Camp McClellan (Iowa)

| Camp McClellan | |

|---|---|

|

Marker in Lindsay Park | |

| Location | Davenport, Iowa |

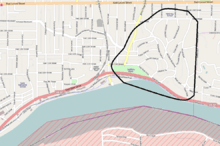

| Coordinates | 41°31′55″N 90°32′14″W / 41.53194°N 90.53722°WCoordinates: 41°31′55″N 90°32′14″W / 41.53194°N 90.53722°W |

| Built | 1861 |

| Governing body | Private |

Location of Camp McClellan in Iowa | |

Camp McClellan is a former Union Army camp in the U.S. state of Iowa that was established in Davenport in August 1861 after the outbreak of the American Civil War.[1] The camp was the training grounds for recruits and a hospital for the wounded. In 1863 it became a prison camp called Camp Kearney for members of the Sioux, or Dakota, tribe that were involved in raids in Minnesota. The camp was decommissioned after the release of the prisoners in 1866.

Camp McClellan

The land the camp was built on belonged to Thomas Russel Allen of St. Louis, Missouri and consisted of over 300 acres (120 ha).[2] The property was directly across the Mississippi River from the Rock Island Arsenal, that was also the site of a prisoner of war camp that held Confederate soldiers. Iowa's Adjutant General Nathaniel B. Baker moved his offices to Davenport and established Camp McClellan as a training camp for the volunteer soldiers. Lieutenant William Hall was responsible for organizing and running the camp.[3] The camp was named in honor of General George B. McClellan.

It was the largest of the five camps that were in and around the city of Davenport.[1] 40,000 of the nearly 80,000 Iowa troops that fought the war passed through its gates.[4] They were also treated in the camp's hospital and mustered out from the camp when the war was over. J. W. Willard was given the contract to construct the necessary buildings and a local company, French & Davis, provided the lumber. They built a dozen frame buildings with 52 double berths for bunks, a mess hall, a commissary, a canteen, a granary and officers quarters. There were enough stalls for over 100 horses. More barracks were completed as quickly as possible because of the large number of recruits that were coming into the camp. A thousand recruits would have been at Camp McClellan at one time after it first opened.[2] Because of the haste, the quarters were poorly constructed and started to leak. Lieutenant Colonel Hall was put in charge to bring the camp up to military standards, maximize security and training efficiency. Colonel Hare of Muscatine, Iowa took over for Lieutenant Colonel Hall on October 11, 1861.[3]

Camp McClellan was the rendezvous of the Eighth, Eleventh, Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Sixteenth regiments of infantry, and also of recruits for the older regiments.[5] The number of troops at the camp was diminished by April 1862 and the Relief Association of Davenport began to refit the camp for an army hospital. However, it was thought the war would soon be over and it was decided that the camp was needed as a prison camp and so walls were built. Despite these plans the war raged on and the number of recruits increased, especially after the draft was instituted.

As the sick and wounded returned from the war, they were brought to the camp's hospital. It contained a pharmacy, clean rooms, and a dietary kitchen that were influenced by Iowa Sanitary Agent Annie Wittenmyer.

Camp Kearney

Camp McClellan became a prison camp of a different kind in 1863. The federal government imprisoned 277 male members of the Sioux tribe, 16 women and two children and one member of the Ho-Chunk tribe, also known as the Winnebago. The men were involved in the Dakota War of 1862 in Minnesota and were held in the camp as prisoners because President Abraham Lincoln commuted their death sentences. It was felt that Davenport was far enough away from Minnesota to protect the Native Americans from lynch mobs. The steamboat Favorite arrived from Mankato, Minnesota on April 25. The prisoners were taken to their quarters without incident. They were given beef and four bushels of corn per day, and ten of the women were assigned to cook. They were also given bread, which they did not like.

A wall was built in December 1863 along the western road that traveled through the camp so as to separate the Native Americans from the recruits. The prison camp portion was renamed Camp Kearney and it was reconfigured to house the guards and the officers. Conditions in the camp became unsanitary and there was some hostility on the part of local citizens that the native Americans were there.[3] The hostile sentiments died down enough that labor parties were taken to work in the nearby farm fields. Major Ten Broeck and Captain Judd, who were in charge of the prison, assured the community that they would be kept safe.

President Lincoln pardoned and freed 27 of the Sioux in August 1864. and they were sent to the Dakota Territories. On April 10, 1866 President Andrew Johnson released the 177 remaining prisoners from the camp to a reservation in Santee, Nebraska. The rest of the Native Americans who were held prisoner died in the camp and were buried in unmarked graves in the vicinity.[3]

Scientists from the Davenport Academy of Natural Science opened four graves on July 25, 1878.[3] They removed several skulls for study and the Putnam Museum, as the Academy is now called, retained the skulls in their collection until the state of Iowa enacted burial site protection and reburial laws. In 1986 the Putnam Museum transferred the skeletal remains in its collection to the Office of the State Archeologist of Iowa. The 23 skulls in the collection were given to the Dakota tribe at Morton, Minnesota for burial. In 2005 the Dakota held a memorial ceremony on the former site of Camp Kearney.

Aftermath

After General Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, the War Department ordered that the camp fire one hundred guns and turn out the military in full regalia. As the Gazette, a local paper, commented, “There being no cannon here and but little military, he (Major Miller) did the best he could.”[3] The following week the camp held a special meeting and ceremony to mourn the death of President Lincoln. The camp then received and mustered out the remaining troops. In August 1865 a fire destroyed the headquarters building. The hospital was closed on October 5, 1865.

The camp was decommissioned and the buildings were torn down after the Native Americans left Camp Kearney.[3] The land was returned to Ann R. Allen, Thomas Russel Allen’s widow. In June 1900 the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) held an encampment on the site.[2] A proposal was submitted to the Iowa Legislature to turn the former camp into a state park. It had the support of Iowa’s Civil War veterans groups, the GAR, and local citizens, but it was not accepted. The area became a residential area, named McClellan Heights, and the southwest portion became Lindsay Park. In 1928 a plaque was placed in the park by the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The plaque reads:

CAMP Mc CLELLAN

HERE WAS LOCATED A MILITARY CAMP DURING THE CIVIL WAR, AT WHICH WERE TRAINED MORE THAN HALF OF THE RECRUITS FROM IOWA.

IN 1862 SEVERAL HUNDRED SIOUX INDIANS WERE IMPRISONED HERE FOLLOWING THE MINNESOTA MASSACRE.

ERECTED BY HANNAH CALDWELL CHAPTER, DAUGHTERS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION 1928

The park held a Civil War Muster and Mercantile Exposition annually in the 1980s. [6][7] The area is now part of two historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places. The Village of East Davenport, which contains the southwest corner of the camp was listed on the register as the Davenport Village on March 17, 1980.[8] Most of what was Camp McClellan is in the McClellan Heights Historic District, and it was listed on the national register November 1, 1984.

References

- 1 2 Svendsen, Marls A., Bowers, Martha H (1982). Davenport where the Mississippi runs west: A Survey of Davenport History & Architecture. Davenport, Iowa: City of Davenport. pp. 16–1.

- 1 2 3 "Articles from the Davenport Times 1900 G.A.R. Encampment". Iowa GenWeb. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Two Sides of Camp McClellan" (PDF). Davenport Public Library. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ↑ Bouilly, Robert, Anderson, Fredrick I. (ed.) (1982). Joined by a River: Quad Cities. Davenport: Lee Enterprises. p. 118.

- ↑ "Chapter XXII: Patriotic Davenport". IAGenWeb. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

- ↑ Renkes, Jim (1994). The Quad-Cities and The People. Helena, MT: American & World Geographic Publishing. p. 54.

- ↑ Williams, Basil, Lewis, Blake (1986). The Quad Cities USA Book. Bettendorf, Iowa: Basil Williams & Associates. p. 32.

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.