Dhananjoy Chatterjee

Dhananjoy Chatterjee (14 August 1965 – 14 August 2004) was born in Kuludihi, West Bengal, India and worked as a security guard in Kolkata.[1] He was the only person judicially executed in India in the twenty-first century so far for a crime not related to terrorism. The execution by hanging took place in Alipore Central Correctional Home, Kolkata, on 14 August 2004.[2][3] Dhananjoy had been charged with the crimes of rape and murder of Hetal Parekh, an 14-year-old school-girl, on 5 March 1990, in her third floor apartment in Bhawanipore, Kolkata.[4]

The execution stirred up many public controversies and attracted attention from media. Dhananjoy was convicted on the basis of circumstantial evidences only. He had consistently maintained his innocence throughout his trial and imprisonment,[5] which lasted for more than 14 years.[6]

Case summary

Hetal Parekh was a student of Welland Gouldsmith School at Bowbazar, Kolkata. She used to live with her parents and elder brother in a third floor flat of Anand Apartments in Bhawanipore. The Parekhs moved into this flat in 1987, soon after the construction of this building had been completed. There was an automatic elevator in the building, which used to be operated by a liftman from 8 am to 2 pm and 4 pm to 8 pm. Security and Investigation Bureau, a private security agency was entrusted with the security of the building. The agency used to engage security guards (casual workers) in three shifts a day. Dhananjoy was a security guard of this agency. He had worked in that building for about three years.[7]

On 5 March 1990, Dhananjoy performed security duty in Anand Apartments during the morning shift (6 am to 2 pm). Hetal left for her ICSE examination at about 7:30 am. After the examination, which was held at her own school, she returned home. In the afternoon, only Hetal and her mother were there in the flat. Hetal's father and brother were away in their shop at Bagri market.[7]

Hetal's mother went to visit the Lakshminarayan temple on Sarat Bose Road in the afternoon. The temple is only a ten minutes walk from Anand Apartments. After returning from the temple, she rang the calling bell of her flat a few times and banged on the door repeatedly, but no one opened the door. At her instruction, some servants of different flats broke the door open. Hetal was found lying dead near the door connecting the living room with the Parekh couple's bedroom. There was blood on her face and on the floor. Hetal's mother lifted Hetal's body and carried it to the ground floor by using the elevator. Two local doctors examined Hetal and declared her dead.[8] The liftman said that he had seen Dhananjoy walking down the stairs shortly before Hetal's mother had returned.[9]

The police was informed after Hetal's brother and father returned. Dhananjoy was not seen in the area after the murder had been discovered.[10] He became the focal point of police investigations. He was eventually arrested by the police from his village home at Kuludihi near Chhatna, Bankura, in the early hours of 12 May 1990.[11]

The case was investigated by the Detective Department of Kolkata Police. The chargesheet prepared by the police included the charges of rape, murder and the theft of a wrist watch. The trial took place in the second court of the Additional Sessions Judge at Alipore. Since there was no direct witness to the murder, the case hinged on circumstantial evidence only.[12] After the sessions court convicted Dhananjoy of all the offenses and sentenced him to death, the High Court at Calcutta and the Supreme Court of India upheld the conviction and the death sentence.[13]

Was Dhananjoy framed?

There may not have been a rape

Dhananjoy had been awarded the death penalty because the murder had been preceded by rape, which the Supreme Court regarded as a heinous combination of offenses, aggravated by the fact that as a security guard Dhananjoy had been in charge of the victim’s safety.[14] However, after his execution, several facts came to light that raise doubts about whether there had been a rape at all. The post-mortem report indicated fresh tear in the hymen and matted pubic hair, but absolutely no injury on the breasts, the genitalia or surrounding area. The victim’s brassiere and T-shirt were in place at the time of the post-mortem examination. The bulk of the 22 injuries suffered by the victim were in the face and the neck area (see figure).[15] The possibility that the intercourse had been a consensual act, which happened well before the murder, cannot be ruled out. Though semen was not detected in the vaginal swab in the forensic examination, it was detected in the victim's matted pubic hair and her pantie.[16] This finding is consistent with the possibility that the pantie was worn again after consensual sex. The revelation of this consensual sex could have been the background of a later altercation with the victim's mother.

The word 'rape' is not mentioned anywhere in the post-mortem report. In written reply to the question from the police, "was the victim raped", the autopsy doctor only stated that the victim was subjected to sexual intercourse before she had died.[17] However, while deposing in court, the autopsy doctor said "I mentioned about the rape in reply to the queries made by the police". He also said, "I had an impression while looking at exhibit 17 (post-mortem requisition containing queries from the police) that the deceased had been raped and killed".[18]

Dubious 'eye-witness' testimonies

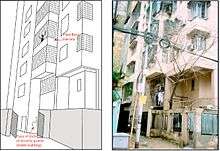

Dhananjoy had been linked to the crime through witness testimonies. Two main witness testimonies were from two security personnel, who purportedly conversed with Dhananjoy while he was leaning out of the balcony of the victim’s third floor flat at Anand Apartments and the witnesses were at the security guard's place of duty at the ground floor.[19] However, that balcony is not even visible from the guard’s place of duty, which is inside the building,[20] and it is not possible for anyone to lean out of the balcony enclosed in iron grills (see sketch).

The only other 'eyewitness', a liftman, contradicted what the prosecution claimed to be his statement to the police (e.g., he completely denied that he had taken Dhananjoy by lift to the third floor and saw him proceeding towards the victim’s flat). The liftman was declared a hostile witness at the behest of the prosecution.[21]

Dubious pieces of material evidence

One of the three pieces of material evidence used to link Dhananjoy to the crime scene was a neck-chain found there, which a servant of the opposite flat had claimed as his own.[22] He changed his story in Court and said that he had gifted the chain to Dhananjoy.[23] Another evidence was a 'stolen' watch 'seized' from Dhananjoy. The serial number of the watch was never matched with the purchase record, though the police was in touch with the shop that had sold it. The third piece of material evidence was a button found from the crime scene, and forensically linked with a shirt 'seized' from Dhananjoy under doubtful circumstances.[24] There was no independent witness of these 'seizures'. One of the witnesses could not be produced in court,[25] while the other one worked in a tea shop next to the police station and was known to have served tea to the police.[26] 'Seizures' from the crime scene were also dubious. The police was called more than three hours after the door of Hetal's flat was broken and her dead body was publicly discovered.[27] The body had been moved repeatedly and the crime scene had been trampled upon before the police arrived.[28]

Consistent claims of innocence

Dhananjoy had claimed repeatedly during his trial that he was completely innocent and that he had nothing to do with the murder, rape or theft.[29] He very strongly and repeatedly asserted all these in a video-recorded interview conducted for the documentary Right to Live by M.S. Sathyu in 1995. He maintained his innocence till the day of his execution.[30][31][32]

Miscarriage of justice

Some parts of the judgments of the High Court and the Supreme Court attract attention and baffle the reader. Some examples are given below.

The patent absurdity of the suggestion that a person proceeding to kill a girl would announce beforehand that he was going to her flat,[33] was pointed out by the defense counsel at the High Court. The Hon'ble judges observed: "Human conduct varies from person to person in a given situation. How a person would react to a particular situation depends on a variety of factor such as age, education, temperament, intelligence, presence of mind and moral upbringing."[34]

The defense counsel had also pointed out that it is extremely unlikely for an assailant, who has just committed rape and murder, to come out in the balcony of the flat only to respond to the call of someone at the ground floor.[19] The judges of the High Court explained: "It was not improbable that on the part of the accused to come out on the balcony and declare that he was coming down soon. In this situation he acted rather cleverly in dispelling the possible suspicion and the danger of PW 6 and PW 7 coming upstairs and preventing his escape."[35]

The High Court brushed aside the issue of Dhanajoy's unsoiled clothes even after a so-called rape and a messy murder, by speculating that he "must have removed" his clothes beforehand.[36] The Court was not bothered with follow-up questions, e.g., why the girl was patiently waiting while her attacker disrobed, why there was no evidence of her being gagged or tied up, why she would not raise an alarm, why she would not attack him with utensils or pieces of furniture, why she would not lock herself up in a room, how a button could be forcibly removed from the shirt Dhananjoy was no longer wearing,[24] and how would he manage the extra time to undress and dress up again.[37]

Dismissing the defense's submission that the complaint letters regarding Hetal's purported teasing by Dhananjoy had been seized after a long delay, the Supreme Court said: "In any event the seizure of the documents on 29.6.1990, after the appellant had been arrested only a couple of weeks earlier, would not go to show that the documents were either fabricated or were an afterthought."[38] There is a good amount of distortion of facts in this statement. Dhananjoy had been arrested on 12 May 1990, which was about seven weeks before the seizures.[39] Further, Dhananjoy's arrest should have had nothing to do with the seizures. If the complaint letter had been genuine, the matter would have come to light on the night of the murder itself, which took place seventeen weeks before the seizures.[4]

Hetal’s mother narrated in court what she described as Hetal’s complaint to her about teasing by Dhananjoy three days prior to the murder. This description was treated by the High Court as the dying declaration of the deceased,[40] even though the mother's failure to report this vital fact to the police[41] shows that it was probably an afterthought.

The Supreme Court judgment cited extraneous reasons for arriving at a decision on the sentencing of Dhananjoy Chatterjee. The judgment explicitly mentioned reports on "rising" rates of crime against women, as one of the considerations for its decision. It stressed the need for courts to "respond to the society's cry for justice against the criminals".[42] This court demonstrated that it was ready to respond to that cry. Such occurrences could give rise to the perception that the courts may have been persuaded by media reports, as there is no direct channel through which societal sentiments can reach the courts.

Nineteen years after this verdict by the Supreme Court of India, another bench of the Supreme Court observed that prima facie, the "criminal test"[43] had not been satisfied in the sentencing of Dhananjoy Chatterjee.[44]

Debates before execution

Dhananjoy's execution was scheduled on 25 June 2004 but it was stayed after his family petitioned the Supreme Court of India, and filed a mercy plea with the then President Late Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam.[45] On 26 June 2004 a campaign to ensure Dhananjoy's hanging was initiated. Mrs. Meera Bhattacharjee, wife of Mr. Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee the then Chief Minister of West Bengal, was at the forefront of this campaign. She made a passionate plea for Dhananjoy's hanging after providing details of the crime (e.g., that the rape was committed on a 14-year-old girl after she had been murdered)[45][46][47] that are contradicted by evidence on record.[4] Several individuals and human rights groups came forward to oppose the execution.[48][49] The mercy plea was finally rejected by the president on 4 August 2004.[50] The family refused to claim his body;[49] it was later cremated.[31]

The date of Dhananjoy's execution was fixed at a high-level meeting at the office of Jail Minister Biswanath Chowdhury.[51]

This was the first hanging in West Bengal since 21 August 1991, when murder convicts, Kartick Sil and Sukumar Burman, were hanged at Alipore Jail.[52][53][54]

The hangman

Nata Mullick, the hangman[55] who executed Dhananjoy demanded monthly stipends for three assistants including his son, as a precondition for carrying out the job of hanging.[56] He also sought and obtained a permanent government job for his grandson.[57][58] He reportedly sold pieces of the hanging noose for substantial price to people who believed that those pieces would bring good luck to them.[59][60] He became a sought-after person after the execution. He inaugurated blood donation camps, functions and even acted in a few jatras, or rural theatre.[58][60]

Demand for fresh investigation and exoneration

Since June 2015, new evidence that Dhananjoy may have been completely innocent has come to light.[24] Subsequently there has been a growing demand for a fresh investigation into the murder of Hetal Parekh and judicial execution of Dhananjoy Chatterjee.[1][61] Follow-up demands of posthumous exoneration of Dhananjoy Chatterjee and abolition of the death penalty are also being heard.[62][63] On 24 January 2016, such a demand was raised collectively by the people in a street meeting held in Chhatna, Bankura near Dhananjoy's native village.[64][65]

Eminent professors from ISI Kolkata and social activists , Debasish Sengupta, Prabal Choudhury, Paramesh Goswami have published their research work citing the dubious nature of the investigation and court statement on Dhananjay. The book is published by Guruchandali publication ,Kolkata.Titled as Adalat-Media-Samaj Ebong Dhananjayer Fashi (which can be loosely translated as Court-Media-Society and Dhananjay's Hanging), the work tries to detail the boundary conditions of the murder, the incompleteness and pre-bias of the investigation process and the role of media and social superstructures to influence judiciary systems of the state.[66]

See also

- Capital punishment in India

- List of offenders executed in India

- List of exonerated death row inmates

- Wrongful execution

- Innocence project

- Exculpatory evidence

- Miscarriage of justice

- List of miscarriage of justice cases

References

- 1 2 N., Jayaram (21 July 2015). "How India hanged a poor watchman whose guilt was far from established". scroll.in. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ↑ "Six convicts in death row in Bengal jails". The Times of India.

- ↑ "The Hindu : Front Page : Dhananjoy hanged". thehindu.com.

- 1 2 3 "Judgment in the case of Dhananjoy Chatterjee vs. State of West Bengal". A. S. Anand and N. P. Singh, JJ, para 1, page 226. Supreme Court of India. 11 January 1994. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "Right to Live". Documentary by M S Sathyu. PSBT India. 7 January 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ "The last hanging took 14 years after rape and murder".

- 1 2 Depositions of Yashomati Parekh (PW 3) and Nagardas Parekh (PW 4), recorded in pages 73 to 90 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Deposition of Yashomati Parekh (PW 3), recorded in pages 73 to 80 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Deposition of Ramdhan Yadav (PW 8), recorded in page 114 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Deposition of Nagardas Parekh (PW 4), recorded in pages 81 to 90 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Depositions of Gurupada Som (PW 28) and Salil Basu Chowdhury (PW 29), recorded in pages 172 to 179 and 180 to 186 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Judgment in Sessions Trial No. 1(11)90 of the Court of the Additional Sessions Judge, 2nd Court, Alipore, 12 August 1991, recorded in pages 247 to 307 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ "Judgment in the case of Dhananjoy Chatterjee vs. State of West Bengal". A.S. Anand and N. P. Singh, JJ. Supreme Court of India. 11 January 1994. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ↑ "Judgment in the case of Dhananjoy Chatterjee vs. State of West Bengal". A.S. Anand and N. P. Singh. Supreme Court of India. 11 January 1994. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Post-mortem report of Hetal Parekh (6 March 1990), recorded in pages 19-24 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Forensic report in Hetal Parekh murder case (27 October 1990), recorded in pages 398-405 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Hetal Parekh post-mortem requisition and answers to questions, recorded in pages 364-368 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Deposition of Dr. Dipankar Guha Roy (PW 20), recorded in pages 141-150 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- 1 2 Depositions of Pratap Chandra Pati (PW 6) and Dasarath Murmu (PW 7), recorded in pages 102 and 108 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Deposition of Santanau Basu (PW 2), recorded in page 69 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Deposition Ramdhan Yadav (PW 8), recorded in pages 114-119 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Depositions Bhavesh Parekh (PW 5) and Gurupada Som (PW 28), recorded in pages 91-99 and 172-179 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Deposition of Gouranga Chandra Raul (PW 11), recorded in pages 123-124 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- 1 2 3 "A re-analysis of the case of the murder of Hetal Parekh" (PDF). Debasis Sengupta and Probal Chaudhuri. 10 November 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Order sheet (9 March 1991) of Sessions Court, recorded in page 47 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Examination of the accused, recorded in pages 229-230 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ General Diary no. 514 of Bhawanipore Police Station (5 March 1990) and post mortem requisition (6 March 1990), recorded in pages 381 and 364 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Depositions of Bhavesh Parekh (PW 5) and Gurupada Som (PW 28), recorded in pages 92-93 and 172-179 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Examination of the accused, recorded in pages 189-246 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ "Dhananjoy's last words: I am innocent". Times of India. 15 August 2004. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- 1 2 Bhattacharya, Malabika (15 August 2004). "Dhananjoy hanged". The Hindu. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ "Dhananjoy pleaded innocence till last: Hangman". rediff.com. 14 August 2004. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ↑ Deposition of Dasarath Murmu (PW 7), recorded in page 107 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Judgment of the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991, 7 August 1992, Mukul Gopal Mukherji and J.N. Hore, JJ, page 27.

- ↑ Judgment of the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991, 7 August 1992, Mukul Gopal Mukherji and J.N. Hore, JJ, page 28.

- ↑ Judgment of the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991, 7 August 1992, Mukul Gopal Mukherji and J.N. Hore, JJ, pages 27, 31.

- ↑ "Dead Wrong: Why was Dhananjoy Chatterjee Hanged?" (PDF). page 11. PUDR. September 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ "Judgment in the case of Dhananjoy Chatterjee vs. State of West Bengal, para 10.1, page 232". Judgment in the case of Dhananjoy Chatterjee vs. State of West Bengal. Supreme Court of India. 11 January 1994. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ Deposition of Salil Basu Chowdhury, Investigating Officier (PW 29), recorded in page 182 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ Judgment of the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991, 7 August 1992, Mukul Gopal Mukherji and J.N. Hore, JJ, page 18-21.

- ↑ Deposition of Gurupada Som, Investigating Offiicer (PW 28) recorded in page 178 of the paper-book prepared for the High Court at Calcutta on Death Reference No. 3 of 1991 and Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991.

- ↑ "Judgment in the case of Dhananjoy Chatterjee vs. State of West Bengal". A.S. Anand and N.P. Singh, JJ, para 15, page 240. Supreme Court of India. 11 January 1994. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "One small step towards abolition?". Indian Constitutional Law and Philosophy. 12 November 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ "Judgment on Criminal Appeal nos. 362-363 of 2010". Shankar Kisanrao Khade vs State Of Maharashtra, 25 April 2013, para 22. Supreme Court of India. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- 1 2 Bhattacharyya, Malabika (30 June 2004). "Controversy rages over Dhananjoy issue". The Hindu. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ "Wife adds tears to Buddha's hang-him cry - Meera Bhattacharjee joins campaign to ensure condemned rapist 'gets what he deserves'". The Telegraph, Calcutta. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ "Dhananjay's execution demanded at open debate in city". Outlook. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ Chattopadhyay, Suhrid Sankar (14 August 2004). "The case of death sentence". Frontilne. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- 1 2 "India carries out rare execution". BBC News. 14 August 2004. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ Singh, Onkar (4 August 2004). "Kalam rejects Dhananjoy's mercy petition". rediff.com. Retrieved 2 December 2004.

- ↑ "Dhananjoy hanging: August 14, 0430 IST". rediff.com. 10 August 2004. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ "'I hanged my first victim when I was 16'". indianexpress.com.

- ↑ "The Telegraph - Calcutta : Metro". telegraphindia.com.

- ↑ https://www.amnesty.org/ar/library/asset/ASA20/039/1991/es/400235c5-f941-11dd-92e7-c59f81373cf2/asa200391991en.pdf

- ↑ "One Day From a Hangman's Life". Documentary by Joshy Joseph. Drik India. 22 June 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Debasish (20 June 2004). "Four days to hanging, Nata burgains". The Telegraph, Calcutta. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ↑ "Government job to hangman's grandson soon". sify.com. 8 August 2004. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- 1 2 Biswas, Soutik (3 June 2010). "A country in search of a hangman". BBC News. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "Calcutta hangman profiting from his noose". Taipei Times. 22 August 2004. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Hangman Mullick dies in Kolkata". Hindustan Times. 15 December 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "Execution of Dhananjoy Chatterjee erroneous: PUDR". The Hindu. 15 July 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ Editorial (25 July 2015). "The hanging question". Economic and Political Weekly. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Avijit (2 August 2015). "You were wrong, My Lords". The Telegraph, Calcutta. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ Bag, Rajendranath (25 January 2016). "Signature campaign demanding reinvestigation of Dhananjoy's hanging" (PDF). Ei Samay. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Bag, Rajendranath (25 January 2016). "Signature campaign demanding reinvestigation of Dhananjoy's hanging". Ei Samay. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Link, Book's (12 August 2016). "Adalat-Media-Samaj Ebong Dhananjayer Fashi". by ISI professors. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

External links

- Paper-book prepared for Criminal Appeal No. 272 of 1991 at the Calcutta High Court - website containing scanned copies of parts of the paper-book, with index

- "Murderers of Dhananjoy Hazir Ho! Abolish Death Penalty" - PUDR press release, 13 July 2015

- "Dhananjoy may once again appeal to SC" – article in Mid-day dated 4 August 2004

- "Dhananjoy to be hanged" – article in the Indian Express dated 5 August 2004 referring to his mercy petition being rejected by the President of India

- "Dhananjoy's parents plan last-ditch appeal" – article in sify.com dated 5 August 2004

- "Dhananjoy to be hanged on August 14" – article in sify.com dated 10 August 2004

- "Dhananjoy Chatterjee to be hanged on Aug 14" – article in indiainfo.com dated 10 August 2004

- "Rapist-murderer to be hanged in India" – MSNBC article dated 10 August 2004.

- "Dhananjoy Chatterjee to be hanged on Saturday" – article in the Deccan Herald on 11 August 2004

- "On death row Chatterjee gets a reprieve" – article in HTTabloid.com dated 11 August 2004

- "Dhananjoy Chatterjee cremated" – article in Indian Express dated 14 August 2004

- "Dhananjoy Chatterjee hanged in Kolkata jail" – article in indolink.com dated 14 August 2004

- "Demand for reinvestigation" – Kolkata dated 2 September 2016

- "Adalat-Media-Samaj Ebong Dhananjayer Fashi'" – Kolkata dated 12 August 2016