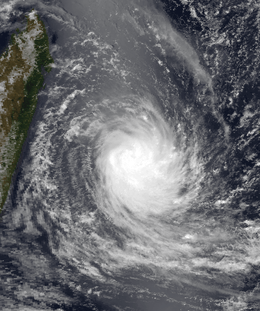

Cyclone Firinga

| Tropical cyclone (SWIO scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 2 (Saffir–Simpson scale) | |

Cyclone Firinga near peak intensity | |

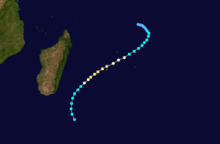

| Formed | January 24, 1989 |

| Dissipated | February 7, 1989 |

| Highest winds |

10-minute sustained: 135 km/h (85 mph) 1-minute sustained: 165 km/h (105 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 954 hPa (mbar); 28.17 inHg |

| Fatalities | 11 total |

| Damage | $217 million (1989 USD) |

| Areas affected | Mauritius, Réunion |

| Part of the 1988–89 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season | |

Cyclone Firinga produced record-breaking rainfall on the French overseas department of Réunion. It was the sixth named storm of the season, having developed on January 24, 1989 in the south-west Indian Ocean. Given the name Firinga, it moved generally southwestward for much of its duration. While the cyclone was approaching Mauritius late on January 28, it attained peak winds of 135 km/h (85 mph). Firinga passed 50 km (31 mi) west of the island, producing 190 km/h (120 mph) wind gusts that destroyed 844 homes. Heavy crop damage occurred on the island, and damage nationwide was estimated at $60 million (1989 USD). One person was killed in Mauritius.

After passing Mauritius, Firinga struck Réunion early on January 29 with wind gusts as strong as 216 km/h (134 mph). The storm dropped torrential rainfall in the southern portion of the island, including 24‑hour totals of 1,309 mm (51.5 in) at Pas de Bellecombe and 1,199 mm (47.2 in) at Casabois, both of which set records for the locations. The rains caused widespread river flooding and resulted in 32 mudslides. Firinga isolated several towns due to flooding and left power and water outages. A total of 2,746 houses were damaged or destroyed, leaving 6,200 people homeless. Damage was estimated at around ₣1 billion (1989 francs, $157 million 1989 USD), and there were 10 deaths on the island. Firinga later dissipated on February 7 after having weakened and executed a loop to the southeast.

Meteorological history

On January 24, both the Météo France office in Réunion (MFR)[nb 1] and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)[nb 2] began tracking a tropical disturbance in the south-west Indian Ocean, about halfway between the east coast of Madagascar and Diego Garcia;[3] the latter agency designated it as Tropical Cyclone 08S.[4] After initially moving to the southeast, the system later turned to the southwest and gradually intensified. Given the name Firinga, the system intensified into a moderate tropical storm on January 26. Two days later, the JTWC upgraded the storm to the equivalent of a minimal hurricane while Firinga was approaching Mauritius.[3] Late on January 28, the cyclone passed about 50 km (31 mi) northwest of the island.[5] Shortly thereafter, MFR upgraded Firinga to tropical cyclone status, estimating 10 minute maximum sustained winds[nb 3] of 135 km/h (85 mph). At the same time, the JTWC estimated 1 minute winds of 165 mph (105 mph).[3]

Shortly after 0600 UTC on January 29, Firinga made landfall on Réunion while at peak intensity. It quickly crossed the island and began weakening; MFR downgraded the storm below cyclone status at 1200 UTC that day. The JTWC followed suit on January 30, and the next day Firinga began turning to the south. On February 1, the JTWC discontinued advisories, although MFR continued tracking the storm. After turning to the east and executing a loop to the southwest, Firinga was last observed on February 7.[3]

Preparations and impact

On January 28 while Firinga was approaching Réunion, officials on the island issued a level 1 tropical cyclone alert on the Organisation de la Réponse de SÉcurité Civile (ORSEC) plan. By the next day, this was raised to a level 3 when landfall was imminent.[7] The government of Mauritius also warned the citizens of the approach of the storm.[5]

Before affecting Réunion, the cyclone passed near Mauritius with wind gusts up to 190 km/h (120 mph). Much of the island lost power, water, and telephone access; the water system was disrupted when cleaning systems were damaged. The storm destroyed over 70% of the island's crops, including wrecking 5,000 metric tons (5,500 tons) of sugar. In addition, Firinga destroyed 844 houses in Mauritius. Throughout the island, the cyclone killed one person, injured 507, and left about $60 million (1989 USD) in damage.[5]

While in the vicinity of Réunion, Firinga produced a minimum pressure of 962 mbar (28.4 inHg) at Pointe des Galets. Sustained winds throughout the island reached at least 130 km/h (81 mph) with gusts of over 180 km/h (110 mph). The peak gust was 216 km/h (134 mph) at Saint-Pierre, and the capital Saint-Denis reported gusts of 178 km/h (111 mph).[7] In addition to the winds, Firinga dropped record heavy rainfall on Réunion, including a report of 170 mm (6.7 in) that broke the record for an hour total at Plaine des Cafres, and 600 mm (24 in) that broke the record for a six-hour total at Saint-Joseph. Totals over 24 hours included 1,309 mm (51.5 in) at Pas de Bellecombe, and 1,199 mm (47.2 in) at Casabois, both of which set records for the locations.[8] Rainfall was lighter along the east and west coasts of the island, but highest in the central plains and in the south, where totals were 1 in 50 year events. Due to the strong winds possibly disrupting instruments, rainfall totals may have been higher than what were recorded. Firinga also produced high waves along the island, reaching 17 m (56 ft) along the eastern coast. The high rainfall resulted in the Rivière Langevin to overflow its banks, causing significant flooding in Saint-Denis. The highest flow rate was 1,100 m3/s/s (38,846 ft3/s/s) along the Rivière des Remparts. Several rivers changed their courses due to the high volume of water, and high sediment carried by rivers disrupted lagoon systems. The high rainfall caused 32 landslides throughout Réunion, most of which were small; however, one in La Plaine-des-Palmistes damaged a road.[7]

The floods damaged roads, buildings, and farmlands along their path. At Salazie, the storm destroyed a bridge, which restricted traffic to Cilaos. Coastal roads were damaged, with several washed out near Saint-Pierre; one road had a cut 60 m (200 ft) in length. The Rivière Langevin destroyed a bridge, and flooding near Bras-Piton wrecked 400 m (1,300 ft) of roads. Road damage alone was estimated at ₣137 million (1989 francs, $26 million USD).[7][nb 4] At least four towns were isolated due to storm damage.[7] High winds left 60% of the island without power,[10] mostly in the southern portion including Saint-Joseph and Cilaos. The latter town also lost telephone service.[7] Widespread areas lost water access due to flooding washing out two main water lines, affecting about 60,000 people.[8] High winds left heavy crop damage, mostly to banana trees and vegetables. In L'Étang-Salé, all of the fruit trees were knocked down, and in Entre-Deux, 5,000 hens and several livestock died. In Sainte-Marie, a landslide wrecked about half of the sugar crop.[7] Island-wide, Firinga destroyed 970 houses and damaged 1,776 others,[7] leaving 6,200 people homeless.[11] Most of the damaged houses were in Saint-Pierre,[7] and the heaviest damage generally occurred in towns along floodplains.[8] During the storm, 10 people died throughout Réunion,[11] four of whom in the town of Le Tampon.[7] There were also 62 injuries.[11] Overall damage was initially estimated at around ₣1 billion (1989 francs, $157 million 1989 USD).[7][nb 4] On the island, Firinga was the third significant cyclone of the 1980s, after Cyclone Hyacinthe in 1980 and Cyclone Clotilda in 1987.[8]

Aftermath

On Mauritius, power and water were gradually restored following the storm, and people without power used generators. The United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs provided $10,000 (1989 USD) to the country to purchase water tanks and saws.[5]

After the storm, officials in Réunion declared a disaster area for the island. The government started an emergency relief fund to provide assistance to the affected families. The European Economic Community donated ₣1.42 million francs ($222,000 1989 USD)[nb 4] due to the storm. Residents on the island assisted each other by providing lodging and donating clothing.[8] France sent 15,000 ration kits, 1,500 beds and blankets, and 20 cisterns to the island in the aftermath of Firinga. In addition, 400 troops and 50 vehicles were dispatched from an insular military base in order to assist the affected populations.[12] Within two days, crews in Réunion restored water access to about 20,000 people. Conditions returned to normal in northern Réunion within about a day. In the southern portion, however, it took up to four weeks for life to return to normal.[7] The significant amount of flooding damaged the coral reef system due to excessive runoff. Due to dead animals being washed into the ocean, diving at the reefs was banned for several weeks.[13] The waves had damaged the coral reef system to such extent that there was no regrowth after seven years.[7]

Notes

- ↑ The Météo-France office in Réunion is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the basin.[1]

- ↑ The Joint Typhoon Warning Center is a joint United States Navy – United States Air Force task force that issues tropical cyclone warnings for the region.[2]

- ↑ Wind estimates from Météo-France and most other basins throughout the world are sustained over 10 minutes, while estimates from the United States-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center are sustained over 1 minute. 10 minute winds are about 1.14 times the amount of 1 minute winds.[6]

- 1 2 3 Original currency in 1989 Francs, converted to United States dollars via FXTOP.com.[9]

References

- ↑ Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Centers (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. 2011-09-11. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑ "Joint Typhoon Warning Center Mission Statement". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 2011. Archived from the original on 2007-07-26. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- 1 2 3 4 Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1989 Firinga (1989024S11064). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2013-07-30.

- ↑ Best Track Data for Tropical Cyclone 08S (Firinga) (TXT) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- 1 2 3 4 United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (February 1989). Mauritius - Cyclone Firinga Feb 1989 UNDRO Situation Reports 1-3 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- ↑ Christopher W Landsea; Hurricane Research Division (2006-04-21). "Subject: D4) What does "maximum sustained wind" mean? How does it relate to gusts in tropical cyclones?". Frequently Asked Questions:. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Synthése e Des Événements: Firinga, Cyclone Tropical Modéré (29 Janvier 1989)" (PDF) (in French). Les Risques Naturales á la Réunion. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 C. Decelle; L. Denervaud; L. Stieltjes (July 1989). Inventaire des mouvements de terrains et inondations liés au cyclone Fininga (29 janvier 1989) ayant affecté des équipements ou aménagements collectifs et individuels à la Réunion (PDF) (Report) (in French). Ministere de l'Industrie et de L'Amanagement du Territoire. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- ↑ "Currency Converter from Francs to United States dollars". FXTOP.com. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ "Indian Ocean Storm Hurts 30 Islanders". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. 1989-01-30. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (August 1993). Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide 1900-present (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ↑ "France Sends Emergency Aid to Cyclone Victims on Reunion". Paris, France. Associated Press. 1989-01-30. International News. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ↑ Yves Letourneur; Mireille Harmelin-Vivien; René Galzin (June 1993). "Impact of hurricane Firinga on fish community structure on fringing reefs of Reunion Island, S.W. Indian Ocean". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 37 (2): 109–110. doi:10.1007/bf00000586. Retrieved 2013-08-06.