp. 15, 22.

- 1 2 3 4 Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 163.

- 1 2 Carder 1990, §112.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §205.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §139.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §207.

- ↑ Musgrave 1981, p. 294.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Musgrave 1981, p. 295.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Brighton Polytechnic. School of Architecture and Interior Design 1987, p. 54.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §195.

- 1 2 Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 445.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Historic England. "Clock Tower and Attached Railings, North Street (north side), Brighton (Grade II) (1380624)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ↑ "Listed Buildings". English Heritage. 2012. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ "Images of England – Statistics by County (East Sussex)". Images of England. English Heritage. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ Roy, Duncan. "Unofficial public toilets in Brighton and Hove". Scrapper Duncan. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ↑ "Clock Tower: The mechanism". My Brighton and Hove. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

Bibliography

- Antram, Nicholas; Morrice, Richard (2008). Brighton and Hove. Pevsner Architectural Guides. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12661-7.

- Brighton Polytechnic. School of Architecture and Interior Design (1987). A Guide to the Buildings of Brighton. Macclesfield: McMillan Martin. ISBN 1-869865-03-0.

- Carder, Timothy (1990). The Encyclopaedia of Brighton. Lewes: East Sussex County Libraries. ISBN 0-86147-315-9.

- Musgrave, Clifford (1981). Life in Brighton. Rochester: Rochester Press. ISBN 0-571-09285-3.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071028-0.

.jpg)

.jpg)