Death of Benito Mussolini

|

This article is part of a series about Benito Mussolini |

|---|---|

| |

The death of Benito Mussolini, the deposed Italian fascist dictator, occurred on 28 April 1945, in the final days of World War II in Europe, when he was summarily executed by Italian Communists in the small village of Giulino di Mezzegra in northern Italy. The "official"[1] version of events is that Mussolini was shot by Walter Audisio, a communist partisan who used the nom de guerre of "Colonel Valerio". However, since the end of the war, the circumstances of Mussolini's death, and the identity of his killer, have been subjects of continuing confusion, dispute and controversy in Italy.

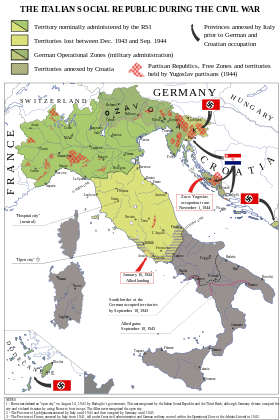

In 1940, Mussolini took his country into World War II on the side of Nazi Germany but soon met with military failure. By the autumn of 1943, he was reduced to being the leader of a German puppet state in northern Italy and was faced with the Allied advance from the south and an increasingly violent internal conflict with the partisans. In April 1945, with the Allies breaking through the last German defences in northern Italy and a general uprising of the partisans taking hold in the cities, Mussolini's situation became untenable. On 25 April he fled Milan, where he had been based, and tried to escape to the Swiss border. He and his mistress, Claretta Petacci, were captured on 27 April by local partisans near the village of Dongo on Lake Como. Mussolini and Petacci were shot the following afternoon, two days before Adolf Hitler's suicide.

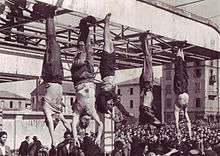

The bodies of Mussolini and Petacci were taken to Milan and left in a suburban square, the Piazzale Loreto, for a large angry crowd to insult and physically abuse. They were then hung upside down from a metal girder above a service station on the square. Initially, Mussolini was buried in an unmarked grave but, in 1946, his body was dug up and stolen by fascist supporters. Four months later it was recovered by the authorities who then kept it hidden for the next eleven years. Eventually, in 1957, his remains were allowed to be interred in the Mussolini family crypt in his home town of Predappio. His tomb has become a place of pilgrimage for neo-fascists and the anniversary of his death is marked by neo-fascist rallies.

In the post-war years, the "official" version of Mussolini's death has been questioned in Italy (but, generally, not internationally) in a way that has drawn comparison with the John F. Kennedy assassination conspiracy theories. Journalists, politicians and historians, doubting the veracity of Audisio's account, have put forward a wide variety of theories and speculation as to how Mussolini died and who was responsible. At least twelve different individuals have, at various times, been claimed to be the killer. These have included Luigi Longo and Sandro Pertini who subsequently became Secretary-General of the Italian Communist Party and President of Italy respectively. Several writers believe that Mussolini's death was part of a British special forces operation. The aim was supposedly to retrieve compromising "secret agreements" and correspondence with Winston Churchill that Mussolini had allegedly been carrying when he was captured. However, the "official" explanation, with Audisio as Mussolini's executioner, remains the most credible narrative.

Preceding events

Background

Mussolini had ruled Italy as its fascist leader since 1922 (and as dictator with the title Il Duce from 1925) and had taken the country into World War II on the side of Nazi Germany in June 1940.[2] Following the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943, Mussolini was deposed and put under arrest; Italy then switched sides and joined the Allies.[3] Later that year, he was rescued from prison in the Gran Sasso raid by German special forces and Hitler installed him as leader of the Italian Social Republic, a German puppet state set up in northern Italy and based at the town of Salò near Lake Garda.[4] By 1944, the "Salò Republic", as it came to be called, was threatened not only by the Allies advancing from the south but also internally by Italian anti-fascist partisans, in a brutal conflict that was to become known as the Italian civil war.[5]

Slowly fighting their way up the Italian peninsula, the Allies took Rome and then Florence in the summer of 1944 and later that year they began advancing into northern Italy. With the final collapse of the German army's Gothic Line in April 1945, total defeat for the Salò Republic and its German protectors was imminent.[6]

From mid-April Mussolini based himself in Milan, and he and his government took up residence in the city's Prefecture.[7] At the end of the month, the partisan leadership, the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale Alta Italia (CLNAI),[note 1] declared a general uprising in the main northern cities as the German forces retreated.[9] With the CLNAI's assumption of control in Milan and the German army in northern Italy about to surrender, Mussolini fled the city on 25 April and attempted to escape north to Switzerland.[9][10]

On the same day as Mussolini left Milan, the CNLAI declared:

The members of the fascist government and those fascist leaders who are guilty of having suppressed constitutional guarantees, destroyed the people's freedoms, created the fascist regime, compromised and betrayed the country, bringing it to the current catastrophe are to be punished with the penalty of death.[11]— CLNAI, Decree issued 25 April 1945

Capture and arrest

On 27 April 1945, Mussolini and his mistress Claretta Petacci, together with other fascist leaders, were travelling in a German convoy near the village of Dongo on the north western shore of Lake Como. A group of local communist partisans led by Pier Luigi Bellini delle Stelle and Urbano Lazzaro attacked the convoy and forced it to halt. The partisans recognised one Italian fascist leader in the convoy, but not Mussolini at this stage, and made the Germans hand over all the Italians in exchange for allowing the Germans to proceed. Eventually Mussolini was discovered slumped in one of the convoy vehicles.[12] Lazzaro later said that:

his face was like wax and his stare glassy, but somehow blind. I read utter exhaustion, but not fear...Mussolini seemed completely lacking in will, spiritually dead.[12]

The partisans arrested Mussolini and took him to Dongo, where he spent part of the night in the local barracks.[12] In all, over fifty fascist leaders and their families were found in the convoy and arrested by the partisans. Aside from Mussolini and Petacci, sixteen of the most prominent of them would be summarily shot in Dongo the following day and a further ten would be killed over two successive nights.[13]

Fighting was still going on in the area around Dongo. Fearing that Mussolini and Petacci might be rescued by fascist supporters, the partisans drove them, in the middle of the night, to a nearby farm of a peasant family named de Maria; they believed this would be a safe place to hold them. Mussolini and Petacci spent the rest of the night and most of the following day there.[14]

On the evening of Mussolini's capture, Sandro Pertini, the Socialist partisan leader in northern Italy, announced on Radio Milano:

The head of this association of delinquents, Mussolini, while yellow with rancour and fear and trying to cross the Swiss frontier, has been arrested. He must be handed over to a tribunal of the people so it can judge him quickly. We want this, even though we think an execution platoon is too much of an honour for this man. He would deserve to be killed like a mangy dog.[15]

Order to execute

Differing accounts exist of who made the decision that Mussolini should be summarily executed. Palmiro Togliatti, the Secretary-General of the Communist Party, claimed that he had ordered Mussolini's execution prior to his capture. Togliatti said he had done so by a radio message on 26 April 1945 with the words: "Only one thing is needed to decide that they [Mussolini and the other fascist leaders] must pay with their lives: the question of their identity".[16] He also claimed that he had given the order as deputy prime minister of the government in Rome and as leader of the Communist Party. Ivanoe Bonomi, the prime minister, later denied that this was said with his government's authority or approval.[16] A senior communist in Milan, Luigi Longo, said that the order came from the General Command of the partisan military units "in application of a CLNAI decision".[16] Longo subsequently gave a different story: he said that when he and Fermo Solari, a member of the Action Party (which was part of the CLNAI), heard the news of Mussolini's capture they immediately agreed that he should be summarily executed and Longo gave the order for it to be carried out.[16]

According to Leo Valiani, the Action Party representative on the CLNAI, the decision to execute Mussolini was taken on the night of 27/28 April by a group acting on behalf of the CLNAI comprising himself, Sandro Pertini, and the communists Emilio Sereni and Luigi Longo.[15] The CLNAI subsequently announced, on the day after his death, that Mussolini had been executed on its orders.[10]

In any event, Longo instructed a communist partisan of the General Command, Walter Audisio, to go immediately to Dongo to carry out the order. According to Longo, he did so with the words "go and shoot him".[17] Longo asked another partisan, Aldo Lampredi, to go as well because, according to Lampredi, Longo thought Audisio was "impudent, too inflexible and rash".[17]

Execution

Although several conflicting versions and theories of how Mussolini and Petacci died were put forward after the war, the account of Walter Audisio, or at least its essential components, remains the most credible and is sometimes referred to in Italy as the "official" version.[18][19][20]

It was largely confirmed by an account provided by Aldo Lampredi[21] and the "classical" narrative of the story was set out in books written in the 1960s by Bellini delle Stelle and Urbano Lazzaro, and the journalist Franco Bandini.[22] Although each of these accounts vary in detail, they are consistent on the main facts.[19]

Audisio and Lampredi left Milan for Dongo early on the morning of 28 April to carry out the orders Audisio had been given by Longo.[23][24] On arrival in Dongo, they met with Bellini delle Stelle, who was the local partisan commander, to arrange for Mussolini to be handed over to them.[23][24] Audisio used the nom de guerre of "Colonel Valerio" during his mission.[23][25] In the afternoon, he, with other partisans, including Aldo Lampredi and Michele Moretti, drove to the de Maria's farmhouse to collect Mussolini and Petacci.[26][27] After they were picked up, they drove a short distance to the village of Giulino de Mezzegra.[28] The vehicle pulled up at the entrance of the Villa Belmonte on a narrow road known as via XXIV maggio and Mussolini and Petacci were told to get out and stand by the villa's wall.[23][28][29] Audisio then shot them at 4:10 pm with a submachine gun borrowed from Moretti, his own gun having jammed.[23][27][30]

There were differences in Lampredi's account and that of Audisio. Audisio presented Mussolini as acting in a cowardly manner immediately prior to his death whereas Lampredi did not. Audisio said he read out a sentence of death, whereas Lampredi omitted this. Lampredi said that Mussolini's last words were "aim at my heart". In Audisio's account, Mussolini said nothing immediately prior to or during the execution.[31][32]

Differences also exist with the account given by others involved, including Lazzaro and Bellini delle Stelle. According to the latter, when he met Audisio in Dongo, Audisio asked for a list of the fascist prisoners that had been captured the previous day and marked Mussolini's and Petacci's names for execution. Bellini delle Stelle said he challenged Audisio as to why Petacci should be executed. Audisio replied that she had been Mussolini's adviser, had inspired his policies and was "just as responsible as he is". According to Bellini delle Stelle no other discussion or formalities concerning the decision to execute them took place.[33]

Audisio gave a different account. He claimed that on 28 April he convened a "war tribunal" in Dongo comprising Lampredi, Bellini delle Stelle, Michele Moretti and Lazzaro with himself as president. The tribunal condemned Mussolini and Petacci to death. There were no objections to any of the proposed executions.[33] Urbano Lazzaro later denied that such a tribunal had been convened and said:

I was convinced Mussolini deserved death...but there should have been a trial according to law. It was very barbarous.[33]

In a book he wrote in the 1970s, Audisio argued that the decision to execute Mussolini taken at the meeting in Dongo of the partisan leaders on 28 April constituted a valid judgment of a tribunal under Article 15 of the CNLAI's ordinance on the Constitution of Courts of War.[34] However, the lack of a judge or a Commissario di Guerra (required by the ordinance to be present) casts doubt on this assertion.[35][note 2]

Subsequent events

During his dictatorship, representations of Mussolini's body — for example pictures of him engaged in physical labour either bare-chested or half-naked — formed a central part of fascist propaganda. His body remained a potent symbol after his death, causing it to be either revered by supporters or treated with contempt and disrespect by opponents, and assuming a broader political significance.[37][38]

Piazzale Loreto

In the evening of 28 April, the bodies of Mussolini, Petacci, and the other executed Fascists were loaded onto a van and trucked south to Milan. On arriving in the city in the early hours of 29 April, they were dumped on the ground in the Piazzale Loreto, a suburban square near the main railway station.[39][40] The choice of location was deliberate. Fifteen partisans had been shot there in August 1944 in retaliation for partisan attacks and Allied bombing raids, and their bodies had then been left on public display. At the time, Mussolini is said to have remarked "for the blood of Piazzale Loreto, we shall pay dearly".[40]

Their bodies were left in a heap, and by 9 am a considerable crowd had gathered. The corpses were pelted with vegetables, spat at, urinated on, shot at and kicked; Mussolini's face was disfigured by beatings.[41][42] An American eye witness described the crowd as "sinister, depraved, out of control".[42] After a while, the bodies were hoisted up on to the metal girder framework of a half-built Standard Oil service station, and hung upside down on meat hooks.[41][42][43] This mode of hanging had been used in northern Italy since medieval times to stress the "infamy" of the hanged. However, the reason given by those involved in hanging Mussolini and the others in this way was to protect the bodies from the mob. Movie footage of what happened appears to confirm that to be the case.[44]

Morgue and autopsy

At about 2 pm, the American military authorities, who had arrived in the city, ordered that the bodies be taken down and delivered to the city morgue for autopsies to be carried out. A US army cameraman took photographs of the bodies for publication, including one with Mussolini and Petacci positioned in a macabre pose as though they were arm-in-arm.[45]

On 30 April, an autopsy was carried out on Mussolini at the Institute of Legal Medicine in Milan. One version of the subsequent report indicated that he had been shot with nine bullets, while another version specified seven bullets. Four bullets near the heart were given as the cause of death. The calibres of the bullets were not identified.[46] Samples of Mussolini's brain were taken and sent to America for analysis. The intention was to prove the hypothesis that syphilis had caused insanity in him, but nothing resulted from the analysis;[47] no evidence of syphilis was found on his body either. No autopsy was carried out on Petacci.[48]

Interment and theft of corpse

After his death and the display of his corpse in Milan, Mussolini was buried in an unmarked grave in the Musocco cemetery, to the north of the city. On Easter Sunday 1946, Mussolini's body was located and dug up by a young fascist, Domenico Leccisi, and two friends.[49] Over a period of sixteen weeks it was moved from place to place — the hiding places included a villa, a monastery and a convent — while the authorities searched for it.[37] Eventually, in August, the body (with a leg missing) was tracked down to the Certosa di Pavia, a monastery not far from Milan. Two Franciscan friars were charged with assisting Leccisi hide the body.[49][50]

The authorities then arranged for the body to be hidden at a Capuchin monastery in the small town of Cerro Maggiore where it remained for the next eleven years. The whereabouts of the body was kept a secret, even from Mussolini's family.[51] This remained the position until May 1957, when the newly appointed Prime Minister, Adone Zoli, agreed to Mussolini's re-interment at his place of birth in Predappio in Romagna. Zoli was reliant on the far right (including Leccisi himself, who was now a neo-fascist party deputy) to support him in Parliament. He also came from Predappio and knew Mussolini's widow, Rachele, well.[52]

Tomb and anniversary of death

The re-interment in the Mussolini family crypt in Predappio was carried out on 1 September 1957, with supporters present giving the fascist salute. Mussolini was laid to rest in a large stone sarcophagus.[note 3] The tomb is decorated with fascist symbols and contains a large marble head of Mussolini. In front of the tomb is a register for visitors paying their respects to sign. The tomb has become a neo-fascist place of pilgrimage. The numbers signing the tomb's register range from dozens to hundreds per day, with thousands signing on certain anniversaries; almost all the comments left are supportive of Mussolini.[52]

The anniversary of Mussolini's death on 28 April has become one of three dates neo-fascist supporters mark with major rallies. In Predappio, a march takes place between the centre of town and the cemetery. The event usually attracts supporters in the thousands and includes speeches, songs and people giving the fascist salute.[54]

Post-war controversy

Outside of Italy, Audisio's version of how Mussolini was executed has largely been accepted and is uncontroversial.[55] However, within Italy, the subject has been a matter of extensive debate and dispute since the late 1940s to the present and a variety of theories of how Mussolini died has proliferated.[10][55] At least 12 different individuals have been identified at various times as being responsible for carrying out the shooting.[55] Comparisons have been made with the John F. Kennedy assassination conspiracy theories,[10] and it has been described as the Italian equivalent of that speculation.[55]

Reception of Audisio's version

Until 1947, Audisio's involvement was kept a secret, and in the earliest descriptions of the events (in a series of articles in the Communist Party newspaper L'Unità in late 1945) the person who carried out the shootings was only referred to as "Colonnello Valerio".[56]

Audisio was first named in a series of articles in the newspaper Il Tempo in March 1947 and the Communist Party subsequently confirmed Audisio's involvement. Audisio himself did not speak publicly about it until he published his account in a series of five articles in L'Unità later that month (and repeated in a book that Audisio later wrote which was published in 1975, two years after his death).[56] Other versions of the story were also published, including, in the 1960s, two books setting out the "classical" account of the story: Dongo, la fine di Mussolini by Lazzaro and Bellini delle Stelle and Le ultime 95 ore di Mussolini by journalist Franco Bandini.[22]

Before long, it was noted that there were discrepancies between Audisio's original story published in L'Unità, subsequent versions that he provided and the versions of events provided by others. Although his account most probably is built around the facts, it was certainly embellished.[57] The discrepancies and obvious exaggerations, coupled with the belief that the Communist Party had selected him to claim responsibility for their own political purposes, led some in Italy to believe that his story was wholly or largely untrue.[57]

In 1996, a previously unpublished private account written in 1972 by Aldo Lampredi for the Communist Party's archives, appeared in L'Unità. In it, Lampredi confirmed the key facts of Audisio's story but without the embellishments. Lampredi was undoubtedly an eyewitness and, because he prepared his narrative for the private records of the Communist Party – and not for publication – it was perceived that he had no motivation other than to tell the truth. Furthermore, he had had a reputation for being reliable and trustworthy; he was also known to have disliked Audisio personally. For all these reasons it was seen as significant that he largely confirmed Audisio's account. After Lampredi's account was published, most, but not all, commentators were convinced of its veracity. The historian Giorgio Bocca commented that "it sweeps away all the bad novels constructed over 50 years on the end of the Duce of fascism...There was no possibility that the many ridiculous versions put about in these years were true...The truth is now unmistakably clear".[58]

Claims by Lazzaro

In his 1993 book Dongo: half a century of lies, the partisan leader Urbano Lazzaro repeated a claim he had made earlier that Luigi Longo and not Audisio, was "Colonnello Valerio". He also claimed that Mussolini was inadvertently wounded earlier in the day when Petacci tried to grab the gun of one of the partisans, who killed Petacci and Michele Moretti then shot dead Mussolini.[59][60][61]

The "British hypothesis"

There have been several claims that Britain's wartime covert operations unit, the Special Operations Executive (SOE), was responsible for Mussolini's death, and that it may have even been ordered by the British prime minister, Winston Churchill. Allegedly, it was part of a "cover up" to retrieve "secret agreements" and compromising correspondence between the two men, which Mussolini was carrying when he was captured by partisans. It is said that the correspondence included offers from Churchill of peace and territorial concessions in exchange for Mussolini persuading Hitler to join the western Allies in an alliance against the Soviet Union.[62][63] Proponents of this theory have included historians such as Renzo De Felice[64] and Pierre Milza[65] and journalists including Peter Tompkins[63] and Luciano Garibaldi;[66] however, the theory has been dismissed by many.[62][63][64]

In 1994 Bruno Lonati, a former partisan leader, published a book in which he claimed that he had shot Mussolini and he was accompanied on his mission by a British army officer called "John", who shot Petacci.[10][67] Journalist Peter Tompkins claimed to have established that "John" was Robert Maccarrone, a British SOE agent who had Sicilian ancestry. According to Lonati, he and "John" went to the de Maria farmhouse in the morning of 28 April and killed Mussolini and Petacci at about 11:00 am.[63][68] In 2004, the Italian state television channel, RAI, broadcast a documentary, co-produced by Tompkins, in which the theory was put forward. Lonati was interviewed for the documentary and claimed that when he arrived at the farmhouse:

Petacci was sitting on the bed and Mussolini was standing. "John" took me outside and told me his orders were to eliminate them both, because Petacci knew many things. I said I could not shoot Petacci, so John said he would shoot her himself, while making it quite clear that Mussolini however, had to be killed by an Italian.[63]

They took them out of the house and, at the corner of a nearby lane they were stood against a fence and shot. The documentary included an interview with Dorina Mazzola who said that her mother had seen the shooting. She also said that she herself had heard the shots and that she "looked at the clock, it was almost 11". The documentary went on to claim that the later shootings at the Villa Belmonte were subsequently staged as part of the "cover up".[63]

The theory has been criticised for lacking any serious evidence, particularly on the existence of the correspondence with Churchill.[62][69] Commenting on the RAI television documentary in 2004, Christopher Woods, researcher for the official history of the SOE, dismissed these claims saying that "it's just love of conspiracy-making".[63]

Other "earlier death" theories

Some, including most persistently the journalist Giorgio Pisanò, have claimed that Mussolini and Petacci were shot earlier in the day near the de Maria farmhouse and that the execution at Giulino de Mezzegra was staged with corpses.[70][71] The first to put this forward was Franco Bandini in 1978.[72]

Other theories

Other theories have included allegations not only that Luigi Longo, subsequently leader of the Communist Party in post-war Italy, but also Sandro Pertini, a future President of Italy, carried out the shootings. Others have claimed that Mussolini (or Mussolini and Petacci together) committed suicide with cyanide capsules.[73]

Notes

- ↑ The Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale Alta Italia (National Liberation Committee for Upper Italy) was the collective political-military leadership of the main partisan groups operating in northern Italy. It comprised representatives of the five main anti-fascist political parties: the Italian Communist Party, the Action Party, the Italian Socialist Party, the Christian Democrats and the Liberal Party. Each party controlled a partisan force, the largest being the Communists followed by the Action Party. The CLNAI was established in January 1944 to co-ordinate the activities of these partisan groups, but soon claimed to be the legitimate political authority in northern Italy. Although initially resistant, the Allies eventually recognised this claim and left the maintenance of public order in the liberated areas to the CLNAI. In March 1945 the CLNAI had 80,000 partisans under its control and this had risen to 250,000 by the end of April 1945.[8]

- ↑ After the war the family of Claretta Petacci began civil and criminal court cases against Walter Audisio for her unlawful killing. After a lengthy legal process, an investigating judge eventually closed the case in 1967 and acquitted Audisio of murder and embezzlement on the ground that the actions complained of occurred as an act of war against the Germans and the fascists during a period of enemy occupation.[36]

- ↑ As a post-script, in 1966 Mussolini's brain tissue samples, taken at the autopsy, were returned to his widow by St Elizabeth's psychiatric hospital in Washington DC, where they had been stored since 1945.[47] She placed the samples in a box in the tomb, leading the historian John Foot to comment that "finally, after nineteen years after his execution, Benito Mussolini's mortal and restless remains were back in one place, and in more or less one piece".[37] In 2009, it was reported that samples of Mussolini's brain and blood, stolen at the time of the autopsy, were offered for sale on eBay for 15,000 euros. eBay removed the listing shortly after it had been posted and no one had been able to bid. The hospital authorities said that all samples from the autopsy were destroyed in 1947.[53]

References

- ↑ Moseley 2004, p. 275

- ↑ BBC History

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2006, p. 51

- ↑ Quartermaine 2000, pp. 14, 21

- ↑ Payne 1996, p. 413

- ↑ Sharp Wells 2013, pp. 191–194

- ↑ Clark 2014, p. 320

- ↑ Clark 2014, pp. 375-378

- 1 2 Quartermaine 2000, pp. 130–131

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'Reilly 2001, p. 244

- ↑ Garibaldi 2004, pp. 79, 86

- 1 2 3 Bosworth 2014, p. 31

- ↑ Roncacci 2003, pp. 391, 403

- ↑ Neville 2014, p. 212

- 1 2 Moseley 2004, p. 282

- 1 2 3 4 Moseley 2004, pp. 280–281

- 1 2 Moseley 2004, pp. 281, 283, 302

- ↑ Cavalleri 2009, p. 11

- 1 2 Roncacci 2003, p. 404

- ↑ Moseley 2004, pp. 275–276, 290, 306

- ↑ Moseley 2004, p. 301

- 1 2 Di Bella 2004, p. 49

- 1 2 3 4 5 Audisio 1947

- 1 2 Moseley 2004, pp. 302–304

- ↑ Moseley 2004, p. 289

- ↑ Moseley 2004, pp. 290–292; 302–304

- 1 2 Bosworth 2014, pp. 31–32

- 1 2 Moseley 2004, pp. 290–291; 304

- ↑ Di Bella 2004, p. 50

- ↑ Moseley 2004, p. 304

- ↑ Moseley 2004, p. 304

- ↑ Luzzatto 2014, p. 54

- 1 2 3 Moseley 2004, p. 286

- ↑ Audisio 1975, p. 371

- ↑ Baima Bollone 2005, p. 165

- ↑ Baima Bollone 2005, p. 123

- 1 2 3 Foot 1999

- ↑ Luzzatto 2014, pp. 5–17

- ↑ Moseley 2004, pp. 311–313

- 1 2 Bosworth 2014, pp. 332–333

- 1 2 Luzzatto 2014, pp. 68–71

- 1 2 3 Moseley 2004, pp. 313–315

- ↑ Garibaldi 2004, p. 78

- ↑ Di Bella 2004, p. 51

- ↑ Luzzatto 2014, pp. 74–75

- ↑ Moseley 2004, p. 320

- 1 2 Bosworth 2014, p. 334

- ↑ Moseley 2004, p. 321

- 1 2 Moseley 2004, pp. 350–352

- ↑ Duggan 2013, pp. 428–429

- ↑ Moseley 2004, pp. 355–356

- 1 2 Duggan 2013, pp. 429–430

- ↑ Squires 2009

- ↑ Duggan 2013, p. 430

- 1 2 3 4 Moseley 2004, p. 275

- 1 2 Moseley 2004, p. 289

- 1 2 Moseley 2004, pp. 275, 289–293

- ↑ Moseley 2004, pp. 301–306

- ↑ Lazzaro 1993, p. 145ff.

- ↑ Moseley 2004, p. 299

- ↑ Hooper 2006

- 1 2 3 Bailey 2014, pp. 153–155

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Owen 2004

- 1 2 Bompard 1995

- ↑ Samuel 2010

- ↑ Garibaldi 2004, p. 138ff.

- ↑ Lonati 1994, p. 1ff.

- ↑ Tompkins 2001, pp. 340–354

- ↑ Moseley 2004, p. 341

- ↑ Bosworth 2014, p. 32

- ↑ Moseley 2004, pp. 297–298

- ↑ Bandini 1978, p. 1ff.

- ↑ Moseley 2004, p. 298

Bibliography

Books

- Audisio, Walter (1975). In nome del popolo italiano. Teti (Italy). ISBN 88-7039-085-3.

- Bailey, Roderick (2014). Target: Italy: The Secret War Against Mussolini 1940–1943. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-29920-1.

- Baima Bollone, Pierluigi (2005). Le ultime ore di Mussolini. Mondadori (Italy). ISBN 88-04-53487-7.

- Bandini, Franco (1978). Vita e morte segreta di Mussolini. Mondadori (Italy).

- Bellini delle Stelle, Pier Luigi; Lazzaro, Urbano (1962). Dongo ultima azione. Mondadori (Italy).

- Blinkhorn, Martin (2006). Mussolini and Fascist Italy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-85214-7.

- Bosworth, R. J. B. (2014). Mussolini. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84966-444-8.

- Cavalleri, Giorgio; et al. (2009). La fine. Gli ultimi giorni di Benito Mussolini nei documenti dei servizi segreti americani (1945–1946). Garzanti (Italy). ISBN 88-11-74092-4.

- Clark, Martin (2014). Modern Italy, 1871 to the Present. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-86603-9.

- Di Bella, Maria Pia (2004). "From Future to Past: A Duce's Trajectory". In Borneman, John. Death of the Father: An Anthropology of the End in Political Authority. Berghahn Books. pp. 33–62. ISBN 978-1-57181-111-0.

- Duggan, Christopher (2008). The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-618-35367-4.

- Duggan, Christopher (2013). Fascist Voices: An Intimate History of Mussolini's Italy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973078-0.

- Garibaldi, Luciano (2004). Mussolini: The Secrets of His Death. Enigma. ISBN 978-1-929631-23-0.

- Lazzaro, Urbano (1993). Dongo: mezzo secolo di menzogne. Mondadori. ISBN 88-04-36762-8.

- Lonati, Bruno Giovanni (1994). Quel 28 aprile. Mussolini e Claretta: la verità. Mursia (Italy). ISBN 88-425-1761-5.

- Luzzatto, Sergio (2014). The Body of Il Duce: Mussolini's Corpse and the Fortunes of Italy. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1-4668-8360-4.

- Moseley, Ray (2004). Mussolini: The Last 600 Days of Il Duce. Taylor Trade Publications. ISBN 978-1-58979-095-7.

- Neville, Peter (2014). Mussolini. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-61304-6.

- O'Reilly, Charles T. (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943–1945. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0195-7.

- Payne, Stanley G. (1996). A History of Fascism, 1914–1945. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-14873-7.

- Pisanò, Giorgio (1996). Gli ultimi cinque secondi di Mussolini. Il saggiatore (Italy). ISBN 88-428-0350-2.

- Quartermaine, Luisa (2000). Mussolini's Last Republic: Propaganda and Politics in the Italian Social Republic (R.S.I.) 1943–45. Intellect Books. ISBN 978-1-902454-08-5.

- Roncacci, Vittorio (2003). La calma apparente del lago. Como e il Comasco tra guerra e guerra civile 1940–1945. Macchione (Italy). ISBN 88-8340-164-6.

- Sharp Wells, Anne (2013). Historical Dictionary of World War II: The War in Germany and Italy. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7944-7.

- Tompkins, Peter (2001). Dalle carte segrete del Duce. Tropea (Italy). ISBN 88-4380-296-8.

Newspaper articles, journals and websites

- Audisio, Walter (March 1947). "Missione a Dongo". L'Unità.:

- "Missione a Dongo" (PDF). L'Unità. 25 March 1947. p. 1. Retrieved 6 November 2014.;

- "Missione a Dongo" (PDF). L'Unità. 25 March 1947. p. 2. Retrieved 6 November 2014.;

- "Solo a Como con 13 partigiani" (PDF). L'Unità. 26 March 1947. p. 1. Retrieved 6 November 2014.;

- "Solo a Como con 13 partigiani" (PDF). L'Unità. 26 March 1947. p. 2. Retrieved 6 November 2014.;

- "La corsa verso Dongo" (PDF). L'Unità. 27 March 1947. p. 1. Retrieved 6 November 2014.;

- "La corsa verso Dongo" (PDF). L'Unità. 27 March 1947. p. 2. Retrieved 6 November 2014.;

- "La fucilazione del dittatore" (PDF). L'Unità. 28 March 1947. p. 1. Retrieved 6 November 2014.;

- "La fucilazione del dittatore" (PDF). L'Unità. 28 March 1947. p. 2. Retrieved 6 November 2014.;

- "Epilogo a Piazzale Loreto" (PDF). L'Unità. 29 March 1947. p. 1. Retrieved 6 November 2014.;

- "Epilogo a Piazzale Loreto" (PDF). L'Unità. 29 March 1947. p. 2. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- BBC History. "Historic figures: Benito Mussolini (1883–1945)". BBC. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Bompard, Paul (16 October 1995). "Did Churchill kill Il Duce?". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Foot, John (1999). "The Dead Duce". History Today. 49 (8). Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Hooper, John (28 February 2006). "Urbano Lazzaro, The partisan who arrested Mussolini". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- Owen, Richard (28 August 2004). "Mussolini killed 'on Churchill's orders by British agents'". The Times. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Samuel, Henry (2 September 2010). "Winston Churchill 'ordered assassination of Mussolini to protect compromising letters'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Squires, Nick (21 November 2009). "Mussolini's brain 'stolen for sale on eBay'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Benito Mussolini. |