Court system of Canada

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Canada |

| Government |

|

|

Related topics |

The court system of Canada forms the judicial branch of government, formally known as "the Queen on the Bench",[1] which interprets the law and is made up of many courts differing in levels of legal superiority and separated by jurisdiction. Some of the courts are federal in nature while others are provincial or territorial.

The Canadian constitution gives the federal government the exclusive right to legislate criminal law while the provinces have exclusive control over civil law. The provinces have jurisdiction over the administration of justice in their territory. Almost all cases, whether criminal or civil, start in provincial courts and may be eventually appealed to higher level courts. The quite small system of federal courts only hears cases concerned with matters which are under exclusive federal control, such as federal taxation, federal administrative agencies, intellectual property, some portions of competition law and certain aspects of national security. The federal government appoints and pays for both the judges of the federal courts and the judges of the superior and appellate level courts of each province. The provincial governments are responsible for appointing judges of the lower provincial courts. Provincial administrative tribunals also comprise part of provincial courts. This intricate interweaving of federal and provincial powers is typical of the Canadian constitution.

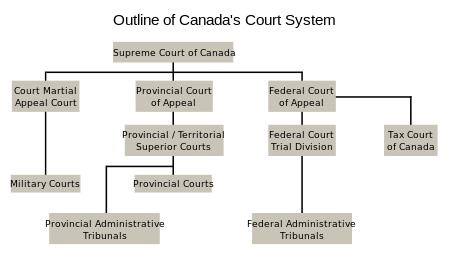

Outline of the court system

Very generally speaking, Canada's court system is a four-level hierarchy as shown below from highest to lowest in terms of legal authority. Each court is bound by the rulings of the courts above them; however, they are not bound by the rulings of other courts at the same level in the hierarchy. Civil courts in Quebec, in particular, are under no obligation to apply judicial precedent—the principle of stare decisis—which is the general rule elsewhere in Canada. This is because Quebec's civil law is entirely codified, while civil law in the other nine provinces grew out of the English common law.

A note on terminology

There are two terms used in describing the Canadian court structure which can be confusing, and clear definitions are useful at the outset.

Provincial courts

The first is the term "provincial court," which has two quite different meanings, depending on context. The first, and most general meaning, is that a provincial court is a court established by the Legislature of a province, under its constitutional authority over the Administration of Justice in the Province, set out in s. 92(14) of the Constitution Act, 1867.[2] This head of power gives the Provinces the power to regulate "... the Constitution, Maintenance, and Organization of Provincial Courts, both of Civil and of Criminal Jurisdiction, and including Procedure in Civil Matters in those Courts." All courts created by a Province, from the small claims court or municipal by-law court, up to the provincial Court of Appeal, are "provincial courts" in this general sense.

However, there is a more limited meaning to the term. In most provinces, the "Provincial Court" is the term used to refer to a specific court created by the Province which is the main criminal court, having jurisdiction over most criminal offences except for the most serious ones. The Provincial Court of a particular province may also have a limited civil jurisdiction, over small claims and some family law matters. The exact scope of the jurisdiction of a Provincial Court will depend on the laws enacted by the particular province. Provincial Courts in this sense are courts of limited statutory jurisdiction, sometimes referred to as "inferior courts." As courts of limited jurisdiction, their decisions are potentially subject to judicial review by the superior courts via the prerogative writs, but in most cases there are now well-established statutory rights of appeal instead.

To distinguish between the two meanings of the term, capitalization is used. A reference to a "provincial court" normally is a reference to the broad meaning of the term, any court created by the Province. A reference to "Provincial Court" normally is referring to the specific court of limited statutory jurisdiction, created by the Province.

Superior courts

The second is the term "superior courts." This term also has two different meanings, one general and one specific.

The general meaning is that a superior court is a court of inherent jurisdiction. Historically, they are the descendants of the royal superior courts in England. The decisions of a superior court are not subject to review, unless a statute specifically provides for review or appeal. The term is not limited to trial courts. The Federal Court of Appeal and the provincial and territorial Courts of Appeal are all superior courts.

The more limited sense is that "Superior Court" can be used to refer to the superior trial court of original jurisdiction in the Province. This terminology is used in the court systems of Ontario and Quebec.

The difference between the two terms is also indicated by capitalisation. The term "superior court" is used to mean the general sense of the term, while "Superior Court" is used to refer to specific courts in provinces which use that term to designate their superior trial courts.

Supreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court is established by the Supreme Court Act[3] as the "General Court of Appeal for Canada." The Court currently consists of nine justices, which include the Chief Justice of Canada and eight puisne justices. The court's duties include hearing appeals of decisions from the appellate courts (to be discussed next) and, on occasion, delivering references (i.e., the court's opinion) on constitutional questions raised by the federal government. By law, three of the nine justices are appointed from Quebec because of Quebec's use of civil law.

The Constitution Act, 1867 gives the federal Parliament the power to create a "General Court of Appeal for Canada."[4] Following Confederation, the Conservative government of Sir John A. Macdonald proposed the creation of a Supreme Court and introduced two bills in successive sessions of Parliament to trigger public debate on the proposed court and its powers.[5] Eventually, in 1875, the Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie passed an Act of Parliament which established the Supreme Court.[6] The 1875 Act built upon the proposals introduced by the Macdonald government, and passed with bipartisan support.[7]

Initially, decisions of the Supreme Court could be appealed to the Judicial Committee of the British Privy Council. As well, litigants could appeal directly from the provincial courts of appeal directly to the Judicial Committee, by-passing the Supreme Court entirely. There was a provision in the 1875 Act which attempted to limit appeals to the Judicial Committee. That clause resulted in the Governor General reserving the bill for consideration by the Queen-in-Council.[8] After much debate between Canadian and British officials, royal assent was granted, on the understanding that the clause did not in fact affect the royal prerogative to hear appeals, exercised through the Judicial Committee.[9] The question of the power of Parliament to abolish appeals to the Judicial Committee eventually was tested in the courts. In 1926, the Judicial Committee ruled that the Canadian Parliament lacked the jurisdiction to extinguish appeals to the Judicial Committee, as the right of appeal was founded in the royal prerogative and could only be terminated by the Imperial Parliament.[10] Following the enactment of the Statute of Westminster, in 1933 the federal Parliament passed legislation again abolishing the right of appeal in criminal matters. In 1935, the Judicial Committee upheld the constitutional validity of that amendment.[11] In 1939, the federal government proposed a reference to the Supreme Court of Canada, asking whether the federal Parliament could terminate all appeals to the Judicial Committee. By a 4-2 decision, the Supreme Court held that the proposal was within the powers of the federal Parliament and would be constitutional.[12] The question was then appealed to the Judicial Committee, but the hearing of the appeal was delayed by the outbreak of World War II.[13] in 1946, the Judicial Committee finally heard the appeal and upheld the decision of the majority of the Supreme Court,[14] clearing the way for Parliament to enact legislation to end all appeals to the Judicial Committee, whether from the Supreme Court or from the provincial courts of appeal. In 1949, Parliament passed an amendment to the Supreme Court Act which abolished all appeals, making the Court truly the Supreme Court.[15] However, cases which had been instituted in the lower courts prior to the amendment could still be appealed to the Judicial Committee. The last Canadian appeal to the Judicial Committee was not decided until 1960.[16]

Appellate courts of the provinces and territories

These courts of appeal (as listed below by province and territory in alphabetical order) exist at the provincial and territorial levels and were separately constituted in the early decades of the 20th century, replacing the former Full Courts of the old Supreme Courts of the provinces, many of which were then renamed Courts of Queens Bench. Their function is to review decisions rendered by the superior-level courts and to deliver references when requested by a provincial or territorial government as the Supreme Court does for the federal government. These appellate courts do not normally conduct trials or hear witnesses.

- Court of Appeal of Alberta (ABCA)[17]

- Court of Appeal of British Columbia (BCCA)[18]

- Manitoba Court of Appeal (MBCA)[19]

- Court of Appeal of New Brunswick (NBCA)[20]

- Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador (Court of Appeal) (NLCA)[21]

- Court of Appeal for the Northwest Territories (NTCA)[22]

- Nova Scotia Court of Appeal (NSCA)[23]

- Nunavut Court of Appeal (NUCA)[24]

- Court of Appeal for Ontario (ONCA)[25]

- Prince Edward Island Court of Appeal (PECA)[26]

- Québec Court of Appeal (QCCA)[27]

- Court of Appeal for Saskatchewan (SKCA)[28]

- Court of Appeal of Yukon (YKCA)[29]

These courts are Canada's equivalent of the Court of Appeal in England and the various State Supreme Courts and U.S. Courts of Appeals in the United States. Each of the above-listed appellate courts is the highest court from its respective province or territory. Each province's chief justice sits in the appellate court of that province.

Superior-level courts of the provinces and territories

These courts (as listed below by province and territory in alphabetical order) exist at the provincial and territorial levels. The superior courts are the courts of first instance for divorce petitions, civil lawsuits involving claims greater than small claims, and criminal prosecutions for indictable offences (i.e., felonies in American legal terminology). They also perform a reviewing function for judgements from the local inferior courts and administrative decisions by provincial or territorial government entities such as labour boards, human rights tribunals and licensing authorities.

- Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta (ABQB)

- Supreme Court of British Columbia (BCSC)

- Court of Queen's Bench of Manitoba (MBQB)

- Court of Queen's Bench of New Brunswick (NBQB)

- Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador (Trial Division) (NLTD)

- Supreme Court of the Northwest Territories (NTSC)[30]

- Supreme Court of Nova Scotia (NSSC)

- Nunavut Court of Justice (NUCJ)[31]

- Court of Ontario – Ontario Superior Court of Justice (ONSC)

- Supreme Court of Prince Edward Island (PESC)

- Québec Superior Court (QCCS)

- Court of Queen's Bench for Saskatchewan (SKQB)

- Supreme Court of Yukon (YKSC)[32]

Furthermore, some of these superior courts (like the one in Ontario) have specialized branches that deal only with certain matters such as family law or small claims. To complicate things further, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice has a branch called the Divisional Court that hears only appeals and judicial reviews of administrative tribunals and whose decisions have greater binding authority than those from the "regular" branch of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice. Although a court, like the Supreme Court of British Columbia, may have the word "supreme" in its name, it is not necessarily the highest court in its respective province or territory.

Most provinces have special courts dealing with small claims (lawsuits for less than a certain amount of money). These are typically divisions of the superior courts in each province. Parties often represent themselves, without lawyers, in these courts.

Provincial and territorial ("inferior") courts

Each province and territory in Canada has an "inferior" or "lower" trial court, usually called a Provincial (or Territorial) Court, to hear certain types of cases.

- Provincial Court of Alberta (ABPC)

- Provincial Court of British Columbia (BCPC)

- Provincial Court of Manitoba (MBPC)

- Provincial Court of New Brunswick (NBPC)

- Provincial Court of Newfoundland and Labrador (NLPC)

- Territorial Court of the Northwest Territories (NTTC)

- Provincial Court of Nova Scotia (NSPC)

- Nunavut Court of Justice (NUCJ)

- Court of Ontario – Ontario Court of Justice (ONCJ)

- Provincial Court of Prince Edward Island (PEPC)

- Court of Québec (QCCQ)

- Provincial Court of Saskatchewan (SKPC)

- Territorial Court of Yukon (YKTC)

Appeals from these courts are heard either by the superior court of the province or territory or by the Court of Appeal. In criminal cases, this depends on the seriousness of the offence. These courts are created by provincial statute and only have the jurisdiction granted by statute. Accordingly, inferior courts do not have inherent jurisdiction. These courts are usually the successors of older local courts presided over by lay magistrates and justices of the peace who did not necessarily have formal legal training. However, today all judges are legally trained, although justices of the peace may not be. Many inferior courts have specialized functions, such as hearing only criminal law matters, youth matters, family law matters, small claims matters, "quasi-criminal" offences (i.e., violations of provincial statutes), or bylaw infractions. In some jurisdictions these courts serve as an appeal division from the decisions of administrative tribunals.

Federal courts

In addition to the Supreme Court of Canada, there are three civil courts created by the federal Parliament under its legislative authority under s. 101 of the Constitution Act, 1867:

Federal Court of Appeal

The Federal Court of Appeal hears appeals from decisions rendered by the Federal Court, the Tax Court of Canada and a certain group of federal administrative tribunals like the National Energy Board and the federal labour board. All judges of the Federal Court are ex officio judges of the Federal Court of Appeal, and vice versa, although it is rare that a judge of one court will sit as a member of the other.

Federal Court

The Federal Court exists primarily to review administrative decisions by federal government bodies such as the immigration board and to hear lawsuits under the federal government's jurisdiction such as intellectual property and maritime law. It also has concurrent jurisdiction with the superior trial courts of the Provinces to hear civil lawsuits brought against the federal government. The Federal Court also has jurisdiction to determine inter-jurisidctional legal actions between the federal government and a provinces, or between different provinces, provided the province in question has passed corresponding legislation granting the Federal Court jurisdiction over the dispute.

In the aftermath of 9/11, Parliament enacted a number of laws to protect national security. The Federal Court has exclusive jurisdiction to determine many issues which arise under those laws relating to national security.

Appeals lie from the Federal Court to the Federal Court of Appeal.

Tax Court of Canada

The Tax Court of Canada has a very specialised jurisdiction. It hears disputes over federal taxes, primarily under the federal Income Tax Act, between taxpayers and the federal government. Appeals lie from the Tax Court to the Federal Court of Appeal.

History of the federal courts

The first federal court was the Exchequer Court of Canada, created in 1875 at the same time as the Supreme Court of Canada.[6] The Exchequer Court was a trial court, with a limited jurisdiction over civil actions brought against the federal government, tax disputes under federal tax laws, admiralty matters, compensation for expropriation of private property by the federal Crown, negligence of federal public servants, and intellectual property, including patents and copyright. The name of the court came from the Exchequer Court of England, which had a similar jurisdiction over tax disputes. At first, there were no separate judges for the Exchequer Court. The judges of the Supreme Court of Canada were also appointed to the Exchequer Court. Individual judges of the Supreme Court would sit as a judge of the Exchequer Court, with an appeal lying to the Supreme Court. The Exchequer Court did not have any jurisdiction to review the actions of federal administrative agencies. That function was fulfilled by the provincial superior trial courts.

In 1971, Parliament passed the Federal Court Act[33] which abolished the Exchequer Court and created a new court, the Federal Court of Canada. That Court had two divisions: the Federal Court - Trial Division, and the Federal Court - Appeal Division. Although the two divisions had different functions, they were all part of a single court.

In 2003, Parliament passed legislation which divided the Federal Court into two courts. The Federal Court - Trial Division became the Federal Court of Canada, while the Federal Court - Appeal Division became the Federal Court of Appeal. The jurisdiction of the two new courts is essentially the same as the corresponding former divisions of the Federal Court.

Although the federal courts can be said to have the same prestige as the superior courts from the provinces and territories, they lack the "inherent jurisdiction" (to be explained later) possessed by superior courts such as the Ontario Superior Court of Justice.

Military courts

- Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada

- Various military courts called courts martial:

- General Court Martial

- Standing Court Martial

- Summary Trial hearings

The courts martial are conducted and presided over by military personnel and exist for the prosecution of military personnel, as well as civilian personnel who accompany military personnel, accused of violating the Code of Service Discipline, which is found in the National Defence Act (R.S.C. 1985, Chapter N-5) and constitutes a complete code of military law applicable to persons under military jurisdiction.

The decisions of the courts martial can be appealed to the Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada which, in contrast, exists outside the military and is made up of civilian judges. This appellate court is the successor of the Court Martial Appeal Board which was created in 1950, presided over by civilian judges and lawyers, and was the first ever civilian-based adjudicating body with authority to review decisions by a military court. The Court Martial Appeal Court is made up of civilian judges from the Federal Court, Federal Court of Appeal, and the superior courts of the provinces.

Summary trials are ad hoc hearings used to dispense with minor service offenses. The Presiding Officer will have little formal legal training and is generally the service member's Commanding Officer. In this respect, these hearings are similar to the former lay magistrates' courts.

Federal and provincial administrative tribunals

Known in Canada as simply "tribunals", these are quasi-judicial adjudicative bodies, which means that they adjudicate (hear evidence and render decisions) like courts, but are not necessarily presided over by judges. Instead, the adjudicators may be experts of the very specific legal field handled by the tribunal (e.g., labour law, human rights law (known in the US as "civil rights law"), immigration law, energy law, workers' compensation law, liquor licensing law, etc.) who hear arguments and evidence provided by lawyers (also lay advocates in British Columbia) before making a written decision on record.

Depending on its enabling legislation, a tribunal's decisions may be reviewed by a court through an appeal or a process called judicial review. The reviewing court may be required to show some deference to the tribunal if the tribunal possesses some highly specialized expertise or knowledge that the court does not have. The degree of deference will also depend on such factors as the specific wording of the legislation creating the tribunal. Tribunals whose enabling legislation contains a privative clause are entitled to a high degree of deference, although a recent decision of the Supreme Court of Canada (Dunsmuir v. New Brunswick, 2008 SCC 9) has arguably lowered that degree of deference.

Tribunals which have the power to decide questions of law may take into consideration the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which is part of Canada's constitution. The extent to which tribunals may use the Charter in their decisions is a source of ongoing legal debate.

Appearing before some administrative tribunals may feel like appearing in court, but the tribunal's procedure is relatively less formal than that of a court, and more importantly, the rules of evidence are not as strictly observed, so that some evidence that would be inadmissible in a court hearing may be allowed in a tribunal hearing, if relevant to the proceeding. While relevant evidence is admissible, evidence which the adjudicator determines to have questionable reliability, or is otherwise questionable, is most likely to be afforded little or no weight.

The presiding adjudicator is normally called "Mister/Madam Chair". As is the case in court, lawyers routinely appear in tribunals advocating matters for their clients. A person does not require a lawyer to appear before an administrative tribunal. Indeed, many of these tribunals are specifically designed to be more representative to unrepresented litigants than courts. Furthermore, some of these tribunals are part of a comprehensive dispute-resolution system, which may emphasize mediation rather than litigation. For example, provincial human rights commissions routinely use mediation to resolve many human rights complaints without the need for a hearing.

What tribunals all have in common is that they are created by statute, their adjudicators are usually appointed by government, and they focus on very particular and specialized areas of law. Because some subject matters (e.g., immigration) fall within federal jurisdiction while others (e.g., liquor licensing and workers' compensation) in provincial jurisdiction, some tribunals are created by federal law while others are created by provincial law. There are both federal and provincial tribunals for some subject matters such as unionized labour and human rights.

Most importantly, from a lawyer's perspective, is the fact that the principle of stare decisis does not apply to tribunals. In other words, a tribunal adjudicator could legally make a decision that differs from a past decision, on the same subject and issues, delivered by the highest court in the land. Because a tribunal is not bound by legal precedent, established by itself or by a reviewing court, a tribunal is not a court even though it performs an important adjudicative function and contributes to the development of law like a court would do.

Although stare decisis does not apply to tribunals, their adjudicators will likely nonetheless find a prior court decision on a similar subject to be highly persuasive and will likely follow the courts in order to ensure consistency in the law and to prevent the embarrassment of having their decisions overturned by the courts. The same is true for past decisions of the tribunal.

Among the federal tribunals, there is a small group of tribunals whose decisions must be appealed directly to the Federal Court of Appeal rather than to the Federal Court Trial Division. These so-called "super tribunals" are listed in Subsection 28(1) of the Federal Court Act (R.S.C. 1985, Chapter F-7) and some examples include the National Energy Board, Canadian International Trade Tribunal, the Competition Tribunal, the Canada Industrial Relations Board (i.e. federal labour board), the Copyright Board, and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission ("CRTC").

Courts of inherent jurisdiction

The superior courts from the provinces and territories are courts of inherent jurisdiction, which means that the jurisdiction of the superior courts is more than just what is conferred by statute. Following the principles of English common law, because the superior courts derive their authority from the Constitution, they can hear any matter unless there is a federal or provincial statute that says otherwise or that gives exclusive jurisdiction to some other court or tribunal. The doctrine of inherent jurisdiction gives superior courts greater freedom than statutory courts to be flexible and creative in the delivering of legal remedies and relief.

Statutory courts

The Supreme Court of Canada, the federal courts, the various appellate courts from the provinces and territories, and the numerous low-level provincial courts are statutory courts whose decision-making power is granted by either the federal parliament or a provincial legislature.

The word "statutory" refers to the fact that these courts' powers are derived from a statute and is defined and limited by the terms of the statute. A statutory court cannot try cases in areas of law that are not mentioned or suggested in the statute. In this sense, statutory courts are similar to non-judicial adjudicative bodies such as administrative tribunals, boards, and commissions, which are created and given limited power by legislation. The practical implication of this is that a statutory court cannot provide a type of legal remedy or relief that is not expressly or implicitly referred to in its enabling or empowering statute.

Appointment and regulation of judges

Judges in Canada are appointed and not elected. Judges of the Supreme Court of Canada, the federal courts, the appellate courts and the superior-level courts are appointed by the Governor-in-Council (by the Governor General on the advice of the Federal Cabinet).[34] Thus, judges of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice are chosen not by Ontario's provincial government but upon the recommendations of Her Majesty's Canadian Government. Meanwhile, judicial appointments to judicial posts in the so-called "inferior" or "provincial" courts are made by the local provincial governments.

As judicial independence is seen by Canadian law to be essential to a functioning democracy, the regulating of Canadian judges requires the involvement of the judges themselves. The Canadian Judicial Council, made up of the chief justices and associate chief justices of the federal courts and of each province and territory, receive complaints from the public concerning questionable behaviour from members of the bench.

Salaries of superior courts are set by Parliament under section 100 of the Constitution Act, 1867. Since the Provincial Judges Reference of 1997, provincial courts' salaries are recommended by independent commissions, and a similar body called the Judicial Compensation and Benefits Commission was established in 1999 for federally appointed judges.

Tenure of judges and removal from the bench

Judges in positions that are under federal control (federally appointed positions) are eligible to serve on the bench until age 75. In some but not all Provincial and Territorial positions, appointed judges have tenure until age 70 instead.

As for removal from the bench, judges have only rarely been removed from the bench in Canada. For federally appointed judges, it is the task of The Canadian Judicial Council to investigate complaints and allegations of misconduct on the part of federally appointed judges. The Council may recommend to the (federal) Minister of Justice that the judge be removed. To do so, the Minister must in turn get the approval of both the House of Commons and the Senate before a judge can be removed from office. (The rules for provincial/territorial judges are similar, but they can be removed by a provincial or territorial cabinet.)[35]

Languages used in court

English and French are both official languages of the federal government of Canada. Either official language may be used by any person or in any pleading or process in or issuing from any Court of Canada established by Parliament under the Constitution Act, 1867.[36] This constitutional guarantee applies to the Supreme Court of Canada, the Federal Court of Appeal, the Federal Court, the Tax Court of Canada, and the Court Martial Appeal Court. Parliament has expanded on that constitutional guarantee to ensure that the federal courts are institutionally bilingual.[37]

The right to use either language in the provincial and territorial courts varies. The Constitution guarantees the right to use either French or English in the courts of Quebec[38] and New Brunswick.[39] There is a statutory right to use either English or French in the courts of Ontario[40] and Saskatchewan,[41] and a limited right to use French in oral submissions in the courts of Alberta.[42]

As well, in all criminal trials under the Criminal Code, a federal statute, every accused whose language is either English or French has the right to be tried in the language of their choice.[43] As a result, every court of criminal jurisdiction in Canada, whether federal, provincial or territorial, must have the institutional capacity to provide trials in either language.

Furthermore, under section 14 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms a party or witness in any proceedings who does not understand or speak the language in which the proceedings are conducted or who is deaf has the right to the assistance of an interpreter.

In the Northwest Territories[44] and Nunavut[45] the official aboriginal languages may be used as well.

Court customs

Courtroom custom is largely based upon the British tradition, with a few modifications.

Symbols

Canadian courts derive their authority from the monarch. Consequently, the judicial system in Canada is formally known as the "The Queen on the Bench".[1] As a result, important symbols in a courtroom include the picture of the Canadian monarch and their heraldic Arms, although not all courtrooms have a picture of the monarch. Many courts display Canadian and provincial flags. In the British Columbia courts as well as in the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador, the Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom is displayed for reasons of tradition.

Dress

In superior courts, lawyers wear black robes and white neck tabs, like barristers in the United Kingdom, but they do not wear wigs. Business attire is appropriate when appearing before judges of superior courts sitting in chambers and before judges of provincial or territorial courts or justices of the peace.

Judges dress in barrister's robes similar to the lawyers'. Judges of some courts adorn their robes with coloured sashes. For example, Federal Court Judges' robes are adorned with a gold sash, and Tax Court of Canada Judges' robes with a purple sash.

Etiquette/Decorum

- Judges do not use gavels. Instead, a judge raises his or her voice (or stands up if necessary) to restore order in the courtroom.

- In most jurisdictions, when entering or leaving a courtroom when there is a judge seated inside, one should bow, while standing inside the court but near the doorway, in the direction of the seated judge. Many lawyers also bow when crossing the bar.

- Judges of superior courts in some provinces are traditionally addressed as "My Lord" or "My Lady," but in other provinces are referred to as "Your Honour". Judges of inferior courts are always traditionally referred to in person as "Your Honour". The practice varies across jurisdictions, with some superior court judges preferring the titles "Mister Justice" or "Madam Justice" to "Lordship".[46] Judges of the Supreme Court of Canada and of the federal-level courts prefer the use of "Mister/Madam (Chief) Justice". Justices of the Peace are addressed as "Your Worship".

- Judges of inferior courts are referred to as "Judge [Surname]" while judges of superior and federal courts are referred to as "Mister/Madam Justice [Surname]," except in Ontario, where all trial judges in referred to as "Mister/Madam Justice".

- A lawyer advocating in court typically uses "I" when referring to him or herself. The word "we" is not used, even if the lawyer is referring to him/herself and his/her client as a group.

- The judge in court refers to a lawyer as "counsel" (not "counsellor"), or simply "Mr./Ms. [surname]". In Quebec, the title "Maître" is used.

- In court, it is customary for opposing counsel to refer to one another as "my friend", or sometimes (usually in the case of Queen's Counsel) "my learned friend".

- In any criminal law case, the prosecuting party is "the Crown" while the criminally prosecuted person is called the "accused" (not the "defendant"). The prosecuting lawyer is called "Crown Counsel" (or, in Ontario, "Crown attorney"). Crown counsel in criminal proceedings are customarily addressed and referred to as "Mr Crown" or "Madam Crown."

- The "versus" or "v." in the style of cause of Canadian court cases is often pronounced "and" (rather than "vee" or "versus" as in the US or "against" in criminal proceedings in England, Scotland, and Australasia). For example, Roncarelli v. Duplessis would be pronounced "Roncarelli and Duplessis".

Procedure

- The judicial function of the Royal Prerogative is performed in trust and in the Queen's name by officers of Her Majesty's court, who enjoy the privilege granted conditionally by the sovereign to be free from criminal and civil liability for unsworn statements made within the court.[47] This dispensation extends from the notion in common law that the sovereign "can do no wrong".

- There are no so-called "sidebars" where lawyers from both sides approach the bench in order to have a quiet and discreet conversation with the judge while court is in session.

- Trial judges typically take a passive role during trial; however, during their charge to the jury, judges may comment upon the value of certain testimony or suggest the appropriate amount of damages in a civil case, although they are required to tell the jury that it is to make its own decision and is not bound to agree with the judge.

- Jury trials are less frequent than in the United States and usually reserved for serious criminal cases. A person accused of a crime punishable by imprisonment for five years or more has the constitutional right to a jury trial. Only British Columbia and Ontario regularly use juries in civil trials.

- Evidence and documents are not passed directly to the judge, but instead passed to the judge through the court clerk. The clerk, referred to as "Mister/Madam Clerk" or "Mister/Madam Registrar", also wears a robe and sits in front of the judge and faces the lawyers.

- In some jurisdictions, the client sits with the general public, behind counsel's table, rather than beside his or her lawyer at counsel's table. The accused in a criminal trial sits in the prisoners box often located on the side wall opposite the jury, or in the middle of the courtroom. However it is becoming increasingly common for accused persons to sit at counsel table with their lawyers.

- In four provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario), the superior-level courts employ judicial officers known as Masters who deal only with interlocutory motions (or interlocutory applications) in civil cases. With such Masters dealing with the relatively short interlocutory motion/application hearings, trial judges can devote more time on more lengthy hearings such as trials. In the Federal Court, a Prothonotary holds a similar positions to that of a Master.

See also

References

- 1 2 MacLeod, Kevin S. (2008), A Crown of Maples (PDF) (1 ed.), Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada, p. 17, ISBN 978-0-662-46012-1, retrieved 19 January 2015

- ↑ Constitution Act, 1867, s. 92(14)

- ↑ Supreme Court Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. S-26

- ↑ Constitution Act, 1867, s. 101

- ↑ Snell and Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada - History of the Institution (Toronto: Osgoode Society, 1985), pp. 6-7.l

- 1 2 The Supreme and Exchequer Courts Act, S.C. 1875, c. 11.

- ↑ Snell and Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada - History of the Institution, pp. 10-11

- ↑ Snell and Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada - History of the Institution, p. 16.

- ↑ Snell and Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada - History of the Institution, pp. 178-179.

- ↑ Nadan v. The King, [1926] A.C. 482 (P.C.)

- ↑ British Coal Corporation v. The King, [1935] A.C. 500 (P.C.).

- ↑ Reference re Supreme Court Act Amendment Act, [1940] S.C.R. 49.

- ↑ Snell and Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada - History of the Institution, p. 188.

- ↑ Reference re Privy Council Appeals, [1947] A.C. 127.

- ↑ An Act to Amend the Supreme Court Act, S.C. 1949, c. 37.

- ↑ Ponoka-Calmar Oils v Wakefield, [1960] A.C. 18 (P.C.).

- ↑ Court of Appeal Act, R.S.A. 2000, c. C-30

- ↑ Court of Appeal Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 77

- ↑ The Court of Appeal Act, C.C.S.M., c. C240

- ↑ Judicature Act, R.S.N.B. 1973, c. J-2

- ↑ Judicature Act, R.S.N.L. 1990, c. J-4

- ↑ Judicature Act, R.S.N.W.T. 1988, c. J-1

- ↑ Judicature Act, R.S.N.S. 1989, c. 240

- ↑ Judicature Act, S.N.W.T. (Nu.) 1998, c. 34 s. 1

- ↑ Courts of Justice Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. C.43

- ↑ Judicature Act, R.S.P.E.I. 1988, c. J-2.1

- ↑ Courts of Justice Act, C.Q.L.R., c. T-16

- ↑ The Court of Appeal Act, S.S. 2000, c. C-42.1

- ↑ Court of Appeal Act, R.S.Y. 2002, c. 47

- ↑ Northwest Territories Act, S.C. 2014, c. 2, s. 2; Judicature Act, R.S.N.W.T. 1988, c. J-1

- ↑ Nunavut Act, S.C. 1993, c. 28; Judicature Act, S.N.W.T. (Nu.) 1998, c. 34 s. 1

- ↑ Yukon Act, S.C. 2002, c. 7; Supreme Court Act, R.S.Y. 2002, c. 211

- ↑ Federal Court Act, R.S.C. 1970 (2nd Supp.), c. 10

- ↑ Constitution Act, 1867, s. 96

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-12-06. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ Constitution Act, 1867, s. 133; Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s, 19(1)

- ↑ Official Languages Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.), Part III, Administration of Justice.

- ↑ Constitution Act, 1867, s. 133

- ↑ Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s. 19(2).

- ↑ Courts of Justice Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. C.43, ss. 125 and 126.

- ↑ Language Act / Loi linguistique, S.S. 1988, c. L-6.1, s. 11

- ↑ Language Act, R.S.A. 2000 cL-6, s. 4

- ↑ Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46, Part XVII.

- ↑ Official Languages Act, R.S.N.W.T. 1988, c. O-1, s. 9(2)

- ↑ Official Languages Act = ᑲᑎᑕᐅᓂᖓ ᐊᑕᐅᓯᕐᒧᑦ ᐃᓕᓴᕆᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐅᖃᐅᓰᑦ ᐱᖁᔭᖅ, S.Nu. 2008, c. 10, s. 8

- ↑ Styles of address

- ↑ "Criminal Code". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Senate. 17 February 2000. col. 1500–1510.

- Leishman, Rory, Against Judicial Activism : The Decline of Freedom and Democracy in Canada, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-7735-3054-1

Further reading

- Morton, Frederick Lee (2002), Law, politics, and the judicial process in Canada, Frederick Lee, ISBN 1-55238-046-7

- Riddell, Troy, Lori Hausegger, Matthew Hennigar (2008), Canadian courts : law, politics, and process, Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press Canada, ISBN 0-19-542373-9

External links

- a searchable database containing nearly all new and many older decisions emanating from all Canadian courts and most Canadian tribunals are available at the CanLII website and the decisions of individual courts are provided through that court's website (see partial list below)

- Canada's Court System from the Department of Justice Canada

- Supreme Court of Canada

- Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal

- Tax Court of Canada

- Courts of the Northwest Territories

- Courts of Yukon

- Nunavut Court of Justice

- Courts of British Columbia

- Courts of Alberta

- Courts of Manitoba

- Courts of Saskatchewan

- Courts of Ontario

- Courts of Quebec

- Courts of New Brunswick

- Courts of Newfoundland

- Courts of Nova Scotia

- Supreme Court of Prince Edward Island

- Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada

- Canadian Judicial Council

- Justice Canada - Judicial Appointments Press Releases (since 1999 for federal and subnational appointments)

- Justice Canada - Judicial Appointments Press Releases (since 1999 for federal and subnational appointments)