Ernest B. Schoedsack

| Ernest B. Schoedsack | |

|---|---|

| Born |

June 8, 1893 Council Bluffs, Iowa, US |

| Died |

December 23, 1979 (aged 86) Los Angeles County, California, US |

| Occupation | Film producer, cinematographer, film director |

| Spouse(s) | Ruth Rose |

Ernest Beaumont Schoedsack (June 8, 1893 – December 23, 1979) was an American motion picture cinematographer, producer, and director.[1][2] He worked on several films with Merian C. Cooper including King Kong and Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness.

Early life

Ernest B. Schoedsack was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa, on June 8, 1893.[3] He ran away from home at age fourteen and worked with road gangs.[4] He went to San Francisco, where he worked as a surveyor.[5] He grew to be 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m), and his friends called him "Shorty."[6]

Film career

Schoedsack began his career in films in 1914 when he became a cameraman for Mack Sennett. He continued working as a cameraman in World War I.[7] He served in the Signal Corps of the United States Army in France in 1916.[8] He also flew in combat missions.[4] After the war, he stayed in Europe furthering his career as a cameraman.[5] His eyesight was severely damaged in World War I, yet he continued to work with films afterwards.[9] In 1920, Schoedsack helped refugees in Poland escape the Polish–Russian Wars. He worked with the American Red Cross. During 1921 and 1922, he also helped refugees from the Greco-Turkish War. He was hired by The New York Times as a cameraman on an expedition around the world.[5]

Chang and early films

Schoedsack began as a co-director with Merian C. Cooper.[2] He first met Cooper in 1918 in Vienna.[4] They both later worked for The New York Times, but decided to make their own films.[6] Their first collaboration was on Grass which was produced in 1925.[2] That same year Schoedsack met screenwriter and former actress Ruth Rose,[5] would later marry her in 1926.[8] They met on an expedition Galapagos Islands where Schoedsack was the cameraman on that trip, and Rose was the official historian.[5]

In 1927, Cooper and Schoedsack produced the film Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness together, which depicts a man's survival in the Northern Siamese jungle. Schoedsack and Cooper spent 18 months in the jungle in order to produce the film and photograph certain scenes.[2] While producing the film, stampeding elephants that are featured in the movie almost ran over Schoedsack and his crew. The risk was worth it, however, and Chang was later nominated Best Picture at the first Academy Awards show.[5] Schoedsack kept a print of a Bengal tiger pouncing with its jaws open in his office. When asked by a reporter about the photo, Schoedsack said that the tiger had sprung and he shot it.[10]

In 1929, the duo worked to create The Four Feathers film. It was the first fiction film that Schoedsack and Cooper collaborated on. It was also one of the last silent films of Hollywood.[5]

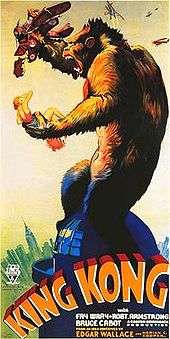

King Kong and early 1930s films

While Schoedsack and Cooper made several other films together, they are most known for directing the 1933 film King Kong.[7] After finishing production on The Most Dangerous Game, Schoedsack joined Cooper in the production of King Kong. Schoedsack focused on scenes with human actors, while Cooper headed the special effects. Schoedsack, Cooper, and Rose inspired the characters of John Driscoll, Carl Denham, and Ann Darrow respectively.[5] The script was co-written by Schoedsack's wife, Rose. This film marked a transition in the working relationship of Schoedsack and Cooper. After the film, Schoedsack only directed films, while Cooper produced them. Their partnership ended, however, in the late 1930s.[7]

In 1932, after filming King Kong, Schoedsack worked on shooting for a film that was never completed called Arabia. For this project, Schoedsack went to shoot on location in Syria.[5] Another film was made in the King Kong franchise. Rose wrote the screenplay for the next film, Son of Kong which was released in 1933 by RKO. Schoedsack was the sole director of the film. Also in 1933, Rose and Schoedsack collaborated on the film Blind Adventure.[5]

Later work

Schoedsack directed several other films in the 1930s including The Last Days of Pompeii, Trouble in Morocco, and Outlaws of the Orient. In 1940, Schoedsack directed Dr. Cyclops which was Hollywood's first science fiction film in technicolor. In 1949 the film Mighty Joe Young was released by RKO and was directed by Schoedsack. It was a reunion film of the main King Kong creative team of Cooper, Schoedsack, and Ruth Rose. This would be the last film that Schoedsack would direct due to eye injuries received in World War II from testing photography equipment.[5]

| Film | Year released | Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| The Lost Empire | 1924 | Director of photography[11] |

| Grass | 1925 | Producer, Director[11] |

| Eagle Squadron | 1924 | Background photographer[11] |

| Greed | 1925 | Director of photography[11] |

| Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness | 1927 | Producer,[12] director[11] |

| Gow, the Head Hunter | 1928 | Director of photography[11] |

| The Four Feathers | 1929 | Film editor, director, director of photography[11] |

| Rango | 1931 | Writer, director, producer in Sumatra, editor, photographer[11] |

| The Most Dangerous Game | 1932 | Director[11] |

| King Kong | 1933 | Director[7] |

| Son of Kong | 1933 | Director[11] |

| Blind Adventure | 1933 | Director[7] |

| The Monkey's Paw | 1933 | Director of prologue[11] |

| Long Lost Father | 1934 | Director[7] |

| The Last Days of Pompeii | 1935 | Director[13] |

| The Lives of a Bengal Lancer | 1935 | Photographer and director of shooting of background location shooting in India[7] |

| Outlaws of the Orient | 1937 | Director[7] |

| Trouble in Morocco | 1937 | Director[7] |

| Dr. Cyclops | 1940 | Director[7] |

| Mighty Joe Young | 1949 | Director[7] |

| This is Cinerama | 1952 | Director[14] |

Later life

Ruth Rose died on Schoedsack's birthday in 1978. Schoedsack died the following year on December 23 in Los Angeles.[9] They are interred together at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles.[15]

References

- ↑ Richards 1973, p. 120-123.

- 1 2 3 4 Hall, Mordaunt (April 30, 1927). "The Screen". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Merian C. Cooper & Ernest B. Schoedsack". They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Aitken, Ian (February 2013). The Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film. Routledge. ISBN 9780415596428.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Ernest B. Schoedsack". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- 1 2 Von Gunde, Kenneth (October 2001). Flights of Fancy: The Great Fantasy Films. McFarland & Company. p. 108. ISBN 9780786412143.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Ernest B. Schdoedsack". Turner Classic Movies. Time Warner Company. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- 1 2 "Schoedsack, Ernest B.". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- 1 2 "Ernest B Schoedsack". Classic Monsters. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ↑ Erb, Cynthia (April 2009). Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood Icon in World Culture. Wayne State University Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780814334300.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Ernest B. Schoedsack: Complete Filmography". TCM. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Now Showing: Chang". Altoona Tribune. May 19, 1928. Retrieved June 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Reddington, John (October 17, 1935). "The Screen: 'Last Days of Pompeii" at the Center Theater". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Retrieved June 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Ernest B. Schoedsack". MUBI. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery". Geni. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

Further reading

- Mario Gerosa, Il cinema di Ernest B. Schoedsack, Il Foglio letterario, Piombino, 2015 ISBN 8876065342

External links

- Ernest B. Schoedsack at the Internet Movie Database

- Ernest Schoedsack at Find a Grave

- Finding aid author: Lucy Brimhall (2013). "Ernest B. Schoedsack sound recordings". Prepared for the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Provo, UT. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- Getting That Monkey Off His Creator's Back article in The New York Times featuring Schoedsack]

- Oakland Tribune Interview with Ernest Schoedsack