Captain Moonlite

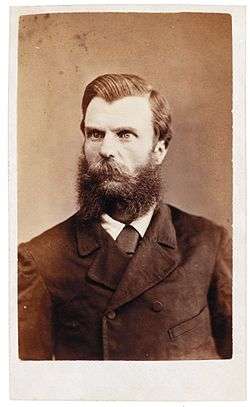

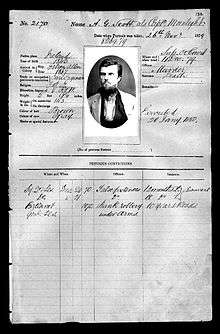

| Andrew George Scott | |

|---|---|

|

Captain Moonlite | |

| Born |

before 5 July 1842 Rathfriland, Ireland |

| Died |

20 January 1880 (aged 38) Sydney |

| Other names | Captain Moonlite |

| Occupation | Bushranger |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Criminal status | Executed by hanging |

Andrew George Scott (baptised 5 July 1842 – 20 January 1880), also known as Captain Moonlite, was an Irish-born Australian bushranger.

Early life

Scott was born in Rathfriland, Ireland, son of Thomas Scott, an Anglican clergyman and Bessie Jeffares.[1] His father's intention was that he join the priesthood, but Scott instead trained to be an engineer, completing his studies in London.

The family moved to New Zealand in 1861, with Scott intending to try his luck in the Otago goldfields. However, the Maori Wars intervened and Scott signed up as an officer and fought at the battle of Orakau where he was wounded in both legs.

After a long convalescence Scott was accused of malingering, and court-martialed. He gave his disquiet at the slaughter of women and children during the siege as the source of his objection to returning to service.

In Melbourne, he met Bishop Charles Perry and, in 1868, he was appointed lay reader at Bacchus Marsh, Victoria, with the intention of entering the Anglican priesthood on the completion of his service. He was then sent to the gold mining town of Mount Egerton.

Bushranging career

On 8 May 1869, Scott was accused of disguising himself and forcing bank agent Ludwig Julius Wilhelm Bruun, a young man whom he had befriended, to open the safe. Bruun described being robbed by a fantastic black-crepe masked figure who forced him to sign a note absolving him of any role in the crime. The note read "I hereby certify that L.W. Bruun has done everything within his power to withstand this intrusion and the taking of money which was done with firearms, Captain Moonlite, Sworn."

Bruun claimed the man sounded like Scott but no gold was found in Scott's possession. Scott in turn accused Bruun and local school teacher James Simpson of the crime, who then became the principal suspects in the minds of police. Scott left for Sydney soon afterwards.

Scott resigned his lay-readership, bought two horses, kept a groom, and played as a gentleman. Between July and December 1869 he was absent and was supposed to have made a voyage to Fiji, but on 28 December he was in Sydney selling at the mint 120 ounces of retorted gold, resembling in fineness and other qualities the metal taken from the bank at Egerton, although no thought of connecting one lot with the other was then entertained. The proceeds of this sale, about £550, he deposited in the Union Bank, Sydney, on 31 December, and this deposit he subsequently supplemented with another of £200, drawing thereupon by cheques in his own name up to November 1870 when his account was finally closed. After this he went to the Maitland district, near Newcastle and was there convicted on two charges of obtaining money by false pretences for which he was sentenced to twelve and eighteen months' imprisonment. Of these concurrent terms, Scott served fifteen months, at the expiration of which time he returned to Sydney where, in March 1872, he was arrested on the charge of robbing the Egerton Bank and forwarded to Ballarat for examination and trial.

He succeeded in escaping gaol by cutting a hole through the wall of his cell, he gained an entrance into the cell adjoining, which was occupied by another prisoner, who was as desirous of escaping as himself. Together they seized the warder when he came on his rounds, gagged him, and tied him up, and making use of his keys proceeded to other cells, and liberated four other prisoners, and the six men succeeded in escaping over the wall, by means of blankets cut into strips, which they used as a rope. Scott was subsequently re-captured, and held safely until he could be tried. In July he was tried before judge Sir Redmond Barry at the Ballarat Circuit Court, when, by a series of cross-examinations of unprecedented length, conducted by himself after rejecting his counsel, he spread the case over no less than eight days, but was at last convicted, and sentenced to 10 years' hard labour. Despite some evidence against him, Scott claimed innocence in this matter until his dying day.

Scott only served two-thirds of his sentence of 10 years, was released from HM Prison Pentridge in March 1879 and after his release he made a few pounds by lecturing on the enormities of Pentridge Gaol. On regaining freedom, Scott met up with James Nesbitt, a young man whom he had met in prison. While some disagree on the grounds of speculation, he is considered by many to be Scott's lover and there is a significant primary resource that supports this reading. Scott's actual handwritten letters, currently held in the Archives Office of NSW, profess this love . While it is difficult to definitively claim the exact nature of Scott and Nesbitt's sexual practices, it can certainly be said that their relationship was an overtly romantic one. With the aid of Nesbitt, Captain Moonlite began a career as a public speaker on prison reform trading on his tabloid celebrity.

However this reputation came back to bite him. Throughout this period Scott was harried by the authorities and by the tabloid press who attempted to link him to numerous crimes in the colony and printed fantastic rumours about supposed plots he had underway.

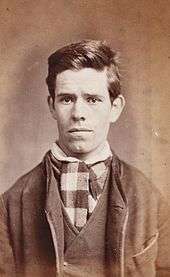

At some time during this period Scott seems to have decided to live up to this legend and assembled a gang of young men, with Nesbitt as his second in command and the others being Thomas Rogan (21), Thomas Williams (19), Gus Wreneckie (15) and Graham Bennet (18). Scott met these young men through his lecture tours or through brothels.

The gang commenced their careers as bushrangers near Mansfield, in Victoria. While travelling through the Kellys' area of operation, the gang were frequently mistaken for The Kelly Gang and took advantage of this to receive food and to seize guns and ammunition from homesteads. Inspecting Superintendent of Police John Sadleir, made a highly improbable claim that Scott sent word to infamous bushranger Ned Kelly, asking to join forces with him but Kelly sent back word threatening that if Scott or his band approached him he would shoot them down. Scott seems to have never received the reply as his gang left Victoria in the later part of 1879, after operating there for a short time. They travelled north across the border into New South Wales to look for work, far from the police surveillance that stymied any opportunity of employment in Victoria. It was in the southern district of the New South Wales colony that they entered upon the full practice of their profession.

In one act they made themselves notorious. On Saturday evening, 15 November 1879 they entered the little settlement of Wantabadgery, about 28 miles from Gundagai, and proceeded to "bail up" all the residents.[2]

Capture, trial and hanging

Scotts gang bailed up the Wantabadgery Station near Wagga Wagga on 15 November 1879 after being refused work, shelter and food. By this stage they were on the verge of starvation, after spending cold and rainy nights in the bush and in Moonlite's words succumbed to "desperation," terrorising staff and the family of Claude McDonald, the station owner. Scott also robbed the Australian Arms Hotel of a large quantity of alcohol and took prisoner the residents of some other neighbouring properties- bringing the number of prisoners to 25 in total.[3]

One man, Ruskin, escaped in an attempt to warn others, but was caught and subject to a mock trial- the jury of his fellow prisoners finding him "Not Guilty". Another station-hand attempted to rush Scott but was overpowered.

A small party of four mounted troopers eventually arrived, but Scott's well armed gang captured their horses and held them down with gunfire for several hours until they retreated to gather reinforcements- at which point the gang slipped out.[4]

The gang then holed up in the farmhouse of Edmund McGlede until surrounded by a reinforcement of 5 extra troopers led by Sergeant Carroll.

As the boy Wreneckie was running from a fence to reach a better position, he was shot through the side dead. The police gradually advanced from tree to tree, and drove the remaining desperadoes into a detached back kitchen. Sergeant Carroll led an assault upon the kitchen, and in this rally Constable Edward Webb-Bowen was fatally wounded, a bullet from Scott's rifle entering his neck, and lodging near the spine.

Nesbitt was also shot and killed, attempting to lead police away from the house so that Scott could escape. When Scott saw Nesbitt shot down and was distracted, McGlede took the opportunity to disarm the gang leader and with the other members wounded, or captured on attempting to flee, the fire fight came to a close. Rogan succeeded in escaping, but was found next day under a bed in McGlede's house. According to newspaper reports at the time, Scott openly wept at the loss of his dearest and closest companion. As Nesbitt lay dying, 'his leader wept over him like a child, laid his head upon his breast, and kissed him passionately'.

Scott denied shooting Webb-Bowen. Witnesses confirmed that Scott was armed with a Snider rifle and the policeman had died from a bullet fired by a Colt’s pistol. It was never discovered who used that weapon in the firefight, policeman or civilian, and it was not found afterwards. Scott was found guilty despite deflecting as much blame for the robbery from his companions as possible and the jury recommended mercy for three of them.

Scott and Rogan were hanged together in Sydney at Darlinghurst gaol at 8 o'clock on 20 January 1880, on Scott's father's birthday.[5] While awaiting his hanging Scott wrote a series of death-cell letters which were discovered by historian Garry Wotherspoon. Scott went to the gallows wearing a ring woven from a lock of Nesbitt's hair on his finger[6] and his final request was to be buried in the same grave as his constant companion, "My dying wish is to be buried beside my beloved James Nesbitt, the man with whom I was united by every tie which could bind human friendship, we were one in hopes, in heart and soul and this unity lasted until he died in my arms." His request was not granted by the authorities of the time, but in January 1995, his remains were exhumed from Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney and reinterred at Gundagai next to Nesbitt's grave.[7]

References

- ↑ "Scott, Andrew George (Captain Moonlite) (1842–1880)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 6. Australian National University and Melbourne University Press. 1976. pp. 94–95. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- ↑ "Novelist.". Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916). WA: National Library of Australia. 11 August 1903. p. 3. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ↑ "A TRUE NARRATIVE.". Independent (Footscray, Vic. : 1883 – 1922). Footscray, Vic.: National Library of Australia. 20 December 1890. p. 3. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ↑ "NEW SOUTH WALES.". The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954). Hobart, Tas.: National Library of Australia. 23 December 1879. p. 4. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ↑ "EXECUTION OF THE BUSHRANGERS.". Kerang Times and Swan Hill Gazette (Vic. : 1877 – 1889). Vic.: National Library of Australia. 23 January 1880. p. 4 Edition: WEEKLY. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ↑ A queer bushranger: The tale of Captain Moonlite, by Jeff Sparrow, in the Monthly; published November 2015; retrieved February 16, 2016

- ↑ "Gundagai". Walkabout: Australian Travel Guide. Fairfax Digital. Retrieved 12 July 2006.

External links

![]() Media related to Captain Moonlite at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Captain Moonlite at Wikimedia Commons