Butterfield Overland Mail

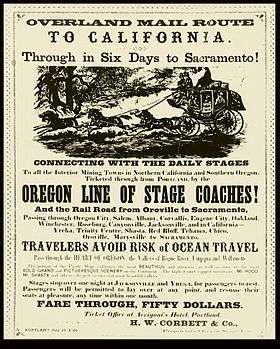

The Butterfield Overland Mail Trail [1] was a stagecoach service in the United States, operating from 1857 to 1861. It carried passengers and U.S. Mail from two eastern termini, Memphis, Tennessee and St. Louis, Missouri to San Francisco, California. The routes from each eastern terminus met at Fort Smith, Arkansas, and then continued through Indian Territory, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Baja California, and California ending in San Francisco.[2] On March 3, 1857, Congress under James Buchanan authorized the U.S. postmaster general, Aaron Brown, to contract for delivery of the U.S. mail from Saint Louis to San Francisco. Prior to this, U.S. Mail bound for the Far West had been transported by ship across the Gulf of Mexico to Panama, where it was freighted across the isthmus to the Pacific, then taken by ship for points in California.[3]

Origins

Through the 1840s and 1850s there was a desire for better communication between the east and west coasts of the US. Though there were several proposals for railroads connecting the two coasts, a more immediate realization was an overland mail route across the west. Congress authorized the Postmaster General to contract for mail service from Missouri to California to facilitate settlement in the west.[4] The Post Office Department advertised for bids for an overland mail service on April 20, 1857. Bidders were to propose routes from the Mississippi River westward.[5]

John W. Butterfield and his associates William B. Dinsmore, William G. Fargo, James V. P. Gardner, Marcus L. Kinyon, Alexander Holland, and Hamilton Spencer created a proposal for a southern route from St. Louis to California. The Post Office Department received nine bids. The Postmaster General, Brown, was from Tennessee and favored a southern route. Although none of the bidders had provided for the route, the Postmaster General advocated a southerly route,[5] known as the Oxbow Route, with the idea that it could remain in operation during the Winter.[3]

"from St. Louis, Missouri, and from Memphis Tennessee, converging at Little Rock, Arkansas; thence, via Preston, Texas, or as nearly so as may be found advisable, to the best point of crossing the Rio Grande, above El Paso and not far from Fort Fillmore; thence along the new road being opened and constructed under direction of the Secretary of the Interior, to Fort Yuma, California; thence, through the best passes and along the best valleys for safe and expeditious staging, to San Francisco." [6]

This route was 600 miles (970 km) longer than the central and northern routes through Denver, Colorado and Salt Lake City, Utah, but was snow free. The bid and route was awarded to Butterfield and his associates, for semi-weekly mail at $600,000 per year.[5] At that time it was the largest land-mail contract ever awarded in the US.

Butterfield Overland Mail Route

The contract with the U.S. Post Office, which went into effect on September 16, 1858, identified the route and divided it into eastern and western divisions. Franklin, Texas later to be named El Paso was the dividing point and these two were subdivided into minor divisions, five in the East and four in the West. These minor divisions were numbered west to east from San Francisco, each under the direction of a superintendent.[3]

San Francisco to St. Louis

Division[7] Route Miles Hours Division 1 San Francisco to Los Angeles 462 80 Division 2 Los Angeles to Fort Yuma 282 72.20 Division 3 Fort Yuma to Tucson 280 71.45 Division 4 Tucson to Franklin 360 82 Division 5 Franklin[8] to Fort Chadbourne 458 126.30 Division 6 Fort Chadbourne to Colbert's Ferry 282½ 65.25 Division 7 Colbert's Ferry to Fort Smith 192 38 Division 8 Fort Smith to Tipton 318½ 48.55 Division 9 Tipton to St. Louis by railroad 160 11.40 Totals 2,795 596.35

San Francisco to Memphis

As noted above, the route from San Francisco to Fort Smith was the same for both routes. Travel time from Fort Smith to Memphis was about the same as to St. Louis. Management of the route from Fort Smith to Memphis was included in Division 8. However, because of the untamed nature of the Mississippi River and its Arkansas tributaries in those years, the southern route necessarily utilized various alternative routes and methods of travel. At that time, there was no Mississippi River bridge at Memphis, and the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad ran from Hopefield near present-day West Memphis, Arkansas only to a point 12 miles east of Madison, Arkansas on the St. Francis River. From there the route headed overland by stagecoach. When the Arkansas River was high enough, the mail could instead travel from Memphis by steamboat down the Mississippi to the mouth of the Arkansas River, navigate up that river to Little Rock, and on from there by stagecoach. When the Arkansas was too low for steamboat traffic, the Butterfield could take the White River to Clarendon, Arkansas or Des Arc, Arkansas before switching to the stagecoaches. Sometimes the entire route across eastern Arkansas would be by stage.[9]

Operation

issued by the U.S. Post Office,

100th Anniversary, October 10, 1958

The Butterfield Overland Mail Company held the U.S. Mail contract from September 15, 1857 on a six-year contract.[5] On that date stages departed from St. Louis and San Francisco for the first time. The stage from San Francisco arrived in St. Louis 23 days and four hours later with the mail and six passengers.[5] The scheduled time between the two points was 25 days.[5]

The Overland Mail made two trips a week over a period of two and a half years. Each Monday and Thursday morning the stagecoach would leave Tipton and San Francisco on their cross continent, carrying passengers, freight and up to 12,000 letters. The western fare one-way from Memphis or St. Louis to the Golden Gate was $200, with most stages arriving at their final destination 22 days later.[5] The Butterfield Overland Stage Company had more than 800 people in its employ, had 139 relay stations, 1800 head of stock and 250 Concord Stagecoaches in service at one time.[10]

During the 1860s there were few routes westward and the Overland Stagecoach Route was one of the primary routes and had to be kept open for settlers, miners and businessmen traveling west. Because the Overland Stagecoach route was being harassed by bandits and Indians, Lincoln's War Department responded by assigning a detachment from the 9th Kansas Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William O. Collins from Fort Laramie in the Wyoming Territory. Collins' detachment guarded the route between Independence, Missouri and Sacramento, California.[11]

With the American Civil War looming, the competing Pony Express was formed in 1860 to deliver mail faster and on a central/northern route away from the volatile southern route. The Pony Express was to succeed in delivering the mail in 10 days, but failed to win the mail contract.

In March 1860, the Overland Stage Company was taken over because of the debt owed to Wells Fargo and as a result John Butterfield was forced out of the business. Butterfield's assets as well as those of the Pony Express were to wind up with the Wells Fargo partners.[10]

A correspondent for the New York Herald, Waterman L. Ormsby, remarked after his 2,812-mile (4,525 km) trek through the western US to San Francisco on a Butterfield Stagecoach thus: "Had I not just come out over the route, I would be perfectly willing to go back, but I now know what Hell is like. I've just had 24 days of it."[2] Ormsby was the only passenger on the first East-West run of the Butterfield Stage who journeyed the entire distance of the mail route. He sent periodic dispatches to the paper describing his journey, including the pickup of passengers outside the Lawrence Livery Stables.[12]

Employing over 800 at its peak, it used 250 Concord Stagecoaches and 1800 head of stock, horses and mules and 139 relay stations or frontier forts in its heyday. The last Oxbow Route run was made March 21, 1861 at the time of the outbreak of the Civil War. The Civil War started on April 12, 1861.[10]

Route discontinued

In March 1861, before the American Civil War had actually begun at Fort Sumter, the US Government formally revoked the contract of the Butterfield Overland Stagecoach Company in anticipation of the coming conflict.[13] An Act of Congress, approved March 2, 1861, discontinued this route and service ceased June 30, 1861. On the same date the central route from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Placerville, California, went into effect. This new route was called the Central Overland California Route.[14]

Under the Confederate States of America, the Butterfield route between Texas and Southern California was operated as part of the Overland Mail Corporation route with limited success from 1861 until early 1862 by George Henry Giddings.[15] Wells Fargo continued its stagecoach runs to mining camps in more northern locations until the coming of the US Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. At least four battles of the American Civil War occurred at or near Butterfield mail posts, the Battle of Stanwix Station, the Battle of Picacho Pass, Second Battle of Mesilla and the Battle of Pea Ridge. Three clashes between the Apache and Confederate or Union forces in the Apache Wars occurred on the route, First Battle of Dragoon Springs, Second Battle of Dragoon Springs, and the Battle of Apache Pass. Confederates attempted to keep the stations from Tucson to Mesilla open while they destroyed the stations from Tucson to Yuma which were used to supply the Union army as it advanced through Traditional Arizona. The burning of the Stanwix Station and others led to a significant delay to the Union advance, postponing the Fall of Tucson, Arizona's western Confederate capital, which housed one of two territorial courts; the other court was in Mesilla. All said engagements happened in the Confederate Arizona and Arkansas sectors of the mail route.

Modern remnants

There are surviving Stage stations at Oak Grove and the most famous is near Warner Springs, California in San Diego County, California.[16] It and the property of Warner's Ranch 20 miles (32 km) away, where the ranch house was used as a station, were declared to be National Historic Landmarks in 1961. Warner's Ranch was the Butterfield Station and a stop for emigrant travelers to the West from 1849–1861, and has two original adobe buildings on the 221-acre (0.89 km2) property. The 1857 ranch house sometimes housed travelers.

The Elkhorn Tavern in the Pea Ridge National Military Park was another destination along the route that was rebuilt after the Civil War. It is on one of the last sections of the trail that still exists—Old Wire Road through Avoca, Rogers and Springdale, Arkansas. Also in Arkansas is the town of Pottsville, which was built around Pott's Inn. Pott's Inn was finished in 1859 and was a popular stop along the route. It survives as a museum owned by the Pope County Historic Society.

When it was first established, the route proceeded due east from Franklin, Texas, toward the Hueco Tanks;[17] the remains of a stagecoach stop are still visible at the Hueco Tanks State Historic Site.

The summit of Guadalupe Peak in Guadalupe Mountains National Park features a stainless steel pyramid erected in 1958 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Butterfield Overland Mail, which passed south of the mountain.

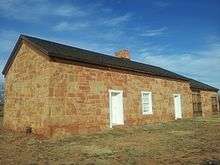

Fort Chadbourne reconstructed stage station.

Fort Chadbourne reconstructed stage station. Fort Chadbourne museum.

Fort Chadbourne museum. Fort Belknap (Texas) Historical Marker.

Fort Belknap (Texas) Historical Marker.- Guadalupe Peak summit, with a pyramid commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Butterfield Overland Mail.

Proposed Butterfield Overland Trail National Historic Trail

On March 30, 2009, President Barack Obama signed Congressional legislation (Sec. 7209 of P.L. 111-11) to conduct a study of designating the trail a National Historic Trail. The United States National Park Service is conducting meetings in affected communities and doing Special Resource Study/Environmental Assessment to determine whether it should become a trail and what the route should be.[18]

In popular culture

A Butterfield Overland stagecoach is featured in the 2015 western film The Hateful Eight.

See also

- San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line

- Butterfield Overland Mail in California

- Butterfield Overland Mail in New Mexico Territory

- Butterfield Overland Mail in Texas

- Butterfield Overland Mail in Indian Territory

- Butterfield Overland Mail in Arkansas and Missouri

- Butterfield Overland Despatch, an unrelated company

- Pony Express

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Confederate States

- Stockton - Los Angeles Road

- Apache Pass Station

References

- ↑ Also known as the Oxbow Route, the Butterfield Overland Stage, or the Butterfield Stage

- 1 2 Waterman L. Ormsby, Lyle H. Wright, Josephine M. Bynum, The Butterfield Overland Mail: Only Through Passenger on the First Westbound Stage. Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, 2007. pp. viii, 167, 173.

- 1 2 3 "Butterfield Stagecoach Overland Mail Co.". Knol. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ↑ "Butterfield Overland Mail Company". Bridgeport, Texas Historical Society. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hafen, Leroy; David Dary (2004). The Overland Mail, 1849-1969: Promoter of Settlement Precursor of Railroads. Norman, Oklahoma, United States of America: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-8061-3600-4.

- ↑ Brown, Aaron (1857). "Postmaster-General's Report".

- ↑ Wright, "Historic Places-Appendix A", p. 821

- ↑ Richardson, "Butterfield Overland Mail": "As of 1858 the route extended from San Francisco to Los Angeles, thence by Fort Yuma, California, and Tucson, Arizona, to Franklin, Texas (present El Paso)."

- ↑ The Butterfield Overland Mail Route Lucian Wood Road Segment. Archived February 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. History & Architecture: Arkansas Historic Preservation Program.

- 1 2 3 "John Butterfield Father of the Butterfield Overland Mail". DesertUSA. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ↑ "Panning for history along Cache la Poudre River". Moultrie News, Charleston SC. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ↑ "Waterman Lilly Ormsby 1834 - 1919". Ormsby.org. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ↑ "THE FORGOTTEN LEGACY A Short History of the Confederate Territory of Arizona, by Robert Perkins". Sons of Confederate Veterans, Phoenix, Arizona. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ↑ Root, The Overland Stage to California, p. 42: "The stock, coaches, etc., on the southern route were pulled off, and accordingly moved north, and, by act of Congress, on July 1, 1861, the route between St. Joseph and Placerville, having been duly equipped for a daily line, went into operation. It took about three months to make the transfer of stages and stock, and to build a number of new stations, secure hay and grain, and get everything in readiness for operating a six-times-a-week mail line. The new line was designated by the post-office department as the Central Overland California Route."

- ↑ Basil C. Pearce, The Jackass Mail—San Antonio and San Diego Mail Line, The Journal of San Diego History, San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, Spring 1969, Volume 15, Number 2

- ↑ Patricia Heintzelman and Charles Snell (1975) National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Oak Grove Butterfield Station, National Park Service, accessed 18 November 2009

- ↑ Butterfield Overland Mail from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ↑ http://parkplanning.nps.gov/projectHome.cfm?projectID=33568

Bibliography

- Richardson, Rupert N. Butterfield Overland Mail from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- Root, Frank. The Overland Stage to California. Topeka, Kansas: W.Y. Morgan, 1901.

- Wright, Muriel H. "Historic Places on the Old Stage Line from Fort Smith to Red River-Appendix A", Chronicles of Oklahoma 11:2 (June 1933) 821-822 (accessed August 16, 2006).

- Hafen, L. R. R. (2004). The overland mail, 1849-1869: promoter of settlement precursor of railroads. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Butterfield, J., Fargo, W. G., & Holland, A. (1857). Letter to the postmaster general in relations to the overland mail to California.

- Butterfield, J. W. (1857). Skeleton map of the overland mail route to California. Route adopted by the department traced in green. Route proposed by John Butterfield and others (who were the lowest bidders) in red.

- Overland Mail Company, & Butterfield, J. (1858). Overland Mail Company: through time schedule between St. Louis, Mo., Memphis, Tenn. & San Francisco, Cal. [S.l: The Company?.

- Reed, M., & Pourade, R. F. (1966). The colorful Butterfield Overland Stage. Reproductions in color of 20 paintings by Marjorie Reed from the collection of James S. Copley. Palm Desert, Calif: Best-West Publications.

Further reading

- Swensen, Henry Edward (1911). The overland mail and passenger service.

The overland mail and passenger service. p. 156., E'book

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Butterfield Overland Mail Company. |

- Desert USA.com: John Butterfield + Butterfield Overland Mail

- Over-land.com: Official Millennium Trail—The Overland Trail

- Butterfield Overland Mail Co., Divisions and Stations of the Butterfield Overland Mail Company

- Jcs-group.com: "The Spell of the West—Butterfield Overland Mail"

- 1958 Overland Mail Centennial U.S. commemorative stamp

- The Moultrie News (Charleston, SC): Butterfield history

- Texas Historical Society: Butterfield Overland Mail Company in Bridgeport

- Butterfield Express under the Confederate States of America

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory .