Eric Harrison (RAAF officer)

| Eric Harrison | |

|---|---|

|

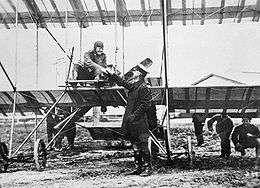

Eric Harrison at Central Flying School, 1914 | |

| Born |

10 August 1886 Castlemaine, Victoria |

| Died |

5 September 1945 (aged 59) Melbourne |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1912–45 |

| Rank | Group Captain |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

Eric Harrison (10 August 1886 – 5 September 1945) was an Australian aviator who made the country's first military flight, and helped lay the groundwork for the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). Born in Victoria, he was a flying instructor in Britain when, in 1912, he answered the Australian Defence Department's call for pilots to form an aviation school. Along with Henry Petre, he established Australia's first air base at Point Cook, Victoria, and its inaugural training unit, the Central Flying School (CFS), before making his historic flight in March 1914. Following the outbreak of World War I, when Petre went on active service with the Mesopotamian Half Flight, Harrison took charge of instructing student pilots of the Australian Flying Corps at CFS.

Harrison transferred to the RAAF as one of its founding members in 1921, and spent much of the inter-war period in technical services and air accident investigation. Promoted to group captain in 1935, he retired from the Air Force three years later when his post of Director of Aeronautical Inspection was transferred to the public service. He continued to serve in the same capacity as a civilian until his sudden death from heart disease at the age of fifty-nine, just after the end of World War II. Harrison's technical abilities and association with military flying from its earliest days in Australia earned him the title of "Father of the RAAF" for many years, until the mantle was assumed by Air Marshal Sir Richard Williams.

Early career

Born on 10 August 1886 at Clinkers Hill near Castlemaine, Victoria, Harrison was the son of printer and stationer Joseph Harrison, and his English-born wife Ann.[1] He attended Castlemaine Grammar School before starting work as a motor mechanic. Keen to fly from the first time he saw an aeroplane, he travelled to Britain in March 1911 and trained as a pilot at the Bristol School on Salisbury Plain. Six months later, having accumulated some thirty minutes' flight time, he qualified for his Royal Aero Club Aviator's Certificate, becoming only the third Australian to do so.[2][3] Gaining employment as an instructor for Bristol, he taught flying on behalf of the company in Spain and Italy, as well as in Halberstadt, Germany, where he became aware first-hand of that country's militarism; some of the students he trained and examined later served as pilots in the Luftstreitkräfte during World War I.[1][4]

In December 1911, the Australian Defence Department advertised in the United Kingdom for "two competent mechanists and aviators" to establish a flying corps and training school. Henry Petre, a former solicitor employed by Handley Page, and H.R. Busteed, then Bristol's chief test pilot, successfully applied.[5][6] Petre was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Australian Military Forces on 6 August 1912, but Busteed withdrew his application in October and Harrison took his place, gaining his commission on 16 December.[1][5] While his new salary of £400 was little improvement on what he was earning in Britain, Harrison was happy to have an excuse to return home.[3]

Petre selected Point Cook, Victoria, to become the site for the Army's proposed Central Flying School (CFS) in March 1913; meanwhile Harrison remained in Britain temporarily, ordering the facility's complement of aircraft including two Deperdussin monoplanes, two Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 biplanes, and a Bristol Boxkite for initial training.[7][8] By January 1914, the pair had established the school with themselves as instructors, augmented by four mechanics and three other staff. Harrison made Australia's first military flight in the Boxkite on Sunday, 1 March 1914, followed by a second in the same aircraft with Petre as passenger, then a third by himself in a Deperdussin.[4][6] On 29 June, Harrison married Kathleen Prendergast, daughter of future Premier of Victoria George Prendergast, at St Mary's Catholic Church in West Melbourne.[1][9]

World War I

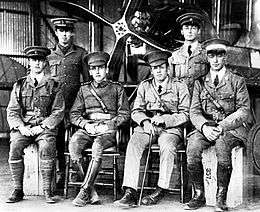

Its coterie of personnel by now being referred to as the Australian Flying Corps (AFC), CFS commenced its first course on 17 August 1914, two weeks after the outbreak of World War I. Its students included Captain Thomas White and Lieutenant Richard Williams, with Harrison providing initial training to solo standard and Petre advanced instruction.[6][10] In September, Harrison was given command of a flying unit that accompanied the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force to Rabaul in German New Guinea. With little in the way of enemy resistance, however, the aircraft were never assembled in country and he had to return without leading the first Australian airmen into combat, a distinction that instead went to Petre as commander of the Mesopotamian Half Flight the following year.[2][7]

With Petre on active duty, Harrison took on the main responsibility for providing basic flying training to the pilots of the first three squadrons to be formed in Australia for overseas service. Many of his students would go on to play a prominent role in the future Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), including Bill Anderson, Harry Cobby, Adrian Cole, Frank McNamara, Lawrence Wackett, and Henry Wrigley.[11] Having graduated twenty-four new pilots by the end of 1915, Harrison was able to establish the first AFC squadron, designated No. 67 (Australian) Squadron, Royal Flying Corps; it was however commonly known as No. 1 Squadron AFC from its inception, and officially so from 1 January 1918.[12] The unit departed for Egypt in March 1916 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel E.H. Reynolds.[11] Nos. 3 and 4 Squadrons AFC were formed at Point Cook in late 1916 to operate in France following advanced training in England.[13] In addition to his instructional and administrative duties, Harrison put his mechanical abilities to use initiating the building of aero engines in Australia and maintaining the CFS's complement of airframes; according to Wackett, only Harrison had the skill to keep the obsolescent machines in the air. He was appointed officer-in-charge of CFS in June 1917 with the temporary rank of major; this was made permanent in September 1918.[1][2] The CFS was disbanded at Point Cook on 31 December 1919.[14]

Interbellum and World War II

Harrison began a long association with engineering and air safety when he was posted to Britain for secondment to the Aeronautical Inspection Directorate following the end of World War I.[2] He transferred as a flight lieutenant (honorary squadron leader) to the newly formed Australian Air Force in March 1921, becoming one of its twenty-one founding officers; the prefix "Royal" was added to the service's name in August that year.[15][16] Dissatisfied with his RAAF rank considering his leading position in the pre-war Central Flying School, Harrison appealed for greater seniority. As a result, he was appointed Air Liaison Officer to the Air Ministry in London, with promotion to the substantive rank of squadron leader.[17] Returning to Australia in 1925, he was appointed Assistant Director of Technical Services in 1927, and soon after helped form the RAAF's Air Accident Investigation Committee. The following year he became Director of Aeronautical Inspection, receiving promotion to wing commander on 1 July 1928. Harrison's position took him throughout the country, inspecting equipment and investigating the causes of air crashes. Promoted group captain on 1 January 1935,[1][2] he took charge of the Federal government's resources committee for aircraft, aero engines, and motor transport, one of a number of subcommittees on the Defence Resources Board set up to investigate and report on the readiness of Australian industry to provide munitions for defence in the event of international conflict.[18]

In 1937, Harrison returned to Britain for further study of accident investigation methods, as well as aircraft production. His position as Director of Aeronautical Inspection was civilianised on 12 March 1938, which saw him retired from the RAAF but continuing in his role.[1][19] He was a member of the court of inquiry into the crash on 25 October of the Douglas DC-2 airliner Kyeema, which overshot Essendon airport in low cloud, killing all fourteen passengers and four crew members. The inquiry's report singled out Major Melville Langslow, Finance Member on both the Civil Aviation Board and the RAAF Air Board, for criticism over cost-cutting measures that had held up trials of safety beacons designed for such eventualities. According to Air Force historian Chris Coulthard-Clark, when Langslow was appointed Secretary at the Department of Air in November the following year, he went out of his way to "make life difficult" for Harrison, causing "bitterness and friction within the department", and necessitating the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Vice Marshal Stanley Goble, to take steps to shield the safety inspector from the new Secretary's ire.[19]

Harrison held the position of Director of Aeronautical Inspection throughout World War II, his staff numbering more than 1,200 by 1945.[1] A reorganisation of the directorate in 1940 had permitted qualified civilian engineers to be recruited for work that required increasing technical expertise, without them having to join the Air Force.[20] In July the same year, Harrison proposed the construction of a series of test houses to help decentralise chemical, mechanical and metrological testing of materials used in the manufacture of munitions that previously had to go through either the Munitions Supply Laboratories or the National Standards Laboratory. The result was a major improvement in the speed of testing and, according to the official history of Australia in the war, "a fuller use of the country's scientific and technical manpower".[21] Harrison's daughter Greta joined the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force, and by the end of the war was ranked flight officer.[22]

Legacy

On 5 September 1945, just as the war had ended, Harrison died suddenly of hypertensive cerebrovascular disease at his home in the Melbourne suburb of Brighton; he was survived by his wife and daughter, and cremated.[1][2] The Minister for Air, Arthur Drakeford, commented that "all members of the service, and, indeed, all Australians interested in aviation, must feel his loss as the snapping of one of the last links with the pioneer days of flying".[22] One of the original Deperdussins that Harrison ordered and helped assemble for the Central Flying School in 1914 later went on display at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.[1]

Despite his accomplishments in overseeing the training of every student pilot who served in the Australian Flying Corps during World War I, Eric Harrison received no decorations or other official recognition, prompting Group Captain Mark Lax, at the 1999 RAAF History Conference, to describe him as "perhaps the unluckiest of the entire AFC ... an unsung hero".[23] He was, however, generally considered to be the "Father of the RAAF" until the title eventually settled on Air Marshal Sir Richard Williams. Harrison's early technical expertise, long association with Australian military aviation as a founder member of the AFC and the RAAF, and "more assertive" personality tended to overshadow the contributions of Henry Petre, whom historian Douglas Gillison considered "equally entitled" to such an accolade. Reviewing the contributions of Petre and Harrison in his volume of The Australian Centenary History of Defence in 2001, Alan Stephens concluded that "perhaps any judgement would not only be moot but also gratuitous, as by circumstance and achievement both men properly belong in the pantheon of the RAAF".[5][6]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 McCarthy, "Harrison, Eric (1886–1945)"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stephens; Isaacs, High Fliers, pp.14–15

- 1 2 Molkentin, Fire in the Sky, pp.5–6

- 1 2 Odgers, Air Force Australia, pp.13–14

- 1 2 3 Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, pp.710–711

- 1 2 3 4 Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp.2–4

- 1 2 Wilson, The Brotherhood of Airmen, pp.1–3

- ↑ Eather, Flying Squadrons of the Australian Defence Force, p.8

- ↑ Prendergast, George Michael at Australian Dictionary of Biography Online. Retrieved on 30 October 2009.

- ↑ Cutlack, The Australian Flying Corps, pp.1–3

- 1 2 Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp.5–9

- ↑ Molkentin, Fire in the Sky, pp.23–24

- ↑ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp.9,16

- ↑ Central flying schools at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved on 30 October 2009.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p.34

- ↑ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp.29–31

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp.37–38

- ↑ Mellor, The Role of Science and Industry, p.28

- 1 2 Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp.312–314

- ↑ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, p.95

- ↑ Mellor, The Role of Science and Industry, p.155

- 1 2 "Father of RAAF dies". The Argus. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 7 September 1945. p. 2. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ Sutherland, Command and Leadership, pp.37–38

References

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1991). The Third Brother: The Royal Australian Air Force 1921–39. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-442307-1.

- Cutlack, F.M. (1941) [1923]. The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 (11th edition): Volume VIII – The Australian Flying Corps in the Western and Eastern Theatres of War, 1914–1918. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 220900299.

- Eather, Steve (1995). Flying Squadrons of the Australian Defence Force. Weston Creek, Australian Capital Territory: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 1-875671-15-3.

- Gillison, Douglas (1962). Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume I – Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369.

- McCarthy, John (1983). "Harrison, Eric (1886–1945)". In Serle, Geoffrey. Australian Dictionary of Biography: Volume 9. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN 0-522-84273-9.

- Mellor, D.P. (1958). Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series 4 (Civil) Volume V – The Role of Science and Technology. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 4092792.

- Molkentin, Michael (2010). Fire in the Sky: The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74237-072-1.

- Odgers, George (1996) [1984]. Air Force Australia. Frenchs Forest, New South Wales: National. ISBN 1-86436-081-X.

- Stephens, Alan (2006) [2001]. The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-555541-4.

- Stephens, Alan; Isaacs, Jeff (1996). High Fliers: Leaders of the Royal Australian Air Force. Canberra: Aust. Govt. Pub. Service. ISBN 0-644-45682-5.

- Sutherland, Barry (ed.) (2000). Command and Leadership in War and Peace 1914–1975. Canberra: Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-26537-2.

- Wilson, David (2005). The Brotherhood of Airmen. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-333-0.