Burgh Muir

The Burgh Muir is the historic term for an extensive area of land lying to the south of Edinburgh city centre, upon which much of the southern part of the city now stands following its gradual spread and more especially its rapid expansion in the late 18th and 19th centuries. The name has been retained today in the partly anglicised form Boroughmuir for a much smaller district within Bruntsfield, vaguely defined by the presence of Boroughmuir High School, and, until 2010, Boroughmuirhead Post Office in its north-west corner. The older form of the name is also retained by a street between Church Hill and Holy Corner in Morningside which recalls the vanished hamlet of Burghmuirhead. The post office has moved from the location it occupied for over a century to nearby Bruntsfield Place, thus losing its association with Boroughmuirhead. Plans for the state secondary school to relocate were approved in June 2012, and, while it is likely to retain its prestigious name, it too may lose its connection with the Boroughmuir location in all but name.

In terms of today's street names, the historic muir (Scots for 'moor') extended from Leven Street, Bruntsfield Place and Morningside Road in the west to Dalkeith Road in the east, and as far south as the Jordan Burn and east to Peffermill, thus covering a total area of approximately five square miles. The names of the historic roads that bounded it were the "Easter Hiegait", corresponding to Dalkeith Road and the "Wester Hiegait" corresponding to Bruntsfield Place and Morningside Road.[1]

The last surviving open space of the former burgh muir is Bruntsfield Links, a public park adjoining the Meadows to the north.

General History

The burgh muir was part of the ancient Forest of Drumselch, used for hunting and described in a 16th-century chronicle as originally an abode of "hartis, hindis, toddis [foxes] and siclike maner of beastis".[2] It was given to the city as common land by David I in the 12th century and cleared of woodland by a decree of James IV in 1508.[3] The open space was used for grazing cattle which would be driven there through the Cowgate (literally, "cow road") from byres within the town walls where the cows were milked.

No record of David I's gift of the burgh muir has survived, many of the burgh records having been lost during the Wars of Independence and when the Earl of Hertford sacked the city in 1544. It is possible that it was given at the same time as the founding of Holyrood Abbey in the 12th century, the abbey charter (c.1143) containing the first mention of Edinburgh as a royal burgh.[4][5]

Three areas of the muir were exempted from the city's jurisdiction, due to having been previously granted under separate Royal Charters: the Grange (church-held farmland) of St. Giles ("Sanct Gilysis Grange"), and the Provostry lands of Whitehouse and Sergeantry lands of Bruntsfield, both held from the Crown by royal officials.

The Grange lands were forfeited in the reign of David II and awarded to Sir Walter de Wardlaw, Bishop of Glasgow, passing to his kin, the Wardlaws, until 1506, and then to the merchant, John Cant, whose family owned them until 1632. Cant donated 18 acres of his land to help establish the Dominican nunnery of St. Catherine of Siena in 1517, intended to provide for widows of some of the nobility slain at Flodden in 1513. This was the last convent established in pre-Reformation Scotland, from which the surrounding area of Sciennes took its name. A small Chapel of St. John the Baptist built c.1512-13 by Sir John Craufurd, a prebendary of the Grange of St. Giles, as a hermitage for vagabonds, was given to the Sisters by him for use as their conventual chapel. It is believed to have stood on the site later occupied by Sciennes Hill House.[6] In 1632, the lands held by the Cants passed to another merchant family, the Dicks (later Dick Lauder), who inhabited Grange House until the 19th century. Increasingly empty and neglected after 1848, the house was demolished in 1936.[7]

The Bruntsfield lands, held originally by the King's Sergeant, Richard Broune (hence Brounisfield, later Bruntsfield), were granted by Robert II to Alan de Lawdre in 1381. The Lauder family sold them to the merchant John Fairlie in 1603, whose family sold them in turn to Sir George Warrender, a Bailie and later Lord Provost of Edinburgh, in 1695. His descendants signed the estate over to Edinburgh Corporation (Council) in the 1930s. The second Bruntsfield House on the site, dating from the time of the Lauders in the 16th century, still stands.[7]

The Whitehouse lands have had a more complex history. Records show that prior to 1449 they were held by a family of the surname Hog before coming into the hands of Lord Chancellor William Crichton in the reign of James II (c.1449). They passed through numerous hands down the centuries, including Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell (1581) and Walter Scott of Buccleuch (1594), until they were increasingly subfeued in the 19th century, the feudal superiors being, from 1890 onwards, two brothers named Reid. One feuar was the Order of Ursulines which established St. Margaret's Convent (now the Gillis Centre) in 1834, the first Catholic institution established in Scotland since the Reformation.[7]

When the Earl of Hertford attacked Edinburgh in 1544 as part of what was later called the 'Rough Wooing' the original Bruntsfield House was burned to the ground, and it is generally assumed that a similar fate befell the Grange and Whitehouse, as one of Hertford's men wrote, "And the nexte mornyge, very erly we began where we lefte, and continued burnyge all that daye and the two dayes nexte ensuing contynually so that neyther within the wawles nor in the suburbes was lefte any one house unbrent..."[8] It is unclear whether the convent at Sciennes suffered.

James IV's Charter of 1508

The land outwith the exempted portions began to be feued in the early 16th century. The Burgh Records record that in 1490 "...all the haill counsale, deikynis [leaders of craft trades], and community consentit to the assedatioun [feuing] of the space of the burrowmuir", but it was not until 1508 that a Royal Charter issued by James IV gave the Council licence to feu, stipulating that "the foresaid lands shall be leased in feu-farm as aforesaid, and their heirs and all dwellers on the same lands be subject to the jurisdiction of our foresaid Burgh, the Provost, Baillies and Officers thereof, present and to come, and that they repair every week with their victuals and other goods to the market of our said Burgh..."[9] A Council enactment of 30 April 1510 obliged the feuars "to build upon the said acres dwelling-houses, malt-barns, and cowbills, and to have servants for the making of malt betwixt [that date?] and Michaelmas 1512; and failing their doing so, to pay £40 to the common works of the town, and also to pay £5 for every acre of three acres of the Common Muir set to them".[10] The Scottish lawyer and antiquarian William Moir Bryce (whose exhaustive researches inform much of this article), writing in an age influenced by the Temperance Movement, thought this a "strange obligation", but it made sense at a time before piped urban water supplies, when beer was the common drink in preference to water drawn from lochs and wells which often proved injurious to health.

Clearing the land

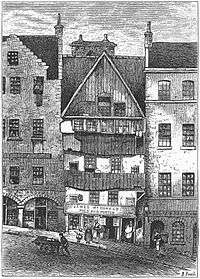

The feuing of the Muir led to the rapid clearing of the remaining woodland on the muir, to dispose of which more easily the Council granted anyone fronting their tenement with wood the liberty of extending the front by seven feet into the street. The resulting timber frontages were followed by wooden fore-stairs which reduced the width of the street even more (until banned by the Council in 1674. A later parliamentary act of 1727 forbade stone-built stairs). According to the 18th-century historian William Maitland, "...the buildings which before had stonern fronts were now converted into wood, and the Burgh into a wooden city".[11] An English visitor William Brereton, commented in 1635 on what he perceived as the hideous effect of these wooden frontages,

Here they usually walk in the middle of the street, which is a fair, spacious, and capacious walk. This street is the glory and beauty of this city: it is the broadest street (except in the Low Countries, where there is a navigable channel in middle of the street) and the longest street I have seen, which begins at the palace, the gate whereof enters straight into the suburbs, and is placed at the lower end of the same. The suburbs make an handsome street; and indeed the street, if the houses, which are very high, and substantially built of stone (some five, some six stories high), were not lined to the outside and faced with boards, it were the most stately and graceful street that ever I saw in my life; but this face of boards, which is towards the street, doth much blemish it, and derogate from glory and beauty; as also the want of fair glass windows, whereof few or none are to be discerned towards the street, which is the more complete, because it is as straight as may be. This lining with boards (wherein are round holes shaped to the proportion of men's heads), and this encroachment into the street about two yards, is a mighty disgrace unto it, for the walls (which were the outside) are stone; so, as if this outside facing of boards were removed, and the houses built uniform all of the same height, it were the most complete street in Christendom.[12]

One of the last timber-fronted houses at the corner of the West Bow and the Lawnmarket was demolished as late as 1878 as part of city improvement measures.

Feuing the land

A record survives from 1511 listing the first 16 feuars who were each given three acres of land on the north side of the burgh loch, divided into a half-acre lot for building and two and a half acres of farmland. This was followed by a further 27 lots granted in 1530, mainly for the South Muir, but including one to the widow of Walter Chapman situated just north of the convent at "Seynis" (Sciennes). Over time most of the South Muir plots came into the possession of the Dick family as owners of the Grange estate. The list of feuars in 1530 also survives, albeit with some gaps.[13]

In 1586, the Council, led by Provost William Little, decided on a further round of feuing by auctioning lots on the Wester Muir and Easter Muir which extended down the southern slope of the muir as far as the Pow Burn (the Dicks of Grange became owners of the Braid estate beyond the burn in 1631). The Wester Muir comprised the lands which developed by a process of sub-leasing, known in Scots Law as subinfeudation, into the districts of Greenhill, Burghmuirhead and Morningside. The Easter Muir comprised the lands which developed likewise into the districts of the Grange, Blackford, Mayfield and Newington.

The feuing of the Grange Estate was sanctioned by a private Act of Parliament in 1825 which allowed its owner, Sir Thomas Dick Lauder, to feu land for the building of residential villas; the first being constructed in 1845.[14]

The Marchmont district, lying directly south of the Meadows, developed on land first feued by the Warrenders of Bruntsfield in 1869.[15]

Military use

The burgh muir was the traditional Edinburgh location for military training and wappenshaws (district inspections of arms) held periodically in accordance with a 1548 Act of Parliament in the reign of James V, which "...decretyt and ordaynit that wapinschawingis be haldin be the lordis and baronys spirituale and temporale four tymis in the yere."[16] It was also where troops were mustered, for example in 1384, and before the Lauder Bridge incident in 1482.[17] A contingent also assembled here to fight the English army before the battle of Flodden in 1513, and again in 1523 and 1542.

In total, the Scottish Army rendezvoused on the muir on at least six occasions prior to invading England.[18] Sir Alexander Lauder of Bruntsfield (along with his two brothers) and his descendant, also Sir Alexander Lauder of Bruntsfield, both died in battle serving the Crown at Flodden and Pinkie respectively; their lands passing to their heirs.[19]

A stone built into the western boundary wall of the former Morningside Parish Church, known as the "Bore Stone" or "Hare Stane" (from Old Scots heir, meaning 'army') is popularly believed to be the stone which held the Royal Standard at the muster for Flodden on the muir in 1513. An accompanying plaque states that it was placed there by the owner of Greenhill House, Sir John Stuart Forbes of Pitsligo, in 1852. The story attached to its origin was established by Sir Walter Scott in his epic poem 'Marmion' (1808) which contains the lines, "The royal banner, floating wide:/The Staff, a pine tree strong and straight:/Pitched deeply in a massive stone/Which still in memory is shown." However, the identification of the stone in Morningside Road with this poetic statement was discredited in an essay published by Henry Paton in 1942. Firstly, the stone has no hole-socket for holding a pole. Secondly, the Royal Treasurer's Accounts for 1513 make it clear that the King left Edinburgh before his standard and other banners had been made ready, and that they were sent after him.[20] The standard must therefore have been first raised at Ellem, near Duns in Berwickshire where the Scottish host assembled before marching into England.[21] According to the historian William Maitland, writing in 1753, the stone was originally situated on the eastern side of the road "almost opposite to the south-eastern corner of the Park-wall of Tipperlin Lone", suggesting it was a boundary marker belonging to the since vanished village of Tipperlin which bordered that side of the road.[22]

Use during the Plague

In times of plague, of which there were several outbreaks in the 16th and 17th centuries, infected victims of "the pest" were sent to the muir as a primitive quarantine measure.[23] Some records suggest that hopeless cases were sent to the chapel at Sciennes (see above), while suspected cases were lodged on the southern slope of the muir in temporary huts clustered round the Chapel of St. Roque, the patron saint of the plague-stricken, built on the Grange c.1503.[24]

Horse or hand-drawn wooden carts conveyed the hapless victims out to the Burgh Muir between the hours of 9.p.m. and 5 a.m. These primitive ambulances were preceded by "Bailies of the Mure", voluntarily recruited men wearing black or grey tunics and St Andrew's Crosses. They carried long staffs used to touch infected materials and rang hand-bells to warn citizens of their dangerous charges. The carts halted at the Burgh or South Loch, now the Meadows. On its south bank were prepared large cauldrons of boiling water in which other Bailies of the Mure, known as "clengeris" [cleansers], carrying long staffs with metal hooks at the tips, attempted to disinfect the victims' clothes.[25]

The Town Council laid down strict regulations to contain the plague. People suspected of infection, because they lived in proximity to others who had died, were taken with their household goods to be "clengit" (cleansed) on the muir. In October 1568, a shoemaker, John Forrest, was appointed as cleanser on the west part of the "Borrow Mure." Another shoemaker and a weaver were made Baillies of the Muir, among whose responsibilities was giving permission to those cleansed to return home. No-one was allowed to visit those suspected of infection on the muir except in the company of these officers. They were issued with similar gowns bearing a white St Andrew's cross on the back and front, and carried a stick with a white cloth on the end "quhairby thai may be knawin quhaireuer thay pas".[26]

In 1585, during another plague outbreak, a "Greitt Fowle Luge" was built on the muir at a location named Purves's Acres. The quarantined "cleansed" were lodged to the west of this building, and newly suspected "foul" persons to the east. There were so many people on the muir that the council ordered that their beer should be brewed thinner. Cleansed persons allowed home were confined to their houses for 15 days. Stealing infected goods was a hanging offence,[27] and a "foul" hangman was employed for the purpose of executing offenders on the muir. It is recorded that Smythie, the "fowle hangman", was chained to his own gibbet on 23 July 1585 for disobedience.[28]

When land in the west muir area was feued in 1597, the council reserved a path at the east end leading to the Braid Burn for use during times of pestilence.[29] Many of the afflicted must have died en route and been buried by the wayside, as evidenced by human remains later unearthed in private gardens.[24]The dead were buried in unmarked burial pits, some of which have left traces in the grounds of the present-day Astley Ainslie Hospital.[30]

As a place of execution

Edinburgh had several execution sites in the past. An area of ground known as "the Gallowgreen" (when its feuing was recorded in 1668)[31] was the site of a gibbet of uncertain date, erected on the eastern edge of the burgh muir. It was deliberately placed to face down the road to Dalkeith, presumably to deter highway robbers. It is known that a horse-thief, also accused of being a "commone gyde to Inglis Thevis" ("a common guide to English thieves"), was hanged "at the galloss of the burrow mure" in 1563; and it is also recorded that two men were hanged for stealing infected clothing during an outbreak of the plague in 1585. In the following year the Town Council ordered the gibbet, described as "foullet and decayand, bayth in the timmer [timber] wark and the wallis", to be replaced close to the same spot (at the present-day junction of East Preston Street and Dalkeith Road) and enclosed by walls of sufficient height "sua tht doggis sal not be abill to cary the cariounis [dead flesh] furth of the samyn"; a statement that implies the practice of hanging the bodies or body parts of malefactors in chains. The new gibbet is described in the Town Council Minutes of 1568 as consisting of two or more stone pillars connected at the top by one or more wooden cross-beams, with the whole structure surrounded by a wall to keep out stray dogs.[32]

Other executions here included the hanging of members of the outlawed McGregor clan, of whom a total of 38 were judicially killed on the spot between 1603 and 1624, as were four 'Gypsies' in 1611, for failing to observe a parliamentary act of 1609 which had banished all "Egyptianis" from the kingdom. They were followed by 11 more Gypsies in 1624, whose womenfolk were initially sentenced to drowning, but eventually ordered to leave Scotland.[33]

The ground at this part of the Muir was also used for the unmarked burials of malefactors. For example, the torso of James Graham, 1st Marquis of Montrose, without his heart (removed from his coffin at the instigation of his niece), was unceremoniously buried in unconsecrated ground after his execution on 21 May 1650. Following the Restoration his remains were disinterred in 1661 and eventually placed in an elaborate tomb in St. Giles.

The diarist John Nicoll recorded the event,

[A guard of honour of four captains with their companies] went out thaireftir to the Burrow mure quhair his corps wer bureyit, and quhair sundry nobles and gentrie his freindis and favorites, both hors and fute wer thair attending; and thair, in presence of sundry nobles, earls, lordis, barones and otheris convenit for the tyme, his graif [grave] was raisit, his body and bones taken out and wrappit up in curious clothes and put in a coffin, quhilk, under a canopy of rich velwet, wer careyit from the Burrow-mure to the Toun of Edinburgh; the nobles barones and gentrie on hors, the Toun of Edinburgh and many thousandis besyde, convoyit these corpis all along, the callouris [colours] fleying, drums towking [beating], trumpettis sounding, muskets cracking and cannones from the Castell roring; all of thame walking on till thai come to the Tolbuith of Edinburgh, frae the quhilke his heid wes very honorablie and with all dew respectis taken doun and put within the coffin under the cannopie with great acclamation and joy; all this tyme the trumpettis, the drumes, cannouns, gunes, the displayit cullouris geving honor to these deid corps. From thence all of thame, both hors and fute, convoyit these deid corps to the Abay Kirk of Halyrudhous quhair he is left inclosit in ane yll [aisle] till forder ordour be by his Majestie and Estaites of Parliament for the solempnitie of his Buriall.[34]

Executions at the gallows on the burgh muir ended in 1675 after the ground had been leased, first to a wright and burgess of Edinburgh in 1668, then, in 1699, to a brewer in the Pleasance. The gibbet continued to be marked on all maps and plans of the district until 1823.[35]

References

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol. X, Edinburgh 1918, contains a court statement made by the Edinburgh magistrates in 1593 which defines its limits in detail: "Begynnand at the west neuke [corner] of the dyke [wall] upoun the south syde of Sanct leonards loneing [lane] qr [where] the grund of the croce stands, and thairfra passand south and south eist as the said dyke gangis be the heids of the airabill landis of Sanctleonards and Preistisfield respectively until it cum to the end of the dyke foresaid, and to the gait that passes to the Priestisfield, Peppermylne, and Nidrie, and fra the south wast syde of the said gait, as ane oyr dyke passes south and south wast, be the sydes of the airable lands of Camroun qll it cum to the south wast neuk of the said dyke, and thairfra doun as the said dyke passes south south eist to the end of the Grene end of the said Commoun Mure by and contigue to the passage and hie street [Dalkeith Road] fra the said burgh of Edr. to the brig end betuix the lone dyke of the said lands of Camroun, and thairfra ascendand the waster lone dyke be the edge of the said commoun mure, and as the said wester lone dyke gannis to the end thairof, quhair it meets at the croce dyke by and upoun the eist syde of the aikers of the said commoun mure pertening to [blank text] and sa linalie be the said dyke qll it cum to the Powburne, and sua up the said Pow burne qll it cum to the loneing that passes to the lands of Newlands pertening to the laird of Braid [bordering the south of the Grange], and thairfra wastwart as the dyke gangis to the south neuk of the dyke situat upone the eister pt of the lands of Tipperlinn, and sua northwart as the said dyke gangis by the yet [gate] of Tipperlinn, and thairfra northwart to the dykes of the corne land heids thairof, passand north as the said dyke gangis to the hie gait that passes by Merchamstoun to the Craighous, and eist be the said gait till it cum to the west dyke of the croft callit the Dow croft [present Albert Terrace], and thairfra sout. to the sout. end of the said dyke and sua nort. eist be the said dyke to the nort. eist neuk thairof, and thairfra nort. wert as the dyke gangis to the nort. west nuk of the same upoun the south syde of the passage that leids fra Edr. by the yett of Merchamstoun, and than begynnand upoun the nort. syde of the said hie passage directlie foiranent [in front of] the nuk of the said dyke be the new yaird dyk laitlie biggit [built] be the laird of Merchamstoun upoun ane pece of the said commoun mure laitlie disponit [transferred in ownership] be the provost baillies and counsall of the said burt. [baronet] for the tyme to him, and sua haldand be the said new dyke and gangand about the samen till it cum to the nort. eist nuk tairof, and thairfra nort. wart and nort. eist be the auld dykes at the heid of the airable lands of Merchimstoun till it cum to the wester gawill [side] of the Coithouses [stone cottages] pertenand to the Laird of Wrytishouses [present Leven Street]."

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918, p.2 quoting Bellenden's Croniklis of Scotland

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918, pp.1-2

- ↑ D Daiches, Edinburgh, London 1978, p.15

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918, "de meo Burgo de Edwinesburg"

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918, pp.96-102

- 1 2 3 W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918

- ↑ British Library Cotton Ms. Augustus I ii 56

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918, p.67

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918, p.67 This extract from the printed Burgh Records, vol.i, p.129 is rendered in modern English, but the original document cannot have used the £-sign for sterling; and is therefore more likely to refer to pounds Scots.

- ↑ W. Maitland, History of Edinburgh, Hamilton, Balfour & Neil, Edinburgh 1753, p.11

- ↑ P Hume Brown (ed.), Early Travellers in Scotland William Maitland (historian), James Thin 1973

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918, pp.71 & 74, where the 1530 list is reprinted from the Extracts from the Town Council Minutes held in the Advocates Library

- ↑ M Cant, Sciennes and the Grange, John Donald 1990, p.2

- ↑ M Cant, Marchmont In Edinburgh, John Donald 1984, p.1

- ↑ Dickinson, Donaldson and Milne (eds.), A Source Book Of Scottish History, vol.ii, Nelson 1953, p.72

- ↑ P Hume Brown, History of Scotland, vol.i, Cambridge 1902, p.277, when Archibald 'Bell-the-Cat' summarily executed the King's favourites by hanging them from the bridge

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918, p.190

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918, pp.21 & 23

- ↑ H M Paton, The Book of the Old Edinburgh Club, vol.xxiv, Edinburgh 1942, pp.79-80, "ane man to byde on the standartis to bring thaim with him in haist that nycht that the kingis grace departit furth of Edinburgh"

- ↑ R L Mackie, King James IV of Scotland, Oliver & Boyd 1958, p.247

- ↑ W Maitland, History of Edinburgh, Hamilton Balfour & Neill 1753, p.507

- ↑ D Daiches, Edinburgh, Hamish Hamilton 1978, p.64

- 1 2 C J Smith, Historic South Edinburgh, vol.1, Edinburgh & London 1978, p.229

- ↑ C J Smith, Historic South Edinburgh, vol.1, Edinburgh & London 1978, pp.228-9 Smith does not identify the precise time in history he is describing in this scene.

- ↑ Marwick, J.D., ed., Extracts from the Burgh Records of Edinburgh, 1557-1571, (1875), pp.250-259, link to pages on British History Online.

- ↑ Marwick, J.D., ed., Extracts from the Burgh Records of Edinburgh, 1573-1589, (1882), pp.430-7; see p.422, 1 June 1585; pp.430-1, 8 July 1585; p.432-3, 23 July 1585 "that na maner of persoun that salhappin pas be the caldrone abstract ony of thair guddis, vnder the pane of deid"

- ↑ Marwick, J.D., ed., Extracts from the Burgh Records of Edinburgh, 1573-1589, (1882), pp.430-7; see p.422, 1 June 1585; pp.430-1, 8 July 1585; p.432-3, 23 July 1585

- ↑ Wood, Marguerite, ed., Extracts from the Records of the Burgh of Edinburgh, 1589-1603, (1927), p.209, The name here may not in fact refer to the present Braid Burn, as this was also another name for the Pow Burn (see Jordan Burn) which was the boundary of both the city and the muir. The path is described as belonging to the lands of Herbert Maxwell. A narrow lane runs north-south through the Grange area today, and, while no direct evidence exists, may follow the line of an older path such as the one mentioned here. It appears on a map of 1766 as Kirk Road, leading to the West Kirk (St. Cuthbert's) and is currently named Lovers Loan. Stuart Harris observes in his 'Place Names of Edinburgh' (1996) that the pairing Kirk/Lovers Loan occurs frequently in Scotland "since dawn-to-dusk working hours six days a week made the long Sunday walks to and from the kirk an important courting occasion".

- ↑ C J Smith, Historic South Edinburgh, vol.1, Edinburgh & London 1978, p.228-9

- ↑ S Harris, The Place Names Of Edinburgh, London 1996 describes this as "a wedge-shaped outshot of the Burgh Muir" which extended from its base about 150 yards along the north side of today's East Preston Street "tapering to a point about 400 yards further north" at today's Spittalfield Crescent.

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol.x, Edinburgh 1918, pp.85-6

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol x, Edinburgh 1918, pp.87ff.

- ↑ John Nicoll, A Diary Of Public Transactions And Other Occurrences, chiefly in Scotland, from January, 1650, to June, 1667, Bannatyne Club 1836

- ↑ W Moir Bryce, The Book Of The Old Edinburgh Club, vol x, Edinburgh 1918, p.96

See also

Coordinates: 55°56′N 3°11′W / 55.933°N 3.183°W