Cystinosis

| Cystinosis | |

|---|---|

| |

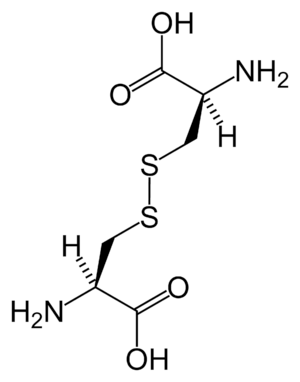

| Chemical structure of cystine formed from L-cysteine (under biological conditions) | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | endocrinology |

| ICD-10 | E72.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 270.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 3382 |

| eMedicine | ped/538 |

| MeSH | D003554 |

Cystinosis is a lysosomal storage disease characterized by the abnormal accumulation of the amino acid cystine.[1] It is a genetic disorder that typically follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Cystinosis is the most common cause of Fanconi syndrome in the pediatric age group. Fanconi syndrome occurs when the function of cells in renal tubules are impaired, leading to abnormal amounts of carbohydrates and amino acids in the urine, excessive urination, and low blood levels of potassium and phosphates.

Cystinosis was the first documented genetic disease belonging to the group of lysosomal-transport-defect disorders.[2] It is a rare autosomal recessive disorder resulting from accumulation of free cystine in lysosomes, eventually leading to intracellular crystal formation throughout the body. Cystinosis is caused by mutations in the CTNS gene that codes for cystinosin, the lysosomal membrane-specific transporter for cystine. Intracellular metabolism of cystine, as it happens with all amino acids, requires its transport across the cell membrane. After degradation of endocytosed protein to cystine within lysosomes, it is normally transported to the cytosol. But if there is a defect in the carrier protein, cystine is accumulated in lysosomes. As cystine is highly insoluble, when its concentration in tissue lysosomes increase, its solubility is immediately exceeded and crystalline precipitates are formed in almost all organs and tissues.[3]

However, the progression of the disease is not related to the presence of crystals in target tissues. Although tissue damage might depend on cystine accumulation, the mechanisms of tissue damage are not fully understood. Increased intracellular cystine profoundly disturbs cellular oxidative metabolism and glutathione status,[4] leading to altered mitochondrial energy metabolism, autophagy, and apoptosis.[5]

Cystinosis is usually treated with cysteamine, which is prescribed to decrease intralysosomal cystine accumulation.[6] However, the recent discovery of new pathogenic mechanisms and the development of an animal model of the disease may open possibilities for the development of new treatment modalities to improve long-term prognosis.[2]

Diagnosis

Cystinosis is a rare genetic disorder[7] that causes an accumulation of the amino acid cystine within cells, forming crystals that can build up and damage the cells. These crystals negatively affect many systems in the body, especially the kidneys and eyes.[1]

The accumulation is caused by abnormal transport of cystine from lysosomes, resulting in a massive intra-lysosomal cystine accumulation in tissues. Via an as yet unknown mechanism, lysosomal cystine appears to amplify and alter apoptosis in such a way that cells die inappropriately, leading to loss of renal epithelial cells. This results in renal Fanconi syndrome,[8] and similar loss in other tissues can account for the short stature, retinopathy, and other features of the disease.

Definitive diagnosis and treatment monitoring are most often performed through measurement of white blood cell cystine level using tandem mass spectrometry.

Symptoms

There (are) three distinct types of cystinosis each with slightly different symptoms: nephropathic cystinosis, intermediate cystinosis, and non-nephropathic or ocular cystinosis. Infants affected by nephropathic cystinosis initially exhibit poor growth and particular kidney problems (sometimes called renal Fanconi syndrome). The kidney problems lead to the loss of important minerals, salts, fluids, and other nutrients. The loss of nutrients not only impairs growth, but may result in soft, bowed bones (hypophosphatemic rickets), especially in the legs. The nutrient imbalances in the body lead to increased urination, thirst, dehydration, and abnormally acidic blood (acidosis).

By about age two, cystine crystals may also be present in the cornea. The buildup of these crystals in the eye causes an increased sensitivity to light (photophobia). Without treatment, children with cystinosis are likely to experience complete kidney failure by about age ten. Other signs and symptoms that may occur in untreated patients include muscle deterioration, blindness, inability to swallow, impaired sweating, decreased hair and skin pigmentation, diabetes, and thyroid and nervous system problems.

The signs and symptoms of intermediate cystinosis are the same as nephropathic cystinosis, but they occur at a later age. Intermediate cystinosis typically begins to affect individuals around age twelve to fifteen. Malfunctioning kidneys and corneal crystals are the main initial features of this disorder. If intermediate cystinosis is left untreated, complete kidney failure will occur, but usually not until the late teens to mid twenties.

People with non-nephropathic or ocular cystinosis do not usually experience growth impairment or kidney malfunction. The only symptom is photophobia due to cystine crystals in the cornea.

Research into cystinosis is currently being conducted at the University of California, San Diego, The Scripps Research Institute, University of California, Irvine, Baylor College of Medicine, University of Michigan, Tulane University School of Medicine, and the National Institutes of de Duve Institute, Belgium, NIH in Bethesda, Maryland, as well as at Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen, Scotland, University of Sunderland, UK, University College Dublin, Ireland, University College Cork, Ireland and the Necker Hospital in Paris.

Crystal morphology and identification

Cystine crystals are hexagonal in shape and are colorless. They are not found often in alkaline urine due to their high solubility. The colorless crystals can be difficult to distinguish from uric acid crystals which are also hexagonal. Under polarized examination, the crystals are birefringent with a polarization color interference.[9]

Genetics

Cystinosis occurs due to a mutation in the gene CTNS, located on chromosome 17, which codes for cystinosin, the lysosomal cystine transporter. Symptoms are first seen at about 3 to 18 months of age with profound polyuria (excessive urination), followed by poor growth, photophobia, and ultimately kidney failure by age 6 years in the nephropathic form.

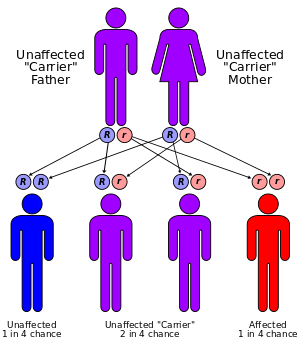

All forms of cystinosis (nephropathic, juvenile and ocular) are autosomal recessive, which means that the trait is located on an autosomal gene, and an individual who inherits two copies of the gene – one from both parents – will have the disorder. There is a 25% risk of having a child with the disorder, when both parents are carriers of an autosomal recessive trait.

Cystinosis affects approximately 1 in 100,000 to 200,000 newborns.[10] and there are only around 2,000 known individuals with cystinosis in the world. The incidence is higher in the province of Brittany, France, where the disorder affects 1 in 26,000 individuals.[11]

Treatment

Cystinosis is normally treated with a drug called cysteamine (brand name Cystagon).[12] The administration of cysteamine can reduce the intracellular cystine content. Cysteamine concentrates inside the lysosomes and reacts with cystine to form both cysteine and a cysteine-cysteamine complex, which are able to leave the lysosomes. When administered regularly, cysteamine decreases the amount of cystine stored in lysosomes and correlates with conservation of renal function and improved growth.[12] Cysteamine eyedrops remove the cystine crystals in the cornea that can cause photophobia if left unchecked. Patients with cystinosis are also often given sodium citrate to treat the blood acidosis, as well as potassium and phosphorus supplements. If the kidneys become significantly impaired or fail, then treatment must be begun to ensure continued survival, up to and including renal transplantation.

Cystaran, (cysteamine ophthalmic solution) 0.44%, was approved by the FDA in 2013 for the treatment of corneal cystine crystal accumulation in patients with cystinosis. Procysbi, an extended-release formulation of cysteamine, was approved by the FDA in 2013.[13]

Types

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 219800 – Infantile nephropathic

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 219900 – Adolescent nephropathic

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 219750 – Adult nonnephropathic

Cystinotic

The related adjective "cystinotic" indicates "relating to, or afflicted with, cystinosis".

See also

References

- 1 2 A. Gahl, William; Jess G. Thoene; Jerry A. Schneider (2002). "Cystinosis". N Engl J Med. 347 (2): 111–121. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020552. PMID 12110740.

- 1 2 Nesterova G, Gahl WA. Cystinosis: the evolution of a treatable disease. Pediatr Nephrol 2012;28:51–9.

- ↑ Gahl WA, Thoene JG,Schneider JA. Cystinosis. N Engl J Med 2002;347:111-121.

- ↑ Kumar A, Bachhawat AK. A futile cycle, formed between two ATP-dependant γ-glutamyl cycle enzymes, γ-glutamyl cysteine synthetase and 5-oxoprolinase: the cause of cellular ATP depletion in nephrotic cystinosis?; J Biosci 2010;35:21–25.

- ↑ Park MA,Thoene JG. Potential role of apoptosis in development of the cystinotic phenotype. Pediatr Nephrol 2005;20:441–446.

- ↑ Besouw M, Masereeuw R, Van den Heuvel L et al. Cysteamine: an old drug with new potential. Drug Discov Today 2013.

- ↑ Cystinosis

- ↑ Howard G. WORTHEN; Robert A. GOOD (1958). "The de Toni-Fanconi Syndrome with Cystinosis". AMA J Dis Child. 95 (6): 653–688. PMID 13532161.

- ↑ Spencer, Daniel. "Cystine". CRYSTALS. Urinalysis (Texas Collaborative for Teaching Excellence). Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ "Cystinosis on Genetic home reference".

- ↑ Kalatzis, V; Cherqui S; Jean G; Cordier B; Cochat P; Broyer M; Antignac C (October 2001). "Characterization of a putative founder mutation that accounts for the high incidence of cystinosis in Brittany". J Am Soc Nephrol. 12 (10): 2170–2174. PMID 11562417. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- 1 2 Gahl, William A.; George F. Reed; Jess G. Thoene; Joseph D. Schulman; William B. Rizzo; Adam J. Jonas; Daniel W. Denman; James J. Schlesselman; Brian J. Corden; Jerry A. Schneider (1987). "Cysteamine Therapy for Children with Nephropathic Cystinosis". N Engl J Med. 316 (16): 971–977. doi:10.1056/NEJM198704163161602. PMID 3550461.

- ↑ "FDA approves Procysbi for rare genetic condition" (Press release). 2013-04-30. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

External links

- Cystinosis at NLM Genetics Home Reference

- Cystinosis Foundation, Inc – A 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, educating and supporting patients, families, and medical professionals since 1983.

- Cystinosis Research Network – a non-profit organization advocating research, providing family assistance, and educating the public about cystinosis.

- Cure Cystinosis International Registry – the only international patient registry. A hub of information on cystinosis and its complications. Registrants contribute to research and are informed about available clinical trials and studies

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Cystinosis

- Cystinosis Research Foundation a non- profit foundation that focuses on research that will lead to better treatments and a cure. Leading fund provider of research grants in the world. Sponsors annual family conference and a biennial international research symposium.

- Know Cystinosis – a resource for the latest disease information and how to diagnose, manage, and live with Cystinosis

- BC Health Guide

- Cystinosis Foundation UK – a UK Charity Supporting Families & Research

- Cystinosis Foundation Ireland – an all-volunteer Irish Charity investing in Research and supporting those living with Cystinosis in Ireland

- Hide and Seek Foundation For Lysosomal Disease Research