Buddhism in Pakistan

Buddhism took root in Pakistan some 2,300 years ago under the Mauryan king Ashoka, whom Nehru once called “greater than any king or emperor.”[1] Buddhism has a long history in the Pakistan region — over time being part of areas within Bactria, the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the Kushan Empire; Ancient India with the Maurya Empire of Ashoka, the Pala Empire; the Punjab region, and Indus River Valley cultures — areas now within the present day nation of Pakistan. Buddhist scholar Kumāralabdha (童受) of Taxila was comparable to Aryadeva, Aśvaghoṣa and Nagarjuna. In 2012 the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) indicated that the contemporary Buddhist population of Pakistan was minuscule with 1,492 adult holders of national identity cards (CNICs). The total population of Buddhists is therefore unlikely to be more than a few thousand.[2]

The only functional Buddhist temple in Pakistan is in the Diplomatic Enclave at Islamabad, used by Buddhist diplomats from countries like Sri Lanka.[3]

Buddhism in antiquity

Regions

Gandhara

The majority of people in Gandhara, present day Southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, were Buddhist. Gandhara was largely Mahayana Buddhist, but also a stronghold of Vajrayana Buddhism. The Swat Valley, known in antiquity as Uddiyana, was a kingdom tributary to Gandhara. There are many archaeological sites from the Buddhist era in Swat.

Uddiyana

The Buddhist sage Padmasambhava is said to have been born in a village near the present day town of Chakdara in Lower Dir District, which was then a part of Oddiyana. Padmasambhava is known as Guru Rinpoche in Tibetan and it is he who introduced Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet.

Punjab region

Buddhism was practiced in the Punjab region, with many Buddhist monastery and stupa sites in the Taxila World Heritage Site locale. It was also practiced in the Sindh regions.

Islam and Hinduism

Gandhara remained a largely Hindu-Buddhist land until around 10th century CE, when Sultan Mahmud conquered the region and introduced Islam. There was settlement of Muslims and the emigration of Hindu-Buddhists.[4]

Most Buddhists in Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh were in process of converting to Hinduism from 600 CE onwards. Many Buddhists converted to Islam.. Buddhism was practiced by the majority of the population of Sindh up to the Arab conquest by the Umayyad Caliphate in 710 CE. These regions became predominantly Muslim during the rule of Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughal Empire due to the missionary Sufi saints whose dargahs (shrines) dot the landscape of Pakistan and the rest of South Asia.

Taliban destruction of Buddhist relics

The Swat Valley in Pakistan has many Buddhist carvings and stupas, and Jehanabad contains a Seated Buddha statue.[5] Kushan era Buddhist stupas and statues in Swat valley were demolished by the Taliban and after two attempts by the Taliban, the Jehanabad Buddha's face was dynamited.[6][7][8] Only the Bamiyan Buddhas were larger than the carved giant Buddha statue in Swat near Mangalore which the Taliban attacked.[9] The government did nothing to safeguard the statue after the initial attempt at destroying it, which did not cause permanent harm, but when the second attack took place on the statue the feet, shoulders, and face were demolished.[10] Islamists such as the Taliban and looters destroyed much of Pakistan's Buddhist artifacts left over from the Buddhist Gandhara civilization, especially in Swat Valley.[11] The Taliban deliberately targeted Gandhara Buddhist relics for destruction.[12] The Christian Archbishop of Lahore Lawrence John Saldanha wrote a letter to Pakistan's government denouncing the Taliban activities in Swat Valley including their destruction of Buddha statues and their attacks on Christians, Sikhs, and Hindus.[13] Gandhara Buddhist artifacts were also looted by smugglers.[14]

Pakistan Buddhist tourism

In March 2013, a group of around 20 Buddhist monks from South Korea made the journey to the monastery of Takht-e-Bahi, 170 kilometres (106 miles) from Islamabad. The monks defied appeals from Seoul to abandon their trip for safety reasons and were guarded by Pakistani security forces on their visit to the monastery, built of ochre-coloured stone and nestled on a mountainside. From around 1,000 years BC until the seventh century AD, northern Pakistan and parts of modern Afghanistan formed the Gandhara kingdom, where Greek and Buddhist customs mixed to create what became the Mahayana strand of the religion. The monk Marananta set out from what is now northwest Pakistan to cross China and spread Buddhism on the Korean peninsula during the fourth century. The authorities are even planning package tours for visitors from China, Japan, Singapore and South Korea, including trips to the Buddhist sites at Takht-e-Bahi, Swat, Peshawar and Taxila, near Islamabad.[15]

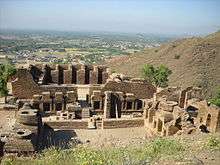

Takht-i-Bahi

Takht means “throne” and bahi, “water” or “spring” in Persian/Urdu. The monastic complex was called Takht-i-Bahi because it was built atop a hill and also adjacent to a stream. Located 80 kilometers from Peshawar and 16 kilometers Northwest of the city of Mardan, Takht-I-Bahi was unearthed in early 20th century and in 1980 it was included in the UNESCO World Heritage list as the largest Buddhist remains in Gandhara, along with the Sahr-i-Bahlol urban remains that date back to the same period, located about a kilometer south.[16]

Takht-i-Bahi is a great source of information on Buddhism and the way of life people here used to follow. The village is built on the ruins of the ancient town, the foundation walls of which are still in a tolerably good formation. As a proof that it was in the past occupied by the Buddhists and Hindu races, coins of those periods are still found at the site. the monks constructed it for their convenience. Spring water was supplied to them on hill tops; living quarters were fitted with ventilators and alcoves for oil lamps were made in the walls. From the description of Song Yun, a Chinese pilgrim, it appears that it was on one of the four great cities lying along the important commercial route to India. It was a well-fortified town with four gates outside the northern one, on the mound known as Chajaka Dehri which was a magnificent temple containing beautiful stone images covered in gold leaves. Not far from the rocky defile of Khaperdra, Ashoka built the eastern gate of the town outside of which existed a stupa and a sangharama. Excavations of the site unearthed at Takht-i-Bahi have revealed architectural features that include: the court of many stupas, the monastery, the main stupa, the assembly hall, the low-level chambers, the courtyard, the court of three stupas, the wall of colossi and the secular building. In 1871, Sergeant Wilcher found innumerable sculptures at Takht-i-Bahi. Some depicted stories from the life of Buddha, while others more devotional in nature included the Buddha and Bodhisattva. The Court of Stupas is surrounded on three sides by open alcoves or chapels. The excavators were of the view that these alcoves originally contained single plaster statues of the Buddha either sitting or standing, dedicated in memory of holy men or donated by rich pilgrims. The monastery on the north side was probably a double-storied structure consisting of an open court, ringed with cells, kitchens and a refectory.[17]

Taxila

The modern town of Taxila is 35 km from Islamabad. Most of the archaeological sites of Taxila (600 BC to 500 AD) are located around Taxila Museum. For over one thousand years, Taxila remained famous as a centre of learning Gandhara art of sculpture, architecture, education and Buddhism in the days of Buddhist glory.[18] There are over 50 archaeological sites scattered in a radius of 30 km around Taxila. Some of the most important sites are: Dhamarajika Stupa and Monastery (300 BC - 200 AD), Bhir Mound (600-200 BC), Sirkap (200 BC - 600 AD), Jandial Temple (c.250 BC) and Jaulian Monastery (200 - 600 AD).[19]

A museum comprising various sections with rich archaeological finds of Taxila, arranged in chronological order and properly labeled, has been established close to the site. It is one of the best and well-maintained site museums of Pakistan. The museum's opening hours in the summer are from 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. with a two-hour break, and from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. without a break, in the winter. The museum remains closed on the first Monday of every month and on Muslim religious holidays. The entrance fee costs Rs.4 per person to visit the museum and Rs.4 per person for the archaeological sites. PTDC has a Tourist Information Centre and a motel with seven rooms and a restaurant, just opposite the museum. There is a youth hostel nearby, offering accommodation for members of International Youth Hostels Federation (IYHF).[20]

Mingora

Mingora, 3 km away from Saidu Sharif, has yielded magnificent pieces of Buddhist sculpture and the ruins of a great stupa. Other beauty spots worth visiting are: Marghzar, 13 km. from Saidu Sharif, famous for its "Sufed Mahal", the white marble palace of the former Wali (ruler) of Swat; Kabal, 16 km. from Saidu Sharif, with its excellent golf course; Madyan, 55 km. from Saidu Sharif, Bahrain, Miandam and Kalam.[21]

Swat

The Lush-green valley of Swat District—with its rushing torrents, icy-cold lakes, fruit-laden orchards and flower-decked slopes—is ideal for holiday-makers intent on relaxation. It also has a rich historical past: "Udayana" (the "Garden") of the ancient Hindu epics; "the land of enthralling beauty", where Alexander of Macedonia fought and won some of his major battles before crossing over to the plains of Pakistan, and "the valley of the hanging chains" described by the famous Chinese pilgrim-chroniclers, Huain Tsang and Fa-Hian in the fifth and sixth centuries. Swat was once a cradle for major strands of Buddhism, where 1,400 monasteries flourished: Little Vehicle, Great Vehicle and the Esoteric sects. It was the home of the famous Gandhara School of Sculpture which was an expression of Graeco-Roman form in the local Buddhist tradition.[22]

However, the ruins of great Buddhist stupas, monasteries and statues are found all over Swat.[23]

See also

- Tridev Roy, Pakistani Buddhist politician and leader

- History of Buddhism

- Buddhism in Afghanistan

- History of Pakistan

- Index: Buddhism by country

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buddhism in Pakistan. |

References

- ↑ "Buddhism In Pakistan". http://pakteahouse.net. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Over 35,000 Buddhists, Baha'is call Pakistan home". Tribune.

- ↑ Vesak Festival in Islamabad

- ↑ Ousel, M. (1997). Ancient india and indian civilization. Routledge.

- ↑ http://factsanddetails.com/asian/cat62/sub406/item2566.html

- ↑ Malala Yousafzai (8 October 2013). I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban. Little, Brown. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-316-32241-6.

- ↑ Wijewardena, W.A. (17 February 2014). "'I am Malala': But then, we all are Malalas, aren't we?". Daily FT.

- ↑ Wijewardena, W.A (17 February 2014). "'I am Malala': But Then, We All Are Malalas, Aren't We?". Colombo Telegraph.

- ↑ "Attack on giant Pakistan Buddha". BBC NEWS. 12 September 2007.

- ↑ "Another attack on the giant Buddha of Swat". AsiaNews.it. 10 November 2007.

- ↑ "Taliban and traffickers destroying Pakistan's Buddhist heritage". AsiaNews.it. 22 October 2012.

- ↑ "Taliban trying to destroy Buddhist art from the Gandhara period". AsiaNews.it. 27 November 2009.

- ↑ Felix, Qaiser (21 April 2009). "Archbishop of Lahore: Sharia in the Swat Valley is contrary to Pakistan's founding principles". AsiaNews.it.

- ↑ Rizvi, Jaffer (6 July 2012). "Pakistan police foil huge artefact smuggling attempt". BBC News.

- ↑ "Pakistan hopes for Buddhist tourism boost". Dawn News.

- ↑ "Takht Bhai". http://www.findpk.com. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Takht Bhai". http://www.visitpakistanonline.com/travelguides/heritage/takhtBhai.htm. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Taxila". http://www.pakistantoursguide.com/. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Buddhism in Taxila". http://www.findpk.com/Pakistan/html/buddhist_sites.html. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Buddhism in Taxila". http://www.findpk.com/Pakistan/html/buddhist_sites.html. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Buddhism in Mingora". http://www.cybercity-online.net/. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Buddhism in SWAT". http://www.cybercity-online.net. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Buddhism in SWAT". http://www.asia-planet.net/pakistan/region-cities.htm. External link in

|website=(help)