Eliza Haywood

Eliza Haywood (c. 1693 – 25 February 1756), born Elizabeth Fowler, was an English writer, actress and publisher. An increase in interest and recognition of Haywood’s literary works began in the 1980s. Described as "prolific even by the standards of a prolific age", Haywood wrote and published over seventy works during her lifetime including fiction, drama, translations, poetry, conduct literature and periodicals.[1] Haywood is a significant figure of the 18th century as one of the important founders of the novel in English. Today she is studied primarily as a novelist.

Biography

Scholars of Eliza Haywood universally agree upon only one thing: the exact date of her death.[2] Haywood gave conflicting accounts of her own life; her origins remain unclear, and there are presently contending versions of her biography.[3] For example, it was once mistakenly believed that she married the Rev. Valentine Haywood.[4] According to report, Haywood took pains to keep her personal life private, asking the one (unnamed) person with knowledge of her private life to remain silent for fear that such facts may be misrepresented in print. Apparently, that person felt loyal enough to Haywood to honor her request.[5]

The early life of Eliza Haywood is somewhat of a mystery to scholars. While Haywood was born "Eliza Fowler," the exact date of Haywood's birth is unknown due to the lack of surviving records. Although, scholars believe that she was most likely born near Shropshire or London, England in 1693. This birth date is extrapolated from a combination of her death date and her stated age at the time of her death (as Haywood died on February 25, 1756 and obituaries notices list her age as sixty years old).

Haywood’s familial connections, education status, and social position are unknown. Some scholars have speculated that she is related to Sir Richard Fowler of Harnage Grange, who had a younger sister named Elizabeth.[5] Others have stated that Haywood was most likely from London, England as several Elizabeths were born to Fowler families in 1693 in London, however, no evidence exists to positively solidify either of these possible connections.[5] Her first entry in public records appears in Dublin, Ireland, in 1715. In this entry, she is listed as "Mrs. Haywood," performing in Thomas Shadwell's Shakespeare adaptation, Timon of Athens; or, The Man-Hater at the Smock Alley Theatre.[6] Haywood’s marital status is self-identified as “widow,” noting that her marriage was “unfortunate” in 1719. While Haywood was listed as "Mrs." Haywood in public records and she references her unfortunate marriage once in a letter, no record of her marriage have been found and the identity of her husband remains unknown.

Scholars have speculated that Haywood had an affair and even a child with Richard Savage in the 1720s, as well as an open twenty-year live-in relationship with William Hatchett, who was suspected of being the father of her second child.[7] However, later critics have called these speculations into question as too heavily influenced by Alexander Pope's famous illustration of her in The Dunciad and too little based upon hard facts (Pope depicted Haywood as a grotesque figure with two "babes of love" at her side, one by a poet and the other by a bookseller). Other accounts from the period, however, suggest that her "friends" rejected Pope's scandalous depiction of her; they maintained that she had been deserted by her husband and left to raise their children alone. In fact, and despite the popular belief that she was once a woman of ill repute, Haywood seems to have had no particular scandals attached her name whatsoever.[5]

Haywood's friendship with Richard Savage is thought to have begun around 1719, just after the anonymous publication of Part I of her first novel, Love in Excess. Savage wrote the gushing 'puff' for Part I of the novel. The two appear to have been close in these early years, sharing many associates in literary and theatrical circles, even sharing the same publisher, William Chetwood. By September 1725, however, Savage and Haywood had fallen out, and his anonymous attack on her as a 'cast-off Dame' desperate for acclaim in The Authors of the Town struck a chord. Savage is considered the likely impetus for Pope's attack on Haywood, as well.[5]

Haywood's association with Aaron Hill and the literary coterie known as The Hillarians seems to have followed a similar pattern as Haywood rose to fame. The Hillarians were a collection of writers and artists "committed to a progressive programme of ameliorating 'politeness'," and included Savage, Hill, Martha Sansom, and for a time, Haywood. The group shared poems to and about each other, and formed a social circle of like minds. Haywood seems to have greatly admired Hill - who, though not a patron, seems to have promoted young and upcoming artists - and dedicated poems to him. She may have even seen him as a mentor during the earliest years of her career.[5]

William Hatchett was a long-time colleague and collaborator. The two probably met around 1728 or 1729, and recent critics have touted the pair as domestic partners or lovers, though this suggestion has now been challenged. He was a player, playwright, pamphleteer, and translator (and perhaps "sponge") who shared a stage career with Haywood, and they collaborated on an adaptation of The Tragedy of Tragedies by Henry Fielding (with whom she also collaborated) and an opera, The Opera of Operas; or, Tom Thumb the Great (1733).[7] Hatchett has even been considered the father of Haywood's second child (based on Pope's reference to "a Bookseller" as a father of one of her children, though Hatchett was not a bookseller). No clear evidence supporting this or a domestic partnership is extant.[5]

Haywood’s writing career began in 1719 with the first installment of Love in Excess, a novel, and ended in the year she died with conduct books The Wife and The Husband, and the biweekly periodical The Young Lady. She wrote in almost every genre, and many of her works were published anonymously. Haywood is now considered "the foremost female 'author by profession' and businesswoman of the first half of the eighteenth century," tireless and prolific in her endeavors as an author, poet, playwright, periodical writer and editor, and publisher. During the early 1720s, "Mrs Haywood" dominated the novel market in London, so much so that contemporary Henry Fielding created a comic character, "Mrs Novel" in the Author's Farce, modeled after her.[5]

She fell ill in October 1755 and died on 25 February 1756, actively publishing up until her death. She was buried in Saint Margaret's Church near Westminster Abbey in Westminster in an unmarked grave in the churchyard. For unknown reasons, her burial was delayed by about a week and her death duties remain unpaid.

Acting and drama

Haywood began her acting career in 1715 at the Smock Alley Theatre in Dublin. Public records for this year list her as "Mrs. Haywood," appearing in Thomas Shadwell's Shakespeare adaptation, Timon of Athens; or, The Man-Hater.[3] By 1717, she had moved to Lincoln's Inn Fields, where she worked for John Rich. Rich had her rewrite a play called The Fair Captive. The play only ran for three nights (to the author's benefit), but Rich added a fourth night as a benefit for the second author, Haywood. In 1723, her first play, A Wife to be Lett, was staged.

During the second half of the 1720s, Haywood continued acting, and she moved over to the Haymarket Theatre to join with Henry Fielding in the opposition plays of the 1730s. In 1729, she wrote Frederick, Duke of Brunswick-Lunenburgh to honour the future George II of the United Kingdom. George II, as Prince of Wales, was a locus for Tory opposition to the ministry of Robert Walpole. As he had made it clear that he did not favour his father's policies or ministry, praise for him was demurral from the present king. Others, such as James Thomson and Henry Brooke, were also writing such "patriotic" (which is to say in support of the Patriot Whigs) plays at the time, and Henry Carey was soon to satirise the failed promise of George II.

Haywood's greatest success at Haymarket came with The Opera of Operas, an operatic adaptation of Fielding's Tragedy of Tragedies (with music by J. F. Lampe and Thomas Arne) in 1733. However, it was an adaptation with a distinct difference. Caroline of Ansbach had affected a reconciliation between George I and George II, and this meant an endorsement by George II of the Whig ministry. Haywood's adaptation contains a reconciliation scene, replete with symbols from Caroline's own grotto. This was an enunciation of a change by Haywood herself away from any Tory, or anti-Walpolean, causes that she had supported previously, and it did not go unnoticed by her contemporaries.

In 1735, she wrote a one-volume Companion to the Theatre. This book contains plot summaries of contemporary plays, literary criticism, and dramaturgical observations. In 1747 she added a second volume.

After the Licensing Act of 1737, the playhouse was shut against adventurous new plays.

Fiction

Haywood, Delarivier Manley and Aphra Behn were known as "The fair triumvirate of wit" and are considered the most prominent writers of amatory fiction. Eliza Haywood’s prolific fiction develops from titillating romance novels and amatory fiction during the early 1720s to works focused more on "women's rights and position" (Schofield, Haywood 63) in the later 1720s into the 1730s. In the middle novels of her career, women were locked up, tormented and beleaguered by domineering men. In the later novels of the 1740s and 1750s however, marriage was viewed as a positive situation between men and women.

Due to the economy of publishing in the 18th century, her novels often ran to multiple volumes. Authors were paid only once for a book and received no royalties; a second volume meant a second payment.

Haywood’s first novel, Love in Excess; Or, The Fatal Enquiry (1719–1720) touches on themes of education and marriage. Often classified as a work of amatory fiction, this novel is notable for its treatment of the fallen woman. D’Elmonte, the novel's male protagonist, reassures one woman that she should not condemn herself: “There are times, madam”, he says “in which the wisest have not power over their own actions.” The fallen woman is given an unusually positive portrait.

Idalia; or The Unfortunate Mistress (1723) is divided into three parts. In the first, Idalia is presented as a young motherless, spoiled, and wonderful Venetian aristocrat whose varied amorous adventures are to carry her over most of Italy. Already in Venice she is sought by countless suitors, among them the base Florez, whom her father forbids the house. One suitor, who is Florez’s friend, Don Ferdinand, resigns his suit, but Idalia’s vanity is piqued at the loss of an even a single adorer, and more from perverseness than from love she continues to correspond with him. She meets him, and he eventually effects her ruin. His beloved friend, Henriquez conducts her to Padua, but becomes the victim of her charms; he quarrels with Ferdinand, and they eventually kill each other in a duel.

In the second part, Henriquez’ brother, Myrtano, succeeds as Idalia’s principal adorer, and she reciprocates his love. She then receives a letter informing her about Myrtano’s engagement to another woman, so she leaves for Verona, hoping to enter a convent. On the road her guide takes her to a rural retreat with the intention of killing her, but she escapes to Ancona from where she takes ship for Naples. The sea captain pays her crude court, but just in time to save her from his embraces the ship is captured by corsairs commanded by a young married couple. Though the heroine is in peasant dress, she is treated with distinction by her captors. Her history moves them to tears and they in turn are in the midst of relating to Idalia the involved story of their courtship when the vessel is wrecked in a gale.

In the third part, we find Idalia borne ashore on a plank; succoured by cottagers she continues her journey towards Rome in a man’s clothes. On the way robbers beat her and leave her for dead. She is found and taken home by a lady, Antonia, who falls in love with her. Idalia later discovers that Antonia’s husband is her dear Myrtano. Their happiness is interrupted by the jealousy of his wife, who first tries to poison everyone and after appeals to the Pope to separate them. Idalia is taken to Rome first in a convent where she leads a miserable life, persecuted by all the young gallants of the city. Then one day she sees Florez, the first cause of her misfortunes. With thoughts of revenge, she sends him a billet, but Myrtano, keeps the appointment instead of Florez. Not recognizing her lover, muffled in a cloak, Idalia stabs him, but upon recognizing him is overcome by remorse, and dies by the same knife.

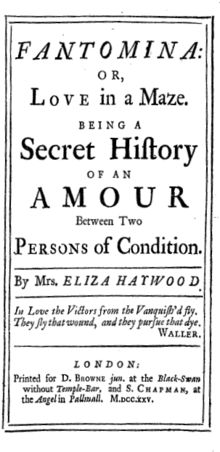

Fantomina; or Love in a Maze (1724) is a short story about a woman who assumes the roles of a prostitute, a maid, a widow, and a Lady to repeatedly seduce a man named Beauplaisir. Schofield points out that, "Not only does she satisfy her own sexual inclinations, she smugly believes that 'while he thinks to fool me, [he] is himself the only beguiled Person'” (50). This novel asserts that women have some access to power in the social sphere, one of the recurring themes in Haywood’s work. It has been argued that it is indebted to the interpolated tale of the "Invisible Mistress" in Paul Scarron's Roman Comique.[8]

The Mercenary Lover; or, The Unfortunate Heiresses (1726) is a novella examining the risks women face in giving way to passion. Miranda, the eldest of two heiress sisters, marries Clitander, the mercenary lover of the title. Unsatisfied with Miranda's half of the estate, Clitander seduces Althea, the younger sister, by plying her with romantic books and notions. She gives way to "ungovernable passion" and becomes pregnant. Clitander fools her into signing over her inheritance, then poisons her, killing both her and the unborn child.

The Distress'd Orphan; or Love in a Madhouse (1726) is a novella that relates the plight of a woman falsely imprisoned in a private madhouse. In Patrick Spedding's A Bibliography of Eliza Haywood, he notes that The Distress'd Orphan; or Love in a Madhouse was more "enduringly popular," "reprinted more often, in larger editions, and remained in print for a longer period, than ... Love in Excess" (21).[9] The story recounts the story of Annilia, who is an orphan and heiress. Her uncle and guardian, Giraldo, plans to gain access to her fortune by having her marry his son, Horatio. When Annilia meets Colonel Marathon at a dance and they fall in love, she rejects her uncle's plan and prepares to move out of his home. In response, Giraldo declares she is insane and has her imprisoned in a private madhouse, thus gaining control of her inheritance. Annilia languishes in the madhouse until Marathon enters it as a supposed patient and rescues her.

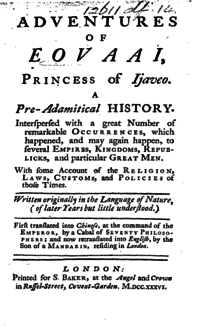

The Adventures of Eovaii: A Pre-Adamitical History (1736) was also titled The Unfortunate Princess (1741). It is a satire of Prime Minister Robert Walpole, told through a sort of oriental fairy tale.

The Anti-Pamela; or Feign’d Innocence Detected (1741) is a satirical response to Samuel Richardson’s didactic novel Pamela, or, Virtue Rewarded (1740). It makes fun of the idea of bargaining one’s maidenhead for a place in society. Contemporary writer Henry Fielding also responded to Pamela with An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews (1741).

The Fortunate Foundlings (1744) is a picaresque novel in which two children of opposite sex experience the world differently, according to their gender.

The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless (1751) is a sophisticated, multi-plot novel that has been deemed the first novel of female development in English. Betsy leaves her emotionally and financially abusive husband Munden and experiences independence for a time before she decides to marry again. Written a few years before her marriage conduct books were published, the novel contains advice on marriage in the form of quips from Lady Trusty. Her "patriarchal conduct-book advice to Betsy is often read literally as Haywood's new advice for her female audience. However, Haywood's audience consisted of both men and women, and Lady Trusty's bridal admonitions, the most conservative and patriarchal words of advice in the novel, are contradictory and impossible for any woman to execute completely" (Stuart).

Betsy Thoughtless represents an important change in the 18th century novel. It portrays a mistaken but intelligent and strong-willed woman who gives way to society’s pressures toward marriage. According to Backsheider, Betsy Thoughtless is a novel of marriage, rather than the more popular novel of courtship and thus foreshadows the type of domestic novel that would culminate in the 19th century such as Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Instead of concerning itself with attracting a partner well, Betsy Thoughtless is concerned with marrying well, and its heroine learns that giving way to the role of women in marriage can be fulfilling.

The most detailed and up-to-date bibliography available is Patrick Spedding, A Bibliography of Eliza Haywood. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2004.

Periodicals and Non-fiction

While she was writing popular novels, Eliza Haywood was also working on periodicals, essays and manuals on social behaviour (conduct books). The Female Spectator (4 volumes, 1744–46), a monthly periodical, was written in answer to the contemporary journal The Spectator by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele. In The Female Spectator, Haywood wrote in four personas (Mira, Euphrosine, Widow of Quality and The Female Spectator) and took positions on public issues such as marriage, children, reading, education and conduct. It was the first periodical written for women by a woman and arguably one of Haywood’s most significant contributions to women's writing. Haywood followed a lead by contemporary John Dunton who issued the Ladies' Mercury as a companion to his successful Athenian Mercury. Even though The Ladies' Mercury was a self-proclaimed women’s journal, it was produced by men (Spacks xii).

The Parrot (1746) apparently earned her questions from the government for political statements about Charles Edward Stuart.

Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots (1725) is termed a "hybrid" work by Schofield (103); being a work of non-fiction but making use of narrative techniques. Reflections on the Various Effects of Love (1726) is a didactic account of what can happen to a woman when she gives in to her passions. This piece demonstrates the sexual double standard that allow men to love freely without social consequence and women to be scandalised for doing the same.

The Wife and The Husband (1756) are conduct books for each partner in a marriage. The Wife was first published anonymously (by Mira, one of Haywood's personas from The Female Spectator); The Husband: in Answer to The Wife followed later the same year with Haywood’s name attached.

Haywood also worked on sensational pamphlets on the famous contemporary deaf-mute prophet, Duncan Campbell. These include A Spy Upon the Conjurer (1724) and The Dumb Projector: Being a Surprising Account of a Trip to Holland Made by Duncan Campbell (1725).

Political writings

.png)

.png)

Eliza Haywood was active in politics during her entire career, although she had a party change around the time of the reconciliation of George II with Robert Walpole. She wrote a series of parallel histories, beginning with 1724's Memoirs of a Certain Island, Adjacent to Utopia, and then The Secret History of the Present Intrigues of the Court of Caramania in 1727. She published Memoirs of an Unfortunate Young Nobleman in 1743. In 1746 she started another journal, The Parrot, which got her questioned by the government for political statements about Charles Edward Stuart, as she was writing just after the Jacobite rising of 1745. This would happen again with the publication of A Letter from H---- G----g, Esq. in 1750. She grew more directly political with The Invisible Spy in 1755 and The Wife in 1756.

Translations

Haywood published eight translations of popular continental romances. They include: Letters from a Lady of Quality (1721) (translation of Edme Boursault's play); The Lady’s Philosopher's Stone (1723) (translation of Louis Adrien Duperron de Castera’s historical novel); La Belle Assemblée (1724–34) (translation of Madame de Gomez’s novella); Love in its Variety (1727) (translation of Matteo Bandello’s stories); The Disguis'd Prince (1728) (translation of Madame de Villedieu’s 1679 novel); The Virtuous Villager (1742) (translation of Charles de Fieux's work); and (with William Hatchett) The Sopha (1743) (translation of Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon's novel).

Critical reception

Haywood is notable as a transgressive, outspoken writer of amatory fiction, plays, romance and novels. Paula R. Backscheider claims that "Haywood's place in literary history is equally remarkable and as neglected, misunderstood, and misrepresented as her oeuvre" (xiii intro drama). For quite some time Eliza Haywood was most frequently noted for her appearance in Alexander Pope's The Dunciad rather than for her own literary merits. Even though Alexander Pope made her a centerpoint in the heroic games of The Dunciad in Book II—she is, in Pope's view, "vacuous"–he does not dismiss her for being a woman, but for having nothing of her own to say. Pope attacks her for politics and for, implicitly, plagiarism. Unlike other "dunces", however, Pope's characterisation does not seem to have been the cause of her obscurity. Rather, as literary historians came to praise and value the masculine novel and, most importantly, to dismiss the courtship novel and to exclude novels of eroticism, Haywood's works were rejected for more chaste or more overtly philosophical works.

In The Dunciad, the book sellers race each other to reach Eliza, and their reward will be all of her books and her company. She is for sale, in other words, in literature and society, in Pope's view. As with other "dunces", she was not without complicity in the attack. Haywood had begun to make it known that she was poor and in need of funds, and she seemed to be writing for pay and to please the undiscerning public.

Eliza Haywood is now regarded as "a case study in the politics of literary history" (Backscheider 100). She is also being re-evaluated by feminist scholars and rated very highly. Interest in Haywood’s work has been growing since the 1980s. Her novels are regarded as stylistically innovative. Her plays and political writing attracted most of the attention in her own time, and she was a full player in the difficult public sphere.

Her novels, voluminous and frequent, are now regarded as stylistically innovative and important transitions from the erotic seduction novels and poetry of Aphra Behn (particularly Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister (1684)) and the straightforward, plainly spoken novel of Frances Burney. In her own day, her plays and political writing attracted the most comment and attention, and thus she was a full player in the difficult public sphere, but today her novels carry the most interest and demonstrate the most significant innovation.

Haywood as a Publisher

Works Published Under Her Imprint:

Haywood not only wrote works to be published, she also participated in the publication process. Haywood published, sometimes in collaboration with William Hatchett, at least nine works under her own imprint. Most of these were available for sale at the Sign of Fame (her pamphlet shop located in Covent Gardens), including:

- Anti-Pamela by Eliza Haywood (1741)

- Sublime Character of his Excellency Somebody by Unknown (1741)-

- Title page states that the work was “Originally Written by a Celebrated French Wit”

- The Busy-Body: or, Successful Spy by Susannah Centlivre (1742)

- The Ghost of Eustace Budgel Esq. to the Man in Blue possibly by William Hatchett (1742)

- The Right Honourable, sir Robert Walpole, (Now Earl of Orford) Vindicated by “A Brother Minister in Disgrace” (1742)

- The Virtuous Villager by Eliza Haywood (1742)

- A Remarkable Cause on a Note of Hand by William Hatchett (1742)

- The Equity of Parnassus by Unknown (1744)

- A Letter from H[enry] G[orin]g by Eliza Haywood (1749)

King notes that the eighteenth-century definition for “publisher” could also mean “bookseller.” King is uncertain whether Haywood produced the books and pamphlets that she sold (as Spedding indicates) or if she was a bookseller, especially for Haywood’s early productions.[5] Haywood sometimes collaborated on publishing matters in order to share the costs, as she did when she collaborated with Cogan on the publication of The Virtuous Villager.[5] In any case, Haywood was most certainly a bookseller due to the fact that there were a great number and variety of works “to be had” at the Sign of Fame that did not bare her imprint.[5]

Works by Haywood

Collections Written by Eliza Haywood and Published before 1850:

- The Danger of Giving Way to Passion (1720-1723)

- The Works (3 volumes, 1724)

- Secret Histories, Novels and Poems (4 volumes, 1725)

- Secret Histories, Novels, Etc. (1727)

Individual Works Written by Eliza Haywood and Published Before 1850:

- Love in Excess (1719-1720)

- Letters from a Lady of Quality (1720) (translation of Edme Boursault's play)

- The Fair Captive (1721)

- The British Recluse (1722)

- The Injur'd Husband (1722)

- Idalia; or The Unfortunate Mistress (1723)

- A Wife to be Lett (1723)

- Lasselia; or The Self-Abandon’d (1723)

- The Rash Resolve; or, The Untimely Discovery (1723)

- Poems on Several Occasions (1724)

- A Spy Upon the Conjurer (1724)

- The Lady’s Philosopher's Stone (1725) (translation of Louis Adrien Duperron de Castera’s historical novel)

- The Masqueraders; or Fatal Curiosity (1724)

- The Fatal Secret; or, Constancy in Distress (1724)

- The Surprise (1724)

- The Arragonian Queen: A Secret History (1724)

- The Force of Nature; or, The Lucky Disappointment (1724)

- Memoirs of the Baron de Brosse (1724)

- La Belle Assemblée (1724-1734) (translation of Madame de Gomez’s novella)

- Fantomina; or Love in a Maze (1725)

- Memoirs of a Certain Island Adjacent to the Kingdom of Utopia (1725)

- Bath Intrigues: in four Letters to a Friend in London (1725)

- The Unequal Conflict (1725)

- The Tea-Table (1725)

- The Dumb Projector: Being a Surprising Account of a Trip to Holland Made by Duncan Campbell (1725)

- The Fatal Fondness (1725)

- Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots (1725)

- The Mercenary Lover; or, the Unfortunate Heiresses (1726)

- Reflections on the Various Effects of Love (1726)

- The Distressed Orphan; or, Love in a Madhouse (1726)

- The City Jilt; or, The Alderman Turn’d Beau (1726)

- The Double Marriage; or, The Fatal Release (1726)

- The Secret History of the Present Intrigues of the Court of Carimania (1726)

- Letters from the Palace of Fame (1727)

- Cleomelia; or The Generous Mistress (1727)

- The Fruitless Enquiry (1727)

- The Life of Madam de Villesache (1727)

- Love in its Variety (1727) (translation of Matteo Bandello’s stories)

- Philadore and Placentia (1727)

- The Perplex’d Dutchess; or Treachery Rewarded (1728)

- The Agreeable Caledonian; or, Memoirs of Signiora di Morella (1728)

- Irish Artifice; or, The History of Clarina (1728)

- The Disguis'd Prince (1728) (translation of Madame de Villedieu’s 1679 novel)

- The City Widow (1728)

- Persecuted Virtue; or, The Cruel Lover (1728)

- The Fair Hebrew; or, A True, but Secret History of Two Jewish Ladies (1729)

- Frederick, Duke of Brunswick-Lunenburgh (1729)

- Love-Letters on All Occasions Lately Passed between Persons of Distinction (1730)

- The Opera of Operas (1733)

- L'Entretien des Beaux Esprits (1734)

- The Dramatic Historiographer (1735)

- Arden of Feversham (1736)

- Adventures of Eovaai, Princess of Ijaveo: A Pre-Adamitical History (1736)

- Alternative title The Unfortunate Princess, or The Ambitious Statesman (2nd edition, 1741)

- The Anti-Pamela; or Feign’d Innocence Detected (1741)

- The Virtuous Villager (1742) (translation of Charles de Fieux's work)

- The Sopha (1743) (translation of Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon's novel)

- Memoirs of an Unfortunate Young Nobleman (1743)

- A Present for a Servant Maid; or, the Sure Means of Gaining Love and Esteem (1743)

- The Fortunate Foundlings (1744)

- The Female Spectator (4 volumes, 1744–1746)

- The Parrot (1746)

- Memoirs of a Man of Honour (1747)

- Life’s Progress through the Passions; or, The Adventures of Natura (1748)

- Epistle for the Ladies (1749)

- Dalinda; or The Double Marriage (1749)

- A Letter from H------ G--------, Esq., One of the Gentlemen of the Bedchamber of the Young Chevalier (1750)

- The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless (1751)

- The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy (1753)

- The Invisible Spy (1754)

- The Wife (1756)

- The Young Lady (1756)

- The Husband (1756)

Also See:

See also

Notes

- ↑ Haywood, Eliza (1985). The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless. Broadview Press Ltd. p. 7.

- ↑ King, Kathryn R. (2012). A Politcal Biography of Eliza Haywood. Pickering & Chatto. pp. xi.

- ↑ Blouch, Christine (Summer 1991). "Eliza Haywood and the Romance of Obscurity". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500-1900. 31 (3): 535–551. doi:10.2307/450861. JSTOR 450861. This author offers a summary of conflicting biographies of Haywood.

- ↑ Whicher, Chapter I, for example. Corrected by Blouch, 539.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 King, Kathryn R. (2012). A Political Biography of Eliza Haywood. London: Pickering & Chatto. pp. xi–xii, 1–15, 17–24, 30–1, 58–65. ISBN 9781851966769.

- ↑ Blouch, 536–538

- 1 2 Bocchicchio, Rebecca P. (2000). Kirsten T. Saxton, ed. The passionate fictions of Eliza Haywood: essays on her life and work. University Press of Kentucky. p. 6. ISBN 0-8131-2161-2.

- ↑ Hinnant, Charles H. (December 2010). "Ironic Inversion in Eliza Haywood's Fiction: Fantomina and 'The History of the Invisible Mistress'". Women's Writing. 17 (3): 403–412. doi:10.1080/09699080903162021.

- ↑ Spedding, Patrick (2004). A Bibliography of Eliza Haywood. London: Pickering & Chatto. p. 21.

References

- Blouch, Christine. "Eliza Haywood and the Romance of Obscurity." Studies in English Literature 1500–1900 no. 31 (1991): 535–551.

- Backscheider, Paula R. "Eliza Haywood." In Matthew, H.C.G. and Brian Harrison, eds. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 26, 97–100. London: OUP, 2004.

- Bowers, Toni. "Sex, Lies, and Invisibility: Amatory Fiction from Behn to Haywood", in The Columbia History of the British Novel John J. Richetti, Ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994: 50–72.

- King, Kathryn R. A Political Biography of Eliza Haywood. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2012. xi–xii, 1–15, 17–24, 30–1, 58–65, 90-98.

- Schofield, Mary Anne. Eliza Haywood. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1985.

- Spacks, Patricia Meyer. Introduction. Selections from The Female Spectator: Eliza Haywood. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ix–xxi.

- Spedding, Patrick. A Bibliography of Eliza Haywood. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2004.

- Stuart, Shea. "Subversive Didacticism in Eliza Haywood's Betsy Thoughtless." Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 42.3 (2002): 559–575.

External links

| Library resources about Eliza Haywood |

| By Eliza Haywood |

|---|

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Eliza Haywood |

- Works by Eliza Haywood at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Eliza Haywood at Internet Archive

- Works by Eliza Haywood at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Eliza Haywood Criticism, Texts and E-texts

- Essays by Eliza Haywood at Quotidiana.org

- Essay on Haywood in the contemporary classroom at 18thCenturyCommon.org

- E-text of The Life and Romances of Mrs. Eliza Haywood / Whicher, George Frisbie, 1915