Danish India

| Danish India | ||||||||||

| Dansk Østindien | ||||||||||

| Danish East India Company (1620–1777) Dano-Norwegian colonies (1777–1814) Danish colonies (1814–1869) | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

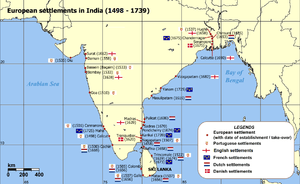

Danish and other European settlements in India | ||||||||||

| Capital | Fort Dansborg | |||||||||

| Languages | Danish, Tamil, Hindustani, Bengali | |||||||||

| Political structure | Colonies | |||||||||

| King of Denmark (and Norway until 1814) | ||||||||||

| • | 1588–1648 | Christian IV | ||||||||

| • | 1863–1906 | Christian IX | ||||||||

| Governor | ||||||||||

| • | 1620–1621 | Ove Gjedde | ||||||||

| • | 1673–1682 | Sivert Cortsen Adeler | ||||||||

| • | 1759–1760 | Christian Frederik Høyer | ||||||||

| • | 1788–1806 | Peter Anker | ||||||||

| • | 1825–1829 | Hans de Brinck-Seidelin | ||||||||

| • | 1841–1845 | Peder Hansen | ||||||||

| Historical era | Colonial period | |||||||||

| • | Established | 1620 | ||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 1869 | ||||||||

| Currency | Danish Indian Rupee | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||

Danish India was the name given to the colonies of Denmark (Denmark–Norway before 1813) in India, forming part of the Danish colonial empire. Denmark-Norway held colonial possessions in India for more than 200 years, including the town of Tharangambadi in present-day Tamil Nadu state, Serampore in present-day West Bengal, and the Nicobar Islands, currently part of India's union territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The Danish presence in India was of little significance to the major European powers as they presented neither a military nor a mercantile threat.[1] Dano-Norwegian ventures in India, as elsewhere, were typically undercapitalised and never able to dominate or monopolise trade routes in the same way that the companies of Portugal, the Netherlands and Britain could.[2][3] Against all odds however they managed to cling to their colonial holdings, and at times, to carve out a valuable niche in international trade by taking advantage of wars between larger countries and offering foreign trade under a neutral flag.[4][5] For this reason their presence was tolerated until 1845, when their alliance with a defeated France led to the colony being ceded to the British East Indian company.

History

|

Imperial entities of India | |

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 |

|---|---|

| Danish India | 1620–1869 |

| French India | 1769–1954 |

| Casa da Índia | 1434–1833 |

| Portuguese East India Company | 1628–1633 |

| East India Company | 1612–1757 |

| Company rule in India | 1757–1858 |

| British Raj | 1858–1947 |

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1948 |

| Princely states | 1721–1949 |

| Partition of India |

1947 |

|

| |

The success of Dutch and English traders in the 17th century spice trade was a source of envy among Danish and Norwegian merchants.[6] On March 17, 1616, Christian IV the King of Denmark-Norway, issued a charter creating a Danish East India Company with a monopoly on trade between Denmark-Norway and Asia for 12 years. It would take an additional two years before sufficient capital had been raised to finance the expedition, perhaps due to lack of confidence on the part of Danish investors. It took the arrival of the Dutch merchant and colonial administrator, Marchelis de Boshouwer, in 1618 to provide the impetus for the first voyage. Marcelis arrived as an envoy (or at least claimed to do so) for the emperor of Ceylon, Cenerat Adassin, seeking military assistance against the Portuguese and promising a monopoly on all trade with the island. His appeal had been rejected by his countrymen, but it convinced the Danish King.[7]

First expedition (1618–1620)

The first expedition set sail in 1618 under Admiral Ove Gjedde, taking two years to reach Ceylon and losing more than half their crew on the way. Upon arriving in May 1620, they found the emperor no longer desiring any foreign assistance having made a peace agreement with the Portuguese three years earlier. Nor, to the dismay of the Admiral, was the Emperor the sole, or even the "most distinguished king in this land".[8] Failing to get the Dano-Norwegian-Ceylonese trade contract confirmed, the Dano-Norwegians briefly occupied the Koneswaram temple before receiving word from their Trade Director, Robert Crappe.

Crappe had sailed on the scouting freighter the Øresund one month prior to the main fleet. The Øresund had encountered Portuguese vessels off the Karaikkal coast and was sunk, with most of the crew killed, or taken prisoner. The heads of two crew members were placed on spikes on the beach as a warning to the Dano-Norwegians. Crappe and 13 of the crew however had escaped the wreck, making it to shore where they were captured by Indians and taken to the Nayak of Tanjore (now Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu). The Nayak turned out to be interested in trading opportunities and Crappe managed to negotiate a treaty granting them the village of Tranquebar (or Tharangamabadi)[9] and the right to construct a "stone house" (Fort Dansborg) and levy taxes.[10] This was signed on 20 November 1620.

Early years (1621–1639)

The early years of the colony were arduous, with poor administration and investment, coupled with the loss of almost two-thirds of all the trading vessels dispatched from Denmark.[11] The ships that did return made a profit on their cargo, but total returns fell well short of the costs of the entire venture.[12] Moreover, the geographical location of the colony was vulnerable to high tidal waves which repeatedly destroyed what people built—roads, houses, administrative buildings, markets, etc.[13] Although the intention had been to create an alternative to the English and Dutch traders, the dire financial state of the company and the redirection of national resources towards the Thirty Years' War led the colony to abandon efforts to trade directly for themselves, and instead to become neutral third party carriers for goods in the Bay of Bengal.

By 1625 a factory had been established at Masulipatnam, the most important emporium in the region, and lesser trading offices were established at Pipli and Balasore. Despite this, by 1627 the colony was in such a poor financial state that it had just three ships left in its possession and was unable to pay the agreed-upon tribute to the Nayak, increasing local tensions. The Danish presence was also unwanted by English and Dutch traders who believed them to be operating under the protection of their navies without bearing any of the costs. Despite this, they could not crush Danish trade, due to diplomatic implications related to their respective nations' involvement in the European wars.[14]

- 1640 – Danes attempt to sell Fort Danesborg to the Dutch for a second time.

- 1642 – Danish colony declares war on Mogul Empire and commences raiding ships in the Bay of Bengal. Within a few months they had captured one of the Mogul emperor's vessels, incorporated it into their fleet (renamed the Bengali Prize) and sold the goods in Tranquebar for a substantial profit.

- 1643 – Willem Leyel, designated the new leader of the colony by the company directors in Copenhagen arrives aboard the Christianshavn. Holland and Sweden declare war on Denmark.

- 1645 – Danish factory holdings fall increasingly under Dutch control. The Nayak sends small bands to raid Tranquebar.

- 1648 – Christian IV, patron of the colony dies. Danish East India Company bankrupt.

Abandonment and Isolation (1650–1669)

The lack of financial return led to repeated efforts by the major stockholders of the company to have it dissolved. The King, Christian IV, resisted these efforts until his death in 1648.[15] Two years later his son, Frederick II, abolished the company.[16]

Although the company had been abolished, the colony was a royal property, and still held by a garrison unaware of court developments back at home. As the number of Danes declined through desertions and illness, Portuguese and Portuguese-Indian natives where hired to garrison the fort until eventually, by 1655, Eskild Anderson Kongsbakke, was the commander and sole remaining Dane in Tranquebar.

An illiterate commoner, Kongsbakke was loyal to his country, and successfully held the fort under a Danish flag against successive sieges by the Nayak for non-payment of tribute, whilst seizing ships in the Bay of Bengal and using the proceeds of the sale of their goods to repair his defenses, build a wall around the town, and negotiate a settlement with the Nayak.

Kongsbakke's reports, sent back to Denmark via other European vessels, finally convinced the Danish government to relieve him. The frigate Færø was dispatched to India, commanded by Capt Sivardt Adelaer, with an official confirmation of his appointment as colony leader. It arrives May 1669 ending 29 years of isolation.

The Second Danish East India Company

Trade between Denmark and Tranquebar now resumed, a new Danish East India Company was formed, and several new commercial outposts where established, governed from Tranquebar: Oddeway Torre on the Malabar coast in 1696, and Dannemarksnagore at Gondalpara, southeast of Chandernagore in 1698. The settlement with the Nayak was confirmed and Tranquebar was permitted to expand to include three surrounding villages.

- 1752 – 1791 Calicut.

- October 1755 Frederiksnagore in Serampore, in present-day West Bengal.

- 9 June 1706 – Two Danish missionaries land in India – the first Protestant missionaries in India. They were not welcomed by their countrymen who suspected them of being spies.[17]

- November 1754 – Meeting of Danish officials in Tranquebar. Decision made to colonise the Andaman and Nicobar Islands for the purpose of planting pepper, cinnamon, sugarcane, coffee and cotton.

- December 1755 – Danish settlers arrive on Andaman Islands. Colony experiences outbreaks of Malaria that saw the settlement abandoned periodically until 1848, when it was abandoned for good. This sporadic occupation led to encroachments of other colonial powers onto the islands including Austria and Britain.[18]

- 1 January 1756 – The Nicobar Islands declared Danish property under the name Frederiksøerne (Frederick's Islands).

- 1763 Balasore (already occupied 1636–1643).

- In 1777, it was turned over to the government by the chartered company and became a Danish crown colony.

- In 1789, the Andaman Islands became a British possession.

Napoleonic Wars and Decline

During the Napoleonic Wars, the British attacked Danish shipping, and devastated the Danish East India Company's India trade. In May 1801 – August 1802 and 1808 – 20 September 1815 the British even occupied Dansborg and Frederiksnagore.

The Danish colonies went into decline, and the British ultimately took possession of them, making them part of British India: Serampore was sold to the British in 1839, and Tranquebar and most minor settlements in 1845 (11 October 1845 Frederiksnagore sold; 7 November 1845 other continental Danish India settlements sold); on 16 October 1868 all Danish rights to the Nicobar Islands, which since 1848 had been gradually abandoned, were sold to Britain.

Legacy

After the Danish colony of Tranquebar was ceded to the British it subsequently lost its special trading status and rapidly dwindled in importance.[19] Now primarily a fishing village, the legacy of the Dano-Norwegian colonial presence is entirely local, but can be seen in the architecture of the small town that lies within the boundares of the old (and long gone) city walls.[20] In fact, journalist Sam Miller describes the town as the most recognisably European of the former colonial settlements.[21]

Although only a handful of colonial buildings can be definitely dated to the Danish era, many of the town's residential buildings are in classical styles that would not be dissimilar to those of the era, and which contribute to the historic atmosphere. The remaining Danish buildings include a gateway inscribed with a Danish Royal Seal, a number of colonial bungalows, two churches and principally – the Dansborg Fort, constructed in 1620. The Dansburg Fort was declared a protected monument by the Government of Tamil Nadu in 1977 and now houses a museum dedicated to the Danes in India.

There are no known descendants of the Danish settlers in or around the town. Since 2001, Danes have been active in mobilising volunteers and government agencies to both purchase and restore Danish colonial buildings in Tranquebar. St. Olav's Church, Serampore still stands.

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Rasmussen, Peter Ravn (1996). "Tranquebar: The Danish East India Company 1616–1669". University of Copenhagen.

- ↑ Felbæk, Ole (1990). Den danske Asienhandel 1616–1807: Værdi og Volumen. pp. 320–324.

- ↑ Magdalena, Naum; Nordin, Jonas, eds. (2013). Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity. Contributions To Global Historical Archaeology. 37. Springer. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4614-6201-9 – via SpringerLink.

Denmark and particularly Sweden struggled with upholding overseas colonies and recruiting settlers and staff willing to relocate.

- ↑ Poddar, Prem (2008). A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures: Continental Europe and Its Empires. Edinburgh University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7486-2394-5.

- ↑ FeldbæK, Ole (1986). "The Danish trading companies of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Scandinavian Economic History Review". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 34 (3): 204–218. doi:10.1080/03585522.1986.10408070.

- ↑ Bredscdorff, Asta (2009). The Trials and Travels of Willem Leyel: An Account of the Danish East India Company in TRanquebar, 1639-49. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculuanum Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-87-635-3023-1.

In 1616 Danish merchants began to speculate on how they might get a share of some of the huge profits to be made out of the East India trade.

- ↑ "The Coromandel Trade of the Danish East India Company, 1618-1649". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 37 (1): 43–44. 1989.

- ↑ Esther Fihl (2009). "Shipwrecked on the Coromandel:The first Indo–Danish contact, 1620". Review of Development and Change 14 (1&2): 19–40

- ↑ Larsen, Kay (1907). Volume 1 of Dansk-Ostindiske Koloniers historie: Trankebar. Jørgensen. pp. 167–169.

- ↑ Bredsdorff, Asta (2009). The Trials and Travels of Willem Leyel: An Account of the Danish East India Company in Tranquebar, 1639–48. Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-87-635-3023-1.

- ↑ Of the 18 ships that departed from Denmark between 1622 and 1637, only 7 returned. Kay Larsen: Trankebar, op.cit., p.30-31.

- ↑ Brdsgaard, Kjeld Erik (2001). China and Denmark: Relations Since 1674. NIAS Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-87-87062-71-8.

- ↑ Jeyaraj, Daniel (2006). "Trancquebar Colony: Indo-Danish Settlement". Bartholomus Ziegenbalg, the Father of Modern Protestant Mission: An Indian Assessment. ISPCK. pp. 10–27. ISBN 978-81-7214-920-8.

- ↑ Lach, Donald (1993). Trade, missions, literature, Volume 3. University of Chicago Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-226-46753-5.

- ↑ Feldbæk, Ole (1981). The Organization and Structure of the Danish East India, West India and Guinea Companies in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Leiden University Press. p. 140.

- ↑ Feldboek, Ole (1991). "The Danish Asia trade 1620–1807". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 39 (1): 3–27.

- ↑ Sharma, Suresh K. (2004). Leiden University Press. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-959-1.

- ↑ Kukreja, Dhiraj (1 September 2013). "Andaman and Nicobar Islands: A Security Challenge for India". Indian Defence Review.

- ↑ Grønseth, Kristian (2007). "A Little Piece of Denmark in India", The Space And Places Of A South Indian Town, And The Narratives Of Its Peoples. Norway: University of Oslo. p. 4.

After becoming part of British India Tranquebar (renamed by the British) lost its special trade privileges and rapidly dwindled in importance. Today it is mainly a fishing village surrounding a small town with historical buildings and ruins from the Danish era.

- ↑ Grønseth, Kristian (2007). "A Little Piece of Denmark in India", The Space And Places Of A South Indian Town, And The Narratives Of Its Peoples. Norway: University of Oslo. p. 10.

Tranquebar is different from Tarangambadi in almost every detail: Architecturally it resembles a European colony more than an Indian fishing village, the population is demographically different (the majority inside the city walls are Christian, and no fishermen live here) and the soundscape is less Indian than museum-like: Compared to Main Street a couple of hundred meters away, King Street is nearly silent.

- ↑ Miller, Sam (2014). A Strange Kind of Paradise. India: Hamish Hamilton. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-670-08538-5.

Indeed, the coastal village of Tranquebar is the most recognisably European of the former colonial settlements built by five nations: the British, the French, the Portuguese, the Dutch and the Danes.