Cumberland Basin (Bristol)

| Cumberland Basin | |

|---|---|

|

The basin looking eastwards | |

Cumberland Basin Location within Bristol | |

| Coordinates: 51°26′53″N 2°37′10″W / 51.44806°N 2.61944°WCoordinates: 51°26′53″N 2°37′10″W / 51.44806°N 2.61944°W | |

| Country | England |

| City | Bristol |

| District | Hotwells |

| Established | 1804-9 |

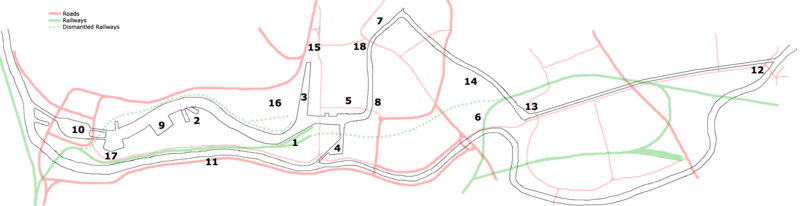

The Cumberland Basin is the main entrance to the docks of the city of Bristol, England. It separates the areas of Hotwells from the tip of Spike Island.

History

The River Avon never flowed through the Cumberland Basin. Before the 19th century improvements and the construction of the non-tidal Floating Harbour, the Avon flowed through the tidal harbour and out through the future location of the Underfall Yard. When the basin and Floating Harbour were constructed the river was diverted through the New Cut, bypassing the harbour entirely.

Following competition from other ports, in 1802 William Jessop proposed installing a dam and lock at Hotwells to create the harbour. The £530,000 scheme was approved by Parliament, and construction began in May 1804. The scheme included the construction of the Cumberland Basin, a large wide stretch of the harbour in Hotwells where the Quay walls and bollards have listed building status.[1][2]

The new scheme required a way to equalise the levels inside and outside the Dock for the passage of vessels to and from the Avon, and bridges to cross the water. Jessop built Cumberland Basin with two entrance locks from the tidal Avon, of width 45 ft (13.7 m) and 35 ft (10.7 m), and a 45 feet (13.7 m) wide junction lock between the Basin and what became known as the Floating Harbour. This arrangement provided flexibility of operation with the Basin being used as a lock when there were large numbers of arrivals and sailings. The harbour was officially opened on 1 May 1809.[3] The first alteration was the construction of the south junction lock which was completed in 1849 and had a single-leaf wrought-iron gate. It is no longer used and has been sealed by a concrete wall.[4]

In 1831 a terrace of eight houses were built for the Bristol Docks Company.[5][6] In 1870 a hydraulic pump house was built by Thomas Howard to power the bridges and machinery. It has since been converted into the Pump House pub,[7] with hydraulic power being provided from the Hydraulic engine house at the Underfall Yard.

Swing bridges

When Brunel rebuilt the entrance locks of the Cumberland Basin in Bristol Harbour, between 1848–1849, he also constructed a number of swinging bridges – Brunel's first moving bridges.[8] These were of centre-pivot construction, but were highly asymmetrical, the outboard side being nearly three times longer than the landward, balanced by large cast iron counterweights.[8]

As the bridges were for light roadways and did not have to carry the weight of a railway or train, their girders were of a lightweight construction, known as Balloon flange girders that simplified manufacture. A full balloon upper flange was used, similar in shape to the South Wales Railway bridges, but the flange sat above the main web of the girder and the web did not span the flange and reach to the top. This simplified construction as it avoided the T-joint, the necessary L-strips and thus several rows of riveting.[8] The lower flange was of an entirely novel form, being triangular in section, although with concave sides. Again, the main web did not span the flange. All three joints were now simple lap joints with single-row riveting.[8]

One of the bridges was moved from the south entrance lock to the north entrance dock in 1873. It was originally hand cranked and later adapted to use hydraulic power.[9] It became redundant in the 1960s when it was replaced by the large Plimsoll Swing Bridge and was left on the side of the dock partially beneath the new bridge.[10] It is now known as "Brunel's other bridge" to differentiate it from the nearby Clifton Suspension Bridge.[11] The old Junction Lock swing bridge is powered by water pressure from the Underfall Yard hydraulic engine house at 750 psi (52 bar). The new Plimsoll Bridge, completed in 1965, has a more modern electro-hydraulic system using oil at a pressure of 4,480 psi (309 bar).[3]

Like a number of early Brunel bridges, Brunel's involvement with them was largely forgotten and only recorded in obscure works.[12] At one point they were under serious threat of demolition until their historical significance was re-recognised. It is listed on the Heritage at Risk register.[13] A £1 million appeal was launched in 2014 to restore the bridge,[11][14] and English Heritage has offered a grant towards its restoration.[13]

- Prince's Wharf, including M Shed, Pyronaut and Mayflower adjoining Prince Street Bridge

- Dry docks: SS Great Britain, the Matthew

- St Augustine's Reach, Pero's Bridge

- Bathurst Basin

- Queen Square

- Bristol Temple Meads railway station

- Castle Park

- Redcliffe Quay and Redcliffe Caves

- Baltic Wharf marina

- Cumberland Basin & Brunel Locks

- The New Cut

- Netham Lock, entrance to the Feeder Canal

- Totterdown Basin

- Temple Quay

- The Centre

- Canons Marsh, including Millennium Square and At-Bristol

- Underfall Yard

- Bristol Bridge

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cumberland Basin. |

- ↑ "Quay walls and bollards". Images of England. Retrieved 18 August 2006.

- ↑ "Quay walls and bollards around Cumberland Basin". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- 1 2 "The creation of Bristol City docks". Farvis. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "Brunel's South Entrance Lock". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "Nos.1-5 (Consecutive) Old Dock Cottages". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "Nos.6, 7 AND 8 Old Dock Cottages". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "The Pump House Public House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Isambard Brunel Junior (2006) [1870]. The Life of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Civil Engineer. STEAM / Nonsuch Publishing. pp. 146–149. ISBN 978-1845880316.

- ↑ Fells, Maurice (2014). The A-Z of Curious Bristol. History Press. p. 17-18. ISBN 978-0750956055.

- ↑ "Cumberland Basin Bridges (Bristol)". Grace's Guide. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Brunel's other bridge in Bristol may be repaired as £1m appeal launched". BBC News Online. 10 October 2014.

- ↑ Buchanan, Angus; Williams, Michael (1982). Brunel's Bristol. Redcliffe Press. p. 31. ISBN 0905459393.

- 1 2 "Swing Bridge over North Entrance Lock, Cumberland Basin, Bristol - Bristol, City of (UA)". Heritage at Risk. Historic England. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "Brunel's Other Bridge". Brunel's Other Bridge Committee. Retrieved 22 March 2015.