Electroplating

Electroplating is a process that uses electric current to reduce dissolved metal cations so that they form a thin coherent metal coating on an electrode. The term is also used for electrical oxidation of anions onto a solid substrate, as in the formation silver chloride on silver wire to make silver/silver-chloride electrodes. Electroplating is primarily used to change the surface properties of an object (e.g. abrasion and wear resistance, corrosion protection, lubricity, aesthetic qualities, etc.), but may also be used to build up thickness on undersized parts or to form objects by electroforming.

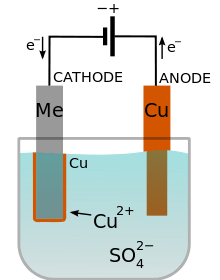

The process used in electroplating is called electrodeposition. It is analogous to a galvanic cell acting in reverse. The part to be plated is the cathode of the circuit. In one technique, the anode is made of the metal to be plated on the part. Both components are immersed in a solution called an electrolyte containing one or more dissolved metal salts as well as other ions that permit the flow of electricity. A power supply supplies a direct current to the anode, oxidizing the metal atoms that it comprises and allowing them to dissolve in the solution. At the cathode, the dissolved metal ions in the electrolyte solution are reduced at the interface between the solution and the cathode, such that they "plate out" onto the cathode. The rate at which the anode is dissolved is equal to the rate at which the cathode is plated, vis-a-vis the current through the circuit. In this manner, the ions in the electrolyte bath are continuously replenished by the anode.[1]

Other electroplating processes may use a non-consumable anode such as lead or carbon. In these techniques, ions of the metal to be plated must be periodically replenished in the bath as they are drawn out of the solution.[2] The most common form of electroplating is used for creating coins such as pennies, which are small zinc plates covered in a layer of copper.[3]

Process

The cations associate with the anions in the solution. These cations are reduced at the cathode to deposit in the metallic, zero valence state. For example, for copper plating, in an acid solution, copper is oxidized at the anode to Cu2+ by losing two electrons. The Cu2+ associates with the anion SO42− in the solution to form copper sulfate. At the cathode, the Cu2+ is reduced to metallic copper by gaining two electrons. The result is the effective transfer of copper from the anode source to a plate covering the cathode.

The plating is most commonly a single metallic element, not an alloy. However, some alloys can be electrodeposited, notably brass and solder.

Many plating baths include cyanides of other metals (e.g., potassium cyanide) in addition to cyanides of the metal to be deposited. These free cyanides facilitate anode corrosion, help to maintain a constant metal ion level and contribute to conductivity. Additionally, non-metal chemicals such as carbonates and phosphates may be added to increase conductivity.

When plating is not desired on certain areas of the substrate, stop-offs are applied to prevent the bath from coming in contact with the substrate. Typical stop-offs include tape, foil, lacquers, and waxes.[4]

The ability of a plating to cover uniformly is called throwing power; the better the "throwing power" the more uniform the coating.[5]

Strike

Initially, a special plating deposit called a "strike" or "flash" may be used to form a very thin (typically less than 0.1 micrometer thick) plating with high quality and good adherence to the substrate. This serves as a foundation for subsequent plating processes. A strike uses a high current density and a bath with a low ion concentration. The process is slow, so more efficient plating processes are used once the desired strike thickness is obtained.

The striking method is also used in combination with the plating of different metals. If it is desirable to plate one type of deposit onto a metal to improve corrosion resistance but this metal has inherently poor adhesion to the substrate, a strike can be first deposited that is compatible with both. One example of this situation is the poor adhesion of electrolytic nickel on zinc alloys, in which case a copper strike is used, which has good adherence to both.[2]

Electrochemical deposition

Electrochemical deposition is generally used for the growth of metals and conducting metal oxides because of the following advantages: (i) the thickness and morphology of the nanostructure can be precisely controlled by adjusting the electrochemical parameters, (ii) relatively uniform and compact deposits can be synthesized in template-based structures, (iii) higher deposition rates are obtained, and (iv) the equipment is inexpensive due to the non-requirements of either a high vacuum or a high reaction temperature.[6][7][8]

Pulse electroplating or pulse electrodeposition (PED)

A simple modification in the electroplating process is the pulse electroplating. This process involves the swift alternating of the potential or current between two different values resulting in a series of pulses of equal amplitude, duration and polarity, separated by zero current. By changing the pulse amplitude and width, it is possible to change the deposited film's composition and thickness.[9]

Brush electroplating

A closely related process is brush electroplating, in which localized areas or entire items are plated using a brush saturated with plating solution. The brush, typically a stainless steel body wrapped with a cloth material that both holds the plating solution and prevents direct contact with the item being plated, is connected to the positive side of a low voltage direct-current power source, and the item to be plated connected to the negative. The operator dips the brush in plating solution then applies it to the item, moving the brush continually to get an even distribution of the plating material. Brush electroplating has several advantages over tank plating, including portability, ability to plate items that for some reason cannot be tank plated (one application was the plating of portions of very large decorative support columns in a building restoration), low or no masking requirements, and comparatively low plating solution volume requirements. Disadvantages compared to tank plating can include greater operator involvement (tank plating can frequently be done with minimal attention), and inability to achieve as great a plate thickness.

Electroless deposition

Usually an electrolytic cell (consisting of two electrodes, electrolyte, and external source of current) is used for electrodeposition. In contrast, an electroless deposition process uses only one electrode and no external source of electric current. However, the solution for the electroless process needs to contain a reducing agent so that the electrode reaction has the form:

In principle any hydrogen-based reducer can be used although the redox potential of the reducer half-cell must be high enough to overcome the energy barriers inherent in liquid chemistry. Electroless nickel plating uses hypophosphite as the reducer while plating of other metals like silver, gold and copper typically use low molecular weight aldehydes.

A major benefit of this approach over electroplating is that the power sources and plating baths are not needed, reducing the cost of production. The technique can also plate diverse shapes and types of surface. The downside is that the plating process is usually slower and cannot create such thick plates of metal. As a consequence of these characteristics, electroless deposition is quite common in the decorative arts.

Cleanliness

Cleanliness is essential to successful electroplating, since molecular layers of oil can prevent adhesion of the coating. ASTM B322 is a standard guide for cleaning metals prior to electroplating. Cleaning processes include solvent cleaning, hot alkaline detergent cleaning, electro-cleaning, and acid treatment etc. The most common industrial test for cleanliness is the waterbreak test, in which the surface is thoroughly rinsed and held vertical. Hydrophobic contaminants such as oils cause the water to bead and break up, allowing the water to drain rapidly. Perfectly clean metal surfaces are hydrophilic and will retain an unbroken sheet of water that does not bead up or drain off. ASTM F22 describes a version of this test. This test does not detect hydrophilic contaminants, but the electroplating process can displace these easily since the solutions are water-based. Surfactants such as soap reduce the sensitivity of the test and must be thoroughly rinsed off.

Effects

Electroplating changes the chemical, physical, and mechanical properties of the workpiece. An example of a chemical change is when nickel plating improves corrosion resistance. An example of a physical change is a change in the outward appearance. An example of a mechanical change is a change in tensile strength or surface hardness which is a required attribute in tooling industry.[10] Electroplating of acid gold on underlying copper/nickel-plated circuits reduces contact resistance as well as surface hardness. Copper-plated areas of mild steel act as a mask if case hardening of such areas are not desired. Tin-plated steel is chromium-plated to prevent dulling of the surface due to oxidation of tin.

History

Modern electrochemistry was invented by Italian chemist Luigi Valentino Brugnatelli in 1805. Brugnatelli used his colleague Alessandro Volta's invention of five years earlier, the voltaic pile, to facilitate the first electrodeposition. Brugnatelli's inventions were suppressed by the French Academy of Sciences and did not become used in general industry for the following thirty years. By 1839, scientists in Britain and Russia had independently devised metal deposition processes similar to Brugnatelli's for the copper electroplating of printing press plates.

Boris Jacobi in Russia not only rediscovered galvanoplastics, but developed electrotyping and galvanoplastic sculpture. Galvanoplastics quickly came into fashion in Russia, with such people as inventor Peter Bagration, scientist Heinrich Lenz and science fiction author Vladimir Odoyevsky all contributing to further development of the technology. Among the most notorious cases of electroplating usage in mid-19th century Russia were gigantic galvanoplastic sculptures of St. Isaac's Cathedral in Saint Petersburg and gold-electroplated dome of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, the tallest Orthodox church in the world.[11]

Soon after, John Wright of Birmingham, England discovered that potassium cyanide was a suitable electrolyte for gold and silver electroplating. Wright's associates, George Elkington and Henry Elkington were awarded the first patents for electroplating in 1840. These two then founded the electroplating industry in Birmingham from where it spread around the world. The Woolrich Electrical Generator of 1844, now in Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum, is the earliest electrical generator used in an industrial process.[12] It was used by Elkingtons.[13][14][15]

The Norddeutsche Affinerie in Hamburg was the first modern electroplating plant starting its production in 1876.[16]

As the science of electrochemistry grew, its relationship to the electroplating process became understood and other types of non-decorative metal electroplating processes were developed. Commercial electroplating of nickel, brass, tin, and zinc were developed by the 1850s. Electroplating baths and equipment based on the patents of the Elkingtons were scaled up to accommodate the plating of numerous large scale objects and for specific manufacturing and engineering applications.

The plating industry received a big boost with the advent of the development of electric generators in the late 19th century. With the higher currents available, metal machine components, hardware, and automotive parts requiring corrosion protection and enhanced wear properties, along with better appearance, could be processed in bulk.

The two World Wars and the growing aviation industry gave impetus to further developments and refinements including such processes as hard chromium plating, bronze alloy plating, sulfamate nickel plating, along with numerous other plating processes. Plating equipment evolved from manually operated tar-lined wooden tanks to automated equipment, capable of processing thousands of kilograms per hour of parts.

One of the American physicist Richard Feynman's first projects was to develop technology for electroplating metal onto plastic. Feynman developed the original idea of his friend into a successful invention, allowing his employer (and friend) to keep commercial promises he had made but could not have fulfilled otherwise.[17]

Uses

Electroplating is widely used in various industries for coating metal objects with a thin layer of a different metal. The layer of metal deposited has some desired property, which the metal of the object lacks. For example, chromium plating is done on many objects such as car parts, bath taps, kitchen gas burners, wheel rims and many others for the fact that chromium is very corrosion resistant, and thus prolongs the life of the parts. Electroplating has wide usage in industries. It is also used in making inexpensive jewelry. Electroplating increases life of metal and prevents corrosion.

Hull cell

The Hull cell is a type of test cell used to qualitatively check the condition of an electroplating bath. It allows for optimization for current density range, optimization of additive concentration, recognition of impurity effects and indication of macro-throwing power capability.[18] The Hull cell replicates the plating bath on a lab scale. It is filled with a sample of the plating solution, an appropriate anode which is connected to a rectifier. The "work" is replaced with a hull cell test panel that will be plated to show the "health" of the bath.

The Hull cell is a trapezoidal container that holds 267 ml of solution. This shape allows one to place the test panel on an angle to the anode. As a result, the deposit is plated at different current densities which can be measured with a hull cell ruler. The solution volume allows for a quantitative optimization of additive concentration: 1 gram addition to 267 mL is equivalent to 0.5 oz/gal in the plating tank.[19]

Haring-Blum Cell

The Haring-Blum Cell is used to determine the macro throwing power of a plating bath. The cell consists of 2 parallel cathodes with a fixed anode in the middle. The cathodes are at distances from the anode in the ratio of 1:5. The macro throwing power is calculating from the thickness of plating at the two cathodes when a dc current is passed for a specific period of time. The cell is fabricated out of Perspex or glass.[20][21]

See also

References

- ↑ Dufour & 2006 IX-1.

- 1 2 Dufour & 2006 IX-2

- ↑ "US Mint Virtual Tour". US Mint.

- ↑ Dufour 2006, p. IX-3

- ↑ "Pollution Prevention Technology Profile Trivalent Chromium Replacements for Hexavalent Chromium Plating". Northeast Waste Management Officials’ Association. 2003-10-18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-06.

- ↑ Coyle, R.T. ; Switzer, J.A. (1989) "Electrochemical synthesis of ceramic films and powders". U.S. Patent 4,882,014

- ↑ Gal-Or, L.; Silberman, I.; Chaim, R. (1991). "Electrolytic ZrO2 Coatings: I. Electrochemical Aspects". J. Electrochem. Soc. 138 (7): 1939. doi:10.1149/1.2085904.

- ↑ Ju, Hyungkuk; Lee, Jae Kwang; Lee, Jongmin; Lee, Jaeyoung (2012). "Fast and selective Cu2O nanorod growth into anodic alumina templates via electrodeposition". Current Applied Physics. 12: 60. doi:10.1016/j.cap.2011.04.042.

- ↑ Chandrasekar, M. S.; Malathy Pushpavanam (2008). "Pulse and pulse reverse plating—Conceptual, advantages and applications". Electrochimica Acta. 53 (8): 3313–3322. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2007.11.054.

- ↑ Todd, Robert H.; Dell K. Allen; Leo Alting (1994). "Surface Coating". Manufacturing Processes Reference Guide. Industrial Press Inc. pp. 454–458. ISBN 0-8311-3049-0.

- ↑ The history of galvanotechnology in Russia (Russian)

- ↑ Birmingham Museums trust catalogue, accession number: 1889S00044

- ↑ Thomas, John Meurig (1991). Michael Faraday and the Royal Institution: The Genius of Man and Place. Bristol: Hilger. p. 51. ISBN 0750301457.

- ↑ Beauchamp, K G (1997). Exhibiting Electricity. IET. p. 90. ISBN 9780852968956.

- ↑ Hunt, L. B. (March 1973). "The early history of gold plating". Gold Bulletin. 6 (1): 16–27. doi:10.1007/BF03215178.

- ↑ Stelter, M.; Bombach, H. (2004). "Process Optimization in Copper Electrorefining". Advanced Engineering Materials. 6 (7): 558. doi:10.1002/adem.200400403.

- ↑ Richard Feynman, Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! (1985), in chap. 6: ["The Chief Research Chemist of the Metaplast Corporation"]

- ↑ Metal Finishing: Guidebook and Directory. Issue 98. 95. 1998. p. 588.

- ↑ Kushner, Arthur S. (December 1, 2006) Hull Cell 101. Products Finishing

- ↑ Bard, Allan; Inzelt, Gyorgy; Scholz, Fritz, eds. (2012). "Haring-Blum Cell". Electrochemical Dictionary. Springer. p. 444. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-29551-5_8. ISBN 978-3-642-29551-5.

- ↑ Wendt, Hartmut; Kreyse, Gerhard (1999). Electrochemical Engineering: Science and Technology in Chemical and Other Industries. Springer. p. 122. ISBN 3540643869.

Bibliography

- Dufour, Jim (2006). An Introduction to Metallurgy, 5th edition. Cameron.

.jpg)