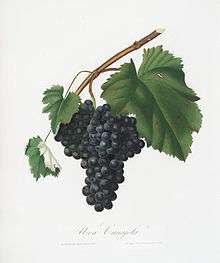

Canaiolo

| Canaiolo | |

|---|---|

| Grape (Vitis) | |

Canaiolo by Giorgio Gallesio | |

| Color of berry skin | Noir |

| Species | Vitis vinifera |

| Also called | Canaiolo nero and other synonyms |

| Origin | Italy |

| Notable regions | Tuscany |

Canaiolo (also called Canaiolo nero or Uva Canina) is a red Italian wine grape grown through Central Italy but is most noted in Tuscany. Other regions with plantings of Canaiolo include Lazio, Marche and Sardegna. In Umbria a white berried mutation known as Canaiolo bianco exist. Together with Sangiovese and Colorino it is often used to create Chianti wine and is an important but secondary component of Vino Nobile di Montepulciano. In the history of Chianti it has been a key component blend and during the 18th century may have been the primarily grape used in higher percentage than Sangiovese. Part of its popularity may have been the grape's ability to partially dry out without rotting for use in the governo method of prolonging fermentation. In the 19th century, the Chianti recipe of Bettino Ricasoli called for Canaiolo to play a supporting role to Sangiovese, adding fruitiness and softening tannins without detracting from the wine's aromas. In the aftermath of the phylloxera epidemic, the Canaiolo vines did not take well to grafting onto new American rootstock and the grape began to steadily fall out of favor. As of 2006, total plantings of Canaiolo throughout Italy dropped to under 7,410 acres (3,000 hectares). Today there are renewed efforts by Tuscan winemakers to find better clonal selections and re-introduce the variety into popular usage.[1]

A white sub-variety exist, known as Canaiolo bianco, which is a permitted grape variety in the Umbrian wine region of Orvieto where is known as Drupeggio.[2] In recent years plantings have been declining.[1]

In Tuscany

Ampelographers believe that Canaiolo is most likely native to Central Italy and perhaps to the Tuscany region. It was a widely planted variety in the Chianti region and most likely was the dominant grape variety in Chianti blends throughout the 18th century. The writings of Italian writer Cosimo Villifranchi noted the grape's popularity and that it was often blended with Sangiovese, Mammolo and Marzemino.[3] Part of Canaiolo's success in the region may have been its affinity for the governo winemaking technique that was used to ensure complete fermentation.[1] At the time various wine faults would plague unstable Chiantis because they were not able to fully complete fermentation and yeast cells would remain active in the wine. The lack of full fermentation was partly due to cooler temperatures following harvest that stuns the yeast and prohibits activity prior to technological advances in temperature control fermentation vessel. The technique of governo was first developed by Chianti winemakers in the 14th century. This involves adding half-dried grapes to the must to stimulate the yeast with a fresh source of sugar that may keep the yeast active all the through the fermentation process.[4] Canaiolo's resistance to rotting while going through the partial drying process made it an ideal grape for this technique.[1]

In the 19th century, the Baron Bettino Ricasoli created the modern Chianti recipe that was predominantly Sangiovese with Canaiolo added for it fruitiness and ability to soften the tannins of Sangiovese. Wine expert Hugh Johnson has noted that the relationship between Sangiovese and Canaiolo has some parallels to how Cabernet Sauvignon is softened by the fruit of Merlot in the traditional Bordeaux style blend.[4] The rise in prominence of Sangiovese herald the decline of Canaiolo as more winemakers rushed to plant more Sangiovese. Outside of Chianti, Canaiolo role in the Sangiovese based on Vino Nobile di Montepulciano was also declining though it was never as prominent as it once was in Chianti. The phylloxera devastation at the end of the 19th century highlighted the unique difficulties that Canaiolo has with grafting as many plantings on new American rootstock failed to take.[1]

Today there are a few vineyards in the Chianti Classico region specializing in Canaiolo, two of them being the family estates of Bettino Ricasoli in Brolio and Gaiole in Chianti as well as a scattering of vineyards in Barberino Val d'Elsa. There are renewed efforts and research in clonal selections to revive the variety in Tuscany.[1]

Other regions

Outside of Tuscany, Canaiolo is also found throughout central Italy with significant plantings in Lazio, Marche and Sardegna. Though there are efforts in Tuscany to revive the variety, plantings throughout the country continue to drop and fell under 7,410 acres (3,000 hectares) in 2006.[1]

Synonyms

Canaiolo is also known under the synonyms Caccione nero, Cacciuna nera, Cagnina, Calabrese, Canaiola, Canaiolo Borghese, Canaiolo Cascolo, Canaiolo Colore, Canaiolo Grosso, Canaiolo nero, Canaiolo nero a Raspo rosso, Canaiolo nero Comune, Canaiolo nero Grosso, Canaiolo nero Minuto, Canaiolo Pratese, Canaiolo Romano, Canaiolo rosso Piccolo, Canaiolo Toscano, Canaiuola, Canaiuolo, Canajola Lastri, Canajolo, Canajolo Lastri, Canajolo nero Grosso, Canajolo Piccolo, Canajuola, Canajuolo nero Comune, Canina, Cannaiola, Cannajola, Colore, San Giovese, Tindillaro, Tindilloro, Uva Canaiolo, Uva Canajuola, Uva Canina, Uva Colore Canaiola, Uva Dei Cani, Uva Donna, Uva Fosca, Uva Grossa, Uva Marchigiana, Uva Merla, and Vitis Vinifera Etrusca.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Robinson, Jancis, ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (third ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 133–134. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ↑ Ewing-Mulligan, Mary; Ed McCarthy (2001). Italian Wines for Dummies. New York: Hungry Minds. p. 178. ISBN 0-7645-5355-0. OCLC 48026599.

- ↑ Robinson, Jancis, ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (third ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 162–163. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- 1 2 Johnson, Hugh (1989). Vintage: The Story of Wine. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 414–420. ISBN 0-671-68702-6. OCLC 19741999.

- ↑ "Canaiolo nero". Vitis International Variety Catalogue. 17 June 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2014.