Ellis wormhole

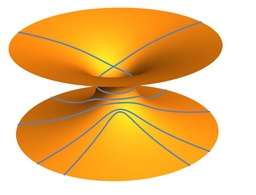

The Ellis wormhole is the special case of the Ellis drainhole in which the 'ether' is not flowing and there is no gravity. What remains is a pure traversable wormhole comprising a pair of identical twin, nonflat, three-dimensional regions joined at a two-sphere, the 'throat' of the wormhole. As seen in the image shown, two-dimensional equatorial cross sections of the wormhole are catenoidal 'collars' that are asymptotically flat far from the throat. There being no gravity in force, an inertial observer (test particle) can sit forever at rest at any point in space, but if set in motion by some disturbance will follow a geodesic of an equatorial cross section at constant speed, as would also a photon. This phenomenon shows that in space-time the curvature of space has nothing to do with gravity (the 'curvature of time’, one could say).

As a special case of the Ellis drainhole, itself a 'traversable wormhole', the Ellis wormhole dates back to the drainhole's discovery in 1969 (date of first submission) by H. G. Ellis,[1] and independently at about the same time by K. A. Bronnikov.[2]

Ellis and Bronnikov derived the original traversable wormhole as a solution of the Einstein vacuum field equations augmented by inclusion of a scalar field minimally coupled to the geometry of space-time with coupling polarity opposite to the orthodox polarity (negative instead of positive). Some years later M. S. Morris and K. S. Thorne manufactured a duplicate of the Ellis wormhole to use as a tool for teaching general relativity,[3] asserting that existence of such a wormhole required the presence of 'negative energy', a viewpoint Ellis had considered and explicitly refused to accept, on the grounds that arguments for it were unpersuasive.[1]

The wormhole solution

The wormhole metric has the proper-time form

where

and is the drainhole parameter that survives after the parameter of the Ellis drainhole solution is set to 0 to stop the ether flow and thereby eliminate gravity. If one goes further and sets to 0, the metric becomes that of Minkowski space-time, the flat space-time of the special theory of relativity.

In Minkowski space-time every timelike and every lightlike (null) geodesic is a straight 'world line' that projects onto a straight-line geodesic of an equatorial cross section of a time slice of constant as, for example, the one on which and , the metric of which is that of euclidean two-space in polar coordinates , namely,

Every test particle or photon is seen to follow such an equatorial geodesic at a fixed coordinate speed, which could be 0, there being no gravitational field built into Minkowski space-time. These properties of Minkowski space-time all have their counterparts in the Ellis wormhole, modified, however, by the fact that the metric and therefore the geodesics of equatorial cross sections of the wormhole are not straight lines, rather are the 'straightest possible' paths in the cross sections. It is of interest, therefore, to see what these equatorial geodesics look like.

Equatorial geodesics of the wormhole

The equatorial cross section of the wormhole defined by and (representative of all such cross sections) bears the metric

When the cross section with this metric is embedded in euclidean three-space the image is the catenoid shown above, with measuring the distance from the central circle at the throat, of radius , along a curve on which is fixed (one such being shown). In cylindrical coordinates the equation has as its graph.

After some integrations and substitutions the equations for a geodesic of parametrized by reduce to

and

where is a constant. If then and and vice versa. Thus every 'circle of latitude' ( constant) is a geodesic. If on the other hand is not identically 0, then its zeroes are isolated and the reduced equations can be combined to yield the orbital equation

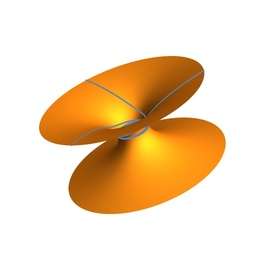

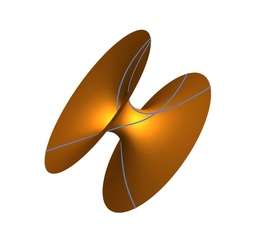

There are three cases to be considered:

- which implies that thus that the geodesic is confined to one side of the wormhole or the other and has a turning point at or

- which entails that so that the geodesic does not cross the throat at but spirals onto it from one side or the other;

- which allows the geodesic to traverse the wormhole from either side to the other.

The figures exhibit examples of the three types. If is allowed to vary from to the number of orbital revolutions possible for each type, latitudes included, is unlimited. For the first and third types the number rises to infinity as for the spiral type and the latitudes the number is already infinite.

That these geodesics can bend around the wormhole makes clear that the curvature of space alone, without the aid of gravity, can cause test particles and photons to follow paths that deviate significantly from straight lines and can create lensing effects.

Dynamic Ellis wormhole

There is a dynamic version of the Ellis wormhole that is a solution of the same field equations that the static Ellis wormhole is a solution of.[4] Its metric is

where

being a positive constant. There is a 'point singularity' at but everywhere else the metric is regular and curvatures are finite. Geodesics that do not encounter the point singularity are complete; those that do can be extended beyond it by proceeding along any of the geodesics that encounter the singularity from the opposite time direction and have compatible tangents (similarly to geodesics of the graph of that encounter the singularity at the origin).

For a fixed nonzero value of the equatorial cross section on which has the metric

This metric describes a 'hypercatenoid' similar to the equatorial catenoid of the static wormhole, with the radius of the throat (where ) now replaced by and in general each circle of latitude of geodesic radius having circumferential radius .

For the metric of the equatorial cross section is

which describes a 'hypercone' with its vertex at the singular point, its latitude circles of geodesic radius having circumferences Unlike the catenoid, neither the hypercatenoid nor the hypercone is fully representable as a surface in euclidean three-space; only the portions where (thus where or equivalently ) can be embedded in that way.

Dynamically, as advances from to the equatorial cross sections shrink from hypercatenoids of infinite radius to hypercones (hypercatenoids of zero radius) at then expand back to hypercatenoids of infinite radius. Examination of the curvature tensor reveals that the full dynamic Ellis wormhole space-time manifold is aymptotically flat in all directions timelike, lightlike, and spacelike.

Applications

- The Ellis wormhole served as the starting point for building the traversable wormhole featured in the 2014 movie Interstellar.[5]

- Scattering by an Ellis wormhole[6]

- Spatial lensing (not gravitational lensing, as there is no gravity) in the Ellis wormhole

References

- 1 2 H. G. Ellis (1973). "Ether flow through a drainhole: A particle model in general relativity". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 14: 104–118. doi:10.1063/1.1666161.

- ↑ K. A. Bronnikov (1973). "Scalar-tensor theory and scalar charge". Acta Physica Polonica. B4: 251–266.

- ↑ M. S. Morris; K. S. Thorne (1988). "Wormholes in spacetime and their use for interstellar travel: A tool for teaching general relativity". American Journal of Physics. 56: 395–412. doi:10.1119/1.15620.

- ↑ H. G. Ellis (1979). "The evolving, flowless drainhole: A nongravitating-particle model in general relativityt theory". General Relativity and Gravitation. 10: 105–123. doi:10.1007/bf00756794.

- ↑ O. James; E. von Tunzelmann; P. Franklin; K. S. Thorne (2015). "Visualizing Interstellar 's Wormhole". American Journal of Physics. 83: 486–499. doi:10.1119/1.4916949.

- ↑ G. Clément (1984). "Scattering of Klein-Gordon and Maxwell waves by an Ellis geometry". International Journal of Theoretical Physics. 23: 335–350. doi:10.1007/bf02114513.

- ↑ F. Abe (2010). "Gravitational microlensing by the Ellis wormhole". The Astrophysical Journal. 725: 787–793. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/725/1/787.

- ↑ C.-M. Yoo; T. Harada; N. Tsukamoto (2013). "Wave effect in gravitational lensing by the Ellis wormhole". Physical Review D. 87: 084045–1–9. doi:10.1103/physrevd.87.084045.

- ↑ Y. Toki; T. Kitamura; H. Asada; F. Abe (2011). "Astrometric image centroid displacements due to gravitational microlensing by the Ellis wormhole". Astrophysical Journal. 740: 121–1–8. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/740/2/121.

- ↑ V. Perlick (2004). "Exact gravitational lens equation in spherically symmetric and static spacetimes". Physical Review D. 69: 064017–1–10. doi:10.1103/physrevd.69.064017.

- ↑ T. K. Dey; S. Sen (2008). "Gravitational lensing by wormholes". Modern Physics Letters A. 23: 953–962. doi:10.1142/s0217732308025498.

- ↑ K. K. Nandi; Y.-Z. Zhang; A. V. Zakharov (2006). "Gravitational lensing by wormholes". Physical Review D. 74: 024020–1–13. doi:10.1103/physrevd.74.024020.