Confederation Poets

"Confederation Poets" is the name given to a group of Canadian poets born in the decade of Canada's Confederation (the 1860s) who rose to prominence in Canada in the late 1880s and 1890s. The term was coined by Canadian professor and literary critic Malcolm Ross, who applied it to four poets – Charles G.D. Roberts (1860–1943), Bliss Carman (1861–1929), Archibald Lampman (1861–1899), and Duncan Campbell Scott (1862–1947) – in the Introduction to his 1960 anthology, Poets of the Confederation, which began: "It is fair enough, I think, to call Roberts, Carman, Lampman, and Scott our 'Confederation poets.'"[1]

The term has also been used since to include William Wilfred Campbell (?1860-1918) and Frederick George Scott (1861–1944),[2] sometimes Francis Joseph Sherman (1871–1926),[3] sometimes Pauline Johnson (1861–1913) and George Frederick Cameron (1854–1885),[4] and Isabella Valancy Crawford (1850–1887) as well.[5]

History

The Confederation Poets were the first Canadian writers to become widely known after Confederation in 1867.[6]

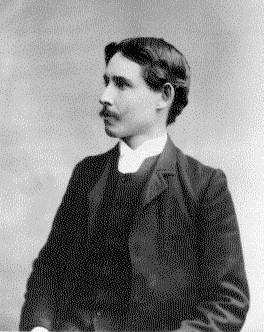

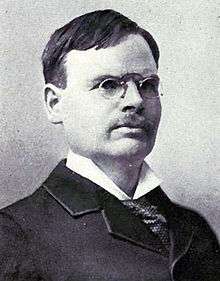

Charles G. D. Roberts (recognized in his lifetime as "the father of Canadian poetry") led the group,[6] which had two main branches: One, in Ottawa, consisted of the poets Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott, and William Wilfred Campbell. The other were Maritime poets, including Roberts and his cousin, Bliss Carman. The four major poets in the group were Roberts, Carman, Lampman and Scott, with Lampman "most often regarded as the finest poet" in the group, according to the Twentieth-Century Literary Movements Dictionary.[6]

The group, which thrived from the 1890s to the 1920s, generally paid attention to classical forms and subjects, but also realistic description, some exploration of innovative technique and, in subject matter, an examination of the individual's relationships both to the natural world and modern civilization.[6]

None of the above poets ever used the term "Confederation Poets", or any other term, for themselves as a distinct group. Nothing indicates that any of them considered themselves a group. In fact, they "were in no way a cohesive group."[7] As a group, the "Confederation Poets" were formed by a retroactive process of canonization: "Malcolm Ross's retrospective application of the term ‘Confederation poets’ is a good example of canon-making along national lines.[5]

Despite the fact there never was such a group historically, there may be good reasons to treat the Confederation Poets as a distinct group in hindsight. First of all, "Roberts, Lampman, Carman, and Scott were among the first really good poets writing in the recently formed Dominion of Canada".[5] For that matter, they were writing the first exceptional poetry ever written in the new country. As "Confederation Poet" Archibald Lampman said about encountering "Confederation Poet" Charles G.D. Roberts's work:

One May evening somebody lent me Orion and Other Poems, then recently published. Like most of the young fellows about me I had been under the depressing conviction that we were situated hopelessly on the outskirts of civilization, where no art and no literature could be, and that it was useless to expect that anything great could be done by any of our companions, still more useless to expect that we could do it ourselves. I sat up all night reading and rereading Orion in a state of the wildest excitement and when I went to bed I could not sleep.[8]

In addition: "There are several good reasons, both biographical and literary, for grouping them together. All were close contemporaries born in the early 1860s. Roberts and Carman were cousins; Roberts briefly edited Goldwin Smith's Toronto literary magazine The Week, in which Carman published his first poem."[5] Lampman also published in the Week, and he and Roberts became friends by mail. In the early 1890s, when Carman worked on the editorial staffs of The Independent and The Chapbook, and other American magazines, he published poems by the other three.

At the Mermaid Inn

"Lampman and Scott were close friends; with Wilfred Campbell they began the column "At the Mermaid Inn" [9] in the Toronto Globe, in 1892."[5]

The original idea was to raise some money for Campbell, who was in financial trouble. As Lampman wrote to a friend: "Campbell is deplorably poor.... Partly in order to help his pockets a little Mr. Scott and I decided to see if we could get the Toronto “Globe” to give us space for a couple of columns of paragraphs & short articles, at whatever pay we could get for them. They agreed to it; and Campbell, Scott and I have been carrying on the thing for several weeks now."[10]

"Scott ... came up with the title for it. His intention was to conjure up a vision of The Mermaid Inn Tavern in old London where Sir Walter Raleigh founded the famous club whose members included Ben Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher, and other literary lights."[11]

Lampman and Scott "found it difficult to keep a rein on Campbell’s frank expression of his heterodox opinions. Readers attacked the Globe after Campbell outlined the history of the cross as a mythic symbol, and his apology for overestimating their intellectual capacities did little to redeem him in the eyes of either the Globe or his fellow contributors to the column."[12]

The column ran only until July 1893. In that year Campbell was "given a permanent position in the Department of Militia and Defence,",[12] and his financial crisis eased. So as there was no longer the need for it, the column came to an end.

Poetry

The Confederation writers' poetry, "although striving for a certain Canadian quality, was very much the offspring of English Victorian verse."[13]

As is clear from the Lampman quote, what Roberts was striving for, and what Lampman was responding to, was not the idea of a distinctly Canadian poetry, a poetry 'of our own'. Rather, it was that of a Canadian, 'one of our own,' writing "great" poetry. Irrespective of their explicit statements about nationalism, in terms of their aesthetics the Confederation Poets were not Canadian nationalists, but thorough-going cosmopolitans. They did not aim to create a Canadian literature; they aimed at a world class literature created by Canadians.

In the late 19th century world class literature meant British literature, which was Victorian by definition. The Confederation Poets were writing in the tradition of late Victorian literature; and like most in that tradition, the most obvious influences on them were the Romantics.

One thing that was uniquely Canadian about that was that it was being attempted by Canadians (for the first time, which is what excited Lampman). Another thing, just as new and potentially more exciting for the Canadian reader, was that for the first time there was poetry worth reading that talked about the country where he lived: Roberts's Tantramar, Carman's Grand Pré, Lampman's Lake Temiscamingue, Scott's Height of Land, Campbell's Lake Region.

"The impact of Lampman, Carman, Roberts, and D.C. Scott on Canadian poetry was very much like the impact of Thomson and Group of Seven painting two decades later," wrote literary critic Northrop Frye. "Contemporary readers felt that whatever entity the word Canada might represent, at least the environment it described was being looked at directly."[14]

Frye saw other parallels between those four poets and the Group of Seven: "Like the later painters, these poets were lyrical in tone and romantic in attitude; like the painters, they sought for the most part uninhabited landscape."[14]

The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature says: "All four poets drew much of their inspiration from Canadian nature, but they were also trained in the classics and were cosmopolitan in their literary interests. All were serious craftsmen who assimilated their borrowings from English and American writing in a personal mode of expression, treating the important subjects and themes of their day, often in a Canadian setting. They have been aptly called the first distinctly Canadian school of writers."[15]

Evaluation

Canonization

Like Thomson and the Group of Seven, the Confederation Poets became the new country's canon. This canon-building began even in their lifetimes.

In 1883 Roberts's friend Edmund Collins published his biography, The Life and Times of Sir John A. MacDonald, which devoted a lengthy chapter to "Thought and Literature in Canada,." Collins lost no time in dethroning what had been English Canada's top poets, the 'three Charleses': Charles Heavysege, Charles Sangster, and Charles Mair. "Collins allots Heavysege only one paragraph, dismisses Sangster’s verse as 'not worth a brass farthing,' and ignores Mair completely." In contrast, Collins devoted fifteen pages to Roberts. " more than anyone else, Edmund Collins is probably responsible for the early acceptance of Charles G.D. Roberts as Canada’s foremost poet."[16]

In Songs of the Great Dominion (1889), anthologist W.D. Lighthall pronounced that "The foremost name in Canadian song at the present day is that of Charles George Douglas Roberts." Lighthall included poetry by Roberts (who had published two books by then), by Lampman, Campbell, and F.G. Scott (one book each), and also by Carman and D.C. Scott, although neither had published a book at that time.[16]

"The publication in 1893 of a little anthology called Later Canadian Poems, edited by J.E. Wetherell, was a defining event in bringing attention to the Confederation Poets as a group."[16] The 'three Charleses' are gone: Roberts, Lampman, Carman, Campbell, the Scotts, and George Frederick Cameron are the male poets represented. That would be the pattern repeated in subsequent anthologies, with minor variations: like A Treasury of Canadian Verse (1900), which Campbell boycotted; or The Oxford Book of Canadian Verse (1913), which Campbell edited, and "devoted more pages to his own poetry than that of anyone else."[16]

The same poets were included in the books on Canadian literature that began appearing in the new century: Archibald MacMurchy’s Handbook of Canadian Literature (1906), followed by T.G. Marquis's English Canadian Literature (1913). "The decade following the First World War saw the appearance of five more handbooks on Canadian literature.... As different as these five books are from each other, they all recognize the accomplishments of the Confederation Poets as an important advance in Canadian literature."[16]

Debunking

As the canon, the Confederation Poets set the standard. Their work became the type of poetry Canadian readers wanted and expected, and therefore Canadian magazines published. Since that standard was Romantic and Victorian, the Confederation Poets were blamed by some for retarding the development of Modernist poetry in Canada. For example, the Twentieth-Century Literary Movements Dictionary says of them that: "Their legacy of Realism, Romanticism, and nationalism was so powerful that it lasted well into the first decades of the 20th century, beyond when much of their best work had been published," according to the .[6]

Certainly that was a complaint of the Montreal Group or McGill Movement, "a group of young intellectuals under the influence of Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot.... In Montreal the assault was spearheaded by The McGill Fortnightly Review (1925-1927), edited chiefly by two graduate students, A.J.M. Smith and F. R. Scott (son of Frederick George Scott)."[16] "In various editorials, Smith argued that Canadian poets must go beyond the ‘maple-leaf school’ of Bliss Carman, Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott, and Charles G.D. Roberts in favour of free verse, imagistic treatment, displacement, complexity, and a leaner diction free of Victorian mannerisms."[17] The intentionally disparaging term “Maple Leaf School” was picked up from the progressive magazine Canadian Forum, which was waging a similar crusade for literary modernism.[16]

"Probably the most resounding salvo by the Canadian Modernists is F. R. Scott’s 'The Canadian Authors Meet,' the first draft of which appeared in The McGill Fortnightly in 1927. One of its six stanzas lampooned the attention given to the Confederation Poets":[16]

- The air is heavy with Canadian topics,

- And Carman, Lampman, Roberts, Campbell, Scott,

- Are measured for their faith and philanthropics,

- Their zeal for God and King, their earnest thought.

However, such complaints ignore that modernist poetry was being written in the 1920s: by W.W.E. Ross, Dorothy Livesay, Raymond Knister, and even a couple of the Confederation Poets themselves. By the 1930s Roberts had begun introducing the themes and techniques of Modernist poetry into his work.[6] (See, for example, "The Iceberg" from 1931.) Scott had been doing the same since the early 1920s. (See, for example, "A Vision" from 1921.)

After he had won a reputation as an anthologist of Canadian poetry (The Book of Canadian Poetry 1943, Modern Canadian Verse 1967), Smith changed his opinion of the Confederation Poets' work, blaming his earlier disparagement on youthful ignorance: "Bliss Carman was the only Canadian poet that we had heard of and what we heard, we didn't care for much. It was only later, when I began to compile books on Canadian poetry, that I found that Lampman, Roberts and Carman had written some very fine poetry."[18]

Re-evaluation

The rehabilitation of the Confederation writers began with a rise of Canadian nationalism during the late 1950s, in what has been called "a cultural moment inspired by the founding of the Canada Council (1957), and the establishment of the New Canadian Library, with [Malcolm] Ross himself as general editor." Ross's Poets of the Confederation rolled off the press as New Canadian Library Original N01. "As Hans Hauge puts it, Ross ‘is beginning to construct a national literature and he does so by providing it with a past, that is to say, by projecting the project of a Canadian national literature into the past’ (‘The invention of national literatures’, in Literary responses to Arctic Canada, ed. Jørn Carlsen, 1993)."[5]

Ross's claim was that his four Confederation Poets were Canadians who "were poets – at their best, good poets." "Here, at least, was skill, the possession of the craft, the mystery. Here was another – one like oneself. Here was something stirring, something in a book by one of ourselves,' something as alive and wonderful in its own way as the [achievements] of the railway builders. Our empty landscape of the mind was being peopled at last."[1]

Ross de-emphasized, but did not question, the modernist debunking of the Confederation Poets: "It is natural enough that our recent writers have abandoned and disparaged 'The Maple Leaf School' of Canadian poetry. Fashions have changed. Techniques have changed."[1]

Indeed, fashions and techniques do change; and by the mid-1980s the modernist presumptions behind the Montreal Group's debunking were themselves being questioned. "A proper recognition of his nineteenth-century contexts can enhance our appreciation of Carman, and of his Confederation peers," Tracy Ware wrote in Canadian Poetry in 1984 "I am suggesting that Confederation poetry be given the respect that is customarily accorded the poetry of the McGill movement. Such a critical approach might succeed in removing the pervasive but dubious anti-Romantic tenets of Canadian modernism, tenets that have lingered here long after they have been questioned elsewhere."[19]

In the same issue, Canadian Poetry editor D.M.R. Bentley, using Lampman's term for himself, dubbed the Confederation school "Minor Poets of a Superior Order," and argued that "What James Reaney has recently written of Crawford, Lampman and Roberts can be extended to Carman, Scott, Campbell, Sherman, Pickthall and others: they 'wrote well and were of note.'"[20]

References

- 1 2 3 Malcolm Ross, Introduction, Poets of the Confederation (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1960), vii-xii.

- ↑ "Confederation Poets," Canadian Poetry, UWO.ca. Web, Mar. 21, 2011.

- ↑ Tony Tremblay, "John Medley," New Brunswick Literary Encyclopedia, STU, Web, Apr. 17 2011.

- ↑ "Secondary Confederation Poets," PoetsPathway.ca, Web, Apr. 17, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Francis Zichy, "Confederation Poets," Encyclopedia of Literature, JRank.org. Web, Mar. 20, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Article, "Confederation Poets: Canada, 1880s-1920s", in Henderson, Helene, and Jay P. Pederson, editors, Twentieth-Century Literary Movements Dictionary (Detroit: Omnigraphics Inc., 2000), 84-85.

- ↑ W.J. Keith, "Poetry in English 1867-1918," Canadian Encyclopedia (Edmonton: Hurtig, 1988), 1696.

- ↑ "Archibald Lampman 1891," Colombo's All-Time Great Canadian Quotations, Highbeam.com, Web, Mar. 28, 2011.

- ↑ At the Mermaid Inn’

- ↑ John Coldwell Adams, "William Wilfred Campbell," Confederation Voices: Seven Canadian Poets, Canadian Poetry, UWO. Web, Mar. 21, 2011.

- ↑ John Coldwell Adams, "Duncan Campbell Scott," Confederation Voices, Canadian Poetry, UWO, Web, Mar. 30, 2011.

- 1 2 "Campbell, William Wilfred," Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. Web, Mar. 20, 2011.

- ↑ Ken Norris, "The Beginnings of Canadian Modernism," Canadian Poetry: Studies/Documents/Reviews," No. 11 (Fall/Winter, 1982), UWO. Web, Mar. 25, 2011.

- 1 2 Northrop Frye, "from 'Letters in Canada' 1954," The Bush Garden (Toronto: Anansi, 1971), 34.

- ↑ "Confederation Poets," Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, Answers.com, Web, Apr. 7, 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 John Coldwell Adams, "The Whirligig of Time," Confederation Voices, Canadian Poetry, UWO.ca, Web, Mar. 28, 2011.

- ↑ Geoff Hancock, "McGill Fortnightly Review - (1925 – 7)," Encyclopedia of Literature, JRank.org. Web, Mar. 25, 2011.

- ↑ Anne Burke, Critical Introduction, "Some Annotated Letters of A.J.M. Smith and Raymond Knister," Canadian Poetry: Studies/Documents/Reviews, Number 11 (Fall/Winter 1982), UWO, Web, Mar. 26, 2011.

- ↑ Tracy Ware, "The Integrity of Carman’s 'Low Tide on Grand Pré'," Canadian Poetry: Studies/Documents/Reviews No. 14, UWO, Web, Apr. 16, 2011.

- ↑ D.M.R. Bentley, "Preface: Minor Poets of a Superior Order," Canadian Poetry: Studies/Documents/Reviews No. 14, UWO, Web, Apr. 16, 2011.

Further reading

- D.M.R. Bentley, The Confederation Group of Canadian Poets, 1880-1897, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division. 2004

External links

- The Confederation Poets at the Canadian Poetry Press website

- Poets of the Confederation: Current Approaches Canadian Poetry: Studies/Documents/Reviews No. 14 (Spring/Summer 1984)

- The Confederation Poets at The Poets’ Pathway Committee website

.jpg)