Edward Wilmot Blyden

| Edward Wilmot Blyden | |

|---|---|

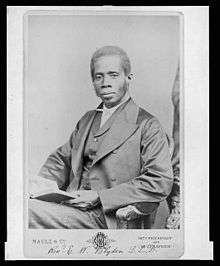

c 1860s, London | |

| Born |

3 August 1832 St Thomas, Danish West Indies (now the US Virgin Islands) |

| Died |

7 February 1912 (aged 79) Freetown, Sierra Leone |

| Nationality | Liberian |

| Other names | Eddy, Ed |

| Citizenship | Danish West Indies |

| Occupation | educator, writer, diplomat, politician |

| Known for |

"Father of Pan-Africanism" Liberian ambassador and politician |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Yates |

| Partner(s) | Anna Erskine |

| Children | Pay'ton Blyden |

Edward Wilmot Blyden (3 August 1832 – 7 February 1912), the father of pan-Africanism, was an educator, writer, diplomat, and politician primarily in Liberia. Born in the West Indies, he joined the free black immigrants to the region from the United States; he also taught for five years in the British West African colony of Sierra Leone in the early 20th century. His writings on pan-Africanism were influential in both colonies, which were started during the slavery years for the resettlement of free blacks from the United States and Great Britain. His writings attracted attention in the sponsoring countries as well. He felt that Zionism was a model for what he called Ethiopianism, and that African Americans could return to Africa and redeem it. He believed political independence to be a prerequisite for economic independence, and argued that Africans must counter the neocolonial policies of former colonial forces.[1]

Blyden was recognised in his youth for his talents and drive; he was educated and mentored by John Knox, an American Protestant minister in St Thomas, Danish West Indies, who encouraged him to continue his education in the United States. Blyden was refused admission in 1850 to three Northern theological seminaries, including Rutgers’ Theological College in New Jersey, because of his race.[2] Knox encouraged him to go to Liberia, the colony set up for freedmen by the American Colonization Society; Blyden emigrated that year, in 1850, and made his career and life there. He married into a prominent family and soon started working as a journalist.

Early life and education

.jpg)

Blyden was born on 3 August 1832 in St Thomas, Danish West Indies (now known as the US Virgin Islands), to Free Black parents who claimed descent from the Igbo of the area of present-day Nigeria.[3][4] Between 1842 and 1845 the family lived in Porto Bello, Venezuela, where Blyden discovered a facility for languages, becoming fluent in Spanish.[5]

According to the historian Hollis R. Lynch, in 1845 Blyden met the Reverend John P. Knox, a white American, who became pastor of the St. Thomas Protestant Dutch Reformed Church.[5] Blyden and his family lived near the church, and Knox was impressed with the studious, intelligent boy. Knox became his mentor, encouraging Blyden's considerable aptitude for oratory and literature. Mainly because of his close association with Knox, the young Blyden decided to become a minister, which his parents encouraged.[5]

In May 1850, Blyden, accompanied by Reverend Knox's wife, went to the United States to enroll in Rutgers Theological College, Knox's alma mater. He was refused admission due to his race. Efforts to enroll him in two other theological colleges also failed. Knox encouraged Blyden to go to Liberia, the colony set up in the 1830s by the American Colonization Society (ACS) in West Africa, where he thought Blyden would be able to use his talents.[6] Later in 1850, Blyden sailed to Liberia. He soon became deeply involved in its development.

Marriage and family

Blyden married Sarah Yates, an Americo-Liberian from the prominent Yates family. She was the daughter of Hilary Yates and niece of Beverly Page Yates, who served as vice-president of Liberia from 1856 to 1860 under President Stephen Allen Benson. She and Blyden had three children together.

Later while living in Freetown, Sierra Leone, Blyden had a long-term relationship with Anna Erskine, an African-American woman from Louisiana. She was a granddaughter of James Spriggs-Payne, who was twice elected as the President of Liberia. Erskine and Blyden had five children together, and his direct descendants living in Sierra Leone are from this union. They have been considered part of the Krio population. Some Blyden descendants continue to live in Freetown, among them Sylvia Blyden, publisher of the Awareness Times.

Blyden died on 7 February 1912 in Freetown, Sierra Leone, where he was buried at Racecourse Cemetery. In honour of him, the 20th-century Pan-Africanist George Padmore named his daughter Blyden.[7]

Career

Emigrating to Liberia in 1850, Blyden soon was working in journalism. From 1855 to 1856, he edited the Liberia Herald and wrote the column "A Voice From Bleeding Africa". He also spent time in British colonies in West Africa, particularly Nigeria and Sierra Leone, writing for early newspapers in both colonies. He was also serving as editor at The Negro and The African World. He maintained ties with the American Colonization Society and published in their African Repository and Colonial Journal.

In 1861, Blyden became professor of Greek and Latin at Liberia College. He was selected as president of the college, serving 1880–1884 during a period of expansion.

As a diplomat, Blyden served as an ambassador for Liberia to Britain and France. He also traveled to the United States, where he spoke to major black churches about his work in Africa. Blyden believed that Black Americans could end their suffering of racial discrimination by returning to Africa and helping to develop it. He was criticised by African Americans who wanted to gain full civil rights in their birth nation of the United States and did not identify with Africa.[8]

In suggesting a redemptive role for African Americans in Africa through what he called Ethiopianism, Blyden likened their suffering in the diaspora to that of the Jews; he supported the Zionist project of Jews returning to Palestine.[9] Later in life, Blyden became involved in Islam, and concluded that it was a more "African" religion than Christianity for African Americans and Americo-Liberians.

Participating in the development of the country, Blyden was appointed the Liberian Secretary of State (1862–64). He was later appointed as Minister of the Interior (1880–82). Blyden contested the 1885 presidential election for the Republican Party, but lost to incumbent Hilary R. W. Johnson.

From 1901–06, Blyden directed the education of Muslims at an institution in Sierra Leone, where he lived in Freetown. This is when he had his relationship with Anna Erskine; they had several children together. He became passionate about Islam during this period, recommending it to African Americans as the major religion most in keeping with their historic roots in Africa.[9]

Writings

As a writer, Blyden is regarded widely as the "father of Pan-Africanism" and is noted as one of the first people to articulate a notion of "African Personality" and the uniqueness of "African race".[1] His ideas have influenced many twentieth century figures including Marcus Garvey, George Padmore and Kwame Nkrumah.[1] His major work, Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race (1887), promoted the idea that practising Islam was more unifying and fulfilling for Africans than Christianity. He argues that the latter was introduced chiefly by European colonizers. He believed it had a demoralising effect, although he continued to be a Christian. He thought Islam was more authentically African, as it had been brought to sub-Saharan areas by people from North Africa.

His book was controversial in Great Britain, both for its subject and because many people at first did not believe that a black African had written it. In later printings, Blyden included his photograph as the frontispiece.[10]

Blyden wrote:

"'Let us do away with the sentiment of Race. Let us do away with out African personality and be lost, if possible, in another Race.' This is as wise or as philosophical as to say, let us do away with gravitation, with heat and cold and sunshine and rain. Of course, the Race in which these persons would be absorbed is the dominant race, before which, in cringing self-surrender and ignoble self-suppression they lie in prostrate admiration."

Due to his religious affiliations, in the late 19th century Blyden publicly supported the creation of a Jewish state in Israel; he praised Theodore Herzl as the creator of "that marvelous movement called Zionism."[11]

Works

Books

- "The Call of Providence to the Descendants of Africa in America", A Discourse Delivered to Coloured Congregations in the Cities of New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Harrisburg, during the Summer of 1862, in Liberia's Offering: Being Addresses, Sermons, etc., New York: John A. Gray, 1862.

- Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race, London, W. B. Whittingham & Co., 1887; 2nd Edition 1888; University of Edinburgh Press, 3rd Edition, 1967; reprint of 1888 edition, Baltimore, Maryland: Black Classic Press, 1994 (edition on Googlebooks).

- African Life and Customs, London: C. M. Phillips, 1908; reprint Baltimore, Maryland: Black Classic Press, 1994.

- West Africa Before Europe: and Other Addresses, Delivered in England in 1901 and 1903, London: C. M. Phillips, 1905.

Essays and speeches

- "Africa for the Africans," African Repository and Colonial Journal, Washington, DC: January 1872.

- "The Call of Providence to the Descendants of Africa in America", A Discourse Delivered to Coloured Congregations in the Cities of New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Harrisburg, during the Summer of 1862, in Liberia's Offering: Being Addresses, Sermons, etc., New York: John A. Gray, 1862.

- "The Elements of Permanent Influence", Discourse Delivered at the 15th St. Presbyterian Church, Washington, DC, Sunday, 16 February 1890, Washington, DC: R. L. Pendleton (published by request), 1890 (hosted on Virtual Museum of Edward W. Blyden).

- "Liberia as a Means, Not an End", Liberian Independence Oration: 26 July 1867; African Repository and Colonial Journal, Washington, DC: November 1867.

- "The Negro in Ancient History, Liberia: Past, Present, and Future," Methodist Quarterly Review, Washington, DC: M'Gill & Witherow Printer.

- "The Origin and Purpose of African Colonization", A Discourse Delivered at the 66th Anniversary of the American Colonization Society, Washington, DC, 14 January 1883, Washington, 1883.

- E. W. Blyden M.A., Report on the Falaba Expedition 1872, Addressed to His Excellency Governor J. Pope Hennessy, C.M.G., Published by authority Freetown, Sierra Leone. Printed at Government Office, 1872.

- "Liberia at the American Centennial", Methodist Quarterly Review, July 1877.

- "America in Africa," Christian Advocate I, 28 July 1898, II, 4 August 1898.

- "The Negro in the United States," A.M.E. Church Review, January 1900.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Martin, G. (2012-12-23). African Political Thought. Springer. ISBN 9781137062055.

- ↑ "Blyden, Edward Wilmot (1832-1912) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- ↑ "Edward Wilmot Blyden". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ↑ "Edward Wilmot Blyden:- Father of Pan Africanism (August 3, 1832 to February 7, 1912)". Awareness Times (Sierra Leone). 2 August 2006.

- 1 2 3 Hollis R. Lynch, Edward Wilmot Blyden: Pan-Negro Patriot, 1832–1912, New York: Oxford University Press, 1967, p. 4.

- ↑ Lynch, Edward Wilmot Blyden, 1967.

- ↑ Hooker, James Ralph, Black Revolutionary: George Padmore's Path from Communism to Pan-Africanism, London: Pall Mall Press, 1967; New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1967, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Runoko Rashidi post, "Africa for the Africans", The Global African Community – personal website, 1998, accessed 3 January 2011.

- 1 2 Black Zion : African American Religious Encounters with Judaism, edited by Yvonne Chireau, Nathaniel Deutsch; Oxford University Press, 1999, Google eBook, p. 15

- ↑ Eluemuno-Chukuemeka R. Blyden, "Edward Wilmot Blyden and Africanism in America", A Virtual Museum of the Life and Work of Edward Wilmot Blyden (1832–1912), 1995, Columbia University; accessed 3 January 2011.

- ↑ George Bornstein, "The Colors of Zion: Black, Jewish, and Irish Nationalisms at the turn of the Century", Modernism/modernity 12.3 (2005), Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 369–84.