Comparison of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia

Both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are characterized as psychiatric disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition (DSM-5). Schizophrenia is a primary psychotic disorder, and bipolar disorder is a primary mood disorder but can also involve psychosis. However, because of some similar symptoms, differentiating between the two can sometimes be difficult; indeed, there is an intermediate diagnosis schizoaffective disorder.

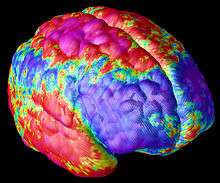

While reported and observed symptoms are a main way to diagnose either disorder, recent research studies are allowing psychiatrists to use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to try to find better, definite markers. Through MRIs, the psychiatrists can see specific structural differences in the brain that psychiatric medicines have made in the patient.[1] These differences include volume of gray matter, neuropathological size differences variations, and cortical thickness, which then associated with cognitive differences on tests. These differences may sometimes be seen throughout the lifespan of the diseases, and often occur soon after the initial episode. Although the diseases are different, some of their treatments are similar, because of some shared symptoms.

Etiology and epidemiology

Both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia appear to result from gene–environment interaction. Evidence from numerous family and twin studies indicates a shared genetic etiology between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.[2][3] Geoffroy, Etain, and Houenou note that the largest family study available found a combined heritability for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia of approximately 60%, with environmental factors accounting for the remainder.[3] Genetic contributions to schizoaffective disorder appear to be entirely shared with those contributing to schizophrenia and mania.[2]

Bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia each occur in approximately 1% of the population; schizoaffective disorder is estimated to occur in less than 1% of the population.[2]

Symptoms

During severe episodes of mania or depression people with bipolar disorder may have psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusions.[4] When experiencing hallucinations or delusions, people with schizophrenia often seem to "lose touch" with reality.[5] "Voices" are the most common type of hallucination in schizophrenia.[5] In bipolar disorder, the psychotic symptoms tend to reflect the person's extreme depressed or elated mood (mood congruence).[4] People with either disorder may have delusions of grandeur in which they believe they are a famous person or historical figure.[4][5] When psychotic symptoms are present, bipolar disorder is sometimes misdiagnosed as schizophrenia.[4]

Other symptoms of schizophrenia, including lack of pleasure[6] difficulty making decisions, and difficulty focusing,[7] are similar to some symptoms of depression seen in bipolar disorder.[4] Jumping from one idea to another and being unusually distracted during a manic episode[4] may resemble "disorganized thinking," characteristic of schizophrenia.[5]

Substance abuse is a complicating factor for both conditions, making symptoms more difficult to recognize as a mental illness[4][8] and interfering with treatment efficacy and adherence.[8]

Gray Matter

Patients with schizophrenia may have some gray matter volume loss in both hemispheres of the brain.[9] The most significant losses are typically in the left thalamus and right caudate, and this loss extends into the cerebrum, parahippocampal gyrus, and the hippocampus.[9] There are increases in the temporal and parietal lobes, along with the anterior cerebellum.[9] When patients with schizophrenia are compared to healthy participants, there is a decrease in gray matter volume in prefrontal and temporal regions.[10] The only region in which the volume increases for gray matter is within the right cerebellum,[10] an area that contributes to the cognitive, affective, perceptual, and other deficits seen in schizophrenia.[11]

Unlike schizophrenia, bipolar disorder has very little differences for gray matter volume.[9][10] Overall, there is no difference between bipolar patients and healthy patients.[10]

Neuropathological

Magnetic resonance imaging studies found that schizophrenia is associated with significantly smaller amygdala volume compared to both healthy controls and participants with bipolar disorder.[12] Although there was no significant difference in amygdala volume between individuals with bipolar disorder and controls, amygdala size in the group with bipolar disorder was positively correlated with treatment using mood stabilizer medications[12] This is important to consider as mood stabilizers like lithium appear to have protective and growth-stimulating effects in multiple regions of the brain, including the amygdala.[13] Thus, it is possible that the size differences of the amygdala are due to medication rather than disease. Even so, the amygdala might still be a place of partially shared pathophysiology between these disorders.[14]

Besides the amygdala, there are other neuropathological areas of degeneration as well; the overall brain volume can also be measured. Research shows that the overall brain volume is not statistically significantly different between patients with bipolar disorder and patients with schizophrenia, except when making comparisons in the intracranial volume.[15] A larger intracranial volume is present in the brains in bipolar disorder, but no variation occurs in the brains of people with schizophrenia.[15]

Treatment

Because neither disorder is “curable,” treatments are meant to control symptoms and make them more tolerable. Treatments for the diseases include medication, psychotherapy, and others.

Medication

Mood-stabilizers, such as lithium, are the primary medication treatment bipolar disorder.[16] Atypical antipsychotic medications may also be used for bipolar disorder, often in combination with antidepressant medications.[16] Antipsychotics and atypical antipsychotics are the major classes of medications used to treat schizophrenia.[17]

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is a treatment both types of disorder patients use. They guide the patients in their thoughts, and use communication or behavioral work as a means of healing. Families of the affected also benefit from this treatment, as they can sit on sessions and talk to the therapist as well.[18][19]

Other

Rehabilitation is one of several psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. It involves social and job-skills training to improve an individual's ability to function in society.[19] Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be used to treat bipolar disorder when other treatments are ineffective or when medication would be dangerous because of another medical condition.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ "Long-term Antipsychotic Treatment and Brain Volumes:A Longitudinal Study of First-Episode Schizophrenia" Authors Beng-Choon Ho, MRCPsych; Nancy C. Andreasen, MD, PhD; Steven Ziebell, BS; Ronald Pierson, MS; Vincent Magnotta, PhD. February 7, 2011

- 1 2 3 Cosgrove, Victoria E; Suppes, Trisha (14 May 2013). "Informing DSM-5: biological boundaries between bipolar I disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia". BMC Medicine. 11: 127. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-127. PMC 3653750

. PMID 23672587.

. PMID 23672587.

- 1 2 Geoffroy, Pierre Alexis; Etain, Bruno; Houenou, Josselin (14 Oct 2013). "Gene × environment interactions in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: evidence from neuroimaging". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 4: 136. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00136. PMC 3796286

. PMID 24133464.

. PMID 24133464.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 NIMH 2012, What are the signs and symptoms of bipolar disorder?.

- 1 2 3 4 NIMH 2009, What are the symptoms of schizophrenia? § Positive symptoms.

- ↑ NIMH 2009, What are the symptoms of schizophrenia? § Negative symptoms.

- ↑ NIMH 2009, What are the symptoms of schizophrenia? § Cognitive symptoms.

- 1 2 NIMH 2009, What about substance abuse?.

- 1 2 3 4 Watson, David R.; Anderson, Julie M.E.; Bai, Feng; Barrett, Suzanne L.; McGinnity, T. Martin; Mulholland, Ciaran C.; Rushe, Teresa M.; Cooper, Stephen J. (1 February 2012). "A voxel based morphometry study investigating brain structural changes in first episode psychosis". Behavioural Brain Research. 227 (1): 91–99. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2011.10.034. PMID 22056751. (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 Yüksel, C; McCarthy, J; Shinn, A; Pfaff, DL; Baker, JT; Heckers, S; Renshaw, P; Ongür, D (July 2012). "Gray matter volume in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with psychotic features". Schizophrenia Research. 138 (2–3): 177–82. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.03.003. PMC 3372612

. PMID 22445668.

. PMID 22445668. - ↑ Picard, Hernàn; Amado, Isabelle; Mouchet-Mages, Sabine; Olié, Jean-Pierre; Krebs, Marie-Odile (January 2008). "The Role of the Cerebellum in Schizophrenia: an Update of Clinical, Cognitive, and Functional Evidences". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 34 (1): 155–172. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm049. PMC 2632376

. PMID 17562694.

. PMID 17562694.

- 1 2 Arnone, D; Cavanagh, J; Gerber, D; Lawrie, SM; Ebmeier, KP; McIntosh, AM (September 2009). "Magnetic resonance imaging studies in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: meta-analysis". British Journal of Psychiatry. 195 (3): 194–201. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059717. PMID 19721106.

- ↑ Machado-Vieira, Rodrigo; Manji, Husseini K; Zarate, Carlos A, Jr (June 2009). "The role of lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder: convergent evidence for neurotrophic effects as a unifying hypothesis". Bipolar Disorders. 11 (Suppl 2): 92–109. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00714.x. PMC 2800957

. PMID 19538689.

. PMID 19538689. - ↑ Mahon, PB; Eldridge, H; Crocker, B; Notes, L; Gindes, H; Postell, E; King, S; Potash, JB; Ratnanather, JT; Barta, PE (July 2012). "An MRI study of amygdala in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder". Schizophrenia Research. 138 (2–3): 188–91. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.04.005. PMC 3372630

. PMID 22559949.

. PMID 22559949. - 1 2 Hulshoff Pol, HE; van Baal, GC; Schnack, HG; Brans, RG; van der Schot, AC; Brouwer, RM; van Haren, NE; Lepage, C; Collins, DL; Evans, AC; Boomsma, DI; Nolen, W; Kahn, RS (April 2012). "Overlapping and segregating structural brain abnormalities in twins with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder". Archives of General Psychiatry. 69 (4): 349–59. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1615. PMID 22474104.

- 1 2 NIMH 2012, Medications.

- ↑ NIMH 2009, How is schizophrenia treated? § Antipsychotic medications.

- ↑ NIMH 2012, Psychotherapy.

- ↑ NIMH 2012, Other treatments.

-

This article incorporates text from a scholarly publication published under a copyright license that allows anyone to reuse, revise, remix and redistribute the materials in any form for any purpose: Cosgrove & Suppes 2013. Please check the source for the exact licensing terms.

This article incorporates text from a scholarly publication published under a copyright license that allows anyone to reuse, revise, remix and redistribute the materials in any form for any purpose: Cosgrove & Suppes 2013. Please check the source for the exact licensing terms. -

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Institute of Mental Health.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Institute of Mental Health.

- NIMH (2012). "Bipolar Disorder in Adults". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- NIMH (2009). "Schizophrenia". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 22 September 2014.