Dumb Witness

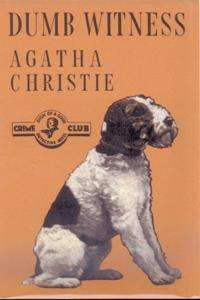

Dust-jacket illustration of the first UK edition | |

| Author | Agatha Christie |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Not known |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Crime novel |

| Publisher | Collins Crime Club |

Publication date | 5 July 1937 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 320 pp (first edition, hardcover) |

| Preceded by | Murder in the Mews |

| Followed by | Death on the Nile |

Dumb Witness is a detective fiction novel by British writer Agatha Christie, first published in the UK by the Collins Crime Club on 5 July 1937[1] and in the US by Dodd, Mead and Company later in the same year under the title of Poirot Loses a Client.[2][3] The UK edition retailed at seven shillings and sixpence (7/6)[4] and the US edition at $2.00.[3]

The book features the Belgian detective Hercule Poirot and is narrated by his friend Arthur Hastings. One novel published after this one features Hastings as narrator, 1975's Curtain: Poirot's Last Case.

Plot summary

Emily Arundell writes to Hercule Poirot because she believes she has been the victim of attempted murder. She is a wealthy spinster living in Berkshire. What she believes is attempted murder is seen by her household as her tripping over a ball left by her dog, the fox terrier Bob. When Poirot receives the letter, she has already died.

Her doctor says that she died of chronic liver problems. The woman's companion, Miss Minnie Lawson, is the unexpected beneficiary of a substantial fortune and the house, according to the will written while Emily recovered from that fall. Under the previous will, Miss Arundell's nephew, Charles Arundell, and nieces Theresa Arundell and Bella Tanios, would have inherited. This gives them all motive for the first attempted murder. While examining the house, under the pretense of buying it, Poirot discovers a nail covered with varnish and a small string tied to it at the top of the stairs. Before her death Miss Arundell had said something about Bob...dog...picture...ajar. Poirot concludes that this means a jar on which there is a picture of a dog that was left out all night — meaning that Bob could not have put the ball on the staircase because he had been out all night. Poirot concludes that Miss Arundell fell over a tripwire tied to the nail.

On the day Emily's last illness began, the Misses Tripp held a seance at Emily Arundell's home, with Minnie Lawson also in attendance. Both sisters say that when Miss Arundell spoke, a luminous aura came from her mouth, billowing like a spirit. Minnie Lawson similarly reports that a luminous haze appeared. Theresa and Charles want to contest the will. Bella agrees to join her cousins in this, but it is not pursued. At Miss Lawson's house, Poirot talks to the gardener and learns that Charles talked to him about his arsenic-based weed killer. The bottle is nearly empty – something that the gardener finds surprising. Miss Lawson recalls seeing someone through her bedroom mirror at the top of the stairs on the night of Miss Arundell's fall. The person was wearing a brooch with the initials, "TA", taken to be Theresa Arundell. After implying that he bullies her, Bella leaves her husband, Jacob. She goes to Miss Lawson, who hides her and the children at a hotel. Poirot directs Bella and her children to another hotel, and gives her his summary of Emily Arundell's death. Poirot fears a second murder; moving Bella is meant to protect the likely victim. The next day, Bella is found dead, by an overdose of chloral, a sleeping medication.

Poirot reveals to her surviving family and heiress how Emily Arundell was murdered and by whom. Poirot considered all as suspects to start. Theresa stole the arsenic, but could not bear to use it. She and her brother each suspected the other. Emily Arundell feared that her nephew, the only person bearing the Arundell name, had attempted to kill her, so she told him of the revised will. He was satisfied with stealing a small amount of cash. The brooch that Miss Lawson had seen through the mirror was Bella's with the initials "AT" for Arabella Tanios; they appeared as "TA" reversed in the mirror. Bella is the murderer. She never really loved her husband, and grew to hate him as the years rolled by. She wanted to separate from him and keep the children in England, but had no means. When her first attempt failed, she succeeded in her second attempt by inserting elemental phosphorus in one of the otherwise harmless capsules her aunt took for her liver troubles. Death by such poison causes liver failure, with symptoms like her disease, save for the phosphorescent breath, and a foul smell to it that her doctor missed. She was unaware her aunt changed her will, and faced a worse quandary. Bella took her own life after reading Poirot's summary of the case so far and yielding her children back to their father. She destroyed the papers, burning them in the fireplace to protect her children. Her husband is upset as he did love his wife, though he knows she obtained the chloral to kill him. Emily Arundell wanted no scandal, so Poirot concludes this is the best ending. Minnie Lawson, in her fluttering and caring way, decides to share her inherited wealth with Theresa, Charles, and Bella's children. Theresa marries Dr. Donaldson and is happy. Charles quickly spends his wealth. The dog Bob goes to Poirot, but it is Captain Hastings the dog prefers.

Characters

- Hercule Poirot: the renowned Belgian detective.

- Captain Arthur Hastings: narrator, Poirot's friend and friend to Bob the fox terrier.

- Emily Arundell: wealthy older woman who never married, owner of Little Green House; last survivor of five siblings, Matilda, Emily, Arabella, Thomas, and Agnes. Her sister Arabella and her brother Thomas each married later in life.

- Theresa Arundell: fashionable, attractive niece of Emily Arundell, not yet 30 years old; spent the capital she inherited at age 21 from her father; engaged to ambitious young doctor.

- Dr Rex Donaldson: Theresa's fiancé, and younger partner to Dr. Grainger.

- Charles Arundell: nephew of Emily Arundell and brother to Theresa, in his early thirties; son of Thomas Arundell and widowed Mrs Varley, found innocent of death of her first husband. He also spent the capital of his inheritance from his father.

- Bella Tanios: niece of Emily Arundell, cousin to Charles and Theresa; plain looks compared to her cousin Theresa, daughter of Arabella Arundell and Prof. Biggs, who taught chemistry at an English university.

- Dr Jacob Tanios: Bella's husband, of Greek descent, a physician practicing in Smyrna.

- Edward Tanios: young son of Bella & Jacob.

- Mary Tanios: young daughter of Bella & Jacob, about 7 years old.

- Ellen: long time member of Emily Arundell's household staff.

- Wilhelmina (Minnie) Lawson: Emily Arundell's companion for the last year, and in her final will, sole heiress.

- Isabel and Julia Tripp: two eccentric sisters and amateur spiritualists who share a home near Little Green House.

- Dr. Grainger: physician to Emily Arundell; in Market Basing since 1919.

- Miss Peabody: long time resident of village and friend of Emily Arundell, she knew all the Arundell siblings and shared her knowledge with Poirot.

- Bob: fox terrier belonging to Emily Arundell and the titular dumb witness.

Literary significance and reception

John Davy Hayward in the Times Literary Supplement (10 July 1937), while approving of Christie's work, commented on some length at what he felt was a central weakness of this book: "Who, in their senses, one feels, would use hammer and nails and varnish in the middle of the night within a few feet of an open door! – a door, moreover, that was deliberately left open at night for observation! And, incidentally, do ladies wear large broaches on their dressing gowns? .. These are small but tantalising points which it would not be worth raising in the work of a less distinguished writer than Mrs Christie; but they are worth recording, if only as a measure of curiosity and interest with which one approaches her problems and attempts to anticipate their solution."[5]

In The New York Times Book Review (26 September 1937), Kay Irvin wrote that "Agatha Christie can be depended upon to tell a good tale. Even when she is not doing her most brilliant work she holds her reader's attention, leads them on from clue to clue, and from error to error, until they come up with a smash against surprise in the end. She is not doing her most brilliant work in Poirot Loses A Client, but she has produced a much-better-than-average thriller nevertheless, and her plot has novelty, as it has sound mechanism, intriguing character types, and ingenuity.[6]

In The Observer's issue of 18 July 1937, "Torquemada" (Edward Powys Mathers) said, "usually after reading a Poirot story the reviewer begins to scheme for space in which to deal with it adequately; but Dumb Witness, the least of all the Poirot books, does not have this effect on me, though my sincere admiration for Agatha Christie is almost notorious. Apart from a certain baldness of plot and crudeness of characterisation on which this author seemed to have outgrown years ago, and apart from the fact that her quite pleasing dog has no testimony to give either way concerning the real as opposed to the attempted murder, her latest book betrays two main defects. In the first place, on receiving a delayed letter from a dead old lady Poirot blindly follows a little grey hunch. In the second place, it is all very well for Hastings not to see the significance of the brooch in the mirror, but for Poirot to miss it for so long is almost an affront to the would-be worshipper. Still, better a bad Christie than a good average."[7]

The Scotsman of 5 July 1937 started off with: "In Agatha Christie's novel there is a minor question of construction which might be raised." The reviewer then went on to outline the set-up of the plot up to the point where Poirot receives Emily Arundell's letter and then said, "Why should the story not have begun at this point? M. Poirot reconstructs it from here and the reader would probably have got more enjoyment out of it if he had not had a hint of the position already. But the detection is good, and the reader has no ground for complaint, for the real clue is dangled before his eyes several times, and because it seems a normal feature of another phenomenon than poisoning that he tends to ignore it. For this Agatha Christie deserves full marks." [8]

E.R. Punshon of The Guardian began his review column of 13 July 1937 by an overview comparison of the books in question that week (in addition to Dumb Witness, I'll be Judge, I'll be Jury by Milward Kennedy, Hamlet, Revenge! by Michael Innes, Dancers in Mourning by Margery Allingham and Careless Corpse by C. Daly King) when he said, "Only Mrs Christie keeps closer to the old tradition, and this time she adds much doggy lore and a terrier so fascinating that even Poirot himself is nearly driven from the centre of the stage." In the review proper, he went on to say that the dedication of the novel to Peter was, "a fact that in this dog-worshipping country is enough of itself to ensure success." He observed that Poirot, "shows all of his usual acumen; Captain Hastings – happily once more at Poirot's side – more than all his usual stupidity, and there is nothing left for the critic but to offer his usual tribute of praise to another of Mrs Christie's successes. She does indeed this sort of thing so superlatively well that one is ungratefully tempted to wish she would do something just a little well different, even if less well."[9]

In the Daily Mirror (8 July 1937), Mary Dell wrote: "Once I had started reading, I did not have to rely on Bob or his cleverness to keep me interested. This is Agatha Christie at her best." She concluded, "Here's a book that will keep all thriller fans happy from page one to page three hundred and something."[10]

Robert Barnard: "Not quite vintage for the period: none of the relations of the dead woman is particularly interesting, and the major clue is very obvious. The doggy stuff is rather embarrassing, though done with affection and knowledge. At the end the dog is given to Hastings – or possibly vice versa."[11]

References to other works

- Chapter 11: "Poirot's travellings in the East, as far as I knew, consisted of one journey to Syria extended to Iraq, and which occupied perhaps a few weeks". After solving a case in Syria by the request of his friend, Poirot decided to travel to Iraq before returning to England and, while in Iraq, was requested to solve a case, which he did and which is told in Christie's 1936 novel "Murder in Mesopotamia", after which Poirot returned to Syria and boarded Orient Express to return home and en route solved Murder on the Orient Express.

- In chapter 18 of the novel, Poirot gives a list of murderers from previous cases of his, more precisely Death in the Clouds (1935), The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), and The Mystery of the Blue Train (1928).

- In chapter 13 of the novel, Poirot discusses with Theresa why she is attracted to the steady and ambitious research doctor. She replies by asking why did Juliet fall for Romeo?, making a reference to the lovers in the play Romeo and Juliet by Shakespeare.

Possible errata

The son of Bella and Jacob Tanios is mentioned as Edward and, twice, as John in the novel. The boy is mentioned by name by his mother in Chapters 2, 16, 17 and by his father in Chapters 2 and 17 as well. At any other time, they are mentioned as "the children". At the very end of Chapter 16 in one print version, when Bella, her daughter Mary and Poirot are joined by Jacob Tanios and their son, Poirot asks Bella a question and she replies: "When do you return to Smyrna, madame?" "In a few weeks' time. My husband – ah! here is my husband and John with him."

At the start of Chapter 17, Jacob Tanios then calls his son John: "Here we are," he said, smiling to his wife. "John has been passionately thrilled by his first ride in the tube. He has always been in buses until today."

Other print versions have more switches between John and Edward (in Chapter 2 a few sentences apart, for example).

However, in the audiobook edition read by Hugh Fraser, the boy is always called Edward, even in those two instances where the print version has the wrong name. Thus they are termed errata. It is not clear when the errata were corrected for the audiobook.[12]

Also in the audio book, the title of Chapter 18 is A Cuckoo in the Nest, changed from A Nigger in the Woodpile, in early texts.[12] That change is more likely attributed to changing values as to accepted language, than considered errata.

History of the novel

Dumb Witness was based on a short story entitled The Incident of the Dog's Ball. This short story was lost for many years but found by the author's daughter in a crate of her personal effects, in 2004.[13] The Incident of the Dog's Ball was published in Britain in September 2009 in John Curran's Agatha Christie's Secret Notebooks: Fifty Years Of Mysteries. The short story was also published by The Strand Magazine in their tenth anniversary issue of the revived magazine in 2009.[14][15][16]

Quotes

Poirot on lying as needed to learn the facts, in conversation with Hastings in Chapter 26:

H: "More lies, I suppose?"

P: "You are really very offensive sometimes, Hastings. Anybody would think I enjoyed telling lies."

H: "I rather think you do. In fact, I'm sure of it."

P: "It is true that I sometimes compliment myself upon my ingenuity," Poirot confessed naively

Adaptations

Television

In 1996, the novel was adapted as part of the television series Agatha Christie's Poirot, starring David Suchet as Poirot. The adaptation made a number of notable changes to it, which included the following:

- The setting was changed from Berkshire to England's Lake District.

- Poirot visits the Arundell home before Emily dies, and not after; he does not use the pretense of buying it to examine the house. In addition, after learning of her fall, he influences her to change her will to favour Miss Lawson, and later advises her companion to share out her inheritance to the Arundell family after the court case.

- Charles Arundell is a motor-boat racer and a friend of Captain Hastings, who attempts to beat the water speed record, and uses his aunt to finance the attempts. His sister Theresa is changed from the vain, young, engaged woman in the novel to a middle-aged single woman.

- Bella Tanios does not leave on her own with the children, but is helped by Poirot and Hastings, to a safe place and does not get told to go to another place.

- No arsenic is stolen in the adaptation.

- The role of the dog, Bob, the dumb witness who is suspected of causing Emily's fall, is slightly altered in the television adaptation - in the novel the dog often left the ball on the landing, and the people of the house put it away, but on the night of Emily's fall the dog had been outside all night with the ball in a drawer. In the adaptation, the dog often takes the ball with him to his basket, never leaving it anywhere else, proving that when it was found on the stairs, it could not have been the dog's doing but must involve someone else; Bob was not outside the house when Emily fell in this adaptation.

- An additional murder was added into the adaptation - that of Dr Grainger. Whilst talking to Miss Lawson about Emily's death, he had suddenly realised the significance of the mist coming out of Emily as a sign, realising how she was poisoned with elemental phosphorus, but foolishly alerted Bella to his suspicions. Thus, Bella went to his room while he slept, and opened up an unlit room heater, flooding it with carbon monoxide, killing him as a result.

- When Poirot reveals his findings to all, Bella does not commit suicide; she is present with the others, and exposed as the murderer, rather than being given a summary of it by Poirot on her own.

The cast includes:

- Hugh Fraser as Hastings

- Ann Morrish as Emily Arundel

- Patrick Ryecart as Charles Arundel

- Kate Buffery as Theresa Arundel

- Paul Herzberg as Jacob Tanios

- Julia St. John as Bella Tanios

- Norma West as Wilhelmina Lawson

- Jonathan Newth as Dr. Grainger

Radio

BBC Radio 4 did a full cast adaptation of the novel in 2006, featuring John Moffatt as Hercule Poirot and Simon Williams as Captain Arthur Hastings. Music was composed by Tom Smail.[17]

The production was recorded for sale as an audio book on cassette or CD. Three editions of this BBC Radio Full Cast Drama were released in the UK and US markets, the latest being the January 2010 US edition on CD, ISBN 9781602838086.[18]

Graphic novel

Dumb Witness was released by HarperCollins as a graphic novel adaptation on 6 July 2009, adapted and illustrated by "Marek" (ISBN 0-00-729310-0).

Publication history

- 1937, Collins Crime Club (London), 5 July 1937, Hardcover, 320 pp

- 1938, Dodd Mead and Company (New York), 1937, Hardcover, 302 pp

- 1945, Avon Books, Paperback, 260 pp (Avon number 70)

- 1949, Pan Books, Paperback, 250 pp (Pan number 82)

- 1958, Fontana Books (Imprint of HarperCollins), Paperback, 255 pp

- 1965, Dell Books, Paperback, 252 pp

- 1969, Pan Books, Paperback, 218 pp

- 1973, Ulverscroft Large-print Edition, Hardcover, 454 pp

- 1975, Fontana Books, Paperback, 255 pp

- 2007, Poirot Facsimile Edition (Facsimile of 1937 UK First Edition), HarperCollins, 3 January 2007, Hardback, ISBN 0-00-723446-5

In addition to those listed above, thirteen paperbacks issued from July 1969 (Macmillan UK edition) to June 2011 (William Morrow US edition ISBN 9780062073754) are shown at Fantastic Fiction. The most recent hardback edition was issued in April 2013 for the US market by Center Point ISBN 9781611736830.[18]

The book is in continuous publication, and in several forms. Two Kindle editions have been issued: one in January 2005 by William Morrow Paperbacks (ISBN B000FC2RRM) and again in October 2010 by HarperCollins (ISBN B0046RE5CW). Four audio editions for the UK and US markets are listed, from August 2002, all read by Hugh Fraser by HarperCollins Audiobooks in the UK, and by BBC Audiobooks America and Audio Partners, The Mystery Masters ISBN 9781572705135 February 2006 in the US.[18]

The book was first serialised in the US in The Saturday Evening Post in seven instalments from 7 November (Volume 209, Number 19) to 19 December 1936 (Volume 209, Number 25) under the title Poirot Loses a Client with illustrations by Henry Raleigh.

In the UK, the novel was serialised as an abridged version in the weekly Women's Pictorial magazine in seven instalments from 20 February (Volume 33, Number 841) to 3 April 1937 (Volume 33, Number 847) under the title Mystery of Littlegreen House. There were no chapter divisions and all of the instalments carried illustrations by "Raleigh".[19]

References

- ↑ The Observer, 4 July 1937 (p. 6)

- ↑ John Cooper and B.A. Pyke. Detective Fiction – the collector's guide: Second Edition (Pages 82 and 86) Scholar Press. 1994. ISBN 0-85967-991-8

- 1 2 American Tribute to Agatha Christie

- ↑ Chris Peers, Ralph Spurrier and Jamie Sturgeon (March 1999). Collins Crime Club – A checklist of First Editions (Second ed.). Dragonby Press. p. 15.

- ↑ The Times Literary Supplement, 10 July 1937 (p. 511)

- ↑ The New York Times Book Review, 26 September 1937 (p. 26)

- ↑ The Observer, 18 July 1937 (Page 8)

- ↑ The Scotsman, 5 July 1937 (p. 15)

- ↑ The Guardian, 13 July 1937 (p. 7)

- ↑ Daily Mirror, 8 July 1937 (p. 24)

- ↑ Barnard, Robert. A Talent to Deceive – an appreciation of Agatha Christie – Revised edition (p. 192). Fontana Books, 1990. ISBN 0-00-637474-3

- 1 2 Agatha Christie; Hugh Fraser (2002) [1937]. Dumb Witness. Sound Library Chivers North America (CD). London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-7927-5292-9.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maeve; Katie Allen (5 June 2009). "Two unpublished Poirot short stories found in Agatha Christie's holiday home". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Burton Frierson (10 November 2009). "Lost Agatha Christie story to be published". Reuters. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ "The Strand Magazine's Online Shop: Tenth Anniversary Issue of The Strand". Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Chris Willis (2006). "The Story of The Strand". History: 1891 to 1950, December 1998 restart. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ "Biography: Tom Smail". 5 February 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Dumb Witness (Hercule Poirot, book 16)". Fantastic Fiction. 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ Holdings at the British Library (Newspapers – Colindale). Shelfmark: NPL LON TB12.

External links

- Dumb Witness at the official Agatha Christie website

- Dumb Witness (1996) at the Internet Movie Database