Cryptococcus

| Cryptococcus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Phylum: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Tremellomycetes |

| Order: | Tremellales |

| Family: | Tremellaceae |

| Genus: | Cryptococcus Vuill. |

| Type species | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Filobasidiella | |

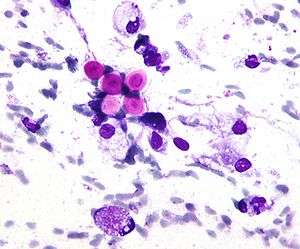

Cryptococcus (Greek for "hidden sphere") is a genus of fungus. These fungi grow in culture as yeasts. The sexual forms or teleomorphs of Cryptococcus species are filamentous fungi in the genus Filobasidiella. The name Cryptococcus is used when referring to the yeast states of the fungi.

General characteristics

The cells of these species are covered in a thin layer of glycoprotein capsular material that has a gelatin-like consistency and that, among other functions, serves to help extract nutrients from the soil. However, the C. neoformans capsule is different, in being richer in glucuronic acid and mannose, having O-acetyl groups,[1] and functioning as the major virulence factor in cryptococcal infection and disease.[2]

Infectious species

There are about 37 recognized species of Cryptococcus, but the taxonomy of the group is currently being re-evaluated with up-to-date methods. The majority of species live in the soil and are not harmful to humans. Very common species include Cryptococcus laurentii and Cryptococcus albidus. Of all species, Cryptococcus neoformans is the major human and animal pathogen. However, Cryptococcus laurentii and Cryptococcus albidus have been known to occasionally cause moderate-to-severe disease, to be specific meningitis, in human patients with compromised immunity (owing to HIV infection, cancer chemotherapy, metabolic immunosuppression, et cetera).[3][4]

C. neoformans

Cryptococcus neoformans is the most prominent medically important species. It is best known for causing a severe form of meningitis and meningo-encephalitis in people with HIV/AIDS. It may also infect organ transplant recipients and people receiving certain cancer treatments.[5] C. neoformans is found in the droppings of wild birds, often pigeons; when dust of the droppings is stirred up it can infect humans or pets that inhale the dust.[5] Infected humans and animals do not transmit their infection to others; they are not infectious.[5] When plated on Niger or birdseed agar, C. neoformans produces melanin, which causes the colonies to have a brown color, and it is believed that this melanin production may be an important virulence factor.[6]

C. gattii

Cryptococcus gattii (formerly Cryptococcus neoformans var gattii) is endemic to tropical parts of the continent of Africa and Australia. It is capable of causing disease (cryptococcosis) in non-immunocompromised people. It has been isolated from eucalyptus trees in Australia. Since 1999, there has been an outbreak of Cryptococcus gattii infections in eastern Vancouver Island,[7] an area not generally thought to be endemic for this organism. Cases have since been described in the Pacific Northwest, in both Canada and the United States.[8]

C. albidus

Cryptococcus albidus is a species that has been isolated from the air, dry moss in Portugal, grasshoppers in Portugal, and tubercular lungs.[9] The colonies on a macroscopic level are cream-color to pale pink, with the majority of colonies being smooth with a mucoid appearance. Some of the colonies have been found to be rough and wrinkled, but this is a rare occurrence.[10] This species is very similar to Cryptococcus neoformans, but can be differentiated because it is phenol oxidase-negative, and, when grown on Niger or birdseed agar, C. neoformans produces melanin, causing the cells to take on a brown color while the C. albidus cells stay cream-color.[6][11] On a microscopic level C. albidus has an ovoid shape, and when viewed with India ink it is apparent that a capsule is present. This species also reproduces through budding. The formation of pseudohyphae has not been seen. C. albidus is able to use glucose, citric acid, maltose, sucrose, trehalose, salicin, cellobiose, and inositol, as well as many other compounds, as sole carbon sources. This species is also able to use potassium nitrate as a nitrogen source. C. albidus produces urease, as is common for Cryptococcus species.[12] Cryptococcus albidus is very easily mistaken for other Cryptococcus species, as well as species from other genus of yeast, and as such should be allowed to grow for a minimum of seven days before attempting to identify this species.

While this species is most frequently found in water and plants and is also found on animal and human skin, it is not a frequent human pathogen. Cases of C. albidus infection have increased in humans during the past few years, and it has caused ocular and systemic disease in those with immunoincompetent systems, for example, patients with AIDS, leukemia, or lymphoma.[10][11] While systemic infections have been found with increasing regularity in humans, it is still relatively rare in animals. To date there have only been two cases of infection in horses, a case of systemic infection in a house cat, and in 2005 the first confirmed case of C. albidus systemic infection in a dog was confirmed. It is believed that C. albidus entered unencapsulated into a Doberman Pinscher named Daisy through her lungs, and infected the lung tissue. It is also believed that once the infection was embedded in Daisy’s lung tissue, the yeast became encapsulated, the presence of this important virulence factor thereby allowing C. albidus to spread through her system. While immunodeficiency seems to be required for a systemic infection of C. albidus to occur in humans, this does not appear to be the case in animals, though further studies will have to be done to confirm whether or not this is the case in animals. One thing that is confirmed is that a systemic infection in animals is typically seen when antibiotics are administered for extended periods of time. The only accepted treatment in humans and animals is the long-term administration of amphotericin B. The administration of amphotericin B in animals has been successful, but in humans the treatment usually has poor results.[6]

Cryptococcus albidus var. albidus is a variety of C. albidus that has been considered unique. It differs from Cryptococcus neoformans because of its ability to assimilate lactose, but not galactose. This species is also considered unique because its strains have a maximum temperature range from between 25 °C and 37 °C. This is important because it violates van Uden’s rule, which states that the yeast strains of a particular species cannot have their maximum growth temperature vary by more than 5 °C.[13] However, there is some debate as to whether or not this maximum temperature range for the strains of C. albidus is accurate, because other research has shown that C. albidus var. albidus strains cannot grow at 37 °C.[11] Another variety, Cryptococcus albidus var. diffluens is different from Cryptococcus neoformans in that it can assimilate melibiose but not galactose.[6]

C. uniguttulatus

Cryptococcus uniguttulatus (Filobasidium uniguttulatus is a teleomorph) was the first non-neoformans Cryptococcus to infect a human. It was isolated from ventricular fluid from a patient having had a neurosurgical procedure. This species was found to be very sensitive to amphotericin B at the minimum inhibitory dose. This species was first isolated from a human nail.

Non-infectious species

- Cryptococcus adeliensis

- Cryptococcus aerius

- Cryptococcus albidosimilis

- Cryptococcus antarcticus

- Cryptococcus aquaticus

- Cryptococcus ater

- Cryptococcus bhutanensis

- Cryptococcus consortionis

- Cryptococcus curvatus

- Cryptococcus phenolicus

- Cryptococcus skinneri

- Cryptococcus terreus

- Cryptococcus vishniacci

References

- ↑ Ross A, Taylor IE (1981) Extracellular glycoprotein from virulent and avirulent Cryptococcus species. Infection and Immunity. 31(3):911–8

- ↑ Casadevall A and Perfect JR (1998) Cryptococcus neoformans. American Society for Microbiolgy, ASM Press, Washington DC, 1st edition.

- ↑ Cheng MF, Chiou CC, Liu YC, Wang HZ, Hsieh KS (2001) Cryptococcus laurentii fungemia in a premature neonate. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 39(4):1608–11. A good review of C. laurentii cases till year 2000.

- ↑ Results from a PubMed Search on terms: "Cryptococcus albidus Infection" – list of references for C. albidus clinical infections.

- 1 2 3 "What is Cryptococcus infection (cryptococcosis)?". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. April 28, 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Labrecque O., Sylvestre D. and Messier S. (2005) Systemic Cryptococcus albidus infection in a Doberman Pinscher. J Vet Diagn Invest 17:598-600

- ↑ Lindberg J, Hagen F, Laursen A, et al. (2007). "Cryptococcus gattii Risk for Tourists Visiting Vancouver Island, Canada". Emerg Infect Dis. 13 (1): 178–79. doi:10.3201/eid1301.060945. PMC 2725802

. PMID 17370544.

. PMID 17370544. - ↑ MacDougall L, Kidd SE, Galanis E, et al. (2007). "Spread of Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia, Canada, and Detection in the Pacific Northwest, USA". Emerg Infect Dis. 13 (1): 42–50. doi:10.3201/eid1301.060827. PMC 2725832

. PMID 17370514.

. PMID 17370514. - ↑ Fonseca A., Scorzeti G., and Fell J. (2000) Diversity in the yeast Cryptococcus albidus and related species as revealed by ribosomal DNA sequence analysis. Can. J. Microbiol. 46:7-27

- 1 2 http://www.doctorfungus.org/thefungi/Cryptococcus_albidus.php Results from a search on Doctor Fungus

- 1 2 3 (2006) 0609-1 Cryptococcus albidus. Cmpt Mycol Plus

- ↑ Cryptococcus albidus. Mycology Online. The University of Adelaide. http://www.mycology.adelaide.edu.au/Fungal_Descriptions/Yeasts/Cryptococcus/C_albidus.html

- ↑ Vishniac H. S., Kurtzman C. P. (1992) Cryptococcus anarcticus sp. nov. and Cryptococcus albidosimilis sp. nov., Basidioblasomycetes from Antarctic Soils. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42(4) 547-553

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Cryptococcus (Tremellaceae) |