Circulating library

A circulating library (also known as lending libraries and rental libraries) was first and foremost a business. The intention was to profit from lending books to the public for a fee.[1]

Overview

Circulating libraries offered an alternative to the large number of readers who could not afford the price of new books in the nineteenth century but also desired to quench their desire for new material. Many circulating libraries were perceived as the provider of sensational novels to a female clientele but that was not always the case. Many private circulating libraries in Europe were created for scientific and/or literary audiences. In Britain, readers in the middle classes depended on these institutions to provide access to the latest fiction novels that required a substantial subscription that many lower class readers couldn't afford.[2]

Circulating libraries rented out bestsellers in large numbers, allowing publishers and authors to increase their readership and increase their earnings, respectively. Publishers and circulating libraries became decreasingly dependent on each other in the nineteenth century for their mutual profit. Circulating libraries also influenced book publishers to keep producing expensive volume-based books instead of a single-volume format (see Three-volume novel). However, when bestselling fiction titles went out of fashion quickly, many circulating libraries were left with inventory they could neither sell nor rent out. This is one of the reasons why circulating libraries, such as Charles Edward Mudie, were eventually forced to close their doors in response to cheaper alternatives.[2]

It is complicated to precisely define circulating libraries and specifically what separates them from other types of libraries. In the time period of circulating libraries, there were other libraries, such as subscription libraries, that operated in a similar fashion but were not the same.[1][3] However, when both types of libraries were commonplace, the terms circulating libraries and subscription libraries “were completely interchangeable."[4] It was logical that they were considered to be the same since both libraries circulated books and charged a subscription fee. The libraries differed in their intent. Circulating libraries’ intent was financial gain, and subscription libraries intended to obtain literary and scholarly works to share with others.[1][5]

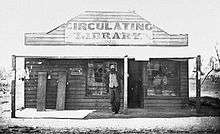

Circulating libraries were popular in the 18th and 19th century and were located in large and small communities. Usually they were operated out of stores that sold other items such as newspapers and books. Sometimes they were in stores that sold items completely unrelated to books. The fees were for long periods of time such ranging from several months to a year. Eventually the fees changed to daily rates to try to entice customers in some libraries.[6]

One difference between circulating libraries and other libraries was that their collection reflected public demand, which led to larger collections of fiction.[1][6] When circulation decreased, the books were sold. Another difference was the customers were often female. These factors contributed to the popularity of circulating libraries.[6] Circulating libraries were the first to serve women and actively seek out their patronage. It was not coincidence that some of these libraries were located in millinery and stationary stores and midwives' offices.[7]

Early circulating libraries

- 1725, Allan Ramsay opened the first circulating library in Edinburgh, Scotland.[3]

- 1728, The first circulating library in England was opened by James Leake.[3]

- 1762, The first circulating library in America was opened in Annapolis, Maryland by William Rind.[1]

Criticism of circulating libraries and novels

The late 18th century was when novels became commonplace. The demand for novels was high but the cost of them made them inaccessible for many. They held wide appeal because they were less complex than more scholarly types of literature. However novels were not greeted with an overwhelmingly popular reception.[8]

Aspects of novels were realistic, which made them appealing and relatable. The elements of novels that made them sensational and alluring were the parts that deviated from what would usually happen in reality. Society feared that people, mainly women, would not be able to differentiate between the realistic and completely fictional elements. Basically the argument against novels was that it would cause people to have unrealistic expectations of life.[8]

Circulating libraries were highly criticized at the height of their popularity for being providers of novels.[6][8] The views about novels and their readers, sellers, and writers went beyond simple criticism to being slanderous. Much of the information known about criticism of novels comes from a variety of public and privately written sources.[8]

Publishing

Some circulating libraries were publishers although many did not have widespread distribution for the works they printed. By the end of the 18th century, they had increased the amount of fiction they published. They favored publishing works from women whereas other publishers still favored works by men.[9]

It was common for people to publish their works anonymously. Circulating library publishers were known for publishing anonymous works, and it is believed that many of the ones they published were written by women. Circulating library publishers were not viewed as favorably as other major publishers since they printed works that were considered unsavory by society. People may have wanted their works to be anonymous to avoid the stigma of being associated with a publisher with a dubious reputation.[9]

Decline

By the beginning of the 20th century the ways people procured books had changed, and circulating libraries were no longer the favored way of obtaining them.[3] The biggest contributor to the contraction of circulating libraries was reduced the price of books, which made them more accessible to the public, so that they were less reliant on circulating libraries. In an attempt to compensate for the loss of revenue, the subscription fees were lessened to daily rates down from monthly or yearly ones.[6]

Commercial circulating libraries were still common into the 20th century, although as modern public libraries became commonplace, this contributed to their decline. Another contributing factor was the introduction of paperback books, which were less expensive to purchase.[1]

In the UK, the retail chain WHSmith ran a library scheme from 1860, which lasted until 1961, when the library was taken over by that of Boots the Chemist. This, founded in 1898 and at one time to be found in 450 branches, continued until the last 121 disappeared in 1966.[10]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rassuli, Kathleen M.; Hollander, Stanley C. (2001). "Revolving, Not Revolutionary Books: The History Of Rental Libraries Until 1960". Journal of Macromarketing. 21 (2).

- 1 2 Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Getty Publications. p. 147. ISBN 9781606060834.

- 1 2 3 4 Manley, K. A. (2003). "Scottish Circulating And Subscription Libraries As Community Libraries". Library History. 19 (3).

- ↑ Manley, K. A. (2003). "Scottish Circulating And Subscription Libraries As Community Libraries". Library History. 19 (3): 185.

- ↑ Valentine, Patrick M. (2011). "America's Antebellum Social Libraries: A Reappraisal In Institutional Development". Library & Information History. 7 (1).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Croteau, Jeffrey (2006). "Yet More American Circulating Libraries: A Preliminary Checklist Of Brooklyn (New York) Circulating Libraries". Library History. 22 (3).

- ↑ Freeman, Robert & Hovde, David. (2003). Libraries to the People: Histories of Outreach. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company. P. 13. ISBN 0-7864-1359-X

- 1 2 3 4 Vogrinčič, Ana (2008). "The Novel-Reading Panic in 18th-Century in England: An Outline of an Early Moral Media Panic". Medijska Istraživanja. 14: 109–112. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- 1 2 Jacobs, Edward (2003). "Eighteenth-Century British Circulating Libraries And Cultural Book History". Book History. 6: 3–9.

- ↑ http://usvsth3m.com/post/did-you-know-that-until-the-1960s-boots-the-chemist-was-also-a-library